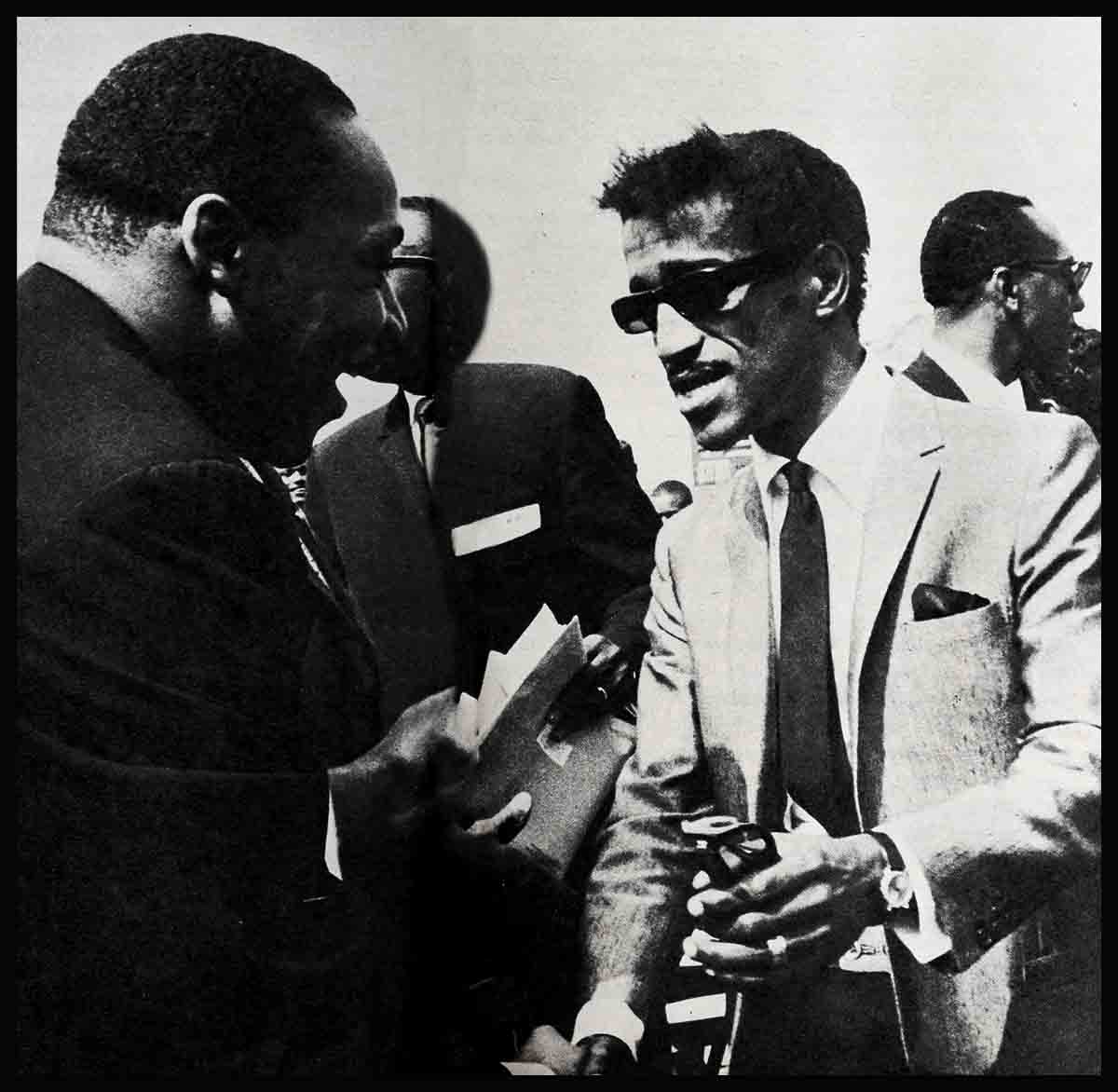

How Two Negro Showmen Fight For Integration—Sammy Davis, Jr. & Dick Gregory

Even the lone American Nazi picketing outside Los Angeles’ Wrigley Field (his sign read: “To Mix Races Is Jewish”) must have been impressed by the roars of approval coming from the crowd of 35,000 Negroes and whites at the freedom rally. That crowd included May Britt, Dorothy Dandridge, Mel Ferrer, Tony Franciosa, Rita Moreno, Paul Newman and Joanne Woodward. They were applauding the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., leader of the Alabama “Non-Violent” desegregation movement, as he declared, “We want to be free whether we’re in Birmingham or in Los Angeles.” And they were applauding actor-singer Sammy Davis, Jr., who embraced Dr. King and presented him with his own personal check for $20,000—a week’s salary from his Las Vegas engagement—in support of the “Freedom Rally for Birmingham,” and told the audience, “This should prove to you good people once and for all that my leader is your leader!” They were also applauding Negro comic Dick Gregory, who sparked shouts and laughter when he said, “I can’t tell you what a pleasure it is being back in a mob again. . . . You know, you people are looking at a convict.”

The crowd was heralding Dr. King as the personification of its ideal of freedom and human dignity. In applauding both Davis and Gregory they were acknowledging that it is possible for two radically different men from completely dissimilar backgrounds to use almost opposite methods in reaching a common goal: the social, political and economic emancipation of the Negro people. It was the same goal.

When Sammy said, “This should prove to you good people once and for all that my leader is your leader,” the emotion in his voice gave the impression that he was a man who had been criticized—in his opinion unjustly—and now he was publicly replying to it.

There had been criticism, lots of it. The anti-Davis sniping had come to. a head when Sammy was in London, just before the rally, when reports had trickled back to America that he’d said he was going to become a British citizen one day. That came as a shock to many.

“Running away when the going gets tough,” some of the leaders of the integration movement concluded; and they were quick to make a comparison between Davis and Gregory: at the very time that Sammy was “giving up” the fight, Dick had cancelled his nightclub engagements to join his fellow Negroes in braving snarling police dogs in Greenwood, Mississippi, and club-wielding cops in Birmingham, Alabama.

But the comparison was made without having all the facts.

What actually happened to Sammy in London?

Well, Sammy did say that he plans to live in England with his wife May and their children, because “Here, there is freedom.” Sammy did tell reporters that he dreams of an English country house with flowers and friends around him, and he did offer to buy the period estate of John Mills, Hayley’s dad.

This was just after an unprecedented reception Sammy received for his one-man show on BBC-TV. When the program ran overtime, the switchboard at the studio was lit up by calls from Britishers who usually insist on punctuality but who were now insisting on unpunctuality and threatening to boycott the station if Davis were cut off before he was finished. He was a solid hit.

Sammy himself said, “I regard that show on Sunday night as the best TV work I’ve ever done here or anywhere else—and that includes back home, too. There was a tremendous spirit of cooperation and warmth and sympathy between every single member of the crew and it gave me the kind of incentive—a kind of lift-off—that I’ve never experienced before. I want to work in that kind of atmosphere again; I want to work in Britain a lot more.”

But expressing a desire to live in England six months of the year, and scouring around for a house, and praising British freedom and flipping with joy because of the reception given to a TV show are not the same as saying you’re going to put America out of your life and become a British citizen. What Sammy did say, while appearing in Scotland, is, “I want to learn to act in a little theater, and Glasgow’s Citizens’ Theater seems to be just what I am looking for. It’s something you just cannot do in the States. I don’t care how small the part is or how much they pay me.” If he’d say something like this in Hollywood, he went on, people would figure he was washed up.

What he did say was that he was sold on life in London after hearing a six-year-old boy call his father “Sir.” “I want my children educated where that sort of thing can rub off on them.”

What he did do was sign a three-year pact with BBC-TV under the terms of which he will do a minimum of six forty-five or sixty-minute shows, all live, at about $12,000 an appearance (far below his usual fee). He really dug England!

No escape

But to maintain, as some of his detractors in America did, that Sammy was fleeing to Britain to escape from the fact that he is a Negro—this charge was pure nonsense. Just the opposite: Sammy made a point of leaving his wife back in the States and explained. “I didn’t want her to undergo the same humiliating experience again.”

He was referring, of course, to the last time he had been in London, when May was with him. That’s when Sir Oswald Moseley’s storm-troopers had chanted. “Mixed Marriages Are Taboo—We Don’t Want A Negro Jew”; and that’s when Sammy had broken down and cried, “I never expected to see it in England. This could never have happened in the United States unless, maybe, in the South, like Mississippi.”

And even this time, a vicious attack was made against Sammy. Sir Gerald Nabarro said. “It is black versus white. If anyone disagrees with me, I say to them: Would you be happy if your blond, blue-eyed daughter came home with a buck nigger and said she wanted to marry him?” (When Sir Gerald went on to rail against the prospect of “coffee-colored grandchildren,” the association was clear: May Britt was the “blond, blue-eyed” woman, Sammy Davis was the “buck nigger.” and the “coffee-colored grandchildren” would be their children’s children.)

Sammy was asked for his reaction to the attack. His reply was calm, reasonable. devoid of personal venom.

“The race problem is very much there with every Negro. But I joke about it, because it is always better to joke about things like this. That way you do what you can to improve the situation. As soon as you ridicule something, laugh at something, it gets easier. This is the great democratic way of dealing with any serious moral issue.

“I respect the American Southerner who fights for what he believes in. But I have no use for the bigot, the extremist on either side. The word “nigger’ is rotten and stinks to high heaven, whoever uses it. It is impossible to hope to be accepted as an equal in any town if you are colored. And I say that from the most advantageous point of view.

“Here I am, a success. Doors are open to me, or to any successful Negro, that are closed to the average guy. You try each time to create as much good will as you can.

“Sometimes they say, ‘Gee, he was nice.’ And that makes it just that little bit easier for the next guy. . . . I mean the next colored guy.”

After Sammy made this statement Sir Gerald backed down. “I did not mean to be offensive—only complimentary,” he said. “Nigger was used instead of Negro, and buck was used in the sense of conveying masculinity.”

But extremists in the United States, many of them members of Sammy’s own race, were unaware of the attack and Davis’ counter-statement. They spread the new lie that Sammy was “running away when the going gets tough,” and they dredged up the old charges that Davis’ conversion to Judaism had been just a publicity stunt and that his being buddy-buddy with Sinatra and the Clan and his marriage to May Britt proved that he was anti-Negro and actually wanted to be white.

Far away and long ago, Sammy answered all these charges—by his words and through his actions.

To the charge that he became a Jew just to get publicity, he replied softly, “Inside of every man there is a need to try to reach God in his own way. . . . I did not change to Judaism because any of my friends influenced me, although some people say, ‘He’s around Jews so much he wanted to be a Jew.’ The thing that I found in Judaism that appealed to me is that it teaches justice for everyone. . . . There’s an affinity between the Jew and the Negro because they’ve both been oppressed for centuries.”

To the charge that he married May Britt because he was anti-Negro and pro-white, he replied simply, “We fell in love,” and let others make lengthier statements. Others like Negro singer Eartha Kitt who, when taunted by her own people for marrying a white man, accused her attackers of advocating “reverse racism.” “Those people are angry at me because I am married to a white man,” she said, “but being married to a white man doesn’t make me less a Negro or a fighter for civil rights.”

To which Sammy would have added a sincerely heartfelt “A-men!”

For all Gregory cares

(It is to Dick Gregory’s credit that he has come strongly to Sammy’s defense in this matter. When people ask him what he thinks about Sammy and May’s marriage, he answers: “For all I care, Sammy Davis could have married a grizzly bear. I couldn’t care less who anyone in this room married. If two people are in love that’s their business.” . . . In his night club act he sometimes defines a Southern bigot as “a person who thinks Mr. and Mrs. Sammy Davis are just about the nicest couple ever—if it wasn’t for him.” . . . When Negroes ask him, “Would you want your sister to marry a white man?” he sometimes snaps back: “She married a dope addict the first time, but I didn’t object. I would leave that up to her.” And at other times he replies: “I wouldn’t care, but her husband would raise hell.” . . . His definitive statement on the problem is contained in the statement: “They wanted me to volunteer for the space program, but I turned them down. Wouldn’t it be wild if I landed on Mars and a cat walked up to me with twenty-seven heads, fifty-nine jaws, nineteen lips, forty-seven legs and said, ‘I don’t want you marrying my daughter neither!’ ”)

To the charge that he’s buddy-buddy with Sinatra and the Clan because he really wants to be a white man—and to the accusation that he’s anti-Negro, Sammy stated: “If I hire anyone who isn’t a Negro to work for me. I’m anti-Negro. . . . The most prejudiced people in the world are the oppressed. They have no other way to fight back, so they fight prejudice with prejudice. . . . I have no desire to be a martyr. I know I’m a Negro. I’ve never forgotten it. How can I, when I look in the mirror every morning? But I’m ready to fight for my right to pick my own friends.”

Sammy’s friends happen to be Frank Sinatra and Dean Martin and Joey Bishop, with whom he holds “Summit Meetings” on stage. “Frankly, I’d like to do it with some other guys,” he says. “I’m open any time Billy Daniels, Billy Eckstein, Nat Cole say, ‘Let’s get together and do a Summit Meeting.’ ”. . .

Dick Gregory, meantime, was aiding the same struggle in his own way. He flew to Greenwood, Mississippi, in the heart of Leflore County where 95.5 per cent of the 10,274 whites of voting age are registered and only 1.9 per cent of the 13,567 Negroes are allowed to vote. Gregory joined with members of his race who walked two-by-two towards the court house in an attempt to register. Snarling police dogs and club-wielding cops blocked their path—and they never got there.

Four times Dick led marches on the court house, and four times he and his group were stopped. But they could not stop him from talking.

“There’s your story,” he told reporters, pointing to a phalanx of impassive cops. “Guns and sticks for old women who want to register. There they are—illiterate whites who couldn’t even pass the test themselves. That’s what you see, guns and sticks in America.”

Gregory’s arm was twisted by one policeman, he was clubbed in the back by another, but, because he was a celebrity, he was given “special” treatment and not arrested.

At the end of four days Dick left Greenwood. Local officials had agreed to furnish a bus in which Negroes could ride to the court house to register. “When you get the white man to furnish Negroes a bus to register to vote and you can ride up front,” Gregory said, “then you know you have won.”

But the struggle for human dignity is a struggle that must be fought over and over again. There had been the University of Mississippi and James Meredith, for example. (“I worked a show in Jackson, Mississippi,” Dick explains. “I arrived in town late, Meredith had just left, but I got his phone number. We talked on the phone several times and I asked him if be wanted to come up to Chicago for Thanksgiving. He said he would, and he came up and this is when we really got tight.”)

“Getting tight” is an expression for getting to know somebody very well. It was in Chicago that Meredith told him he wanted to go back to the University for the second semester, despite the fact that he had been harassed and hounded constantly—like receiving a poem from a classmate which read: “Roses are red, violets are blue; I’ve killed one nigger and might as well make it two.”

Meredith’s courage was strengthened.

As columnist Leonard Lyons put it, “James Meredith’s decision to stay at Ole Miss was influenced by Dick Gregory, his good friend. Gregory flew to Oxford, Mississippi, last week, and spent a full day persuading Meredith not to leave the University.” Certainly a labor of love!

Humor for troubled times

Dick Gregory spoke with humor—to soften the situation, to point up the absurdity of differences in skin-color dividing Americans: ‘The funny thing about the University of Mississippi-James H. Meredith problem is that it took sixteen thousand soldiers to put a man in school. It’s probably the first time in the history of the world that an army joined a man. . . . Then the U.S. marshals had to stay so close to Meredith that they made better grades than he did. And one thing for sure—Meredith didn’t get the exam answers from the other kids.”

And for Dick Gregory there was also Birmingham.

Birmingham had been in the throes of a small civil war for twenty-nine days. Police Commissioner Eugene (“Bull”) Connor had sent club-wielding cops against Negro children and vicious police dogs against Negro adults. (“I want ’em to see the dogs work,” Bull shouted to his officers. “Look at those niggers run.”) On the thirtieth day Dick Gregory was in Birmingham and, coincidentally, the tide turned.

“I didn’t do much down there,” Dick says. “An hour and a half after I arrived, I was in jail.” (He was arrested when he marched at the head of a group of eight-hundred children protesting segregation.)

“Bull Connor told me to watch it, or he’d give me a white eye,” Dick now quips. “I said if that was the case, then he’d be doing me a favor by hitting me all over.”

Shortly after he was released from jail, following four days of imprisonment, he showed reporters the welts and bruises on his arms. He called his jail term the “most miserable experience of my life” and said “I was hit all over, including about the face” by five cops “using billie clubs, hammers and sawed-off pool sticks. I remained as much nonviolent as I could and didn’t fight back. You leave the world when you go into the Birmingham jail.

“I never wanted to go to jail. But I’ve never been so glad as when I saw the spirit of those kids.”

Later, when his injuries had been given medical attention, Gregory was able to salvage some humor from his experience. “It wasn’t bad in jail there in Birmingham,” he said ruefully. “There were five hundred in a cell designed for fifty. Sort of wall-to-wall us. You can get used to Southern jail food. The first day the food is slop, the second day it’s garbage, the third it seems like home cooking, and by the fourth you’re asking for the recipe.”

Today, almost as an afterthought, he says, “If there’s more trouble and I can be of any help, I’ll go back. It’s something a man has to decide for himself.”

Two different ways

It’s something a man has to decide for himself—how best to fight for human dignity; and yet, to a large degree, Dick Gregory’s and Sammy Davis’ different ways of aiding the struggles of the Negro people were decided by their own early experiences.

From the age of three, when he first toddled out on stage as part of a family act, Sammy has known applause (and at least partial acceptance) from the white world. On the Orpheum Circuit and, when he grew older, in burlesque, the other performers, white and black, made him feel at home.

The stage was his home. And any special feelings he might have had about being colored disappeared after Frank Sinatra became his friend and convinced him he could be more than just another hoofer—that he had the talent to become a singer and a comedian and an actor, too.

But more than that, it was Frank’s no-nonsense actions towards bigots that made Sammy feel that here was a true friend: in Boston, when a radio engineer slurred a Jewish musician, Sinatra cracked him with a bottle; and when a counterman in a diner refused to serve a Negro, Sinatra hauled off and slugged him. Says Sammy, “Frank helped me overcome my greatest handicap, my inferiority complex about being a Negro.”

Dick Gregory, on the contrary, has always been an outsider to the white world. (Recently when he was being interviewed backstage at Harlem’s Apollo Theater, he said flatly and sadly, “I have never had a white friend”)

As a child in depression-ridden St. Louis (he was one of six children), the only way he was able to handle the white world was to run from it, fight against it or try to laugh at it.

One of Dick’s earliest memories is of the first time he struck back at white injustice. “I was shining shoes—I was six years old—and they were calling me ‘nigger,’ ‘shine,’ ‘monkey’ and everybody was participating in it until this one white guy kicked me in the mouth. Then the fight started—because at this point I quit being a ‘nigger,’ I quit being a ‘shine’ and I quit being a ‘monkey’ and I turned into a kid. But the guy kicked me and this was when the fight was on—this was when I became human.”

Sometimes when you’re colored you fight—and sometimes, because you’re colored and poor, you run. “When I was seven my father went out for a paper. . . . He ain’t been back since. When I found out I was poor and on relief, I was so ashamed I wouldn’t walk in the streets when my mother sent me out for a loaf of bread; I ran a mile through the alleys to reach the store two blocks away. Didn’t want anybody to see me. It gave me good legs.”

And sometimes when you’re a Negro and you’re surrounded by bullies, colored or white, and they’re picking on you because your hand-me-down clothes are funny and your father has cut out and not come back and your body is skinny and undernourished, you can’t run and you can’t fight. That’s when you discover that if you pick on yourself, laugh at yourself, they’ll quit picking on you and start laughing at you—and then with you. (“Once I got them laughing,” Dick recalls today, “I could say anything”)

So sometimes you run and sometimes you fight, but always you laugh—even when it hurts; and then, somehow, it doesn’t hurt quite as much.

Dick went from an all-Negro grammar school to an all-Negro high school. Naturally enough, he became a championship runner on the track team. But, inasmuch as the Missouri sports program was not integrated, his running records were not given official recognition. That bugged him.

“When school was out,” he recalls, “I set up a march on city hall. I just wanted our records recognized, but I had to say we were marching against overcrowded schools. It made national news and they said the whole thing was Communist-inspired. But the city officials were so ashamed they integrated the track meets right away. And I said to my boys: ‘Let’s run the hell out of ’em,’ and we did. And the next year St. Louis integrated all the public schools without waiting for the Supreme Court decision.”

He got a track scholarship to Southern Illinois U (technically integrated, actually segregated), “but Carbondale, Illinois, wasn’t much better than Greenwood, Mississippi, then, despite a governor named Adlai Stevenson.” Negroes were forced to sit up in the “peanut gallery” at the movies, but he helped break that down.

Surviving the Army

For both Dick and Sammy, service in the United States Army crystallized their attitudes towards themselves and the world.

Sammy, for whom the world up to that time had been the stage, where he had received acceptance from white audiences and white performers, discovered in military service what Dick had known all his life—that it’s hell to be a Negro.

As Sammy told reporter Pete Martin: “My first day in the Army I found myself in a unit composed of seventy white fellows and one colored. The other colored boy was an appeaser. He always said yes, sir, and no, sir—not just to the officers but to the enlisted men. I thought him an Uncle Tom, a role I never intended to play. I was standing in line in the washroom, waiting to get to the sink, when one of the white fellows grabbed me by the back of the T shirt and pulled me away. ‘What’s that for?’ I asked, and he said, ‘Where I come from, niggers stand in the back of the line, behind the white people.’ I took the little bag in which I carried my toilet articles and I hit him in the mouth with it and knocked him down. I’ll remember what happened next if I live to be a million. He looked up at me, wiped the blood from his mouth and said, ‘But you’re still a nigger.’ From that moment I decided that the only way to fight was with what intelligence and talent God has given me. Sometimes it works.”

Dick Gregory also discovered while in the Army that you can’t fight the whole world all the time, and that sometimes it’s even more effective to use talent than force. His talent, of course, was his ability to ridicule prejudice—his own and others. He was able to say—and make Southern white soldiers laugh at him and at themselves when he said it: “If I can go to the four corners of the earth to lie on the cold ground and shoot at a man I’ve never seen in order to guarantee certain rights to a foreigner, then there is something wrong with me if I don’t fight for those same rights in Mississippi.”

Today, when some drunk in a night club yells “nigger” at Gregory, he doesn’t hit back with his fists, as he did years ago when he was six, but calmly says, “According to my contract, the management pays me fifty bucks every time someone calls me that. So will you all do me a favor and stand up and say it again—in unison?”

Today, when some member of the audience gives Davis a hard time, he doesn’t try to poke him, as he did back in the army when he was seventeen. “The other night there was a guy sitting ringside,” he says, “looking at me with sheer, naked hatred in his face. I gave my whole show something extra because I wanted to get him. and finally I did. I heard him turn to his friends and say, ‘I don’t care what anybody says, I say this guy’s okay.’ That’s the only way I can fight.”

The goal is dignity

Different roads; different methods; the same goal. Human dignity.

“I think Dr. King’s nonviolent movement is the only movement in the South.”

Who says that? Dick Gregory, who participated in the nonviolent movement in Birmingham.

“We need only about twenty-five more men like Martin Luther King, on both sides of the color spectrum, and this thing would be over. I’m disgusted with extremists on both sides of the racial question. They just inflame people. Just to talk to Martin Luther King is a thrill. He’s the Ghandi of the human race.”

Who says that? Sammy Davis, who had done benefit after benefit for Dr. King and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference and has contributed many thousands of dollars to the cause.

The last word? How about Sammy, quoting the advice his father gave him long ago? “Sammy, you must always judge a person as he is. It is the worst mistake a Negro, or a white man. can make—to judge—no—to pre-judge. The color of a man’s skin has nothing whatsoever to do with what is in his heart.”

Or perhaps the last word should be Dick’s. Just after he came back from taking part in the voter registration struggle in Greenwood. Mississippi, he painted this picture of what had happened.

“We’re marching toward the court house. We pass maybe five hundred people on one street corner and nobody says go home. I look in their faces and I see no hate. I see faces looking at a parade. Faces interested in what’s going on, like watching a missile test, and maybe hoping nobody gets hurt. The only name-calling came from the police. And maybe that was more ignorance than hate.

“What we did have, there in that little Mississippi town, was white people who gave us pencils and paper along the march, so we could write what was happening to us. And a car would come by, in the late evening, and a white hand would reach out and give a Negro man or woman some tobacco or snuff, or an article of clothing. There were moments when you thought the gulf between us was not so great.

“As one man said in our meeting the last night, we don’t want to outrun the white man, and we don’t want to walk ahead—we just want to go down the street together, if we happen to be going at the same time.

“When the Negro’s house is on fire, man, and those white cats get in there, I don’t think they go any slower to get to the Negro area to put the fire out than they do in a white area; they go in and they take a chance on losing their lives—they’ll go in through that window and pull those kids out and you only go back to being a Negro when you enter that hospital. But while they are getting you out of that building, you are human.”

Or, Dick might have said, they don’t go any slower to get to a Negro’s house when they’re trying to save the life of a child who’s gasping for breath and for life itself. For when Dick was demonstrating in the South, white men, firemen, were at his home in Chicago doing everything possible to save the life of his son, two-and-a-half-month old Richard Claxton, Jr. Dick’s wife had called the fire department when she discovered that her son was having difficulty breathing. The firemen arrived quickly and administered oxygen to the child. To them he wasn’t a black youngster or a white youngster, but just a kid in desperate trouble. But despite all their efforts, Richard died on the way to the hospital.

After flying home for the funeral. Dick Gregory returned to Jackson. He had to. For the sake of his dead son. For the sake of his two daughters, Michelle and Lynn, and of his wife. For the sake of his own manhood, his own conscience. And for the sake of kids everywhere, white and black, who, though alive, were dying a little because of the venom of race hatred.

THE END

—BY JIM HOFFMAN

Sammy’s in “Three-Penny Opera,” Embassy. Hear him, too, on Reprise records.

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE OCTOBER 1963