Lauren Bacall: “It Isn’t Easy To Kill A Memory”

High above the traffic’s muffled roar, in a New York City apartment, it was past midnight, yet a light still burned low from a window overlooking Central Park. Voices could be heard coming from the library, but the room was empty except for a slim figure of a woman sitting alone on the couch, propped up by two large blue pillows. She was intently watching a newscast on television when, suddenly, with the announcement of “The Late, Late Show,” her expression changed and she got up and clicked off the television set. Walking to the window, she stood there motionless, looking out at Central Park, eighteen stories below. Peaceful and unreal, the pulsating city had at last gone to sleep.

AUDIO BOOK

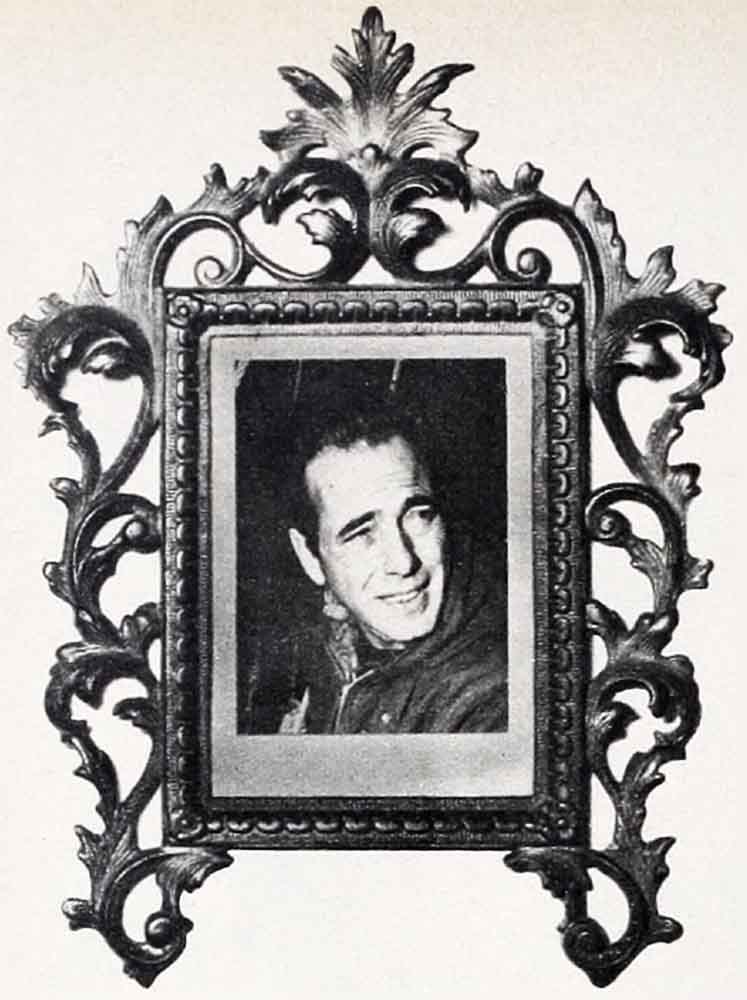

She stood there a long time without moving, and then, almost defiantly, she turned around and walked across the room, turning on the set again. Adjusting the sound, she backed away from the set, not taking her eyes off the screen, and sat down on the couch again. As she watched the picture come into focus, she began to smile, almost hesitatingly, as a cool, slightly arrogant voice said, “If you want anything, just whistle!” Then, for the rest of the evening, and for the first time since her husband’s death three years before, Lauren Bacall sat alone watching Bogey on TV, and reliving a memory. . . .

“To Have and Have Not” was her first picture and their first together.

“I remember the day before we went in-to production on that picture,” she said. “I was so nervous that I was all arms and legs. I was sixteen and had been a model and Howard Hawks had discovered my pictures in Harper’s Bazaar magazine. The first thing he did, when I arrived in Hollywood, was to take me on Bogey’s set to meet the star. I had always been a movie fan but, amazingly enough, Bogey had never been one of my special favorites. To my sixteen years, he seemed like an old man of forty-one. Besides, he was married, so that automatically excluded any thoughts of romance—which I didn’t have, anyway. But I had enormous respect for him as an actor, and even after we had worked together, my worst fears never entirely disappeared.

“Sitting there watching ‘To Have and Have not,’ I remembered the crazy nick-names he used to call me, like ‘Sam’ or ‘Joe’ or ‘Charlie’—’Charlie’ was his favorite—he never called be Betty—and how he kidded me out of my nervousness. One day we were playing a scene together and I suddenly went dry. I just couldn’t remember my dialogue. There was a dreadful silence, and then Bogey just looked at me, and in a low, deadpan voice asked, ‘I beg your pardon?’ I just broke up and, after that, all my tenseness was over. I didn’t muff another line. Another time, I had a scene where I had to enter a doorway and I slouched in like a model. Bogey came over to me and said, ‘Listen, Charlie, have you any idea why you are entering that doorway? Just don’t walk in as if you had come from a manicure and had no other thought in your mind except whether your nails are dry!’ “

Betty stopped talking, as though the memories were stronger than the present and finally, without reason, she said: “Bogey gave me a sense of security. He sheltered me the way my family had. That’s why, after his death, when I was left with the children and had complete control of our future, without Bogey it terrified me. I kept telling myself that there were millions of young wives all over the world who experienced the same. But it didn’t help my loneliness. The panic was still there.

“It remained until, one day, I finally came to my senses. I decided I couldn’t go on living surrounded by the ghosts of the past. I stopped wearing the bracelet Bogey had given me, with the inscription from ‘To Have and Have Not’ and a tiny whistle.

“It had no point to it now. He can’t whistle for you any more, I told myself, so put it away. And I put away the pictures of his yacht ‘Santana.’ I didn’t need them as a reminder of the fun we had, sailing in Catalina, Balboa and the races in Honolulu. The memory of Bogey’s contented face, when he was sailing, was all I needed. So I sold the ‘Santana’ to a fellow-yachts-man who knew Bogey and loved the sea as he did.

“I also sold the house we shared our life together in. Our friends—Hjordis and David Niven, Kate Hepburn, Frank Sinatra, Spencer Tracy, who had come to see Bogey every day to help keep up the pretense with me that everything would be all right, continued to visit me—but Bogey was always with them. Everyone was wonderful to me, but Hollywood is a town of couples—married, divorced, romantic—and I felt like a third wheel and more alone than ever. However, I didn’t have the courage to move away. And then, when I moved into a new house, I chose one in the same old neighborhood—can you beat that?

“I had always traveled with Bogey and the thought of being on my own, in Lon-don and Paris, was more terrifying than staying on in Hollywood. Then, one day, my great friend `Slim’ Hayward said she was going abroad for a six-week holiday and invited me to join her. That did it.

“In London, Vivien Leigh and Larry Olivier gave me a party. Everyone of importance, in the social and theatrical world, was there, and I kept pinching myself to see if I were the same girl who had once fainted at the thought of even meeting Sir Laurence and Lady Olivier. You can imagine what this did to build up my morale—to be accepted on my own, without Bogey, for the first time.

The fatherless children

“Then I came back and made up my mind to live in New York. The children love it and . . .” Betty paused again. “You know, it’s a shame Bogey can’t see Stephen and Leslie growing up. Being a father was quite an astonishing experience for Bogey because, after three childless marriages and at his age, he was sure that the stork had passed him by. When I told him about Stephen’s impending event, at first he was somewhat reserved in his reaction. I think he was a little scared of the responsibility of fatherhood, and also a little jealous that maybe Stephen would trespass on his territory a bit! But after Stephen came, and looked like a miniature Bogey, he was just like all fathers who feel that it is they who had produced their first born. As for Leslie, he adored her, but he didn’t quite know how to play with a little girl. He would balance her on his lap like a delicate piece of china.

“You can try to keep the memory of a father alive for a child, but I don’t. Not with any conscious effort anyway,” she said. “They each have a photograph of him in their bedrooms, and they accept the fact that their daddy is dead. I wouldn’t allow them, though, to attend the funeral and I didn’t tell them about the anniversary of Bogey’s death, either. Bogey would have been the last person to have wanted this kind of morbidity.

“I know there is no such thing as being father and mother to a fatherless child. Leslie isn’t as aware of her need for a father yet, but I hate the fact that Stevie is being brought up in a household of women.

“So, of course, I want to get married again. It is the greatest compliment I can pay Bogey. But, I know now, you can’t go looking for love. It has to find you—aided by the moving finger of Fate. Now that I’ve learned this the hard way, I go out on dates and have fun. I no longer take inventory for possible husband material! But my son,” and she paused and laughed, “mi son has other ideas. You should see the way he sizes up every escort who beat me around. He takes me aside and whispers, ‘Mummy, is he the one?’

“I’ve explained to him and to Leslie that I want a father for them, but first he must be the right husband for me.”

“Too old for her . . .”

And, pausing, as if considering the loneliness of the past three years, she said: “We would have been married fifteen years on May twenty-first. We were married at Louis Bromfield’s beautiful farm in Ohio. I was nineteen.”

And remembering the day fondly, she smiled, “Bogey had hesitations, in the be-ginning, about our ages. He once told a friend ‘I’m nuts about the dame, but I’ll never marry her. I’m too old for her. I’m at that age when I’ve had my fling and want to settle down. She’s just starting her life and needs a young guy who will take her dancing every night and give her a family. I’m too far off from that type-casting . . .” He always kidded me and said he finally proposed because if he didn’t someone else would beat him to it. . . .

“I want my next husband to be someone closer to my age, not only for the children, but for me. Bogey’s friends were all much older than I. So many of them have passed on, too—lifelong friends like Leslie Howard, Robert Sherwood and Louis Bromfield and his wife Hope. They are all gone. . . .”

Betty sat still, then said, “I can finally look at Bogey and not be sad any more. Watching him on the ‘Late, Late Show’ last night, seeing him now as he was when I first knew him, is like a flashback in a movie. And there are no sad memories now, just happy ones, of eleven-and-a-half wonderful years shared together. I realize I have these. How many people can go through an entire lifetime and be this lucky?

“And now, all I want is a one-woman man, as Bogey was,” she said quietly. “I don’t believe in infidelity in marriage. You know, most people think of me as a play-girl, but they couldn’t be more wrong. I’m the type that goes to India to film ‘Flame Over India,’ where I meet the richest maharajahs. But do they decorate my finger with a pigeon-blood ruby, or smother me in sable? They do not. And why? Because they think of me as a nice girl and don’t want to offend me. And do you know something? They are right! If this makes me sound like Miss Virtue I don’t mean it like that. What I mean is, I believe in the ‘togetherness’ of love that builds a home and a family. I was lucky enough to find it once, and I hope I will again.”

“So long, Baby”

She stopped talking and sat thinking, perhaps of a young woman sitting quietly in a bedroom, watching her husband—still and weak—gasp for breath. And know that she was sitting there watching him die. And feeling that she, too, was in a long illness and that she, too, might never recover. Only, she would be alive, yet numb. And a telephone rings downstairs, below in the library, and she listens as someone moves and picks it up, and yet, she knows she has no desire to know who’s calling.

And a slight movement and cough pulls her thoughts back to the bed and to her husband and she realizes, as though it were a new thought, that she has been sitting there for months, desperately trying to hide from her husband that he was dying. And wondering, all the while, “Does he really know? Does he know, even as we dress and shave him and carry him down-stairs every afternoon, at five, for a drink and a smoke with friends, that he cannot lick this cancer?”

Then, aloud, revealing her thoughts, she says: “Bogey never once discussed death with me during all those months that I sat at his bedside, trying to hide the desperate truth from him. He was a great actor and he played out his part magnificently to the end. He knew, from the beginning, that he had cancer, but he really thought he could lick this dread disease as he had licked every other obstacle in his path. But in those final days, he was too perceptive to kid himself any longer—even though he went on kidding me. He faced death as he faced life—honestly and unafraid. When his time came, with his last strength, he merely said, ‘So long, Baby . . .’ and then was still. But what he meant, I’m sure, was `It was great fun while it lasted, but it’s all over now. Tough luck, Baby.’ “

And, smiling a little she went on, her voice hardly audible, “You know, I’ve sent for all my furniture. It has been in storage since Bogey died. But I decided, last evening, from now on I’m going to have a new home of my own. That’s the way Bogey would have wanted it, don’t you think?”

THE END

DON’T MISS LAUREN BACALL IN “FLAME OVER INDIA” FOR RANK AND 20TH CENTURY—FOX.

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE AUGUST 1960

AUDIO BOOK