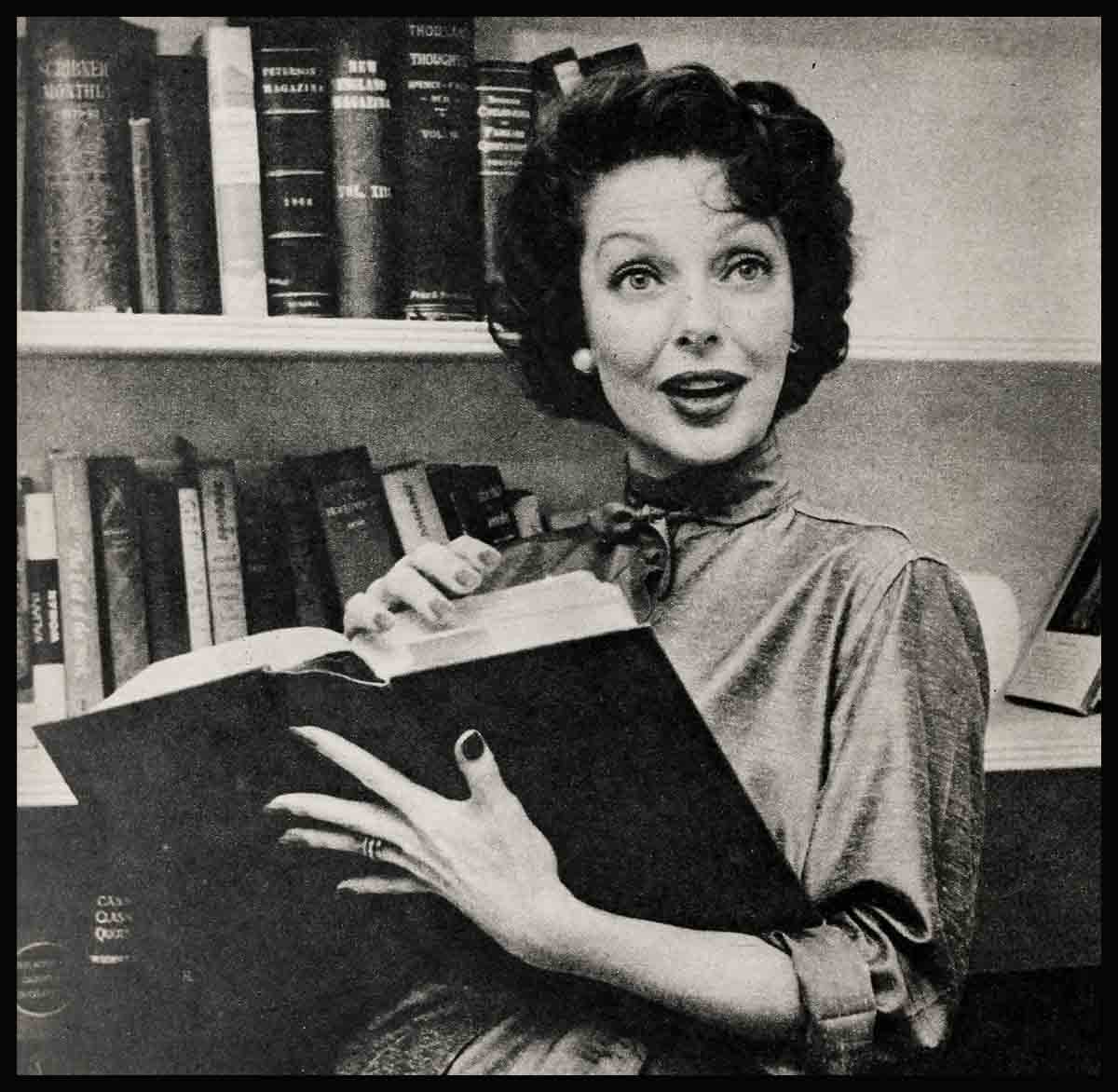

Debbie & Eddie Fight Over Sons Religion!

The lowest point in Eddie Fisher’s life? The one awful moment, among all those hundreds of thousands of miserable moments, when his feet scraped bottom and his heart cried out, “Oh, Lord, why have you forsaken me!”? Some people would say that this moment occurred as he boarded the plane which was to take him away from Rome, away from Elizabeth, away from love. Other people would say that this moment took place when, in the midst of a press conference at which he was reassuring the newsmen (and himself!) that everything was all right back in Italy, that he and Elizabeth were still very much in love, that he was only in the United States on business—right then, almost in the middle of an “everything is all right, honest” kind of sentence, he’d been called to the phone. A long-distance call. From Rome. It was a few minutes later, some people claim, that he touched bottom—the very bottom, as he returned ashen-faced to the conference and his lips mouthed assurances which his eyes denied.

Two moments of misery, two choices, and yet neither, probably, represents Eddie Fisher’s dark night of the soul, his minute of complete and helpless despair. That moment, surprisingly enough, didn’t involve Liz Taylor at all. No, it concerned his children, six-year-old Carrie and four-year-old Todd—especially Todd. And it involved their mother, Debbie Reynolds, Eddie’s ex-wife. Again, the incident featured a phone call; and again, after the call was completed, Eddie was ashen-faced: an expression compounded of grief, frustration and fear. The kind of look a man gets on his face only once or twice in his whole life—times when he hears disturbing news about his only son, for example.

His son—it had been towards Todd, his son, and Carrie, his daughter, that his thoughts had turned immediately after he received his message of rejection from Liz. He’d blurted out to the newsmen in New York, “I gotta see my kids—they gotta see me,” and then he’d flown out to the Coast to be with them. The reunion with his kids—it just had to be perfect. Nothing must go wrong. The kids, Todd and Carrie, what else did a guy have to live for?

So he made his plans carefully, as carefully as a director sets up an important scene in a picture. The setting had to be just right, so he rented a secluded estate in Beverly Hills—where he and the kids could be all alone, with no strangers poking around. A place just for Carrie and Todd and himself, where they could romp around and play and get to know each other all over again. Privacy for love to flourish, for Eddie had learned the hard, hard way that only Ashes can preserve love in a goldfish bowl when the whole world is standing by and peeking in.

The reunion was private and it was perfect. A little girl’s face peering up at his and saying softly, “I love you. Daddy,” and a little boy slipping a tiny hand in his father’s big one and clutching it ever-so-tightly. Then they hugged and kissed and climbed all over him.

That’s the beginning. The ice is broken and now warmth and love envelop the three of them. They play hide-and-seek on the lawn outside the big house. They splash in the pool (so like the pool next to the Villa back in Rome). They lie in the sun: Eddie reads to Carrie, and then Carrie reads to Eddie. Suddenly, Carrie is up on her feet and away like the wind, exploring every nook and cranny of her daddy’s new house. Soon, however, she is back, bringing with her a present for her father—a picture of a flag she drew in school for Flag Day. Now she chatters about school and boy friends and girl friends. Eddie listens and smiles. Todd watches his father watching his sister, and he smiles, too, and his face—at that moment—is the exact image of Eddie’s.

It’s snack time. Lots of bing cherries for Carrie. Lots of fresh pineapple slices for Todd. Milk for all. And lots and lots and lots of love.

Too soon, it’s time to say goodbye. Four chubby arms wrap around Eddie’s neck, and he squeezes Todd and Carrie hard as if he’ll never let them go. But he has to release them; and until the next time they meet he must be content with only a large photograph of Carrie and Todd, on which they carefully printed their names in large letters—a present they had wrapped themselves and given to him on Father’s Day.

Until the next time . . . and miraculously, so it seems to Eddie for whom the past is a bad memory and the future an unfathomable blank, there is a next time, and a next time, and a next time. And it is during one of these “next times,” when he and his children are caught in a sudden light rainstorm, that he talks to both about nature—and about God. It’s not easy for a father to discuss these things with young children, and for Eddie, who had been separated from his son and daughter so long, it was certainly doubly difficult at first. But not for long: Carrie’s responses to what he was saying were amazingly perceptive. Not that he shouldn’t have expected this from his daughter, whom he calls the “Why?” girl because of her curiosity and responsiveness. But Todd, the quiet one, the observer—his reactions to what his father was saying were nothing short of astounding.

At that moment Eddie definitely made a mental note to discuss with Debbie their religious training as soon as possible. And as he watched his young son gazing up at him in awe and wonderment, he must have done something else, too. He must have pictured himself taking Todd to his temple in Hollywood, where the youngster could learn through pictures and stories the ageless lessons of the Old Testament. He must have pictured himself helping his son with his Hebrew lessons. He must have pictured himself teaching his boy the ancient Jewish prayer: “Praised be Thou, O Lord, our God, King of the Universe, who causest my eyes to close in sleep.” He must have pictured himself giving Todd a different present on each of the eight days of Chanukah, the Festival of Lights, when the ceremonial candles always burned brightly. He must have pictured himself presiding at the Passover service—the proudest day of the year—when, in answer to the traditional query, “Wherefore is this night different from all other nights?”—and to the three other questions—Todd, his youngest child, would deliver the age-old replies, recalling the Jews’ exodus from Egypt and their deliverance by Moses from slavery. He must have pictured himself at his son’s Bar Mitzvah ceremony, where the youngster, having reached the age of thirteen, would stand and recite a speech in Hebrew accepting his responsibilities as a man.

The fond dream of a loving father, suddenly interrupted, and yet at the same time made real, as he feels his son’s arms encircle his neck.

The fatal day

So a few days later, when Eddie called Debbie to arrange to have the children visit him, he brought up the matter of religion, with particular reference to Todd. He casually asked Debbie whether she thought Todd was old enough to understand and absorb some of the elementary lessons of Judaism.

Debbie’s answer, delivered in a tone as casual as Eddie’s own, was that she didn’t feel little Todd should be raised in the Jewish faith.

There was a long moment of silence on the phone, a moment in which Eddie touched the very bottom and found out what misery really is. Then, fighting to keep control of his temper yet sounding anything but casual, Eddie reminded Debbie that she’d promised him, promised him three years before, that she would allow Todd to be raised as a Jew—to be raised in his father’s faith. Of course, he’d never asked her to put this promise in writing. She’d given her word—and that was good enough for him. Now she’d changed her mind. Did she have a reason?

Now it was Debbie who was trying her best to remain casual. Ever so politely she reminded her ex-husband “that it was a woman’s privilege to change her mind—hadn’t he learned that by now?”

Eddie, who had controlled his temper when he learned his wife was first secretly—then openly seeing Burton; Eddie, who had controlled his temper at various press conferences—in spite of the jibes and jokes from reporters about Liz’ loving another man; Eddie, who’d controlled his temper when those same reporters printed stories that Liz had kicked him out instead of the truth—that he had left her; Eddie, who’d turned the other cheek so often, had reached the end of the rope. He could control himself no longer. He blew his top—and the words that ensued were as hot and heavy as any Eddie has ever uttered. Debbie remained adamant. She’d changed her mind—and that was all.

When Eddie hung up the phone, his face was the color of a dead ash from which all the fire had long since been burned out. But etched there was grief.

Yet, there was nothing he could do. Debbie had made her decision and nothing he could say or do would change it. Perhaps he might have been able to do something about it back then, three years ago, when he’d split up with Debbie in order to marry Liz. Perhaps if he’d stopped and thought back then, all this that was happening now wouldn’t have had to happen. But he’d been in such a hurry then, so much in love that he’d agreed to anything and everything Debbie had demanded in the divorce agreement. Alimony? Whatever you say! Custody of the children? Whatever you wish. Visiting rights? Whatever you desire. I’ll agree to anything as long as I can have my freedom.

But today things were different. He wanted to see the kids more—not just when the divorce agreement permitted him to, but also when he wanted to. But sometimes when he’d phone and ask to see them, it wasn’t possible. They were off visiting Grandma and Grandpa Reynolds in Burbank, or they were at a party with some of their friends, or they were someplace else. And always, when he’d see them on-schedule or off-schedule (even that first time after eighteen months of separation), they were accompanied by their nurse (this, too, was part of the divorce agreement), and he could never have them completely to himself.

A bit of security

And, more than anything else, he wanted Todd to be raised as a Jew as he himself had been raised as a Jew. It was just that he himself had been a child of divorce; he himself had known how it felt to suddenly be without your own father. One of the things that had kept him going and given him a bit of security was the knowledge that even though his father was no longer there, he could be close to him through his belief and worship of his father’s God. A child separated from his father is bad enough; a child separated from his father’s religion is a sad child.

Debbie, shortly after the divorce had gone through, had said, “I’ve brought Carrie and Todd up to respect and adore Eddie. They will always love him as you love only your own father.” Eddie believed her then, and he believes her now. The joy and warmth the children show towards him are living proof that Debbie has not tried to erase or distort the image of him in their minds. And in other ways, too, he knows that she is a good mother. His children’s naturalness and happiness are proof enough of that.

Sometimes, he even understands what may have led her to change her mind about raising Todd in the Jewish faith. After all, it’s confusing to children if one of them. Carrie, is raised as a Christian, and the other, Todd, is brought up as a Jew. But, and Eddie always comes back to this, a promise is a promise, something basic and sacred in itself.

Besides, you just don’t change faith like you change clothes. Eddie is Jewish, his father was Jewish, his grandfather was Jewish, and so on back through time. His son. in the world’s eyes, is Jewish, no matter what is said or done to try to make it otherwise. But without Jewish training, without the benefits and knowledge that come from an active realization of his Jewish heritage, Todd will be between worlds—a Jew who is assured he isn’t a Jew, a Christian who is really Jewish.

Right now, it seems that Debbie’s plans for Todd’s religious upbringing will pre-vail. Her verbal promise to allow Eddie to take charge of their son’s religious training is not legal, and, therefore, not binding.

What can Eddie do?

Eddie can only wait. He can only wait and pray that Debbie will come to understand all his heartfelt reasons for wanting his faith to be Todd’s faith. Eddie has some things in his favor. There is the fact that Todd is still young. Because of this, time can be his staunch ally. Perhaps in time Debbie will watch his relationship with his son grow. Perhaps she will realize that Eddie’s wishes are motivated by one thing and one thing only—love! Love of his son and love of his God. Maybe then, Debbie will use her womanly privilege again—and change her mind.

—BY FLOYELLA SPENCER

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE SEPTEMBER 1962

zoritoler imol

31 Temmuz 2023Its great as your other articles : D, thankyou for putting up.