Shari Sheeley: “Die Died In My Arms”

How can Eddie be gone—and I still here? How can Eddie be dead and I alive?” She’d asked herself this question over and over. They were going to spend the rest of their lives together. They had it all planned! She used to say, “Eddie, honey, I feel so lucky. We’re going to have forever with each other. A lifetime, Eddie—a hundred and fifty years at least!”

He’d hug her and laugh at her crazy arithmetic. He always did, except that last day in England, just before they took the cab to the airport, when, instead, he said quietly, “You know, Shari, I’ve got a queer feeling that Fate’s not going to let us. Something awful’s going to happen—I can feel it.” But some people get hunches, especially before a plane trip, and they were flying home. So Shari put her arms around him and said, “Oh, Eddie, don’t think that way. You’re tired, you’ve had a long tour, but it’s over and you’ll have a rest. No one’s going to stop me from being Mrs. Cochran. All that wonderful time shining ahead for us, Eddie. We have everything! Everything’s going too great for anything to happen.”

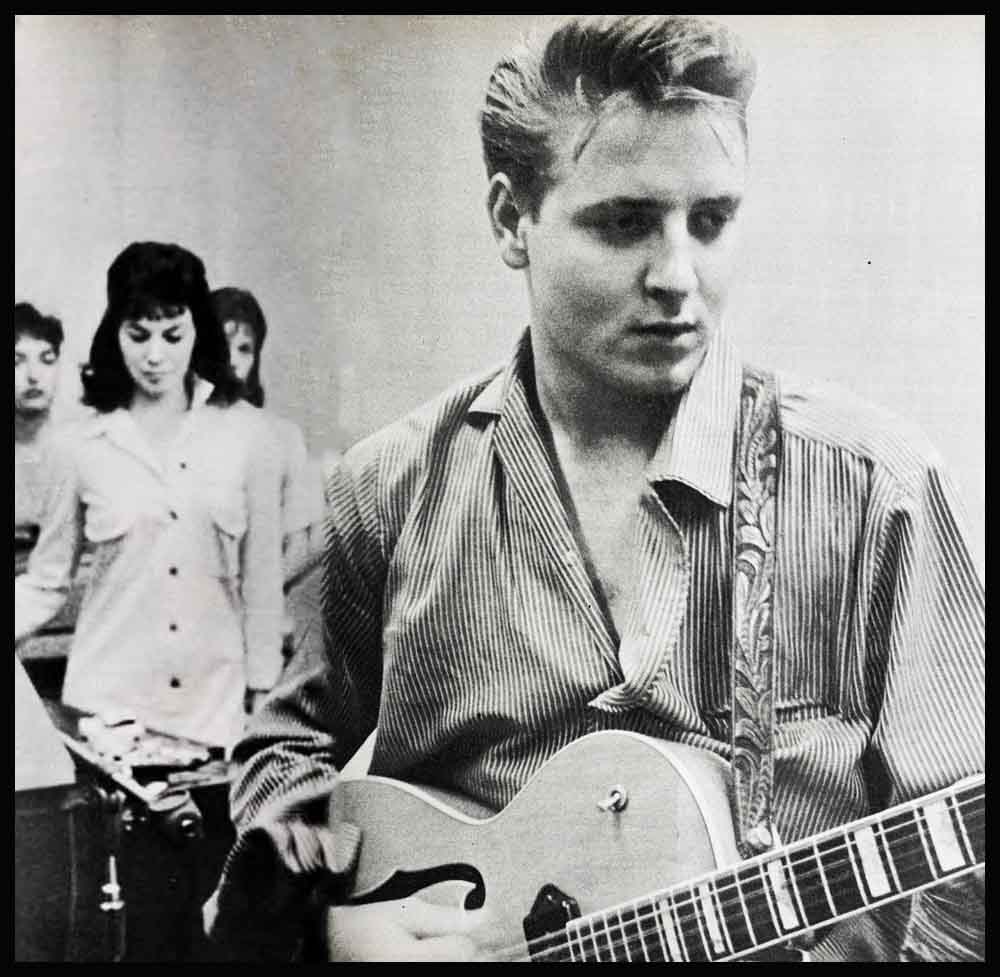

The day before, she’d been watching Eddie from the wings, that last day. The English kids were screaming themselves hoarse for him. She was proud of him, thinking, “that’s my Eddie!” But mostly she loved him. He looked like a little boy when that one stubborn lock of hair would fall over his forehead as he forgot himself in a song. He had a way of pushing it back that made her want to go out on stage and brush it back for him.

Funny, but that was exactly the same way she felt the very first time she ever saw Eddie Cochran. She was doing a TV show and she happened to be back-stage. Even then, not knowing him, she had an impulse to push back his hair with her hand, since it always seemed to be bothering him. She had gone backstage to watch friends of hers, Phil and Don Everly, on the same show, and there was a handsome looking boy with a wonderful smile. He was standing with a guitar slung over his shoulder, waiting to be called on stage. When he went on, she watched. She didn’t seem able to take her eyes off him.

“He’ll never remember me”

After the show, Phil Everly introduced them. “This is Eddie Cochran, Shari,” Phil said. Eddie smiled and said hello; she said hello back. Then he said, “Well . . . so long” and went on his way.

Shari looked after him and thought, “He’ll never remember me.” And forgot to tell him she loved to write songs.

A few months passed. She had written a song called “Love Again.” And she had a manager now, so she asked him if he could show her song to Eddie Cochran. Eddie liked it. She went to his recording session, pretty excited that he was going to sing her song, but not expecting that he’d remember her. She was right—he didn’t!

But when she stood and listened to him singing words that she’d written, she had a feeling that he’d never forget her again. And she was right there, too. He didn’t! They went out afterward for a Coke, and became good friends. In time, they became close buddies—like brother and sister, only better. The more Shari knew him, the better she liked him. He liked her, too. They kidded around a lot, they had fun.

Shari would say, “Eddie, I could listen for hours to that Southern drawl of yours,” and he’d say, “Now where would I get a Southern drawl, reared in Minnesota?”

She knew perfectly well that his folks had moved up to Minnesota when he was a baby, but she’d say, “Well, you were born in Oklahoma, so you must’ve been born with the accent.”

“Absolutely not,” he’d argue. “I’m the youngest of five kids and no Cochran was ever born with an accent.”

Her mother must have thought they were crazy, but she liked having Eddie drop in as much as he did. Her younger sister, Mary Jo, would bring out a batch of cookies and Cokes and they’d sit around the living room singing while Eddie played. It was great fun. Her mother couldn’t get over it when Eddie told them he’d learned to play the guitar all by him-self, when he was only ten years old.

“My folks moved to California when I was thirteen,” he told them, “and I wouldn’t trust any moving men with my guitar. I toted it all the way. My ma said, ‘For pity’s sake, Eddie, with all the other odds and ends we have to carry! That guitar isn’t the prize possession in this household, you know.’ And I said, ‘Possession, Mom? This guitar’s my friend. It’s my best friend.’ “

Her mother had loved that story. She liked Eddie for being the most polite and well-mannered of any of the boys Shari knew. She never worried when they were out together. But Shari wished he wouldn’t be so darn platonic. But she didn’t kid herself about it. She knew that wherever he went there were girls, girls, girls, and she didn’t stand a chance of being his “special” girl. “But,” she says, “I was grateful for what I had—and that was Eddie’s friendship, his nice way of trying to help and advise me on my songs.”

That Christmas, of ’58, Eddie asked her to go to New York. There was to be a big rock ‘n’ roll show in the city, and her manager, Jerry Capehart, would be going along for it. She begged her mother to let her go, pointing out that, besides Jerry being there, her aunt and uncle would be in New York to look after her, too. “They’ll chaperone Eddie and me,” she pleaded. And told her mother how Jerry thought it was important for her to meet disc jockeys and TV people. When her mother gave in, she was so excited, she nearly burst.

New York was exactly the way she had dreamed it would be—full of excitement. She liked the atmosphere at the hotel where a big crowd of show people were staying. One of them, Ritchie Valens, became good friends with Eddie and her, and they soon formed a regular threesome, going everywhere together. Later, she remembered it as the happiest Christmas of her life.

“On Christmas morning,” she told her mother after the trip, “Ritchie left a little package by my door—a pair of lovely ear-rings. But what do you think Eddie left right next to it, Mom? A tree. A tiny little Christmas tree. I was so touched, I cried. Girls by the hundreds were hanging around our hotel, and every time they caught sight of Eddie they screamed and ran after him. And to think he bothered being nice to me. He’s a wonderful friend for a girl to have, Mom.”

No longer buddies

One night, on their way out, Eddie took her hand, pulled her past his flock of fans and hustled her into a taxi. They sat in the back laughing like crazy over the whole thing. Until—neither of them knew exactly what happened, or why—but it happened. They both stopped laughing, and sat looking at each other with a new tenseness between them. Eddie still had hold of her hand, but it wasn’t an easy casual thing any more—they were both too intensely aware of each other. Some-thing in the boy’s face told her they were no longer just buddies—they’d found each other, they were falling in love!

They flew back together, literally in the clouds. On the plane, they talked about everything and nothing, but both knew that things were different between them now. That never, again, would it be friendship alone. There was this feeling of something stronger between them, and if Eddie didn’t talk about it, that was all right with her. They were both too young to say the serious things—marriage and the future together. She was only eighteen and a half then, and Eddie was twenty. They each had so many plans and dreams still to fulfill. He wanted to help his family, and earn enough to buy them lots of things, especially a house. And she certainly wasn’t ready to settle down. She couldn’t even cook, let alone run a house! But to be in love—that was the wonderful thing. For now it was enough and she asked no more!

But soon after they got back from New York, Eddie came over one night, and any-one could tell he had something on his mind. They sat on the couch and she looked at his handsome face. She loved him so much it was unbelievable.

But she still didn’t know what he was going to say.

“Shari . . . will you . . . would you marry me?”

She could feel her heart turning all the way over inside. She stared at him, and turned so numb, she couldn’t answer at first. And, then, all she could think of to say was, “Marry you—when, Eddie?” He made such a helpless gesture with his hands that she was almost sorry for him.

“Well,” he mumbled, “well—soon.”

That was when she said the crazy thing, “Oh, I don’t think so, Eddie.”

One look at his face and she realized what she had done. He looked the way a darling puppy would look if someone he loved had kicked him.

“Oh Eddie!” she cried. “Of course I’ll marry you. I only meant not so soon!” She was laughing and sort of crying, at once, and he put his arms around her.

“Oh honey, you know I love you,” Shari said, “but there’s all the time in the world for getting married.” That was the first time she said, “We’ll have a whole life-time, Eddie—a hundred and fifty years together.” And that was the first time he laughed over her crazy arithmetic. And the first time he kissed her. How happy they were that night. Light-hearted one minute, and the next so serious about all they still had to accomplish.

A few days later, Eddie came to the house and handed her a little box. In-side, was a beautiful silver bracelet. He put it around her wrist and closed the catch. She looked at the gleaming silver and knew that, someday, it would be on the same hand that held his wedding ring. But that was a long way off.

After the night Eddie proposed, being separated wasn’t easy. Whenever he went on tour, she would follow his itinerary and wait for his calls. He was always on the move, but every mile he traveled brought them closer to their goal.

The news bulletin

When she couldn’t talk to Eddie on the phone, she could at least listen to his voice on records. She’d drive along, fiddling with the car radio till she tuned in on something of his, and then move along blissfully, her eyes on the road, her ears on Eddie. And her heart with him, too. That’s what she was doing, one day, when a disc jockey broke in on the program to bring a special news bulletin. “Three rock ‘n’ roll singers killed in plane crash . . .” She shuddered, so relieved that Eddie wasn’t flying this time. “Buddy Holly,” the flash went on, “the Big Bopper . . . and Ritchie Valens.”

Ritchie was dead! Sweet, dear Ritchie—dead!

“I almost drove my car of the road,” Shari told about it. “I came home hysterical and collapsed. I couldn’t get it through my head. Eddie, Ritchie and I—why, we’d been an inseparable threesome all through that great time in New York. Now Ritchie was gone. I called Eddie, but I was so shaken, I couldn’t think straight. He was broken up, too, but he tried to calm me down. He talked and talked till I got control of myself. I said, ‘Oh Eddie, what would I do if I didn’t have you to cry on?’ And he said, ‘Don’t think about it, Sweetie, because you always will have me.’ We talked for hours, until I felt better. After that I could bear to hang up.”

But when she had to go to Ritchie’s funeral, with Eddie still away, she broke down again. At the sight of the little brown coffin, all she could think of was Eddie and Ritchie and herself in New York, dreaming their dreams together and making their plans. Ritchie had accomplished one of his, he had bought his folks the house he wanted for them—and now a plane had put an end to the rest of it!

So she stood there and cried, and needed Eddie terribly. She needed him to lean against while she cried. When he got back from his tour, she crawled into his arms and felt she never wanted to leave them again.

Nevertheless, there were times when they’d argue and even break up. Then she would date other boys, burning up inside because Eddie had hurt her. Or else they’d quarrel over something she said to make him mad. But every time they broke up, it was only a matter of time before they got together again. She was deeply in love with Eddie, there was no fooling herself. The kind of man she wanted and needed was one she could look up to with respect as well as love. And that was Eddie! Sometimes she teased him, “You make me just miserable enough to know I’m in love.”

“When Eddie sang,” she told friends, “I always felt warm and wonderful inside. I loved going to his recording sessions and listening to him cut a record.” One night she stood listening, and knew that this was a very special occasion—great and sad at the same time. Because at six o’clock next morning he’d be taking off for a tour of England, playing all the big-time spots like the Palladium in London. “He was going to be gone thirteen weeks,” she said. “More than three months—and I’d miss him terribly. But, when he got back, we’d go on making our plans. Plans for always being together. Secret plans that only Eddie and I knew about. Plans I found so hard to keep locked up inside me!”

Listening to Eddie that night, she thought, “He won’t get any rest at all.” The recording session had started eight o’clock in the evening and it would go on until everything was perfect, even if it meant going straight to the airport from the studio. But, finally, Eddie walked over to her and said, “We’re all through, Honey. How did the session sound to you?”

“Great . . . just great.” They walked outside. It was early in the morning. In a few hours, he’d catch his plane. But for now it was so late that he insisted she go home, not come to the airport. Before he called a taxi for her they kissed and said goodbye, there in the half-deserted street. They kissed again and made their promises. He’d write often, and send all his stories clipped from the English newspapers. And she would write even oftener. She said, “Eddie Honey, it costs a fortune to phone from overseas, so I won’t expect calls. Save your money. Save it for when you get back—save it for us.” He grinned that big grin of his, kissed her again—and then he was gone. She went home thinking, “Thirteen weeks are going to feel like thirteen years.”

She was proud and lonesome

Wherever he went in England, Eddie sent postcards and hastily scrawled letters. She kept a map on her dresser and every day tried to pinpoint exactly where he was at any given moment. When she’d find it—some little town in the middle of England—it looked so far away, that she felt more lonesome than ever. But she was also very proud, because all the reports said Eddie was playing to packed houses. The teenagers of England had taken him to their hearts, her Eddie was a smash hit. And every mile he traveled, was one closer to their goal—the happy time in the shining future when they’d always be together.

She kept marking off days on the calendar. January went by. And so did February. In March, Eddie had been gone eight weeks. She told herself, “Five weeks more and he’ll be back—just in time for Easter. And then we’ll tell our folks we’re serious about each other.”

One evening, her younger sister Mary Jo went to a show and their mother visited friends. Shari chose to sit home and listen to music—Eddie’s music—the voice she missed. She stacked her phonograph with his records and played them over and over.

When Eddie sang a slow ballad, his voice was deep and soft and it made her feel funny inside. But when the next disc came on and she heard him do the rock ‘n’ roll song they’d written together, “Some-thin’ Else,” she smiled at the lilt in his voice, the laugh in it. That slight Southern drawl that she loved.

One minute she was smiling, hearing him sing their song—and the next, she was missing him so bad she started to cry. That was when the phone rang. She wondered who’d call so late, nearly mid-night—but she ran, her heart pounding with a sudden intuition. And she was right. A far-away voice said, “This is the overseas operator. I have a call from England for Miss Sharon Sheeley. Are you Miss Sheeley?”

“Yes, yes, I’m Sharon Sheeley,” she shouted, as if her voice could carry clear across the ocean. And then she heard his!

“Shari . . . honey . . . how are you? Me? Oh I’m fine . . . everything’s going great! But Shari, I miss you . . . I need you . . . Shari? Can you hear me?”

She nodded her head yes, and tried to hold back the tears. “Yes, Eddie, I can hear you . . . and I miss you too. But it won’t be much longer now. You’ll be home in less than five weeks and . . .”

“Five weeks is a long time, Shari,” Eddie said. “I was hoping—maybe your mother would let you come over here.”

She nearly dropped the phone.

“Oh Eddie,” she cried, “I’ll ask Mom—I’ll beg her!”

“Tell her my tour manager will take good care of you, Shari. He says he’ll be your chaperone. Try to come, Honey?” His voice was so eager, she thought she’d die hearing him.

“Eddie, if Mom says yes. I’ll take the first plane I can get on,” Shari said, all excited. “I’ll send you a cable the minute I know, one way or the other . . .”

“Try to make it yes, Shari.”

“I’ll try, Eddie. try.” She made him say goodnight then. This call was costing him a fortune. And they were going to need the money—for that future of theirs.

“Mom, he’s lonely!”

After they hung up, she felt she couldn’t go to bed; she had to wait up and settle everything or she’d never be able to sleep. It was an awful lot to hand her mother all at once. “Mom, Eddie wants me over there so badly. He’s lonely, Mom.”

Her mother said slowly, “I didn’t realize things were this serious between you two . . .”

“They are, Mom. Oh please, please can I go?”

The answer, finally, was yes. But even then, she didn’t tell her mother the whole story. She wanted to wait till they got back, till she and Eddie, together, could tell Mom, “We want to get married.” Like Eddie wrote in a song . . . one step at a time!

Next day, her mother was driving her to the airport and Shari was saying ex-cited goodbyes. “Yes, Mom, I’ll call the minute I land . . Yes, I promise I’ll write every other day . . . Yes, you can count on us being home by Easter Sunday, Mom. Eddie said the tour’ll be over April 16—so we’ll fly home that night.”

One minute she was kissing her mother goodbye, the next she was flying high and, half a day later, she was in Eddie’s arms. The whole fantastic thing was hard to believe. Especially that they were together again. At every show, she sat in the front row, or else stood backstage in the wings, her heart thudding as she heard the wild cheers and applause. The few hours they had a chance to be together, they’d sit holding hands and talking of the future.

“Should we live in an apartment, Eddie?” she asked. “With you always on the go touring, maybe a hotel would be better.”

“You’re going wherever I go,” he said. And then, “I’ve got a swell idea, Honey. Why don’t we live in a tent?” They broke up laughing. Their love was always like that—fun. They could be serious one minute and laugh their heads off the next.

In the serious moods, they realized the time had come to settle down; to pool their resources; to work hard together, so two families could be taken care of besides themselves. They made great plans. And the best part of it was that both were so young, yet—Eddie just twenty-one, Shari nineteen, No—twenty. A few days after she arrived in England, she and Eddie celebrated her twentieth birthday—on April fourth. She thought, “How wonderful to leave my teens behind and turn twenty with such a beautiful future staring me in the face. Twenty—and a whole lifetime ahead to be shared with Eddie.”

They had it all worked out. Easter Sunday they’d be back in California, and that would be the perfect time to tell their families that they planned on being married. No fuss, no fanfare, no elaborate wedding. Just something simple, and as soon as possible.

On Friday night, April 15, she and Eddie together phoned her mother, to say they were definitely leaving right after his last show, in Bristol, the next night. Mrs. Sheeley said she’d meet them at the airport Sunday and that she could hardly wait to see them.

By Saturday afternoon, Shari was all packed. Everyone who was riding to the airport together, that night, brought their luggage to the theater and left it back-stage. Then, when Eddie went on, she stood in the wings watching him work as she’d done so often. And watching him brush that stubborn lock of hair back.

And then disaster

After every number, the audience cheered louder and louder. It was Saturday night . . . date night . . . all the girls and their best beaus were out front And there she was, close to her best beau as he stood in the spotlight and sang. He came to his finale, a big loud version of “C’mon Everybody.” The audience joined in, clapped in rhythm and cheered wildly. . . .

As soon as the show was over and they could get through the crowds waiting for autographs, they grabbed a cab. They had a long drive ahead, to reach the London airport in time for the flight. It was just after midnight when they settled back in the cab—already the beginning of a new day, Easter Sunday. “How miraculous,” Shari thought, “in a matter of hours we’ll be across the ocean . . . across the continent . . . and landing in Los Angeles.”

There were four in the back. Eddie and another performer, Gene Vincent; Eddie’s British tour manager, Patrick Tompkins, and Shari. Only Gene was calm enough to settle back in the seat and try to catch a few winks. The rest sat and talked, Shari and Eddie with their arms around each other, while the driver up front drove through the dark deserted streets toward London. He drove fast, she thought to her-self. “Too fast.” They were almost flying along the ground, it frightened her. He kept racing to get to the plane on time.

She couldn’t bear to tell anyone the rest of the story. Those who love her had to find out from others about a speeding car, and a driver who lost control. . . . The man at the wheel about to plow into another car, swerved frantically, and the cab crashed into a lamp-post. The back door flew open, Shari and Eddie were torn from each other’s arms and bodies were tossed out like rag-dolls, to sprawl in the road in crazy, unreal poses. A boy with a guitar case still clutched in his hand lay unconscious, his guitar smashed to bits . . . And a few feet away, a girl lay moaning, trying to call “Eddie . . .” before the black nothingness closed in on her.

As the first rays of an Easter Sunday sun were rising over the rural town of Bath, England, the doctors and nurses of St. Martin’s Hospital were ministering to the accident victims. Gene Vincent was being bandaged for a painful shoulder injury. Patrick Tompkins was slightly hurt. The cab driver had come through without a scratch.

He couldn’t say goodbye

Down the hall, in another white room, a girl lay in absolute stillness, her young body cruelly broken with multiple fractures. But she felt nothing, she was under sedation. In the brief moments, when she struggled back to consciousness and called a name, they soothed her to sleep again. How could they tell her? How could they tell her that Eddie was dead!

Eddie—He never regained consciousness. . . . He never had a chance to say goodbye.

For days, the girl hovered between the dark and some glimmerings of awareness. Her mother had flown to her side, and when she moaned, “Eddie . . . Eddie . . .” her mother soothed, “It’s all right, darling, it’s all right. Sleep, darling, sleep.” The doctors said it, too, and the nurses. But somehow she knew it was all lies! She was bandaged from head to toe, not one muscle of her body could move, but her heart still had a beat and it beat out the truth. Eddie was gone. Eddie was gone.

She wanted to give up the fight, then. And, indeed, a priest was called to administer the last rites. But her time to die hadn’t come. Slowly, very slowly, she emerged from the tortured darkness, to the world of the living—only to awaken to a worse torture. She would live, she would recover. In time, her body would be well. But who could say whether the scars in her heart would ever heal?

And only to her mother, she asks the pitiful question: “Oh Mom, Mom, I always said we had so much time ahead to be happy together. A hundred and fifty years, I said—and Eddie always laughed. But Mom—without Eddie—what am I going to do for a hundred and fifty years?”

—MARCIA BORIE

A MEMORIAL ALBUM, “EDDIE COCHRAN” IS ON THE LIBERTY LABEL, WITH ALL THE ROYALTIES TO GO TO EDDIE’S PARENTS. IF YOU WANT TO WRITE TO SHARI OR SEND GET–WELL CARDS, ADDRESS HER CARE/OF PHOTOPLAY, 321 SOUTH BEVERLY DRIVE, BEVERLY HILLS, CALIFORNIA.

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE AUGUST 1960

No Comments