So Nice To Come Home To—Jeff Hunter

Long distance couldn’t have taken much longer. Finally, after what seemed like a couple of eighty-second minutes, the operator reached Santa Barbara. “Hello, mother,” said my brand-new wife. “Mother . . . I’m married.”

Naturally I was concerned when I saw Barbara’s face grow solemn. I was even more concerned when she held the receiver out toward me and I could hear nothing except a heavy, dead silence.

AUDIO BOOK

“Why doesn’t she say something?” I asked Barbara.

“She said something, Hank,” came my bride’s solemn voice.

“Well, what, for instance?”

“She said, ‘Oh, no!’”

As a bachelor, I’d always maintained that there was nothing like a fellow getting of! on the right foot with his mother-in-law. However, when I faced the problem as a bridegroom, I found myself feeling as if I had two right feet. “Hank,” now Barbara was grinning and handing me the phone. “She wants to talk to you.”

I brightened considerably. All was not lost. At least Mrs. Rush was still speaking to me. This lovely lady had helped us plan our wedding—the one that was to have been a formal church ceremony, the kind all mothers dream of for their daughters. But, while movies encourage romance, picture schedules seldom stand still for details like ceremonies and honeymoons. Although Barbara and I had set a fairly definite date some time before, neither of us was certain we’d be able to keep it. So, on the spur of the moment one evening, we decided to elope. “I know you’re disappointed, Mrs. Rush. . . .” I began to stammer.

“Of course, I am, son-—a little, I must admit,” she said. “But not enough for it to really matter.”

She was telling me not to worry about a thing when suddenly it dawned on me that she’d called me “son.” Just as suddenly, I was calling her “mother.” Today, when I happen to mention that a man’s best friend is his mother-in-law, some people look at me as if they’re convinced I’m compiling a joke book. Or have lost at least part of my mind. Then I either explain, which takes a little time—or introduce her, which ends the discussion in nothing flat. In the latter case, results are predictable. Almost immediately, even the worst skeptics are calling her “Mother Rush.”

“That situation of yours is unique ” a buddy of mine once said.

Unique it may be or may not be. But of one thing I’m sure: It’s wonderful! I’ve no reservations about telling the world that we’d find it pretty difficult to live without Mother Rush.

Our marriage wasn’t terribly old before I realized that my wife had a gem of a parent. Barbara and I had decided to go in for housekeeping in a large way. And the house we found was ideal for such a venture. Large. The two of us rattled around in it for seven days before I had to leave on a location trip. It was here that I left my bride—amid stacks of boxes, tons of tissue paper (all of which had to do with a multitude of wedding presents) and a good many possessions that I’d accumulated during my bachelor years.

I returned three months later to find order where there had been chaos. You’ve never seen such order. Everything was in its place. Even if Barbara hadn’t been working days and coming home tired at night, this would have been a major project. “You’re wonderful,” I said, glancing around me.

“You might as well know—it’s Mother who’s so wonderful,” said Barbara. “I was lost. But she came in and . . . .”

Mother Rush had promptly turned one of the bedrooms into a utility room. Therein were neat piles of ski equipment, camera equipment, and the rest of my worldly belongings which had no place in the living room, dining room, and hallways. She seemed slightly surprised the tenth time I thanked her.

“I felt a little funny sorting out your things,” she told me. “And I didn’t want to throw anything away. That’s something you can do, if you like.”

“You should have seen her when she found your old letters,” Barbara grinned. “She wouldn’t even straighten them. Just pushed them all together and put them in the closet.”

M other Rush always seemed to appear when we needed her . . . when we moved into a small apartment, when we moved into a larger apartment in Westwood, and, most importantly, when Chris was born. She and I sat in the hospital waiting room together. We didn’t say a word. We thumbed through magazines. We didn’t read a word. Every so often she’d smile reassuringly. And, to me, that meant more than a million words. When I got my first glimpse at the contents of the small blue bundle held by the nurse, I guess I was like any new father. Floored.

“It’s a baby,” said Mother Rush helpfully. “He’s a lovely baby.”

“Is he?” I kept babbling. “Is he really all right?”

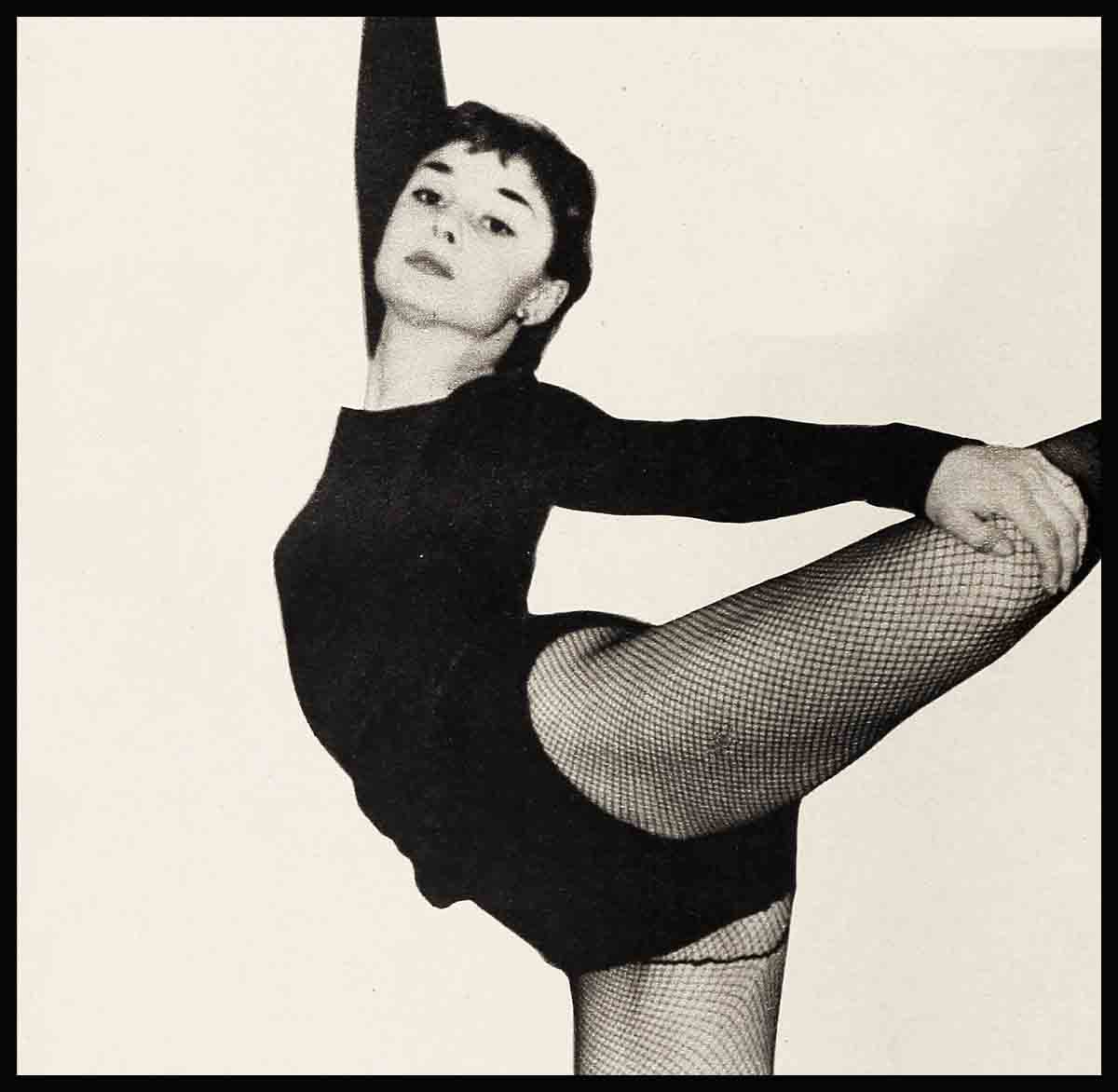

With Chris’ arrival, we found ourselves facing a serious problem—Barbara’s career. Her work is of prime importance to both of us, for we believe that marriage and careers do mix—and well. And there was a contract waiting for her at Universal- International. At U-I when you’re not making a picture, you’re taking lessons—singing, dancing, and dramatics. We’d talked about it many times. “Of course, we can find some fine person to take care of the baby,” Barbara said hopefully.

“A very capable person,” I helped her hope.

“Can we find someone permanent?”

“Well, if she ever has to leave, we can get someone else . . . .”

“Hank, a succession of nurses might give the baby a terrible feeling of insecurity . . . .”

“Hmmm—and they’d all be strangers . . . .”

That’s when Mother Rush and Barbara’s sister, Ramona, moved into an apartment about a block away from our own. Since then, Mother Rush has been taking care of us all—full time.

Problems? We have our share. However, they never seem to conform to the joke- book pattern. Take the one about the mother-in-law who minds everyone’s business except her own. Mother Rush goes straight to the other extreme—especially when it comes to telephone messages. Here’s where we’ve had to ask her to be more inquisitive.

We’ll come home and find a stack of names on the pad. “What did they want?” we ask her.

“I thought you’d know,” is her reply. “I hate to question them when it seems to be none of my business.”

A crisis? A couple of them. At one point, Mother Rush headed for the front door—and what loked like a final farewell. You see, I’m a great one for gadgets. I spot one and it’s bought—no matter what it’s meant to do. The trouble came one Thanksgiving, when I explained to Mother Rush that once she’d mashed the potatoes in the new mixer I’d brought home, she would never do it by hand. It was her first try. Result: Whipped potatoes on the kitchen walls.

In preparing the turkey, she tackled the special roasting device I’d discovered. She’d always used an oven, but I was enthusiastic and she was game. However, I neglected to mention that there was a trick to lifting the turkey out of the roaster. Result: one turkey on floor.

The dishwasher was the final straw. She was used to her own and didn’t realize that ours took a special brand of soap. Result: a batch of flying soapsuds. With this, Mother Rush stalked out of the kitchen, “I have ruined the dishwasher,” she announced. “It’s gone. I’m gone. At least I’m going. You won’t have to ask me to leave.”

Result: one son-in-law jumping up to bolt the door. And a few basic demonstrations in the Hunter kitchen.

Everyone has his own ideas on bringing up children. However, we’ve taken quite a few lessons from Mother Rush’s book, sometimes without even realizing it until much later. Barbara and I have collected a number of volumes concerning the care and raising of little ones. And we’ve tried to follow their advice. One important thing most of them tell you is never to say “No!” to a child. You’re supposed to simply direct his interest to something else.

My mother-in-law silently went along with the theory. Then came the day Chris climbed up on the couch and reached for the knick-knack shelves. He was intent upon pulling them off the wall and his interest refused to be directed elsewhere. After a while, I resorted to saying “No.” Several times. Then I spanked his hand. Chris got hysterical. He laughed so hard he nearly fell off the couch. But—with patience—Mother Rush convinced him that it was no laughing matter. Now he knows that “No” is a word that should be respected. Since then, we’ve been combining psychology with a bit of the good old- fashioned way of bringing up children.

Mother Rush vows that our child is a great conversationalist. She and he have long talks, and they seem to understand each other perfectly. Barbara and I have decided that they have a language all their own. We came home one night and found Mother Rush beaming. “Wait till you hear Chris,” she said, proud as punch.

We looked at Chris. I guess we expected him to break into a recitation of the Declaration of Independence. Mother Rush’s expression left little doubt in our minds. Chris looked at us. “Ca,” he said.

“Ca?” said Barbara.

“Ca?” I repeated, hoping for a clue.

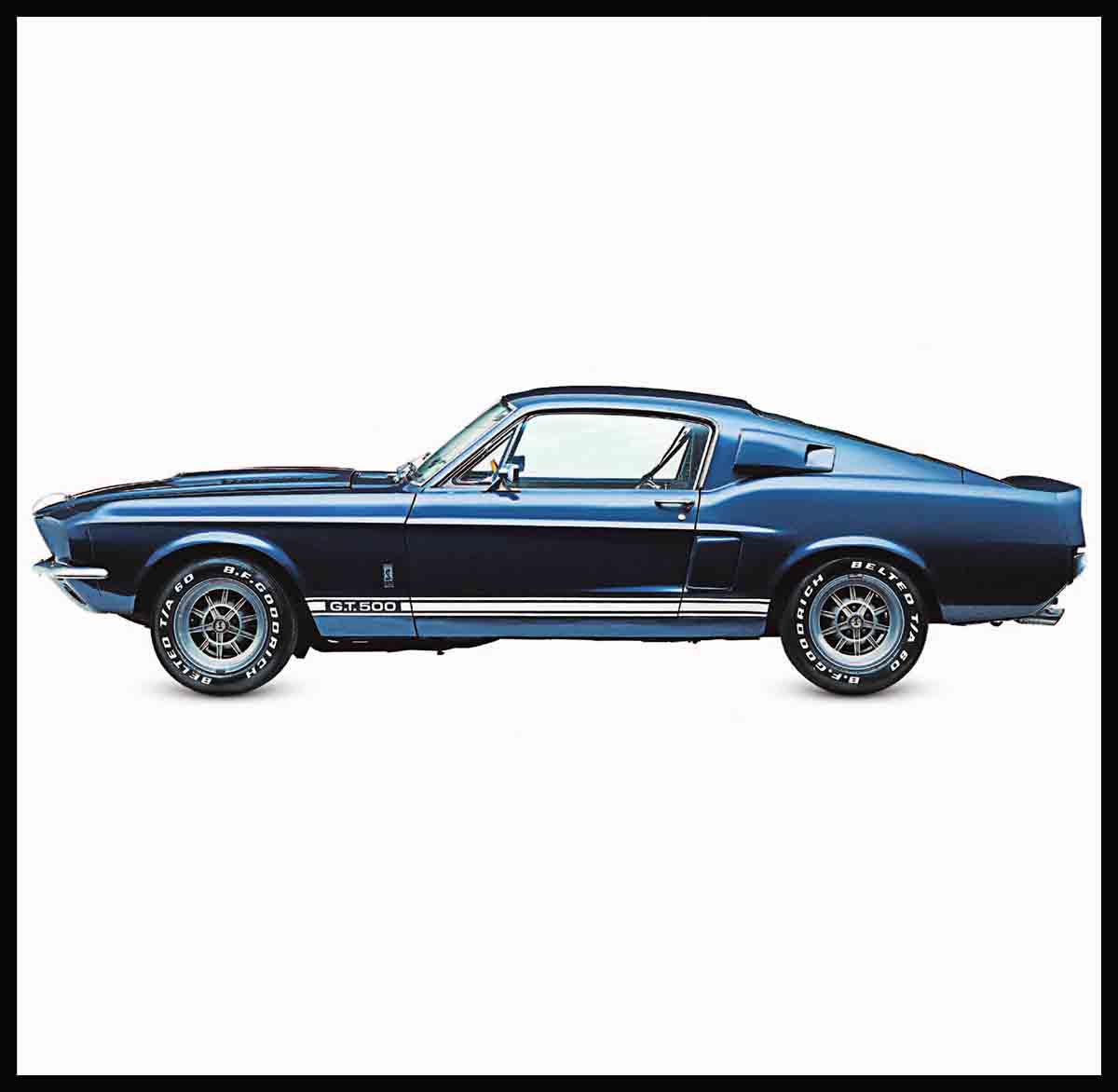

“Your son is saying ‘Car,’ of course,” said Mother Rush icily. “Anyone would know that.” And she still thinks so.

When it comes to raving about our son, Barbara and I stick to our guns. We’ve always vowed that we’d avoid going on for hours about how cute or clever he might be. But when other couples begin on their small fry, we can always manage to bring out a few dozen photographs. However, we can count on Mother Rush’s knowing smile to check us when we go overboard.

Actually, she has no hard and fast rules about raising children—or about how we should conduct our lives. “It’s your life,” she’ll say. “All young people have their ups and downs. But there are no such things as real mistakes—only experience. And that’s how you learn to work things out for yourselves.”

She knows very little about the movie industry. She’s never tried to offer any advice regarding our careers. And we’ve taken our cue from Mother Rush as far as Chris’ upbringing is concerned. “In a family, if the parents stand for the best there is, things will come out accordingly,” she’s told us. “If there’s been a good family relationship, it will show up when the child is on his own. Give him a basic philosophy and teach him to use his own mind.”

It’s something to remember. Barbara and I are both from happy homes. That’s why we believe we have a solid foundation for marriage. And now we have roots—a house of our own. It boasts three bedrooms and a den. And outside there’s a large play area for Chris. Nearby, there’s a small guest house, where Ramona and Mother Rush have set up housekeeping. Mother Rush thinks it’s great for all of us. When she first saw it, she uttered some mighty thoughtful words. “I’m glad we’re together, but it’s necessary to be separated, too. I want you to feel you have your homelife to yourselves. And remember that!”

Life with mother-in-law goes on as usual. When Barbara and I are working, Mother Rush slips over at the crack of dawn to feed Chris and make the coffee. She takes care of him until we come home. She cleans the house, manages to see that our clothes are without wrinkles, and now takes telephone messages like a first-rate secretary. It’s little wonder Barbara and I never laugh at the story of the husband who tells his wife, “If we ever argue, dear, I’ll go home to Mother—your mother.”

But I know that we’ll both be going home to Mother Rush quite often. Together, of course!

(Jeff is in “Three Young Texans”; Barbara is in “Magnificent Obsession”)

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE MARCH 1954

AUDIO BOOOK

zoritoler imol

2 Ağustos 2023Well I definitely enjoyed studying it. This post offered by you is very effective for accurate planning.