Look Who’s Smiling!—Stewart Granger

One momentous day last summer the “Moonfleet” company was on location and an important scene was being shot of Stewart Granger. The day was momentous not for this reason but because that night Rocky Marciano, heavyweight boxing champion of the world, was scheduled to defend his title against an oddly persistent challenger named Ezzard Charles. The bout was to be televised on closed circuits to theatres only, and Granger had purchased a 70-seat bloc in a nearby house for himself, his wife and members of the movie’s crew.

That was nice of him, yes—and not altogether compatible with a Stewart Granger of a slightly earlier time. But wait a minute. It’s not the whole story.

Time dragged and staggered and fell all over itself that afternoon, and soon it became evident that. while Granger would be free to go, the crew wouldn’t. Even after shooting, they’d have to stay around to strike the set and stow the gear. Tough.

Now Granger’s a red-hot man on matters pugilistic and he’d been looking forward to this fight for a long time. But he declined to press his advantage, which again seemed a trifle out of character when viewed against the backdrop of the man who used to be. Instead, deeply pained by the stunned disappointment of the crewmen, he stayed with them, later hosting a large buffet in his motel suite.

It may be that heaven chose to take a benign view of this deed. The fight was rained out and Granger later did get to see it. But that is several coastal miles beside the point. The point is that three years, two years, maybe even one year ago, Granger would not have done what he did.

His failing would not have been due to the loss of money—he is a generous man—nor selfishness, nor even thoughtlessness. But the whole gesture, which once would have struck him as a somewhat gaudy one, would have represented to him an infringement on what he has termed “integrity of conduct.”

“Everybody likes you,” Granger said one day testily to his long-time friend Deborah Kerr Bartley. “What do you want to be liked for?” Miss Kerr, who also has acknowledged a queasy sensation in Granger’s presence that he is planning to cuff her idly on the backside, replied that she thought it was pleasanter than vice versa.

But Granger, huddling within a protective shell of fierce independence, would have little truck in those days with such notions. Or maybe it wasn’t a protective shell. Maybe, as some of his friends strenuously testify, Granger wanted no reputation that he was “bucking for a merit badge.” Whatever the case, he got what he sought—if he truly sought it.

Granger was not widely liked. He was, in some quarters, rather intensely disliked. And in all quarters, he was intensely respected. The greater hostility he felt, the more belligerent he became.

Indeed the only sensation—if sensation it can be called—that Granger did not arouse was indifference. There were people who liked him, people who didn’t like him and people who didn’t know him.

Yet the respect he inevitably exacted was well-earned. On the Metro lot one day, Granger encountered a bit player who obviously was not enjoying a flush period. The two shook hands briefly, in fact coolly, and when the bit player went his way, he was palming a twenty dollar bill, a little something Granger had left there without a change of expression.

“Now, why,” asked a friend of Granger who had caught the transaction, “did you do that? The guy’s never done a thing for you but put you on the pan. Who’s bucking for a merit badge now?”

“I know, old man,” said Granger. “But there’s freedom of opinion, isn’t there? Furthermore, how does his opinion of me make-him any less hungry? And besides,” he added thoughtfully, “he may have a point there.”

Thus it may be fair to ask at this point, why the change in Granger? Why this mellowing process that has turned him in the last year into an infinitely warmer and less truculent person?

Is he somehow rid of an inferiority complex? Intimates say this is ridiculous because he never had an inferiority complex. Is it the gentle, constant influence of his lovely and talented wife, Jean Simmons? Well, perhaps to an extent, but Jean’s been around all the time. Or did the man read a book? No. Not that kind of book, anyway.

Actually, the best available sources believe that the change in Stewart Granger has come in part from his belated recognition—Granger is forty-one—of the fact no man can stand alone.

Granger has found in the exercise of his profession a peace that was hard come by. In the working out of the task he has set himself, he has found what apparently he wanted from the beginning. But he has discovered at long last that he was not alone, battering at imperfection single-handed.

“You know,” he said recently in a tone of mild and gratified surprise, “we’re all in this thing together. And I couldbe wrong.”

This was quite a yodel from the star who used to go to the mat with producers or directors on the most niggling piece of business he considered wrong for a picture. It didn’t have to be Granger’s piece of business, though Granger in the end was his paramount consideration. It was anything that offended his aesthetic senses.

To a degree, of course, Granger is still like that. Sloppiness in film-making offends him deeply. He has said so and will say so again. But these days, he tends to vent his disagreement in the light of sweet reason and to recognize that others as well have a stake in the proceedings and are as anxious as he to have it right.

Granger in the old era once did battle with a director who finally advised him that he, the director, had been in pictures for twenty years and might conceivably know what he was talking about. “Truly?” said Granger. “May I tell you something? I’ve known an actor who’s been on the British stage for forty years and is still regarded as the lousiest actor in the empire.”

The Granger of 1954 would almost certainly phrase his reply more tactfully. In extremis, he might even keep his mouth shut.

Dealing with Granger in his entire relationship to Hollywood and pictures is not much easier than trying to describe an egg beater to a Zulu, but certain things can be and should be understood.

One is that he has long gagged over the by-products of his profession, and even today can no more than tolerate them. In general, these are autographs, personal appearances, night-clubbing, flamboyant public recognition and—although he submits with grace—certain types of interviews.

“I hold the unpopular minority view,” he once told a writer, “that an actor’s job is done when he’s left the studio. Rationally, I know it’s not so. I’m talking to you, for instance, and not being too much of a ruddy monster, I hope. After all, I knew what it was going to involve when I went into it. But you know, even a player, even a ham, likes to feel he’s off sometimes. Off the stage, out of the public eye. Truly, I feel this. I feel the people might be happier if we kept to ourselves when we’re not working, leashed or in cages like animals in the zoo. Then everyone could have fun guessing what we live like, and the wilder the guesses, the better. You know, I go for this lion-on-a-leash bit, pouring champagne in our hair, and all that. But the trouble is, I don’t do it. I am so damn dull for readers. I wish I could make something up for you. But nothing earth-shaking will come of this, nothing of lasting historic value. We entertain on a limited scale. The Mike Wildings. Liz Taylor, you know. Tony and Deborah. The Nivens. There’s food around. If anyone’s hungry, they can eat here. If not, we don’t shove it at them. Night clubs—no. Lord, I am so ordinary!”

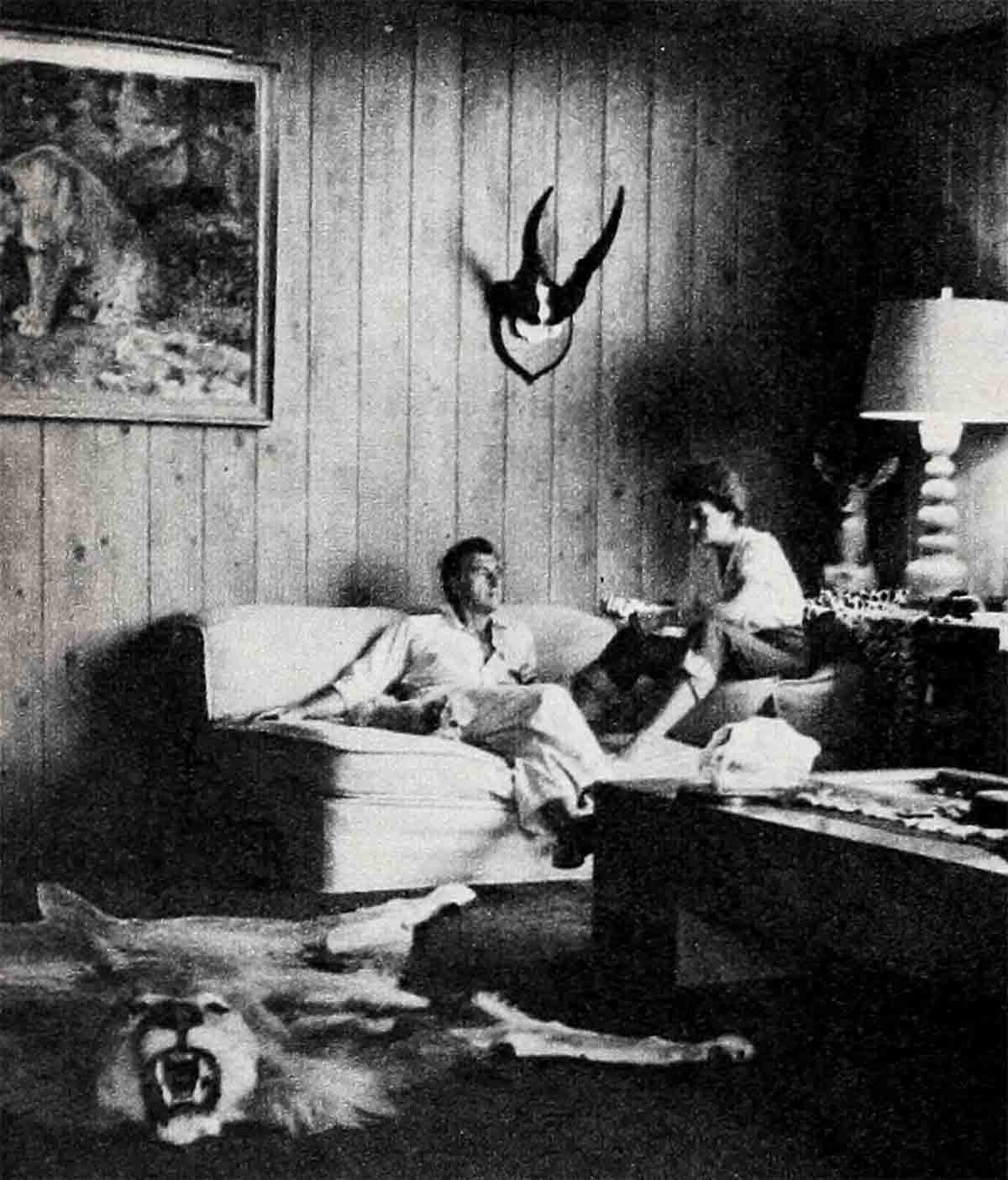

The scene was the Grangers’ dwelling in the hills between Hollywood and the San Fernando Valley. It’s a nice little job with a shake roof, a pool, a dizzying view on all sides and a rather persistent wind. The speech was convincing. But one or two props weakened it. Granger’s audience had one foot on a lion skin. Granger had shot the lion. The ash tray between the two was a converted elephant’s hoof. Granger had sloughed the elephant. He moved a bit carefully to his right on account of an old rib accident. A water buffalo had cracked two of them. Then again, there had been the incident of the night before. After the Bogarts had left.

“Tell him about the tree,” a bystander admonished Granger.

“What tree?”

“You know. Last night.”

“Oh, that tree. You tell him, old man. I’m not going to answer for boring the reading public any more than I have to.”

The Tree, duly corroborated by Granger, went like this. Granger had bought a tree, a birch. Paid seven hundred dollars, including transplanting. The boys had stuck it in the ground. Two days later in the witching hours of the night, the winds had come—with near-hurricane velocity. A peculiar sound awoke Mrs. Granger. It was the tree being un-transplanted. Rapidly, too. She shouted for Mr. G. And while she called for help, Mr. Granger stood locked in mortal combat with his birch, determined to prevent seven hundred dollars from rolling down the hill to destruction. It was an epic struggle. Granger and tree were swept from side to side. If tree went, Granger was going with it—a fall of possibly 3000 feet. When help got there, the combatants were right on the lip of nothing. But the tree was still present and accounted for.

“You see?” said Granger. “Nothing exciting. Now if it had been a mountain lion . . .”

In trying to understand Granger, bear this in mind. He wanted to act—certainly. He was amenable to being an actor, but never did he court celebrity. If in the very beginning he enjoyed fame he has long since ceased to.

“The happiness I’ve got,” he has said, “has been from the work, from the feeling of rightness I’ve sometimes got from it. I can get this feeling in a screening room with only two other people, watching a day’s shooting. But when it’s time for the premiere and the crowds and the lights—then it’s all behind me and my rightful place is home. Do you see what I mean? There must be a dreadful malnutrition of the spirit to have to take nourishment from celebrity. All that, you know—it’s not an ambition, it’s a day-dream. The satisfaction in maturing is in the work, in doing as well as you can the thing you happen to know how to do. The nourishment comes from within, or it doesn’t come. There’s nothing else. And till you know that, you don’t know peace. Forgive me if I sound pompous, but it’s true.”

Granger is in truth a zealous perfectionist. Making “King Solomon’s Mines” in Africa, he declined to speak a Nairobi dialect because the location was two-hundred miles north of Nairobi. He was bitter over being forced to use blanks in firing an elephant gun. “Those things kick your shoulder off. Now it’s not going to buck any harder than a squirrel rifle and I’m going to look like a ruddy fool.” He doesn’t believe in pulling punches in screen fights, and once continued firing a gun that was back-flaming painfully into his face. “It might really have done that, you know. The scene had guts to it.”

All this combines into an admirable craftsman’s quality, but they don’t make Granger easier to work with on a set.

On the other hand, Granger’s facade away from work has thawed immeasurably, and his scope of social activity widened proportionately in the last twelve months. That is why his friends are so sure that the inner peace and confidence he has finally found have been therapeutic measures of enormous value.

Granger still has the remnants of what he describes as “a filthy temper,” but he now has it pretty well under control. It flares on the set from time to time, but not with the old virulence—and with a considered understanding of the rights of others, not to mention their feelings. It still erupts violently over rumors of trouble between him and his wife, but now contempt for talebearers dilutes the rage and diverts it to a healthier channel.

His pride in his own theatrical judgment is stubbornly maintained as ever—but he was able to say not long ago:

“I told Jean right from the beginning she shouldn’t play Ophelia in ‘Hamlet.’ But she wouldn’t listen. Just a youngster, you know. Went right ahead. All right, what’s it done for her? Nothing but make her a star. If she’d paid attention to me, it never would have happened—and I’d have had to give her three free swings at me with a meat cleaver. Ugly prospect, now that I think of it.”

Granger’s honest handle, as you likely know, is Jimmy Stewart. But Jimmy Stewart’s name is Jimmy Stewart, too, so Jimmy Stewart changed his to Stewart Granger to avoid confusion.

Although he comes from theatrical forebears, Granger never thought much about going in for acting himself until he became aware that good-looking girls were part of the environment. That fired his ambition. His parents were more for him being a singer or a doctor, but the latter he declined “because you ought to be three-quarters saint and I’m not even a sixteenth.” As for singing, there was power and resonance to the Granger voice but not too much range.

Granger did pretty well on the British stage before being tapped for pictures and even better with the Black Watch Regiment in World War II before an ulcer put him out of business.

After that, he got real hot in films, was dragooned to Hollywood by no great effort on the part of the local dragooners, became top boxoffice, incurred enemies and made friends—all in something like that order. Now it is widely felt that the “new” Stewart Granger, whatever that may be in the language of psychologists, is the real one and the one here to stay.

Also, it has to be said for Mr. Granger in conclusion that he, like everyone else, has had to make do with the face that was given him, and that while strikingly handsome, it is not the sort of face which exerts instant, overwhelming appeal. His is the kind that grows on you. The lower lip is full and drooping, the nose almost aggressively Barrymoresque, and the whole gives an air of general hauteur. Still and all, don’t stick Granger with it. “Give me back my eyepouches and my wrinkles!” he screamed once at the Metro art gallery after they’d retouched some of his still pictures. “I’ve worked years for them!” That’s a ham talking? It assuredly is not! And in sum, the 1954 model Stewart Granger will look like the old Granger, but it’s what’s behind the facade that bears watching.

THE END

—BY JOHN MAYNARD

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE MAY 1955

vorbelutr ioperbir

17 Temmuz 2023Appreciate it for all your efforts that you have put in this. very interesting information.