Will Jerry Lewis Be A Good Mother?

Patti Lewis was already in bed when Jerry came bounding into their New York hotel apartment that Saturday night last winter. “Honey,” Jerry said, “I was great tonight, great.” He gave a couple of loud, happy yawns—one for the matinée he’d done that afternoon, one for the night show. Then, never one to waste time wasting time, he began ripping off his clothes. “I was on stage for seventy-seven minutes!” he said, telling about his show at THE PALACE, “and the people—a $6.60 crowd!—got up on their feet and they yelled themselves hoarse just to let me know how much they liked me.”

Patti smiled, “That’s wonderful, Jer.”

“Seventy-seven minutes,” Jerry repeated as he raced into the bathroom to brush his teeth and throw some water on his face.

He was in bed a few minutes later. He was still talking about his show that night and Patti took his hand and rolled over a little so she could watch him. She purposely left on the light for a little while because she liked to watch Jerry when he was feeling so happy about something. Besides, she was going to do some talking of her own in a little while and she wanted to make sure she saw the full reaction when she did.

“It was probably one of the greatest shows of my life,” Jerry was saying as he lay there, his hand in Patti’s, staring up at the ceiling, grinning proudly. “Some of the critics belted me a little on opening night, but I was nervous. Sure I was nervous, opening at THE PALACE. But the next night it started going better and we’ve been sold out for every performance and tonight, tonight . . . Patti, I honestly think I’m going to die I’m so happy.”

Patti squeezed his hand. “Jerry,” she said.

“Yeah?” Jerry answered, a little vaguely, as if he were far away, in the wings of a theater waiting to go on, maybe, or on a tremendous stage facing a couple of thousand applauding, cheering people. “Yeah?”

“Jerry,” Patti said, “I wish you wouldn’t die just yet. Because you have me to consider . . .”

“Yeah?”

“And there’s Scotty and Gary and Ronnie . . .” Patti went on.

“Sure,” Jerry said.

“And, after all,” Patti said, “a new baby, a brand new baby, needs a daddy, doesn’t he?”

Jerry nodded. “Yeah,” he said, “sure a brand new baby needs . . .” He let go of Patti’s hand. “Needs a what?” he said, softly. Then he screamed it. “Needs a what?” Jerry turned his head for a look at Patti. After that scream, he figured she’d probably be looking at him like he was crazy—or like a wife looks at her husband when she’s telling him about something beautiful.

And then he hugged her and kissed her, and hugged and kissed her again. And, as he tells it, “I didn’t know what else to do, so I began to cry. Then Patti began to cry. And the two of us lay there for a couple of minutes bawling like a couple of kids. And then I jumped out of bed and I said to Patti, ‘Stay there, don’t go away!’—like she was planning to take a quick walk over to Central Park or someplace—and I ran into the kitchen and filled a water glass with Scotch. I took a sip. I remember it was only a sip because the next morning a maid from the hotel shook her head and said, ‘Somebody’s sure been wasting a lot of good liquor in this place, pouring it into glasses like that and leaving it.’ Then I rushed back and I kissed Patti again, over and over, and then for an hour, or two hours, the two of us were talking, just talking . . .

That certain feeling

“When will it be, Patti?” Jerry asked.

“I guess around October,” Patti said.

“And it’s going to be a girl?”

“I don’t know,” Patti said.

“I think it’s going to be a girl,” Jerry said, with much certainty in his voice.

“We’ll see,” Patti said.

“You know what we’re going to call her?”

“What?” asked Patti.

“Maria,” Jerry said.

Patti smiled. Maria was her mother’s name. Her mother had passed away three years earlier. “That’s nice, Jerry,” Patti said. “Mama would have liked that a lot.”

“Maria Lewis,” Jerry whispered, trying out the name. He nodded. It sounded good.

“And if it’s a boy?” Patti asked.

“Maybe,” Jerry said, laughing, “maybe this one we can call Cary—with a C.”

Patti laughed, too. He was talking about the trouble they had naming their first son. “He’s eleven-and-a-half years old now,” Patti told us recently, “and when we got him we decided—or I guess I decided—to call him Cary after my favorite movie actor, Cary Grant. Well, Jerry wasn’t too happy about the name and, really, it didn’t seem to fit the baby too well and one night Jerry said to me, ‘You know, when he gets big they’re gonna think he’s a girl with a name like that.’ So I said, ‘All right, we’ll make it a G instead of a C.’ And so he became Gary.”

“Ronnie’s a nice name, but we’ve used that one up,” Jerry said now, referring to the name they’d given their second son, now seven years old.

“And we’ve got a Scotty,” Patti said, referring to their fourteen-month-old Scott Anthony, named after Patti’s Patron Saint, St. Anthony.

They both thought out loud for a while, running through the alphabet of names from Archibald to Zeke. And then Jerry shrugged.

“Aw, Patti,” he said, “what are we wasting time for? It’ll be a girl, anyway.”

“That’s what you said last time,” Patti reminded him, “—going out like that months before time and buying all those pink clothes and blankets and stuff.”

“That was last time,” Jerry said. “But this time, no kidding, I have the feeling.” He patted his stomach. “Right here.”

Patti began to laugh again. “Oh, no!”

“No what?” Jerry asked.

“You’re not.” Patti started to say. but she couldn’t go on, she was laughing so hard now.

“The—what did that doctor call it—the high-premium pregnancy?” Jerry asked, trying to hide his smile and act very serious about the whole thing. “Well . . .” he said, thinking it over.

“A high-premium pregnancy,” according to Patti, “is when the father-to-be reacts almost exactly the way the mother-to-be does. He gains weight—Jerry put on twenty-one pounds while I was carrying Scotty. He gets cravings—I don’t know which of the two of us had more of them or ate the stranger foods. He gets very sensitive if he’s ignored the least little bit—I used to have to call Jerry at the studio during the day to find out how he was feeling. And, in Jerry’s case, it got so extreme that he even insisted on being present in the delivery room the night I had the baby. ‘I’ve been carrying it around for nine months, too!’ he told the doctor.”

“Well,” Jerry said now, “I tell you, Patti. I don’t think I’m gonna have to go through any bit like that this time. Because the high-premium jobs usually happen when there’s a lot of tension about whether or not you’re ever going to have a baby; when you’re working very hard and you’ve got all kinds of stresses on you.”

“And,” Patti asked, “you’re not working hard now? No stresses you’ve got? . . . THE PALACE? The pictures you’re going to make? The TV shows?”

“Well,” Jerry said, “it’s all less now.”

“Uh-huh,” Patti said.

“Yeah,” Jerry said, “it’s a lot less now.” He sounded a little groggy, as if he were falling asleep. “And I don’t think,” he said, “it’ll be like it was with Scotty. . . .”

Patti looked over at him. His eyes were closed. She reached to turn off the light. Then she lay back and put her arm on Jerry’s and smiled. She was thinking about her last pregnancy, not too long ago. About those months of carrying her little baby inside of her. About, those months of taking care of her big baby, Jerry.

“Please take care of my wife”

She remembered lots of little things.

“Like,” in Patti’s words, “how he always used to kiss me when he’d come home from someplace and say, ‘How’s the maker of my little pup?’ And like he’d suddenly treat me as if I were made of glass and be afraid when I wore high-heeled shoes and tell me, ‘I don’t ever want you opening any doors and straining yourself’ and get all upset when I would tell him, ‘But Jerry, how am I going to get around the house if I don’t open any doors?’ And how lonely he’d get when he had to be on tour or do a show out of town and would buy a puppy dog to keep him company and then bring it home with him until one day I look an inventory and counted seven dogs around the house and made him promise that the next time he was away and lonely he’d send for one of the dogs—which, believe me, he did. And like when he was away on these trips, some of them lasting for only a few days, he’d call up long distance a couple of times a day and ask about me and how I was feeling and all about the boys and I’d have to tell him exactly what Gary—who’s the other comedian in our family—did that day that was funny, usually a very good imitation of his daddy or Elvis Presley, and if Ronnie was still sitting in the back yard with his pencil and paper inventing rockets and all the other things he’s always inventing. And like how when Jerry was tired at night we’d go to bed early and he’d lie there or a while eating his jelly beans and chocolates—I’ve always got to keep jelly beans and chocolates around the house for him—and sometimes I’d get a slight pain and Jerry would get all upset and even though he’s Jewish he’d put his hands together and pray to my Catholic Saint and say “Tony—that’s what he always calls St. Anthony when he prays to him—‘Tony, please take care of my little wife down here next to me and make her have a healthy baby, please, and we’ll appreciate it very much, the both of us.’ ”

“I’ve got a craving”

Patti turned now for a last look at Jerry before closing her eyes too, and going to sleep. She moved her head and kissed his arm. “Good night,” she whispered.

“Honey?” Jerry whispered back.

Patti’s eyes popped open. “You’re still awake, Jer?” she asked.

“I can’t seem to fall asleep,” Jerry said. I feel kind of funny, matter of fact.”

“You have a headache?” Patti asked.

“No,” Jerry said.

“Your stomach bothering you?”

“No,” Jerry said. Suddenly, he sat up.

“What’s the matter, Jer?” Patti asked.

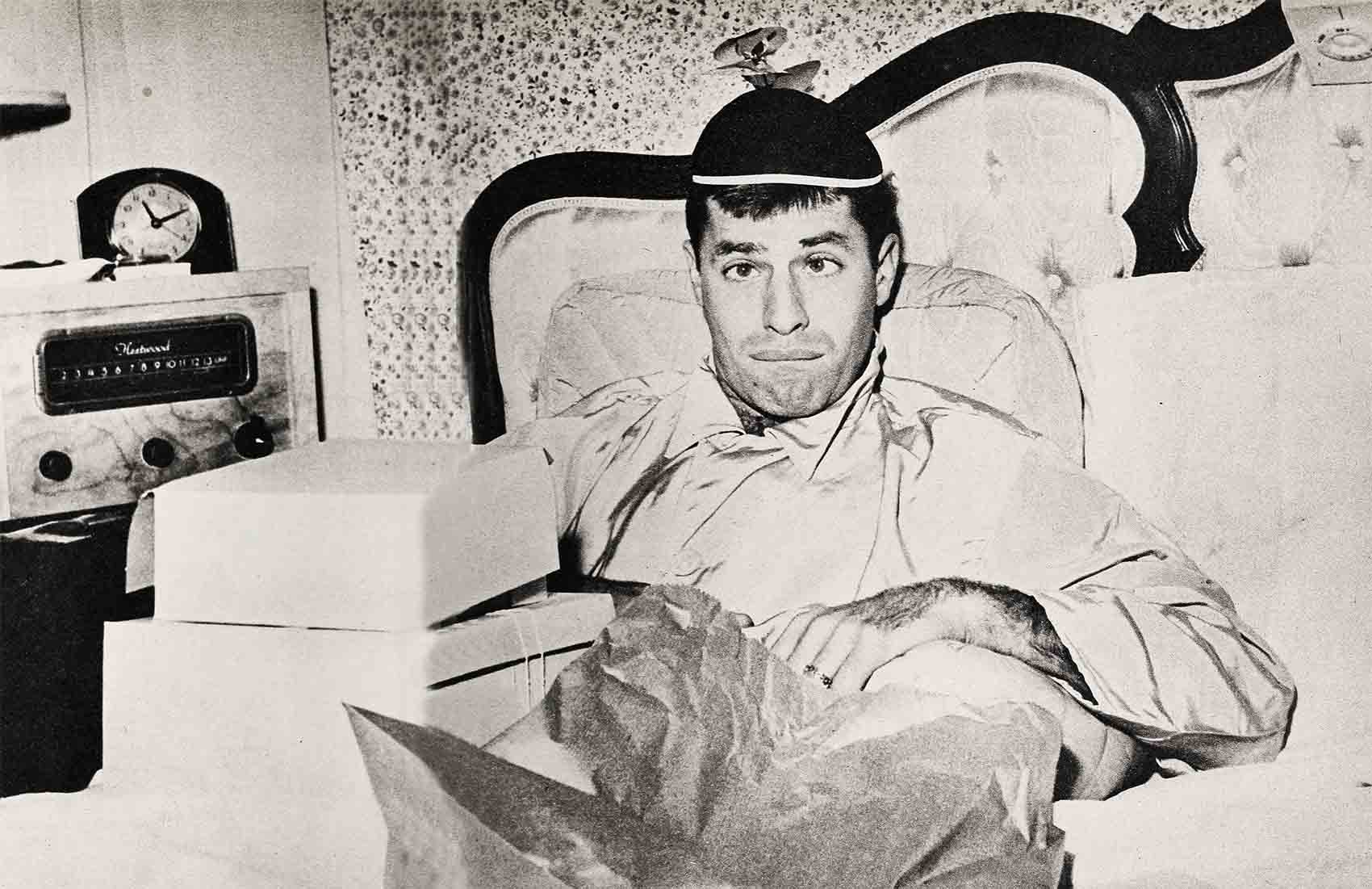

“It just came over me,” Jerry said, his face lighting up. “I’ve . . . I’ve got a craving!”

“Jer-ry,” Patti called out.

“Honest,” Jerry said. “I think I’m going through that high-premium bit again.”

“Jerry,” Patti said, “not this soon.” Jerry jumped out of bed and began putting his clothes back on. “I think there’s a delicatessen over on Lexington Avenue that stays open all night,” he said. “I’m gonna go get you-know-what for me . . . and, Patti, you want the same thing you used to have with Scotty?”

Patti gave up, then and there. “All right,” she said, smiling. “I’ll have the same.”

The delicatessen man who waited on Jerry that am. greeted him with a big smile, but his face turned near-green when he heard the order. “You are sure, Mr. Lewis, that this is not a joke like in the movies you are in?” he asked.

“No,” Jerry assured him, “it’s no joke. My wife is going to have a baby!”

“Oh,” the delicatessen man said, nodding but not quite understanding.

Jerry was back at the hotel a little while later, a small grocery bag in his hand. “Now I want you to stay in bed till I get everything set in the kitchen,” he told Patti. “I don’t want you getting up and staining yourself till it’s time to eat.”

It took Jerry about five minutes to prepare the feast. Then, rushing back into the bedroom, he helped Patti out of bed and took her arm and led her into the kitchen.

“I’m not disabled yet,” Patti smiled, as Jerry leaned forward to open the door.

Jerry turned to see Patti’s expression as she looked over at the table. He was as happy as a Yankee batboy when he saw her smile.

“Oh, Jerry,” Patti said, suddenly feeling close to tears again, despite her smile. She pointed to her place at the table. “You remembered everything. The sauerkraut juice and the two Baby Ruths for me. . . .” “. . . And the baked beans and sour cream for me,” Jerry said, pointing to his place.

They sat down. Just before they began to eat, Jerry looked up towards Heaven, winked and said, “Tony, I guess you knew all this before we did. But Patti’s going to have another baby, just in case you don’t know, and we’d appreciate it if you’d take good care of her, like last time.”

Then he picked up his spoon and Patti picked up her glass.

“Here we go again,” said Jerry, happily.

“Here we go again,” said Patti, staring at her husband and smiling and forgetting about her sauerkraut juice for just a little while.

THE END

—BY ED DE BLASIO

Watch for Jerry in Paramount’s THE SAD SACK.

It is a quote. MODERN SCREEN MAGAZINE OCTOBER 1957