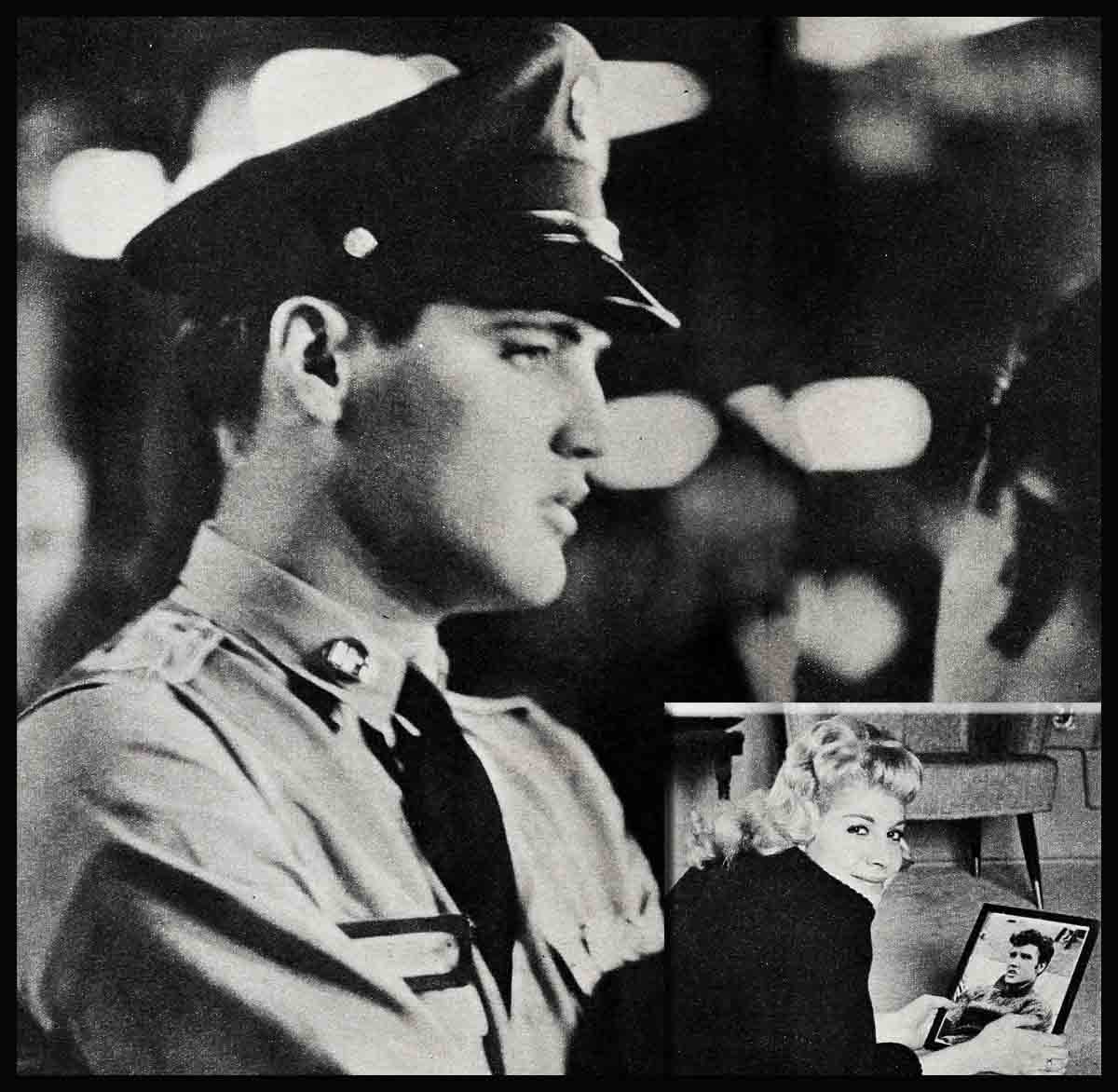

Our Love Song—Elvis Presley

I’m Shari Sheeley and I’m nineteen. I wrote “Poor Little Fool” for Rick Nelson and I’ve written lots of other songs, too. And then I got a message from Elvis Presley in Germany saying that now I’d have to write a song for him, too. Elvis didn’t specify, but I don’t think I could write anything but a love song for him. I guess I’ve been writing it in my mind ever since I first met Elvis the summer of 1956. I was sixteen then, and just going into my junior year at Harbor High School in Newport Beach, a coastal town some forty miles south of Hollywood.

A few months after my sixteenth birthday I got a car and, the day I received my license, I suggested to my sister Jody that we celebrate by taking a ride up to Hollywood (I’d never been there, even though we lived so close). I’d read Elvis was staying at the Hollywood Knickerbocker Hotel while making the movie “Love Me Tender” and I said to Jody, “Let’s go and visit Elvis.” Of course, he didn’t know us and we had no idea how we were going to get in, and that first time we tried we were turned, quite definitely, away. But we managed to make friends with some of the boys who played background for Elvis. and they kept inviting us back to listen to records and talk. And by the end of a week of driving to the hotel each day, we were real good pals with them.

Then one thing led to another, and finally Jody and I got to meet Elvis himself. For some reason, that first time we met, Elvis and I seemed to hit it off quite well, and from then on Jody and I had an open invitation to visit him every time we came to Hollywood. Elvis stayed on right through until October and all that time we must have seen him as often as three times a week. Then every time he came back into town to make a picture he’d let us know. Soon we became part of “the group” that surrounded Elvis.

I remember one Friday night when we all went to see “Pajama Game.” We left the hotel in two cars. When we got to the show, Elvis parked at a gas station across the street. One of the boys went over and bought tickets for everybody. As usual, we had called first to find out what time the show broke. We’d timed it so that we would arrive after the crowd had gone in and the picture had started; that way the theater would be dark. Elvis didn’t like to cause a commotion. Usually our system worked, but that night somebody goofed. We all waited at the gas station, then made a break for the door after we thought the lights had gone down. About two minutes after we got inside, the house lights went on. We were all walking slowly down the aisle, but when the lights went up, Elvis made a fast dive for the nearest seat and landed in a lady’s lap. He apologized, took the one next to her, and slunk way down in his seat. The rest of us scattered all over the theater. It was intermission and while people were out buying popcorn and stuff they played records. The first record that came on was “Don’t Be Cruel.” That was followed by three other Presley records. The manager knew Elvis was there and was trying to be nice, but Elvis got embarrassed. I was sitting way down front, but I could hear a voice in the back calling out, “Ah, lay off that Presley music. C’mon, put on somethin’ else!” It was Elvis heckling his own tunes!

The lights finally went down. But it was too late. The word had spread via the popcorn girl, the ushers, the girl at the box office. Even though the picture had started, it seemed like a big parade was in progress. About three fourths of the audience walked up and down the aisles—all looking for Elvis, while pretending they’d lost their seats. After about a half hour of this, when Elvis realized we couldn’t enjoy the show and neither could the rest of the people, he just stood up. That was our signal. Like soldiers, we all stood up with him and marched out to the lobby. Then we stopped, while Elvis went through his usual ritual—like a scoutmaster checking on his troop—counting, “One, two, three . . .” When he was sure all of our group was together, we made a dash for the cars. We never did* see “Pajama Game.”

When we got outside, it was raining. We drove off, heading back to the hotel. The car radio was on. Suddenly a deejay said, “Here’s Elvis Presley’s latest, ‘Jailhouse Rock.’ ” Elvis put on the brakes, pulled over to the curb, turned up the radio full blast and then, while the rest of us sat in the car, he got out in the middle of the street and started doing the dance routine that went with the “Jailhouse Rock” number in the picture. He was having such a good time! It was lucky the street was deserted. Anybody coming by would have thought a boy standing in the middle of the road, the rain pouring down on him, dancing, was a candidate for a booby hatch—but it was just Elvis’ way. Sometimes he’s like a little boy. When the number was over, he jumped into the car and we zoomed back to the hotel. He was so tickled, like a kid playing in a mud puddle.

There’s one night I’ll never forget. A local TV show had been sponsoring a contest to find a “new Elvis Presley.” The contest had been going on for weeks, and that night they were having the runoffs to pick the winner. The program was called “Rocket to Stardom.” There had been a lot of publicity about it. We all had our hamburgers and Cokes in front of the

TV set, so we could watch the show. There were about a dozen boys—short Presleys,

tall Presleys—all varieties, with three things in common: sideburns, a guitar, and lots of motion.

It was really something, watching Elvis look at other people imitating him. He got a real big kick out of it. About half way through the program a guy strutted out on stage trying to act like Elvis, but he was so extreme, he looked like a peacock. Elvis didn’t like the way he was behaving. When the boy strummed the first few bars of “Don’t Be Cruel,” Elvis stood up, plunked on an imaginary guitar and started singing along with him.

Then he shouted, “Watch it, boy, you’re never goin’ to make that next note, not at the rate you’re goin’.” Sure enough the boy missed the note and Elvis broke up laughing. He ran around the apartment saying, “I told him he wouldn’t hit that note!”

He really enjoyed that show. He picked out one boy as the best. “He sure doesn’t look like me but he’s got a pretty voice. I sure wish he’d find a style of his own, I bet he’d really go places. I think I’ll call him and tell him I think he’s got a great voice.”

Incidentally, Elvis worships talent in people. He’s a big movie and TV fan and is particularly keen about rooting for the underdogs—the ones just starting out. He has hundreds of records I’m sure nobody has heard of. Elvis makes a practice of buying records on little labels that nobody else buys. He always says, “I don’t want those guys to get discouraged, so I keep buyin’ their records. Maybe someday they’ll hit!”

One night we were all sitting around listening to Johnny Mathis records. Then we heard noises coming from Elvis’ bedroom. He went to investigate. He found two little girls and was shocked when they told him they’d climbed up eight floors on the outside fire escape just to see him. We were in the next room, but we could hear him bawling them out.

“Golly,” he said, “why you little baby girls could have fallen and really hurt yourselves, and all on account of me.”

When he brought them in the living room, they were in a trance. They’d finally gotten to see their idol, and there he was bawling them out. But they were so happy they cried with joy, until the tears rolled down their cheeks. But Elvis was pale. He kept looking out the window, straight down to the ground, almost a hundred feet below and shaking his head and saying over and over, “Why I never would have forgiven myself if you’d been hurt on my account.”

Then he asked them if they were hungry. They nodded. He ordered Cokes and hamburgers and sat and talked to them for about an hour. Finally he looked at his watch and said, “It’s too late for you to be out. Now go on home before your mommas are worried to death.”

He walked them to the door. They were just about to leave when one took a package from her handbag and gave it to him.

“Elvis,” she said, “we . . . we want you to have this.” He unwrapped their present. It was a gold mesh expansion belt. He just stood there. He was so touched he didn’t know what to say. Then he gently kissed each of them on the cheek, said thanks, and sent them off home.

He really cares about his fans. When they left, he sat for a few minutes not saying a word. Then he remarked, “Can you imagine those little sweet babies spending their money buying me a gift? Gosh, the kids are wonderful to me!”

I’ve seen Elvis stand for hours in the rain signing autographs and then bawling out the little girls for being away from home so late. That’s why it used to hurt him so much when he’d read things in the paper about him being a bad influence on youngsters and teenagers. It used to practically kill him. “What will my Momma and Daddy think when they read that story?” he would say. His love for his family is something I’ve never seen before. No matter where we were, every night he always put through his call to his folks. He’d excuse himself and go in and talk for a half hour or so. He missed them terribly when he was away from home. When I heard about his mother’s passing away last year, I knew what he was going through—he loved her so.

Every so often Elvis and I would sit over by ourselves and talk about things. At the time I was already a teen-fashions model, but I didn’t particularly enjoy it. I used to tell Elvis that I wanted a career, some kind of work in Hollywood so that I could get my family to move to town. I used to get depressed and tell him I wanted very badly to have a career, to do something creative.

He used to sit and listen to me for hours. He was never too busy to listen and advise me. He had no idea I was interested in getting into songwriting, I didn’t myself at that time, but I’d always loved music and been interested in it. We would sit for hours and he’d tell me about the record business, all the ins and outs. How you go about getting a song recorded, what demonstration records were. We would discuss trends in music, what made a song popular with the kids. And everything he told me I absorbed, never realizing that one day I’d take all of what he said and make it work for me. That’s when he kept repeating over and over, “Shari, you say you want to be an actress. That you’d like to have a career, but that you are afraid and that you don’t know how. Well, honey, all I can tell you is just do what I did. Just have faith in yourself and faith in God and nothing will stop you.”

I used to watch the way he treated so many people with kindness and respect, the way he used to be so grateful to his fans. He used to say, “Shari, I’m only human. When I wait backstage to go on and I hear all that screaming and I know it’s for me, well, sometimes I feel as if my head is going to get real big with all that kind of fuss and stuff. Then I think that my daddy drove a truck and that but for the grace of God I’d be drivin’ one too. Then I say to myself, ‘Elvis, the day you lose your head, then that’s the day when you should go back and start drivin’ a truck.’ You have to have humility, Shari,” he would tell me. “You can never forget

who put you where you are and how many people would like to change places with you.”

Elvis is afraid of very few things, but the fears I remember him having were deep ones. He used to be afraid people wouldn’t like him, especially older people. He kept feeling that they’d judge him by the stories they read, that they wouldn’t give him a chance to show them what he was really like. He used to say, “I love those little girls who are my fans, but I sure am afraid of their folks and the rest of the older people. They just don’t like me.”

He’d purposely avoid going to parties he was invited to because he was afraid people wouldn’t accept him, except as an oddity, as a curiosity. He’s so deeply sensitive that he preferred staying away from places where there was the least chance he would be disliked.

That last trip he made to Hollywood, during the filming of “King Creole,” was very hectic. It was Elvis’ best part to date, his most dramatic role. He wanted desperately to do a good job, but he had lots on his mind. Right after he finished the film, he was to be inducted in the service. He wasn’t afraid of the Army itself, he was only scared about how the other guys would take to him. One night we were all having dinner, and one of the boys still in the group, without meaning to, started talking about some of his experiences in training camp and how rough it was on all the guys. Then he said, “Gosh El, if that’s the way they treated us ordinary GI’s, what will they do to you?” Elvis got pale. I went over to him and he just sat there and finally he looked at me and said, “Shari, do you think they’ll give me a chance? Do you think they’ll get to know me before they make up their minds about me, or will they hate me because I’m Elvis Presley? I sure want to do the best I can to be a good soldier. I just hope to God they let me.”

It was time to say goodbye. That night when Jody and I drove back to Newport we were very quiet. Elvis was going away—for two years.

Two months later, I had “Poor Little Fool” published. By that time Elvis was in Texas at Ft. Hood. But one night the phone rang. It was George Klein (a disc jockey friend of Elvis’). He said, “Shari, I just got through talking to Elvis. He tried to call you but your line has been busy for an hour and he could only hog the phone booth so long. He asked me to call you and tell you he just heard about your song. He said he was so thrilled when he found out you’d written, ‘Poor Little Fool’ that he forgot where he was, and right in the middle of the barracks he started jumping up and down shouting, ‘My friend Shari wrote that song!’ ” George went on telling me what Elvis had said. Naturally I was thrilled. At last it seemed as if I really had a future.

So many things have happened to me since that summer of 1956 when I started out to meet Elvis. All of it has been wonderful, but one of the most wonderful things of all was the night in Nashville, Tennessee, when I received an award for having written “Poor Little Fool.” It had sold over two million records. When the program was over, I heard someone call my name. I turned. It was George, and he’d come all the way from Memphis to see me. We sat and talked. Then George said, “Shari, I talked to Elvis in Germany last night and he gave me a message for you. He said, ‘Tell Shari when I get home I expect her to write a song just for me. Tell her not to forget that I’m counting on a Sheeley song.’ ”

And I’m counting the days until Elvis returns. I’ve got tunes and words running around in my brain, but I still haven’t come up with a song that is just right for Elvis. I have to think of something very special—because he’s a very special person to me.

THE END

—BY SHARI SHEELEY

EL’S LATEST FOR RCA-VICTOR: “I NEED YOUR LOVE TONIGHT,” BACKED BY “A FOOL SUCH AS I.”

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE JUNE 1959