The Man I Married

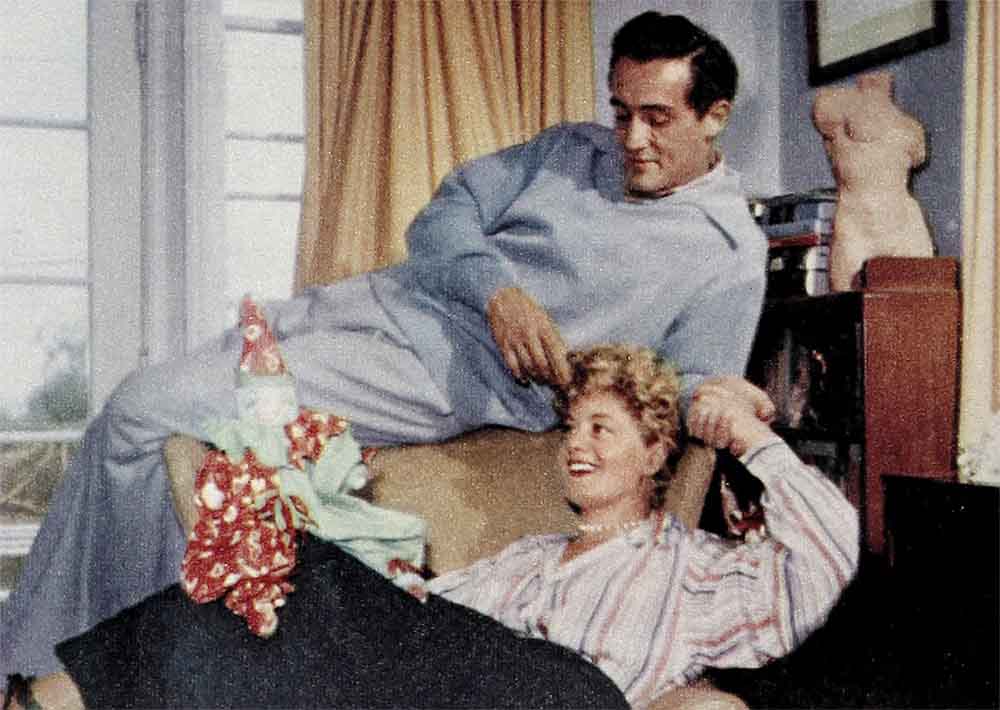

One of the first things my husband asked “news-writers,” as he calls them, when he arrived in the United States was: “Are there any more here like Shelleee?” Since then he has personally assured me there are not. He says I’m a rare species in a class by myself—whatever that means.

After you’ve seen my husband in his first American pictures, “The Glass Wall” and “Sombrero,” I’m sure you’ll ask: “Are there any more anywhere like Vittorio Gassman?” This I sincerely doubt.

Vittorio’s the handsomest, the most intelligent and—in this respect you may quote practically anybody—the most honest of them all. The “news-writers” discovered this honesty when they asked what impressed him most about American women. Without blinking a brown velvet eye, my husband said, “They have pretty legs.” He admits my legs were the features he first noticed about me. As he explained to one writer, “The first time you see Shelleee, you see she has pretty legs. Then you go to the soul. And her soul is very pretty, too.”

AUDIO BOOK

With typical honesty and enthusiasm, Vittorio always dispenses quickly with the formalities. For instance, there was the day he found out he was going to become a father. When he returned from Mexico, where he’d been on location for “Sombrero,” I met him at the airport with our good news. “I think we’re going to have a baby.”

“Is it going to be a boy?”

I weighed the matter a moment. “Yes. as a matter of fact, it is.”

“it is?” Vittorio was so excited that he looked at me as if I really knew.

Of course I didn’t know, but I thought then that Vittorio’s wanting a son would make it so, and chose the name Enrico. But we discussed names for a daughter, too, and when our baby girl was born on Valentine’s Day, while Vittorio was still in Rome, we named her Vittoria Gina, as we’d decided months ago. Sometimes, I would stop in the middle of these practical discussions and ask myself: “Is all this real? Can it be happening to me?” It seems fantastic that your girl Shelley could meet a man and fail in love with him on the second date; walk out of the elevator in the Hotel Excelsior in Rome and see him standing there in the lobby waiting for her and tell herself, “This is the fellow you’re going to marry.”

When I was a kid, I was always making up wonderful stories like this. I would make-believe so much that finally I’d forget I’d made it up—and believe it. There was room in my life for a lot of make believing then. In school in Brooklyn, I had a crush on the husky, red-headed captain of the basketball team, but he wouldn’t even look at me. No wonder! I had buck teeth, straggly blonde hair and skinny knees. But I made-believe he was my steady anyway. I told the other girls he was taking me to the prom—and hoped silently that one of us would drop dead before the night came. When it did come, my mother argued a friend of ours into taking me, and I put up a gay appearance in a home-made gold evening gown.

The next year, I was wearing slinky dresses, dangling a long cigarette-holder and making-believe that I was Jean Harlow. Anybody in the neighborhood would gladly have told you that movies would never be for me. Hollywood agreed when I first came here. I just didn’t fit in. But I got a contract and stayed precisely because I wasn’t like anybody else—Rita Hayworth, Betty Grable, or anybody. Even then, I had the feeling that any minute somebody would tap me on the shoulder and take it all back. I felt insecure in my personal life, too. I made a lot of copy, but the laughs were all on the outside. Until I met Vittorio, inside I was about as happy as the girl in the gold satin dress, stuck with a family friend at the prom.

Nothing that I ever made-believe in all my life could match my real love story, which began in a foreign country—in a foreign language, yet! My Italian was limited to assorted flavors of pizza when I first met Vittorio. But love’s the universal language. Vittorio told a friend later, “I look at Shelleee. She look at me. We know we get along.”

From the first, Vittorio had the advantage over me linguistically. He had taught Latin; he spoke five languages fluently, and even the few words he managed in English were the right ones: “Miss Winters . . . very fine artist . . . ‘Place in the Sun.’ ” It wasn’t until months later that I found he hadn’t even seen the picture. But sometimes the right word at the right time occurs to me, too. He asked, “Would you be happy living half-time in Italy and half-time in America?” I said, “I’ll be happy anywhere you are.”

Of course, we did get into difficulties over the language question. The first party I gave in Rome would have been the International confusion of all time if it hadn’t been for Vittorio’s sister-in-law. She speaks English beautifully, and she was a doll about helping out. As it was, we played charades in three languages, and I never could tell when anybody won. Some of Vittorio’s first love letters are classics, too—written in an Italian accent, with every verb in the wrong place.

Just for laughs, I taught him some pidgin English—but he had a laugh on me later. He taught me some Italian phrases that I thought were very impressive. I tossed off a few of them at a formal dinner one evening. Pier Angeli, director Vittorio de Sica and the other guests got hysterical and finally told me what I’d said. Those phrases were “naughty Neapolitan.” Since then, I haven’t trusted my husband any more. I look things up in my own trusty little Italian dictionary.

I have no talent for languages, anyway. But Vittorio’s picked ours up very quickly. He adds ten words to his vocabulary each day, and he’s even correcting my English now. He insists our daughter will be speaking Italian before I can, and that I won’t know what my own child’s talking about. He may be right. But Vittorio’s so eager to learn English that he won’t speak Italian at all around home. “I have to practice,” he keeps saying. He’s a little selfish in this respect; nobody can just learn a language out of a book—you have to talk it some time. Every time I say something in Italian, my husband answers me in English—and there you are.

But in many ways we’ve always spoken the same language. At our first meeting,

I was impressed by Vittorio’s intelligence, his physical appearance, his magnetic personality and sensitivity, his position as Italy’s most distinguished actor in both theatre and movies. He was the most truly grown-up man I’d ever met. But what really impressed me most of all was the fact that we were so completely—there’s no word in English for it—simpatico.

Sometimes we’ve seemed to be almost alone in that thought. “News-writers” predicted we’d separate even before our honeymoon was over. We have had our differences, to be sure. But my husband likes people who have strong convictions of their own—even when they differ from his, as mine sometimes do. We never really “fight,” he says; we just “discuss.” Unfortunately, whenever a discussion of ours is i reported in print you’d think war had broken out in Hollywood. Vittorio says our discussions are proof that we’ll never be bored with life or each other—and, he says, “That is good.”

By temperament, surprisingly enough for one with even half-Latin blood, my husband is placid, calmly thoughtful, very easygoing. When he does get mad, he just clams up, and sometimes it’s three days before I can find out what’s been bothering him. Gossip columns don’t bother him at all—unless they upset me. Then he calms me down, reminding me that there are more important things in life.

Although Vittorio enjoys working in American motion pictures, the theatre is still his first love. That accounts for the unusual stipulation in his M-G-M contract permitting him to spend six months of every year in Italy. He wants to continue his work as star and producer of classics staged by the Italian Repertory Theatre, backed by his government.

My husband is thoroughly conscientious about this project. Some of the actors in the Italian company read about all the movies planned for him in Hollywood and wrote him that they guessed they’d better, look for jobs elsewhere. Vittorio had ten days off between pictures, and he used them to fly to Rome, then to fly a thousand miles around Italy to towns where the actors lived, so he could reassure them personally. During the fail and winter he proved his sincerity by producing four plays in five months in Italy. “Hamlet” and “Othello” were staged at the Teatro Valle—where we first met.

Wherever he is, Vittorio reads constantly —that is, when he isn’t translating plays from one language into another, or writing letters to friends all over the world, on working on a novel. As for me, I’ve been reading every book that’s ever been written on baby psychology. I’m a walking infant-encyclopedia, and my husband thinks it’s pretty silly. “You should stop reading these things,” Vittorio keeps saying. “The baby will take care of herself. The best thing for parents to do with children is to leave them alone.”

He’s the last word in thoughtfulness. After I became pregnant, I began craving Chinese foods like crazy. I used to think “cravings” were nonsense. Little did I know! Vittorio probably still thinks so, but that didn’t keep him from getting up cheerfully in the middle of the night and going out to find me Chop Suey and Egg Foo Yong with all the Cantonese trimmings. And mustard! I wanted mustard on everything but ice cream.

Vittorio still prefers spaghetti, and I can cook it in eighteen variations now. I’ve always liked to cook, but keeping house is something else. Mine is the free-throw approach, pitching clothes and articles where I can pick them up again most easily. Vittorio’s no help around the house, either; he can’t ever find anything. He’s sort of absent-minded.

To relax at home, he loves T-shirts and slacks, but when the occasion demands, he dresses very well and very conservatively. He won’t go shopping with me any more. I took him shopping one day, and he’s had it. Now he just phones the store and says, “Send the blue ones.” I can’t even get him into an American barbershop. He still prefers an Italian haircut. As for my own hairdo, he says it’s cut “like a chrysanthemum.” Yep, he can pronounce it!

But the American institution of the television commercial is too much for him. Finally, it made him mad. Every time he switched on the TV set, there was somebody looking delightedly into a refrigerator. We went window-shopping while I was visiting him on location in Mexico, and we were stopped cold by a big cut-out in a store window, showing a man and a woman inspecting the latest model, with a sign near-by saying “International Artistes Prefer—Refrigerators.” “Oh no!” groaned Vittorio. Even I couldn’t believe it for a minute. The girl cut-out looking raptly into a refrigerator in a Mexican store window was me!

But we have sentimental as well as comic memories of Mexico. We were married in Juarez. Since the extent of my Spanish is “Si,” I haven’t the faintest idea what vows I made, except that I must have automatically agreed to everything. I don’t know whether the word “obey” is included in the ceremony there, but I wouldn’t be surprised if I said “Si” to that, too. I don’t mean that Vittorio’s the boss. It’s just that I respect his opinions (I keep telling myself).

I’ve changed in many ways since we first met. With marriage, I found you must remember you’re speaking for two, accepting for two, rejecting for two. By the time I had this firmly in mind, I was speaking for three. One of my biggest faults has always been that I couldn’t say “No” to an invitation from friends. Before I thought, I’d say “Yes.” Vittorio couldn’t understand this. “You should say, ‘I’ll think about it,’ or ‘I’ll talk it over with my husband,’ ” he kept telling me. “Then we’ll discuss it, and you can call them back.” He’s very wise, as it turned out. If he hadn’t given me this advice, I’d already have had us booked through 1954.

I guess your whole sense of values changes with marriage anyway. At least, mine has. I think I’ll even be a better actress because of it; I’ll be more relaxed, more . . . simpatico. My philosophy of living has become more like Vittorio’s. He was used to living a quieter life than I was, but I like it, I’ve found. And I was so sick with the “virus” and with other more natural disturbances during my pregnancy that I didn’t feel much like going out anyway. With today’s medical miracles, you’d think somebody would find an easier way to have a baby!

Strangely enough, I don’t miss the festive life any more. I spent some of the saddest and loneliest nights of my life in night clubs along the Sunset Strip. A year ago, I’d have gotten hysterical if I missed a big Hollywood party. Now my feeling is one of relief—that I can spend another quiet evening at home.

To my own surprise, I found myself saying, “Well, no, I really don’t.” And I meant it!

I’m beginning to adopt my husband’s more relaxed and fatalistic philosophy. If I miss a picture that I’ve been anxious to do—I’ll live. I had three offers for good pictures the week after I found out I was going to have a baby. One of them, with Richard Widmark at Twentieth Century-Fox, was a strong part, written for me. But I worried about it. It was a strenuous role that called for getting roughed up a bit. Vittorio’s reasoning was right, as usual: “Do you think this part is another ‘Place in the Sun’? Is it that good? Would it gel you an Academy Award?”

“No,” I had to say. “It’s good, but it isn’t that kind of a part.”

“Well then, why do it?” For the life of me, I couldn’t think of one reason why.

If my career should ever really clash with my marriage, there’s no doubt in my mind about what I would do. I couldn’t be suspended by the studio any more often in the future than I have been in the past And I know now I’d rather be a happy hausjrau than a successful, lonely star.

It’s not that I like Shelley less, but that I love Vittorio more.

THE END

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE MAY 1953

AUDIO BOOK

No Comments