When Oreste Sings, Oreste Sends!—Oreste Kirkop

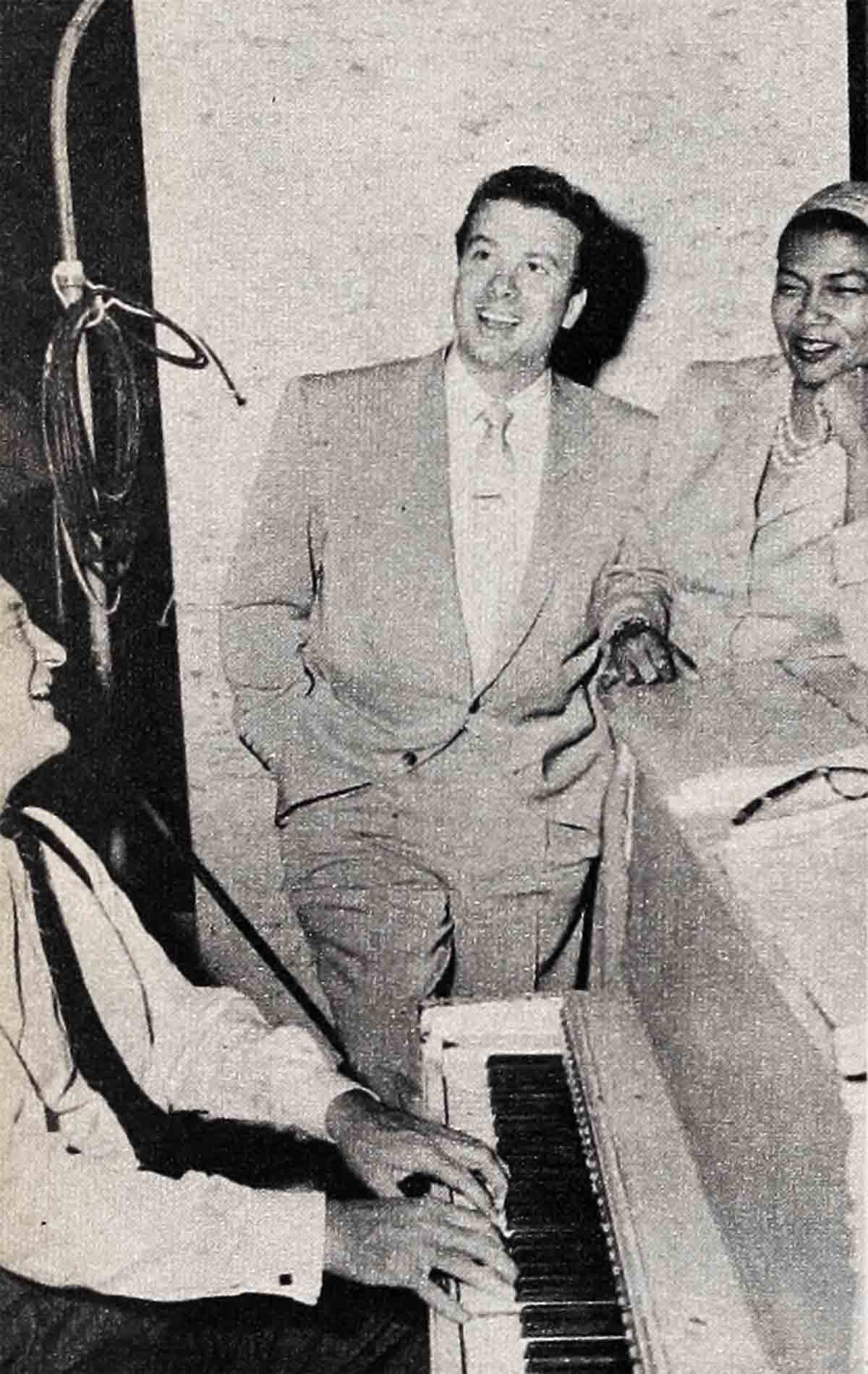

On the set of Paramount’s big musical, “The Vagabond King,” handsome new singing star Oreste, in the lead role of swashbuckling Francois Villon, was saying a last farewell to his sweetheart, played by Rita Moreno. Even with the pallor of death on her cheeks she was still beautiful, still alluring. Kneeling beside her, Oreste bent over and kissed her tenderly on the lips. The kiss lingered on and on.

“Cut!” yelled director Mike Curtiz. “Oreste, what do you think you’re doing? You’re not supposed to kiss her like that!”

“What do you mean, like that?” Oreste parried. “It says in the script, ‘Kiss her.’ So I kiss her. And when I kiss, Mr. Curtiz, I kiss.”

Inasmuch as lovely Rita Moreno was the object of his affections, Oreste’s enthusiasm was understandable. Then, too, this was his first day on the set of his first movie and he first screen kiss of his career. As an opera star in Italy and England, Oreste had always been proud of the recognition he’d won for his realistic acting. It hadn’t occurred to him that the camera might make “realism” a little too intimate.

However, the revelation that a screen embrace was supposed to be different from the genuine article hardly lessened his natural exuberance. A. native of the sun-drenched Mediterranean island of Malta, Oreste (his full name is Oreste Kirkop) has the light-hearted temperament, the ready laughter, the gaiety, fire and enthusiasm so frequently found among the people of southern climes. In his case, this natural bent is reinforced by glowing health, good looks, satisfaction with his career, and confidence based on solid talent. His zest for life expresses itself in a remarkable ability to give his all to anything he does: when he kisses, he kisses; when he works, he works; when he plays, he plays; and when he sings—well, when he sings, he really sings.

Oreste is five-feet ten, weighs 175 pounds, has curly brown hair, gleaming white teeth, a brilliant smile and a forty-five-inch chest. But you can close your eyes, forget the appearance, and still become completely enraptured just listening to him sing. At 29, Oreste has already been acclaimed one of the great tenor voices of our era. His voice is rich, full-bodied, golden, of remarkable range and unerring pitch. It brought him operatic fame in Rome, Milan, and, most of all, in London before Paramount signed him to star in Rudolf Friml’s “The Vagabond King.” His voice would be enough, even if he were short, fat, and bald.

The appearance helps, of course. London bobby-soxers used to line up at the stage door waiting for him, causing the dignified management of staid old Covent Garden Opera House to smile with pleasure. “They were pleased,” says Oreste modestly, “because I seemed to help awaken the younger generation’s interest in opera.” Paramount certainly wasn’t unmindful of this when they whisked him to Hollywood.

Oreste has been in this country for two years, and he is in the unusual position of being a complete unknown to the American public, yet faced with the certainty of fame as soon as his first picture is released in June. As a friend recently said to him, as he was strolling through an amusement park, unrecognized and unnoticed, “You’d better enjoy this while you can, Oreste. A few months from now you’ll have to fight your way through crowds.”

In one form or another, Oreste has been singing for his own or others’ entertainment as long as he can remember. At first, however, the pleasure was mostly his own. “I used to disconnect the loudspeaker of our old-fashioned gramophone, stand on the roof of our house and sing ‘Valencia’ through it,” he recalls. “I don’t think I was much over four or five at the time. ‘Valencia’ and ‘Sera Fina’ were my favorites. Later, I added ‘Rio Rita.’ That was the first movie my dad took me to see. It made a deep and lasting impression on me. Although we had a stack of Caruso records, I didn’t become interested in opera till later on.”

Oreste’s early love of song wasn’t remarkable because, he says, “Everybody sings all the time in Malta. People over here are so quiet by comparison. And there certainly was plenty of noise in our own home.”

Malta or Hollywood, there’d be no reason to question this statement, since Oreste is one of a family of ten lively, lusty children, five boys and five girls. All of the boys showed an early flair for music. Oreste’s four younger brothers are also professional musicians and are members of Malta’s most popular jazz band, Frank Kirkop and his Hot Tuners.

The Kirkop boys are first generation musicians, however. Their father, Jean Kirkop, who died in 1947, was an importer-distributor of naval supplies and British automobiles and his business kept him away from home much of the time. He was a gentle and affectionate man who gladly left the disciplinary chores to his wife. “He loved to play with us, help us build castles and encampments in our garden, and take us places,” Oreste recalls. “We always hated to see him go away on a trip, and were very happy when he came back.” Though he was of French extraction, Mr. Kirkop was blond and blue-eyed, indicating his family’s former Scandinavian origins, apparent also in his name. By contrast, Mrs. Kirkop, the former Netta Panzavecchia, is a native of Malta, dark-haired and dark-complexioned, of pure Italian ancestry. Oreste is a blond type like his father, with green eyes and light-brown hair. He is a Britisher by birth, although English is not his native tongue and he speaks it with a slight accent.

The Kirkop home in Hamrun, Malta, was large and well-built, with many rooms on many levels, winding stairs, vaulted ceilings, tiled floors and white-washed stone walls. The family also had a summer home at Valetta, near the edge of the Mediterranean. With her ten children, Oreste’s mother had a busy life, indeed. “My mother is very much a woman of the old school,” says Oreste fondly. “She has all the traditional virtues. Though she had help, my mother never delegated the responsibility of running her household to anybody. The kitchen was her special domain. She rarely had a chance to sit down to a proper meal herself, though. When she got through serving first helpings at one end of the table, she usually had to start on seconds at the other.” Mrs. Kirkop still lives on Malta with eight of her children (one daughter, Melita, lives with Oreste in Hollywood), and still manages to keep busy looking after her flock of grandchildren—twenty-two at last count.

Although younger than four of his sisters, Oreste is the oldest of the five Kirkop boys and, as a youngster, he was their undisputed leader—especially in mischief. “Whenever my oldest sister, Juza, was left in charge of the family,” Oreste recalls, “she always asked my mother or my dad to take me with them. She figured with me out of the way she had a reasonable chance of controlling the rest of the gang.”

One of the more dangerous activities Oreste organized was rock-fighting between rival teams, as a result of which his handsome face still bears some slight scars. On the constructive side, and quite as popular, was Oreste’s early leaning toward theatricals. “We loved putting on shows,” he reminisces. “We built our own stage, painted our own scenery, wrote our own scripts, and charged the other kids marbles or halfpennies for admission. Everybody always died at the end of the plays. I remember once I was the lone survivor about to commit suicide on a stage littered with corpses. As I looked around for a place to fall, my littlest brother, one of the ‘corpses,’ suddenly jumped up squealing please not to fall on him. It rather spoiled the tragic mood,” he grins.

Other activities during those carefree young years included spearfishing and swimming in the clear, tideless waters of the Mediterranean, climbing countless trees and exploring the small island from one end to the other. Oreste was a good student, attending first a private Catholic school and then Flores College. Growing up under these ideal circumstances, he spent a wonderful, happy youth. But these untroubled days came to an abrupt end when Oreste was fourteen and war broke out in Europe.

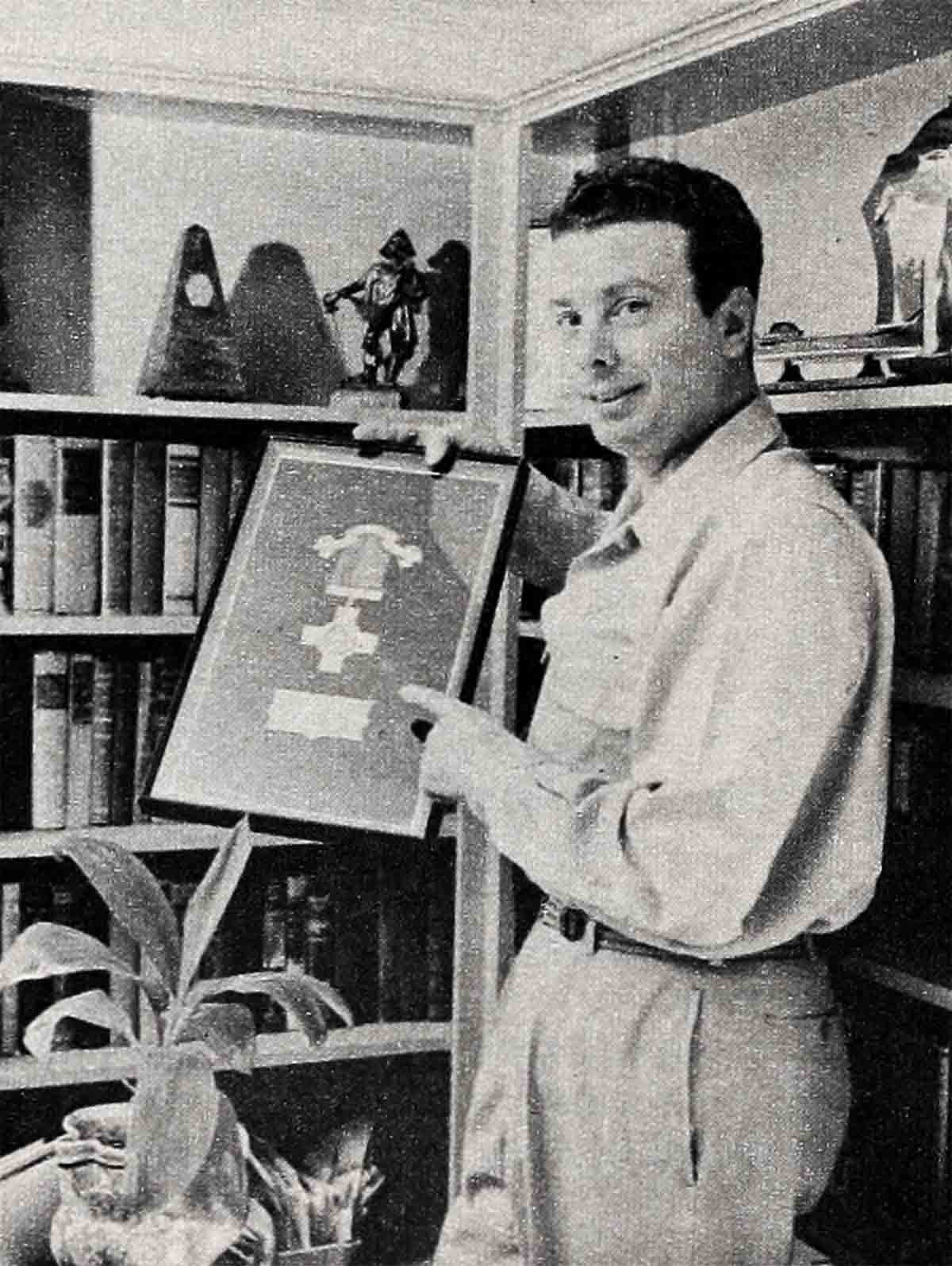

A British stronghold of great strategic importance, the tiny island of Malta became the target of heavy daily bombing raids by Nazis and Italians alike. This lasted for two and a half years, giving Malta the distinction of being the most thoroughly bombed area of World War II and worthy of the coveted Victoria Cross for bravery and resistance against the enemy. Fortunately, the entire Kirkop family came through these bombings unscathed, though Oreste once had a close call in a movie theatre when a bomb struck, killing over two hundred people. The Kirkop home was hit three times and became uninhabitable, like most of Malta’s dwellings. Before long, the vast majority of the Maltese, including the Kirkop clan, were forced to take up permanent residence in the many limestone caves which honeycomb the island and which were dug by the Turks a good many centuries ago.

“It was a pretty dreary existence,” Oreste recalls. “Enough to get most everybody good and rattled, even though we Maltese are generally a pretty easy-going bunch of people. The women used to dash out of the caves between raids to cook their families’ meals in the open, then hurry back into the shelter when the alert sounded again. It got so you didn’t even stop chewing, walking back to the cave with your plate. But spending so much time in the crowded caves was depressing, and everybody was jittery. When I formed a band with two of my brothers, we did it in order to boost our own morale as much as that of our neighbors.”

Backed by his brothers on the mouthorgan and the accordion, Oreste sang for hours on end. Though untrained and untutored, his voice already had great charm and natural beauty. With the bombs crashing all around them, the Kirkop boys went from cave dwelling to cave dwelling, cheerfully trying to make themselves heard above the din. They were loud enough to succeed, and good enough to—immensely popular throughout the island.

One result of this popularity was that it brought Oreste to the attention of a local tenor by the name of Balldachino, who tutored the boy free of charge for a year. After that, shortly before the end of the war, Oreste made his debut in “Cavalleria Rusticana” with the Malta Amateur Opera Company. “I didn’t have enough sense to be nervous or have stage fright,” he recalls. “I just stood on the stage and sang. It was wonderful. The applause was, too. I knew then that this was what I wanted to do.”

Not long after, Oreste made his bow as a professional when he was invited by a visiting Italian opera company to repeat his performance in “Cavalleria.” He sang several other leading parts during the company’s stay in Malta and, at the end of their engagement, was asked to return to Italy with them.

Still far from being a finished performer, Oreste continued to study hard in Rome and Milan during the next few years, making his living from occasional opera and concert engagements in the Italian provinces. He’d left Malta with about three hundred dollars he’d managed to save and never took another cent from home. Frequently, however, his reserves dwindled to a dangerously low point. “I’d often pay for my room and board with very nearly the last of my money,” he recalls, “telling my landlady to rent my room if I didn’t find work before the date to which I was paid up. However, I was always lucky and got something at the last minute.”

Although he never was well-heeled in those days, he had his moments of glory on evenings when his teacher, who was associated with the Rome Opera House, gave him free tickets. “They were usually the most expensive seats in the house,” Oreste says. “The cheap ones were all sold out. Promenading among high society during intermissions, dressed in my tux, with a pretty girl on my arm, nursing an orangeade, I was really living it up.”

But he also had frequent spells of homesickness, especially after his first season in Rome. He couldn’t wait to get back to his family in Malta, wanting never to leave there again. After a while, however, ambition and restlessness got the better of him once more and he returned to Italy to continue his studies. But, since Malta is only sixty miles from the mainland, he always managed to return frequently for visits with his family. Oreste is deeply devoted to all of them. When his engagements took him, first to England and later to this country, he asked his unmarried sister, Melita, to come live with him. Both of them now dream of bringing the entire family over here. They keep in touch with each other by means of tape recordings, with the ones from Malta usually carrying the voices of all their dear ones, their mother, brothers, sisters, nieces and nephews. Christmas shopping for this clan of forty-odd is always a major production, beginning in October and ending with no bank balance.

It was, incidentally, during Oreste’s Christmas visit to Malta in 1949 that he got his first big, professional break. “It’s something I’ve rarely told anybody,” he says, “because it just doesn’t sound believable, though it actually happened.” He was attending a performance of “Rigoletto” at the Malta Opera House when, during the first act, the leading tenor’s voice cracked. It soon became obvious that the tenor wouldn’t be able to go on after the intermission. Right after the first-act curtain, the company’s manager, spotting Oreste in the audience, approached him and asked if he would and could go on in the star’s place. Oreste hadn’t looked at the score of “Rigoletto” in several months but, with characteristic self-confidence, was willing to take a chance on his memory. Moreover, it was a challenge which appealed to him. He quickly agreed, changed into his ailing colleague’s costume, then retired to the back-stage restroom. (This came as a shock to the manager who thought Oreste was having a bad case of the jitters. He was reassured, however, when he heard Oreste practicing his scales in his retreat.)

With only this brief warm-up, Oreste then proceeded to sing the rest of “Rigoletto,” including one long aria in the third act which is so difficult it is frequently omitted. Receiving stormy applause and glowing notices for his magnificent, impromptu performance, he was promptly signed to fill out the remainder of the engagement at considerably more money than he’d ever been paid before. More important, however, was the fact that this was the turning point of his career. It marked the end of his struggling years; he’d made a name for himself.

After some more engagements in Italy, Oreste came to the attention of the Carl Rose Opera, England’s oldest company, and was signed for a season’s engagement throughout Britain, opening at the Grand Theatre in Leeds with another brilliant performance of “Rigoletto,” this time in English. The following season he made his big jump to the Sadlers Wells Company in London. Then, a year later, he rose to even greater heights when he joined the Royal Opera House of Covent Garden, one of the world’s great musical shrines. In addition, he gave many successful recitals at such places as London’s huge Albert Hall.

When Paramount began searching for a new personality for the title part in “The Vagabond King,” Oreste—whose strong appeal to the ladies had been noticed by the studio’s London representative, Richard Maeland—appeared to be a logical choice. He was given a screen test, with the full London Philharmonic Orchestra providing the musical background. It was one of the most impressive and expensive tests ever given. On the strength of it, Oreste was signed to a contract and arrived in Hollywood early in the spring of 1954.

Now comfortably settled in a rented Hollywood duplex, Oreste happily says, “I fell in love with America, and especially California, as soon as I arrived. I like it here. The American people are warm, friendly and generous. It’s so to make friends here. And I particularly—like the sense of equality every American seems to share with everyone else. Back in Malta, it took a war, bombings, and living together in crowded caves for people to forget their class differences. It’s probably the one good thing that came out of all the fighting.”

Something else that has impressed Oreste is—believe it or not—the high degree of discipline he finds among American automobile drivers. “At first I couldn’t understand why people would patiently wait for a light to change, even when there was no car in sight. They wouldn’t in France or Italy. I got the idea, though, after I got a ticket, and when my friends refused to go for a drive with me unless I changed my evil ways. I’ve become pretty good about it since,” he grins.

Although when you meet him face to face, Oreste has the sparkle and vivacity of a true star, he is actually modest, unassuming and even retiring, and his style of living is far from glamorous or ostentatious. He is probably one of the least prententious people you could meet anywhere. He lives with his sister Melita in a modest, furnished apartment three blocks from the Paramount studios—by no means a fashionable part of town—drives an Oldsmobile rather than a Cadillac, and so far hasn’t shown any taste for the more glamorous aspects of life in Hollywood.

Oreste’s winning friendliness probably had a lot to do with the unusually relaxed atmosphere on the set of “The Vagabond King.” There was more laughter, banter and good-natured teasing among the cast and crew than is ordinarily found on a studio lot. “I think it was largely because of Oreste’s personality,” says director Mike Curtiz, a first-class veteran. “You never see any long faces when he’s on the set. It’s not that Oreste is a comedian, but he is so good-natured, friendly and willing to go along with a joke, everybody automatically responds to him. He was the star of the picture, but you’d never have known it from the humble, modest way he behaved.”

In the Paramount commissary, for instance, Oreste never sat with the big shots or lunched by himself. He preferred eating with a crowd of extras, stagehands, his stand-in, and especially his two pals, Billy Vine and Harry McNaughton, who are also his boon companions in the film. Billy kept things lively by ribbing Oreste about his exalted stature as the star of the picture. The first time at lunch, he solemnly wrote “star” under Oreste’s signature on the check, signing his own name with “almost star” and earnestly persuading Oreste that this was the thing to do in Hollywood. Another time, during the filming, when Francois Villon and his companions were making a triumphant entry into Paris, Billy complained in mock anger that Oreste was waving his hand to the crowd merely in order to block out his face and steal the scene from him. Oreste obligingly agreed to wave his hand in back of Billy’s head instead.

That one scene, incidentally, turned out to be the only one featuring Oreste on horseback, despite the strenuous riding training he’d had to take for the picture. He took his riding lessons from a former cowboy, who made Oreste jump on a running horse and turn in his saddle at fu gallop firing a gun at his pursuers. One day after a couple of weeks of this routine, the cowboy finally asked him, “What kind of stuff will you be doing?” “Opery,” Oreste replied in his best Western manner tactfully omitting that his specialty was grand rather than horse “opera.”

At any rate the training gave Oreste a feeling toward horses bordering on contempt. One time, when the script called for him to grab the reins of a bucking horse, he waded right in, his head erect and his shoulders squared. “Hey, Oreste,” his double, an experienced stunt man, said to him after the take. “When I do that, I prefer to duck. Next time, I suggest you duck, too.”

However, Oreste had the last laugh when he and Rita Moreno obligingly treated some prissy studio visitors to a sample of “Life in Hollywood.” Staging a kissing scene which left the onlooking visitors gasping, he finally broke the clinch by throwing Rita over his shoulder and carrying her off the set cave-man style. Both of them were convulsed with laughter when he set her down again well out of sight and earshot.

Rita and Oreste got along famously while making “The Vagabond King”—except for one scene in which she had to slap his face, then he had to turn her over his knees and spank her. Quite a number of takes were required, partly because Oreste began to flinch as Rita hauled off and smacked him with increasing realism while he, in turn, paddled her with equal abandon. “I couldn’t sit down that night,” said Rita mournfully. In Oreste’s case, the complaints came mainly from the make-up men who had to repaint, repowder and repair his face after each of Rita’s hearty smacks.

One of Oreste’s major annoyances was the beard he had to sport. Because he had to be comparatively smooth-shaven for part of the picture, he couldn’t grow a beard, and putting on a false one, tuft by tuft, each morning took him the better part of an hour and a half—time he would have dearly loved to have spent sleeping.

Fatigue due to lack of sleep was one of Oreste’s major occupational ailments while he was making “The Vagabond King.” An extremely punctual person (when singing opera, he always arrived at the theatre two hours before curtain time, and he’s never late for an appointment), he always got up at six or six-thirty for his nine A.M. call, even though he lives only five minutes away from the studio. On the other hand, having been accustomed to keeping late hours, he found it impossible to retire early. “I tried,” he sighs, “but I found myself lying awake half the night thinking and worrying about having to get up so early.” While he never objected to the early and long hours as concerned his acting chores, he drew a definite line when it came to recording his songs. “How can anyone sing at nine in the morning?” he asks in wonderment. “Noon is absolutely the earliest can get into the proper frame of mind and limber up my vocal chords.”

Oreste is addicted to watching late-hour TV film shows, likes to read in bed (Shakespeare is his favorite author), and rarely turns out the light before one or one-thirty. When he’s not working, he usually gets up around nine. After a light breakfast (juice, cereal and a “flip”—a Maltese specialty consisting of two raw eaten eggs, some warm milk and a little randy), he practices singing for about an hour, then usually goes for a drive, returning home for lunch. In the afternoon, he works with his diction teacher or singing coach and spends the evening with friends, going to the movies, plays, operas or concerts, or looking at television, reading, listening to records—in short, enjoying himself the same way most people do. In response to the sixty-four-thousand-dollar question about romantic involvements, Oreste shakes his head. “Nothing o far. And I’m not in any rush about it, either.”

The comforts of home are amply provided for him by his sister Melita, who keeps house for him. “Melita is a wonderful cook,” says Oreste. “Unfortunately, I have to watch my weight and eat mostly broiled steaks these days. Neither of us is very happy about it. But Melita always does herself proud when we have company for dinner, though she’s never quite gotten over it that people here don’t eat as much as they do in Malta. After minestrone, pasta and steak, a guest has usually reached his limit, but Melita isn’t by any means through serving the food. She’s always quite hurt when it remains untouched.”

Although all the Kirkop boys are musical, none of the girls has shown a musical bent. “It’s probably not so much a lack of talent as that being an ‘entertainer’ isn’t considered quite proper in Malta, especially for girls,” Oreste says. “Even in my own case, I tried to keep it a secret from my family at first that I was studying singing. When my mother finally heard about it, she said, ‘Why don’t you become a priest and do something for God with your gift instead?’ ”

No true-to-life priest, however, caught Oreste’s imagination as much as Bing Crosby did in “Going My Way.” “Bing is even more of an idol in Malta than he is in this country,” Oreste says. “He was the first star I wanted to meet and asked to be introduced to when I arrived in Hollywood.” Bing recently returned the compliment by introducing Oreste to the public in Paramount’s musical short, “Bing Presents Oreste.”

While Oreste is without a shred of conceit, he is, nevertheless, supremely confident of his own ability as a singer. “When I go to recitals or to the opera,” he says, “I go for my own pleasure—never to check up on the competition. I honestly don’t worry about it.”

Among today’s opera singers, Oreste admires most the great Italian tenor Benjamino Gigli. He is also without professional jealousy and unstinting in his praise of closer rivals such as Jussi Bjoerling and Mario Lanza. Of course, Caruso, whose range, voice and musicianship have never yet been equalled, gets Oreste’s highest respect. “What a pity he died only a few years before modern recording techniques came into use,” says Oreste.

Having tremendous volume, Oreste likes to sing above a full orchestra. After he made his first recording of one of Rudolf Friml’s songs for “The Vagabond King,” the director had to ask him to take it easy, hold back on the operatic verve, and remember that he was singing into a mike. “Holding back,” says Oreste, “was one of the hardest things I had to learn about singing and acting in the movies.”

While he probably wouldn’t refuse an offer to sing at the Met, Oreste is currently looking forward to lots more work in movies. “Singing in opera is extremely hard work,” he admits frankly. “I like making pictures. You reach a much larger audience, the pay is better, and it is much more satisfactory from the point of view of giving an even performance from start to finish. However, I would very much like to have a real operatic role some time in the future.” And since, from a performer’s standpoint, Puccini is his favorite composer, Oreste would no doubt be happiest performing in such classics as “La Boheme,” “Madame Butterfly” and “Tosca.”

When he does, chances are that jukeboxes all over the country will be well stocked with Puccini, as sung by Oreste, instead of “See You Later, Alligator.”

THE END

—BY ERNST JACOBI

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE JUNE 1956