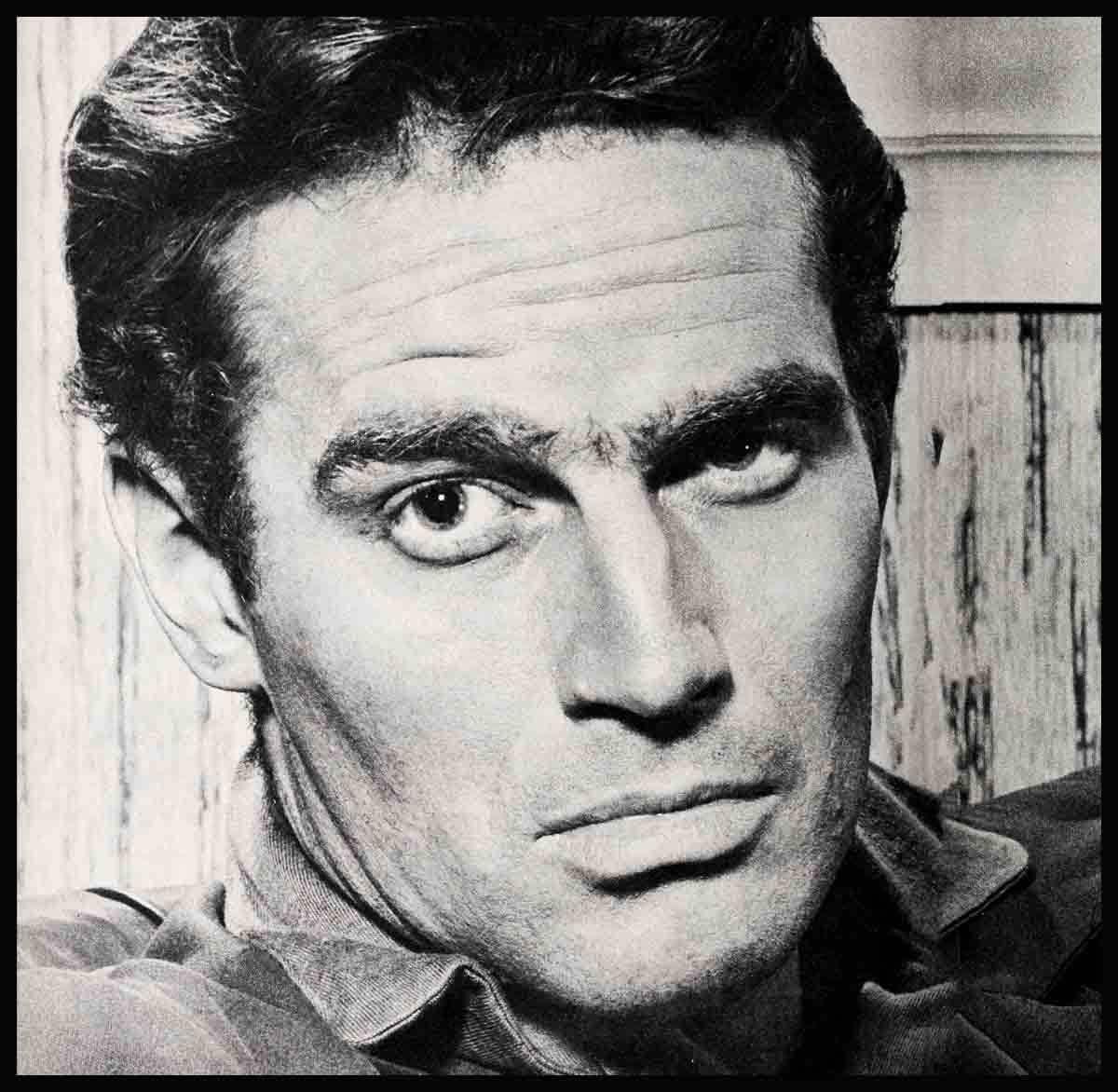

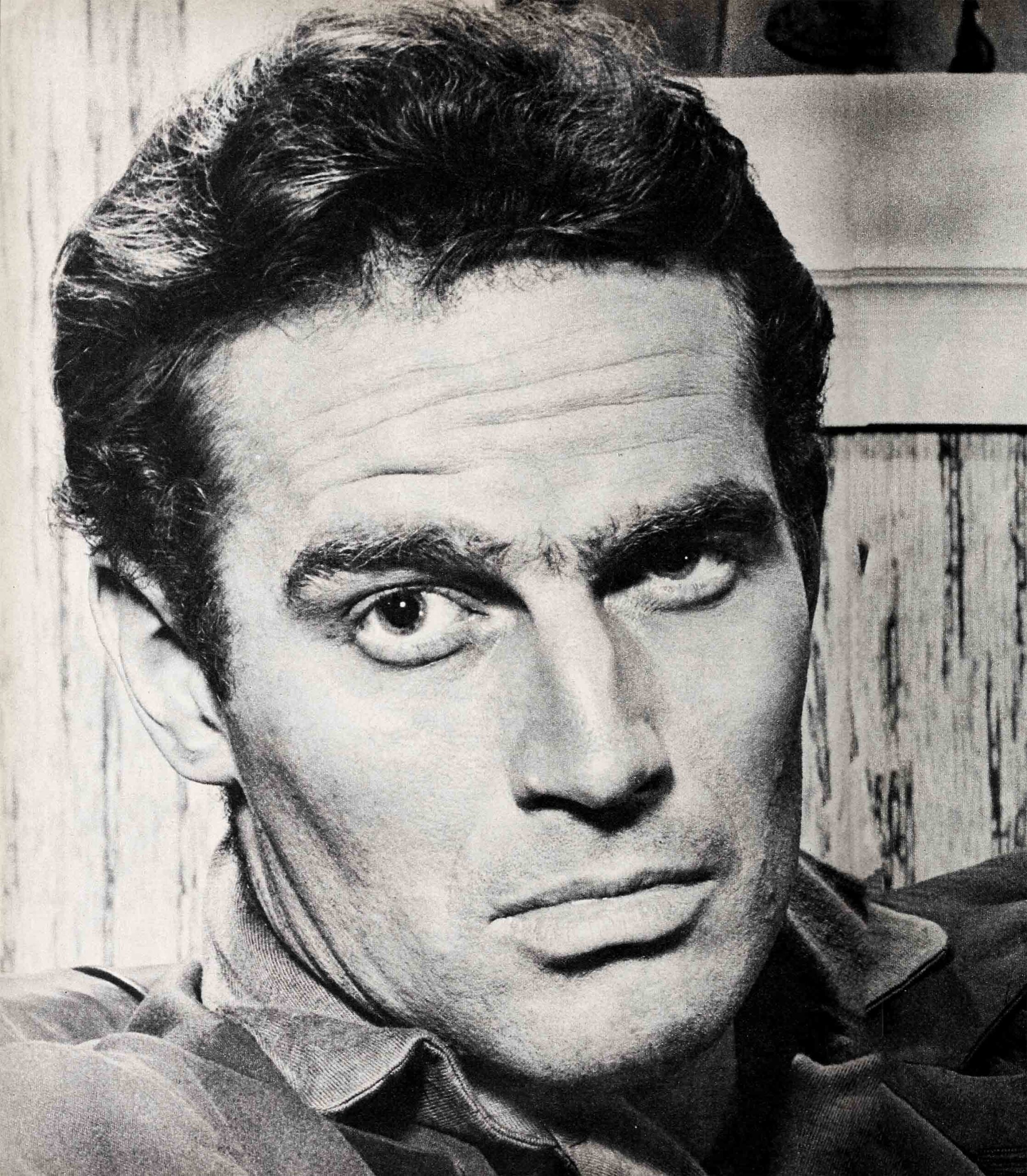

“For If Ye Believe . . .”—Charlton Heston

Jesus said of Moses: “For if ye believed Moses, ye would have believed me; for he wrote of me.”

Can any man play the role of such a figure and not be changed by it? That was the question Charlton Heston asked of himself when he was first approached, by Cecil B. De Mille, to portray the Biblical character in “The Ten Commandments.” Heston now has an answer. It is a definite “No.”

“Moses was the greatest man who ever lived,” says Heston. “Jesus cannot be placed in the same category because He was divine. Moses was the only man who ever talked, face to face, with God. No one can study the tremendous drama of the Exodus which Moses led and not be profoundly moved. No one can live it—as I did in the making of ‘The Ten Commandments’—and not come out a different person. The effect was—unexplainable. The greatness of the man emerges gradually, like dawn, until in the end he towers above any other who ever lived.”

Charlton Heston never pretended to be a profound thinker or to have powerful convictions about his relations with his Maker “Chuck was never an extremely religious person, in the generally accepted sense,” his wife Lydia said after seeing him through the experience of making the picture. “He was reared in a conventional Episcopalian background, but this had no outward manifestations. Now, however, I think he feels that Moses and ‘The Ten Commandments’ have given him a profound insight. Entirely apart from any convictions that he himself may have, I believe his study of the Ten Commandments has given him a greater feeling about many things, including deep respect for the beliefs of others.”

And there was more to the experience that only Charlton himself could tell. No individual can live through a great emotional adventure and emerge in all respects the same man he was before entering upon it.

It began with another man who is remarkable in many ways—Cecil B. De Mille. This shrewd and thoughtful artist had one of the greatest casting problems in Hollywood history. He needed a young yet experienced actor—which Heston, with his list of excellent but far from earth-shaking pictures behind him, was. He needed certain physical qualifications; these, too, Heston, his six-feet-four-inch frame and his strong, expressive face, were able to meet. But more than that, what Mr. De Mille sought and at last found was an innate gravity of soul, a capacity to absorb and then to portray instinctively the most profound human personality ever to appear in the history of the Judeo-Christian religion.

“I had watched Heston closely for some time,” Mr. De Mille says simply, “and the actor seemed to have what I needed.”

In his preparation for the role, Heston read twenty-two volumes of a bibliography on the life of Moses, after he had devoted many long hours to the study of Exodus. In the early days of the picture, a few members of the cast were inclined to ridicule him for his almost abnormal dedication to the role he was to play. During his year of preparation, he never seen on the Paramount lot without a stack of books under his arm. Knowing Heston as a basically gregarious man, others in the cast thought this savored slightly of ham. They later changed their minds, however, when they discovered that he had read all the books he carried with him.

Even Heston’s physical labors in getting into condition for “The Ten Commandments” were formidable. When he was chosen by De Mille for the role, the actor, never a man to toy with his food—his normal lunch is an outsize steak which he devours with all the enthusiasm of a hungry lumberjack—was toting 214 pounds of bone, muscle and not much fat. When Mr. De Mille told him he must slim down to 194, Heston was mildly astonished, but actors don’t argue with the great producer. Aided by James Davies, physical director at Paramount Studios, he went to work. “He slaved ferociously,’ Jimmy says. “From January 17 until May 28, he labored every Sunday except three. Using two fifty-pound weights, he would normally hoist 5,000 pounds each day in a smooth up-and-over motion, Each workout lasted an hour and a quarter. When he got through he was a lot of man.”

The spiritual preparation harder—and more lasting.

During the filming of the picture, both in Egypt and in Hollywood, Heston was at first subjected to some good-natured ribbing, not only because of the seriousness with which he undertook the role, but on account of his striking, almost godlike make-up. This never bothered him, and he gave no evidence of self-consciousness. Gradually the absorption which governed his mind off the set as well as during the actual shooting impressed other members of the cast and crew. During the entire period he seemed more and more thoughtful, more pensive, than his friends had ever known him to be. He became more and more detached, and spent much of his leisure time in his dressing room, listening to classical music. Rallied on this point, he replied that music helped him get into the proper mood.

Lydia Heston recalls that: “He seemed, somehow, withdrawn into himself. One day, after they had returned from Egypt and were shooting on the Paramount lot, I went to the studio and had lunch with Chuck in his dressing room. He seemed unusually thoughtful, and when I left I kissed him goodbye. Immediately I sensed a curious stiffening. Hurt and angry, I blurted out: ‘I’m your wife. Remember?’ It took a minute before he came back to me and the real world around him. Then he laughed, a rueful, almost embarrassed laugh, and said, ‘I’m sorry, honey. This role really must be growing on me. I’m beginning to think I am Moses.’ ”

By that time in the making of the picture, the spiritual impact of their undertaking had affected everyone involved in it. A visitor to the lot, arriving in time for the lunch break, saw the principals and extras in their Biblical robes, bearded and solemn of face, pouring into the commissary and across the street to the lunch counters and cafeterias. Even in blasé Hollywood the contrast between the characters and the world around them was at first ridiculous. Seated at a table in the commissary with Yul Brynner, John Derek and others of the cast, the visitor looked with raised eyebrows across the room to where Charlton Heston sat alone, the Biblical Moses to whom ordinary mortals hesitated to approach. Amid the clatter of dishes and high-pitched chatter of commissary conversation it was, to say the least, odd.

“Yes.” the cast members answered the raised eyebrows. “Maybe it strikes an outsider as pretty silly. But do you know something? Making this picture has done something to every one of us.”

Later, Mr. De Mille, talking about his picture and what it had meant to its cast, particularly Charlton Heston, was seated in his office, a room completely filled with oil paintings of Biblical characters: Queen Nefritiri, played by Anne Baxter; Sephora, played by Yvonne De Carlo; and many pictures of Moses representing the three stages of his career.

Members of the cast, including Heston, Mr. De Mille said, had been taken over the precise route which Moses and the children of Israel traveled in their flight out of Egypt. “I did this for a definite reason,” he said. “I wanted Heston to know, at first hand, the sufferings of the people whom Moses led out of Egypt on their journey from the Red Sea to Sinai.

“The desert,’ Mr. De Mille continued, “was the same ancient wilderness, under the same blazing sun, that Moses stumbled through as the outlaw shepherd who was to become the voice of God. I, for one, am glad this desert hasn’t changed. I went there to make ‘The Ten Commandments’ in the hope that some of Moses’ ancient inspiration would rub off on our modern counterpart, Charlton Heston, and on the crew of Hollywood technicians, including myself.”

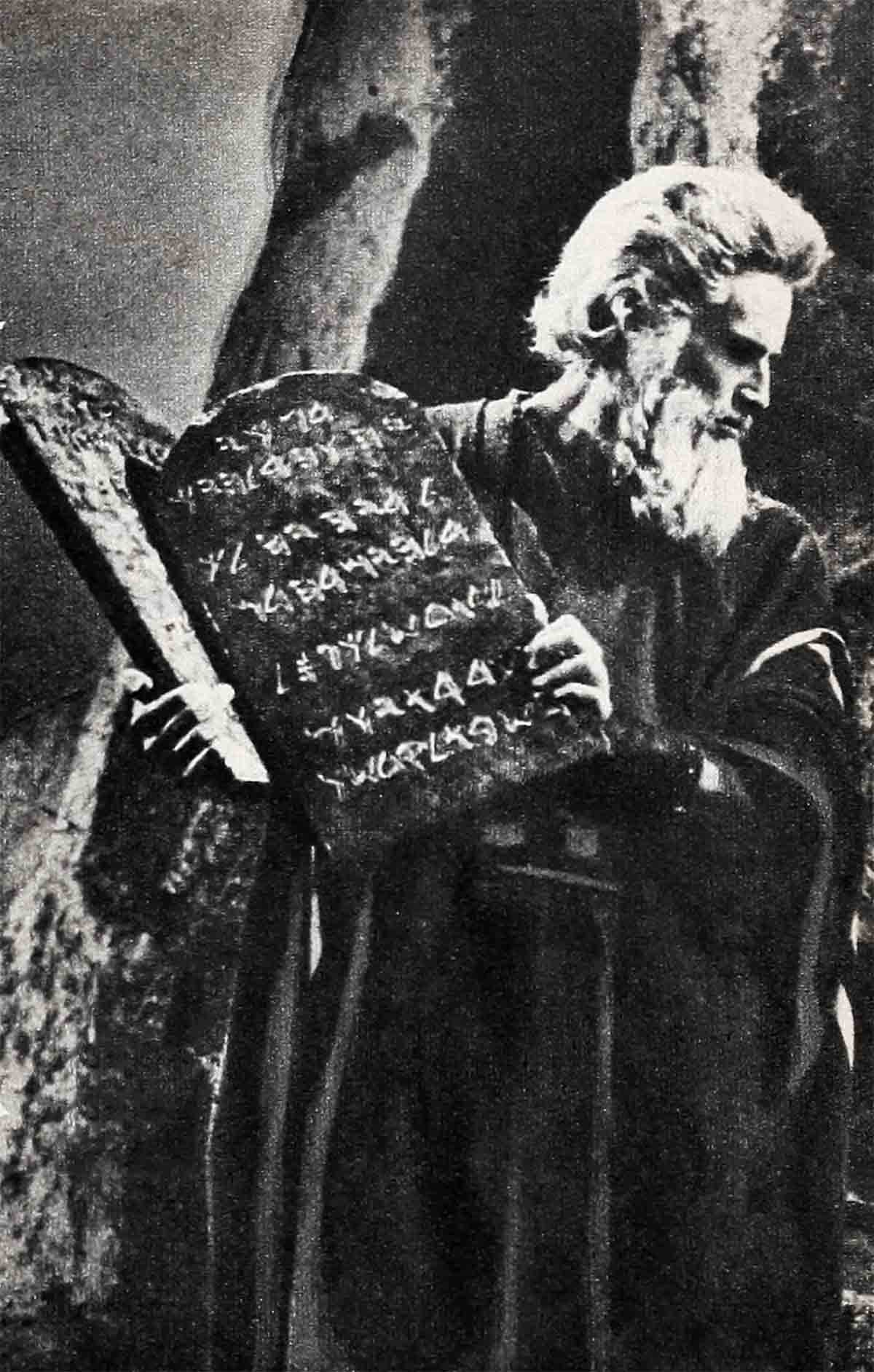

Asked if he had achieved this objective in regard to Heston, Mr. De Mille said: “I cannot see how it could be otherwise. It is impossible to stand on the crest of that most majestic mountain, Sinai, where Moses stood and listened to the commands of God, and not prove the Bible to yourself.”

Continuing to speak of their memorable trek through the wilderness, Mr. De Mille said: “We went down the Nile road to Suez, across the canal, then by car into Arabia, through the Sinai desert to the shore of the Red Sea, then by camel through the mountains to the Wadi Feiran and St. Catherine’s monastery. Then we traveled on foot up Jebei Moussa.

“We shot parts of the Burning Bush and Decalogue sequences on Sinai, and scenes of Moses wandering in the desert on our way back. All of it was strange and wonderful and awesome. I know that Chuck felt as I did. To stand on the peak of Sinai was a deeply moving experience, and to live for five days inside the monastery itself was, perhaps, the most fruitful of all that we saw and did. It was a tremendously emotional experience.”

Anne Baxter, who played the beautiful and tragic Queen Nefritiri (whom, historians say, Moses loved), says: “I think there’s no doubt at all that Charlton was deeply affected by the role he played. Moses, you see, had to be so subtly differentiated in portraying the three great phases of his life—those of the Prince of Egypt, the outlaw shepherd, and the man who led the Israelites to the Promised Land—that it required interpretation of the most delicate shadings. I, as the queen who loved him, could feel how beautifully he accomplished this.”

Speaking of the effect upon him as an actor and as an individual of the great scenes he played in depicting the life of Moses, Heston said: “Any actor worth his salt tries to believe in the events which he is trying to portray. For instance, when I stood before the vast throng of 12,000 people and 5,000 animals, all waiting to begin their momentous journey into the Promised Land, and when I raised my arm and cried: ‘Hear, oh, Israel, and remember this day. . . .’ I was as tight, emotionally, as it is possible for a man to be. Then, in the scene where I stood face to face with God on Mount Sinai, I was so immersed in the enormous implications of what was transpiring that I didn’t have to act at all. You can’t speak those magnificent lines without having your heart leap in your throat. It’s like holding lightning in your hand.

“I always suspected an actor who said playing this or that part brought him closer to God,” Heston went on. “To make such a claim was, I thought, presumptuous. But l’ve had to revise that opinion somewhat. No actor on earth could go through that stupendous role and not feel closer to the Creator.”

The Ten Commandments” is finished and Charlton Heston, whatever effect it had upon him, must go on in the career of a successful Hollywood actor. It might well be asked: Will the great role of Moses make every other picture which awaits him in the future something of an anticlimax? Does the brooding mood which dominated his thoughts during the two years of preparing for and shooting that magnificent epic still press upon him?

While it is not true that the role he enacted in “The Ten Commandments” is still noticeable in his bearing, the impact of the great personality he portrayed remains with Heston to some extent. His buoyancy, which at first glance appears as youthful as it ever was, is diminished. He is carefully meticulous in his consideration for others. He has a new seriousness.

Recently, we watched Charlton closely as he strode through his newest picture, “Three Violent People,” playing opposite the same actress who, with her beauty and consummate art, helped make vivid his characterization of Moses in “The Ten Commandments”—Anne Baxter. It was a post-Civil War story, and it called for violent, uncontrolled emotions. The scene was being enacted in a tawdry bedroom of a sleazy Western hotel, and Heston was playing it as if it were his first big chance before a camera.

When the scene was finished, we asked him, “Did ‘The Ten Commandments’ give you anything that would carry you over into a part like this one?”

Thinking first of his development as an actor, he replied instantly, “No one could work under Mr. De Mille and not come out of it a far better performer.” Then he paused. He was about to speak, and then paused again. Our question, he realized, was far more profound than one relating to mere acting skill. What did he get from having been the great Moses, from having portrayed this tremendous figure in the gigantic undertaking which was “The Ten Commandments”? He seemed to be searching for words and not finding them.

He smiled, and said softly, “I hope it has taught me to play lesser roles better.”

But he knew, as we did, that he had not answered the question. Perhaps he could not. Perhaps no man could. Having been Moses, having talked to God, having led a people through a wilderness to light, having founded a new religion—even if only in make-believe—how could any man express the effect of that experience in simple words?

THE END

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE DECEMBER 1956