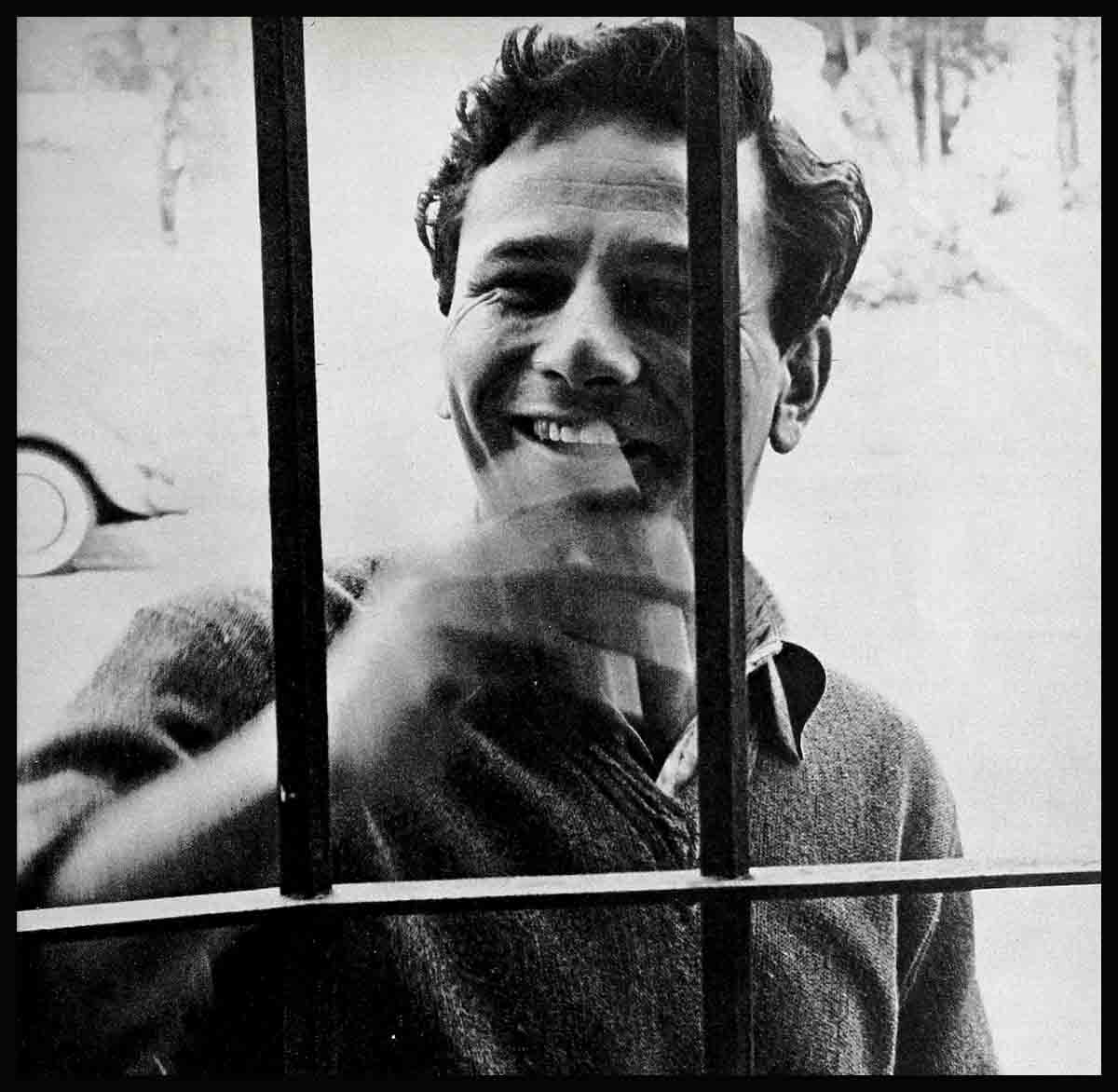

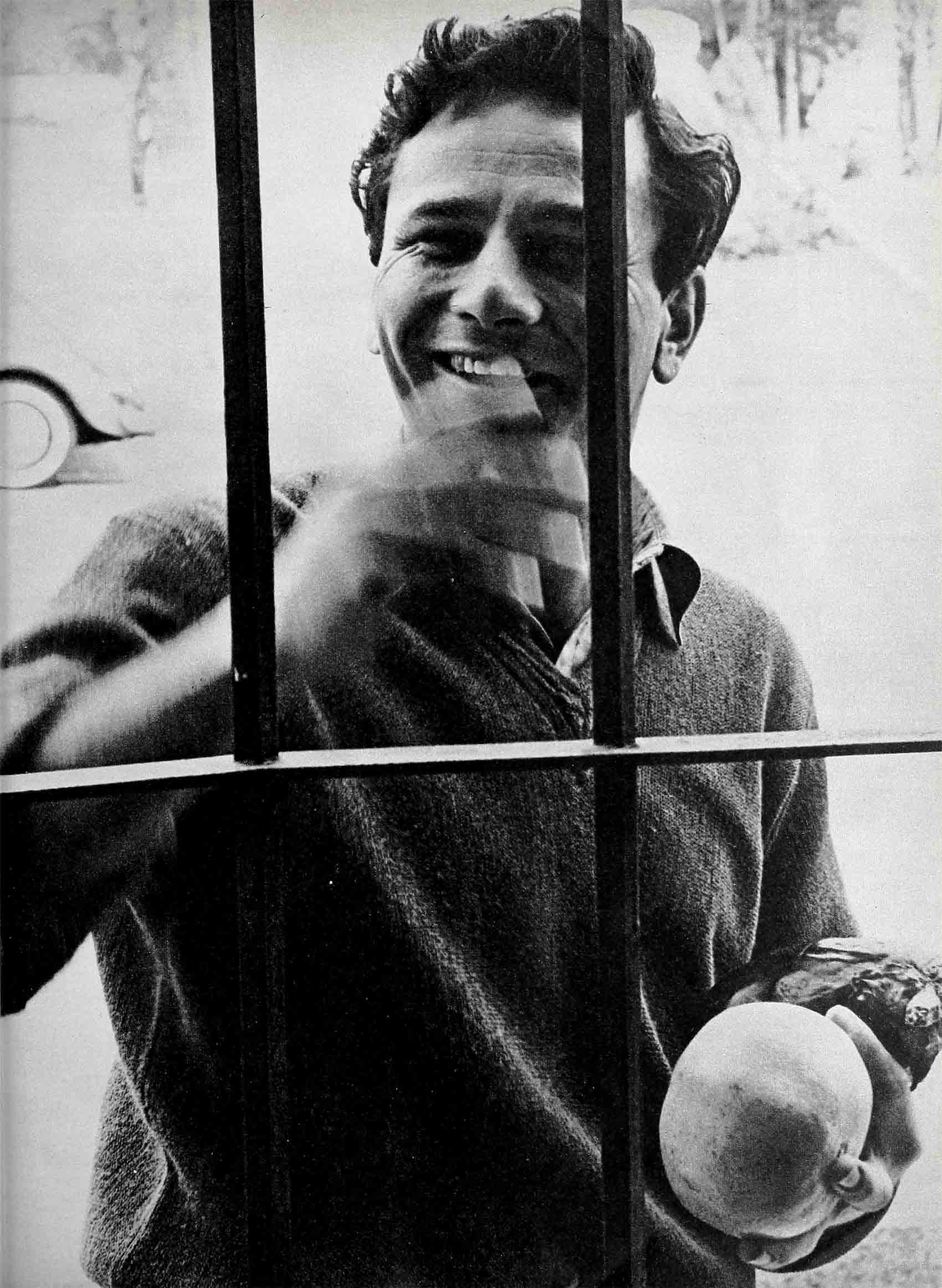

Visiting Day At The Peter Falks’

Peter Falk—who is he? For one thing, he’s very much in. And to make sure he stays in, there are bars on the window. To remind him of his home town—Ossining? “Yeah.” he says, “I’m doing a stretch in a Spanish hacienda.” He is doing a stretch, in movies. And it’s likely to be life according to columnist Sidney Skolsky, who knows about such things, and who said, months ahead of the announcement, that Falk would be nominated for an Oscar for his supporting role in “Murder, Inc.”

O.K., he’s a good actor, maybe a great actor. But what else does he do behind those iron bars? There’s only one way to find out—go in and see. That is if you can get in—those bars work two ways, and one of their most important functions is to keep out phonies. But, if you do get beyond the bars, there’s a lot to find out. If you’re a stranger, he’ll be very shy; if you’re a friend, he’ll be warm and friendly and do imitations for you; and if you’re a Boris Lurie modern painting, he’ll flip over you. If you’re a foreign film, he’ll go out to see you. If you’re a baby, you don’t belong in the picture—not yet, but soon, maybe, because he wants lots of you. And if you’re a pretty girl with brown hair named Alice, you’re his wife. And if you’re his wife, you love him and understand him, and you know why he thinks the way he does and what makes him so strong and what gives him the courage to be him. You know about that July morning a long time ago when Peter the boy became Peter the tough guy. And that’s what he is now—tough. He got that way all in one day.

The sun shone brightly along Ossining’s Main Street that July, two months before Peter was to reach his twelfth birthday. His hard-working parents had left early to open their small department store that stood between the town movie house and the ice cream parlor run by the friendly German couple who liked to give young Peter an extra scoop of strawberry ice cream because his eyes could look so wistful and pleading.

“One look into those puppy-dog eyes,” Frau Schmidt would tell her husband, “and he got us giving him the store for nothing.”

And her husband would laugh loudly, recalling all too well how many times Peter had milked him out of a little more strawberry syrup, or an extra drop of malt by the soulful stare of those deep brown eyes.

But on that sunny morning in July of 1940, the day was beginning to turn dark for Peter Falk. He woke slowly from the sound sleep that had enveloped him for eight, long hours. He tried to focus his eyes, but things seemed dim for the longest time.

“It must be early,” he murmured to himself, “it’s still dark outside.”

He got out of bed to look for his baseball glove, the one he knew would carry him to the New York Yankees—the pride of the baseball world, the champions, his idols. He fumbled about where he was sure he had put the glove, but it didn’t seem to be there. He was sure it was behind the small dresser. He reached behind the again, feeling slowly for the five-finger leather mitt. Then. suddenly, he tripped over the baseball bat that lay below him.

Peter sprawled down on the carpet, then shook his head and began to rub the bruise on his left arm. He was glad it hadn’t been his right arm. for that was his pitching arm. He wondered if his mother had heard him fall. and whether it had awakened her and his father. He heard no sound, and figured they were still sleeping. After all, it was still dark, and they didn’t leave for the store until it was light outside, usually about eight in the morning.

“Where is that glove?” Peter wondered. as he groped his way back toward the dresser. “Maybe I should go back to sleep,” he thought. “Maybe I haven’t slept enough.” He hadn’t been sleeping well lately. He’d been having headaches that sometimes kept him up at night. That—and thinking he had mapped out his life to a fine point. He knew he’d be going to Ossining High in two more years, make the baseball team and then receive dozens of scholarship offers to go to college for his hitting and pitching talent and for being a good student, of course. But he would turn them all down to sign that contract that the Yankees would have waiting for him.

Then . . . he bumped his head against the dresser. He realized, with a strange, sinking feeling in the pit of his stomach, that he hadn’t seen the dresser at all—not until his head had slammed against it. He lay on the floor, trying to focus the dim outline of the room, but all he could see were vague shadows and dim forms.

“Mama! Mama!” he screamed, but there was no answer.

He lay still for a long time, wondering why his mother did not answer him. Where was she so early in the morning? He heard the ticking of the clock, and he moved slowly toward the sound. He reached up. felt the clock in his hand, and tried to convince himself that it was early dawn. He heard the clock loud enough and clear enough, but when he tried to read the numbers, there was nothing. Nothing at all, except to know that there was a clock, and it was ticking, but that was all.

All day Peter lay very still on his bed. afraid to move. He heard the shouts of his playmates going off to play ball and he knew, deep in his heart, that he would never play ball in Yankee Stadium, and he would never wear the white flannels with the black pin stripes and the word “Yankees” scrawled across the chest.

“I can’t see”

That night his parents found him huddled in his room, and in his frenzied cry. “I can’t see anymore, I can’t see. Mama.” they knew that their trial had begun. It was just as the doctor had warned. He had told them this might happen when Peter was three, and the sign of a tumor had begun to show. That night they hurried him to the General Hospital in Ossining. The next morning he was taken to New York City to see a specialist. That afternoon, Mr. and Mrs. Falk heard the news:

“He’s got a tumor. It’s affecting both of his eyes. He may be permanently blind . . . unless we can operate immediately.

The risk was great, but the potential loss was greater. The doctors operated, and after three long hours, they applied the bandages and hoped for the best. Peter lay flat on his back for six weeks. He knew he’d have one glass eye for the rest of his life, and he wasn’t sure that he’d even be able to see out of the other one. His dream of playing baseball was over. Then, finally, the day came for the bandages to be removed. His mother and father were present, and Peter could scarcely breathe, he was so nervous.

“Are you ready, Pete?” asked the doctor.

“Yes . . . doc, I’m . . . I’m ready.”

Slowly, carefully, the bandages were cut away. At first, Peter could see nothing. He tried desperately to make out the figures near him, but the light refused to penetrate.

“Can you see anything, Pete?”

The doctor’s voice seemed so far away. Peter strained to clear the wall of darkness that engulfed him, and slowly, very slowly, the streaks of light began to break through his prison of darkness.

“I . . . I . . . yes, yes, I can see! I can see Mama . . . and Pop . . . and you, doc.”

They kept him in the hospital for another week, then he returned to Ossining with his parents. It was another six weeks before he was allowed even the simple pleasures of reading his favorite stories for more than a few minutes, or seeing a movie, or even looking at his mother’s magazines.

Peter says now, “My dream of a big league baseball career was over, because my left eye never came around as strong as it should have. But I did play baseball again, and even made the high school basketball and track teams at Ossining.”

His struggle to show the other fellows that he would never take their pity reached its goal when he won his varsity basketball letter for playing guard in 1943, 1944 and 1945, his graduation year.

He tried to enlist in the Marines, the Army and the Navy, but his glass eye kept him from making it. So he joined the Merchant Marine, and served during the last days of World War II.

He was restless

Returning from the Merchant Marine, Peter decided to enroll at Hamilton College in Hamilton, New York. He stayed there through 1947 and 1948, but then he became restless. He transferred to the University of Wisconsin in Madison, Wisconsin. At the time, acting seemed the furthest thought from his mind, and except for an incidental part in “Saint Joan” at Hamilton, where he had to be practically pushed on stage, his thoughts of the theater were non-existent.

“When I’d been sick and laid up after the operation,” he explained, “I’d been the star, director, writer and audience to my own dreams and fancies, but really acting wasn’t what I wanted. Not then.”

After Wisconsin, he attended the New School in New York City, but in the spring of 1950, he got so restless again he left for Europe. He traveled through Yugoslavia, Italy, France and Austria until his money ran out and he had gotten that restless feeling out of his system. When he came back, he decided to finish his schooling at Syracuse University. He got his diploma in Political Science from Syracuse’s Maxwell School, and he met Alice Mayo who, six years later, was to become his wife.

“Everytime I asked her to marry me she said no,” Peter quips today, “until one day she figured I might make something out of myself, so she said yes!”

But Alice had good reason to be reluctant. She knew how restless and impulsive Peter was, and she was afraid he’d never settle down. Even after Peter had gotten a job as an efficiency expert with the Connecticut Budget Bureau and had worked for them two years, he suddenly announced one day that he was giving it all up to become an actor. No wonder she was afraid of a marriage with him. But what Alice didn’t see then were Peter’s greatest qualities—his strength and the courage to search for what he really wanted from life. When he found something that could satisfy him, he would pour all his energy and all his love into it. And that “something” turned out to be acting.

How it happened

Unknown to Alice, Peter had one day driven down to the White Barn in Westport, Connecticut, to see a friend. There he saw Eva LeGallienne, the great actress, teaching a class.

“I was hooked the minute I saw her teaching,” he states simply. “That was it.” He enrolled in her class, and came down every week to hear her lecture. He was still holding his job with the Budget Bureau, and one day, after he’d been studying with Miss LeGallienne for some time, she called him over. He’d come to class late, as usual.

“Why are you always late?” she asked.

“I have to drive down from Hartford.”

“But there are no theaters in Hartford,” Miss LeGallienne said.

“Oh, I’m no actor,” he explained.

She looked at him for a long moment, and said,

“You should be.”

Peter had found himself. He had found something he loved, and he could stop running now, stop searching.

His next thought was Alice.

“I’m going to New York,” he told her, “and I’m going to become an actor. A good actor.” And for some strange reason, as crazy as it sounded, she knew it would be just as he said. She went with him, and they were married.

After several successful TV appearances, Peter landed the now-famous role in “Murder, Inc.” The little kid with the big dreams had made good. The future looks bright for Peter Falk now. He’s on his way, and nothing can stop him. Nothing’s too hard or too tough for him to conquer. After all, he fought the toughest battle of his life when he was eleven years old. He fought then—and won. Now he can fight anything and come out on top.

THE END

—BY CHARLES MIRON

Peter’s in U-A’s “Pocketful of Miracles.”

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE MAY 1961

zoritoler imol

2 Ağustos 2023Very interesting topic, regards for posting.