Kim Novak With The Lavender Life

WHAT HAS GONE BEFORE: In Part I of this stranger-than-fiction story, George Scullin described Kim Novak’s early days in Hollywood and how she was catapulted to stardom. He also told how, throughout the fantastic dream she has been living, Kim has perpetually had to fight uncertainty and bewilderment—which, in itself, is a prelude to learning what makes this amazing girl tick.

Last summer, the dazzling Kim Novak returned from her triumphant tour of Europe to find herself confronted with two of the choicest roles in Hollywood. One would co-star her with no less than Rita Hayworth and Frank Sinatra in a lavish musical production, “Pal Joey.” The other would give her the title role in the highly dramatic film version of “The Jeanne Eagels Story.” The latter assignment left Kim excited, but more than a little bewildered.

“Just who,” she asked, “was Jeanne Eagels?”

That is the kind of question that might stamp any other actress as a “dumb blonde,” but not Kim Novak. This exceptionally forthright young woman, disdaining to pretend a knowledge she does not possess, is a firm believer in asking honest questions and getting honest answers. It is one of her most valuable assets. and her questions about a picture usually end with her being the best informed member of the cast.

So swiftly has Miss Novak skyrocketed to fame, and so alluring and regal is she in all her glamorous photographs, that a myth has been created to the effect that she is too beautiful to have to work. Quite the opposite is true. Within two months after getting the Jeanne Eagels assignment, Kim not only knew all about the tempestuous actress as she would appear in the picture, but she was an authority on every phase of Miss Eagels’ life. How does she do it?

“I’ve read everything I an find on Miss Eagels,” she explains intently. “I found several of the books myself. I’ve put my friends to work digging up more, and several authorities on the theatre are helping me track down old magazine articles. As I read, I mark down passages that will help me understand the script, and then I have these passages typed out. Next I put them in order, like this.”

She held out some hundred pages of typewritten notes. “I’ve almost got a book—my own book—so I don’t have to hunt through all the other books and magazines to find the passage I want. The way I have it arranged, these pages follow the script, so every time I get ready for a scene, I’ll have all my background material right at hand.”

That may sound more like the academic drudgery of a bookworm than the glamorous life of a movie queen, but for Kim it was only the beginning. She dug out films made by Miss Eagels that even her own studio thought to be out of existence. She has studied by the hour every move of Miss Eagels’ hands, her facial expressions, her seductive walk, her unique, exotic technique of screen lovemaking, and her regal way of wearing clothes. In the same manner Kim has listened to sound tracks of Miss Eagels’ voice. There are but two in existence, because Miss Eagels died in 1929, after one of the most brilliant and stormy careers in show business history.

This ability to concentrate and lose herself in her work dates back to Kim’s childhood in Chicago. She was shy, self-conscious and ill at ease to the point of awkwardness with strangers. But, contrary to most stories that picture her as a skinny, bony-kneed, flap-wristed object of ridicule, Kim was as beautiful as a child as she is today. And, far from making fun of her, boys used to stand in line just to show off in front of her. Unfortunately, this homage only served to make Kim more self-conscious, and she would spend long hours of solitude reading in her room rather than face the strain of being the center of attention.

Out of her frequent solitude grew a vivid imagination, and out of her imagination grew a dream girl who was neither shy nor self-conscious. This dream girl could act, sing, dance, flirt with boys, model beautiful silks and sables, and win the Miss America contest every year forever. She was quite a girl, and Kim—she was Marilyn Novak then—loved her. By the time she was eleven, Kim could become this dream girl at will.

And it was when she was eleven that she met Norma Kasell, the girl who, more than anyone else, started Miss Novak on the road to fame. At that time Miss Kasell was employed in the advertising and promotion department of The Fair, a large Chicago department store. One of her main projects was the development of The Fair Teen Club. The club attracted teenagers from all over the city, featured amateur acts and fashion shows, brought in guest artists appearing in Chicago theatres and hotels, and once a week put on a radio show over Station WGN. For a long time, young Marilyn Novak had listened to the programs, fascinated, and finally she persuaded her mother to take her to an actual broadcast.

“That was twelve years ago, but I can still see her when she came in,” recalls Miss Kasell. Norma, herself, is beautiful enough to be a movie actress, but she prefers to be a wife and mother, and in her spare time serve as Miss Novak’s appointment straightener-outer and secretary. “She hung back,” Norma continues, “pulling her mother into a back-row seat. It was a relief, really. So many of the teenagers—a lot of them pushed on by their mothers—well, let’s say they were eager to get on the air. And they would crowd me a little. It was refreshing to see one hanging back, so I made it a point to talk to her, and get her to the mike.”

Miss Kasell still marvels at what happened next. “I could hardly believe it. This shy little creature, so big-eyed and beautiful, was all at once the most poised little young adult I have ever seen. I mean it—and I’ve seen lots of them. Everything was ad-lib, but she answered my questions so pertly, and spoke so clearly, and even asked me questions. She was everything an emcee could ask for.”

And what had brought about the trans- formation? How had this shy young girl suddenly emerged as a veteran radio performer?

“I asked her that myself,” replies Miss Kasell. “And do you know what she said? She said, ‘Oh, I can’t act. I don’t know how. I was just pretending I could.’ ”

Kim Novak was born in Chicago on February 13, 1933. For the benefit of astrologers and numerologists, the exact time was 3:33 a.m. and the exact place was Room 313 in the St. Anthony Hospital. Such a generous repetition of threes and thirteens at the beginning of her life has led Miss Novak to regard them as highly auspicious numbers.

From her mother Kim got the blonde hair and fair complexion which is the delight of the photographers who work with her. Another gift was an older sister, Arlene. Had anyone been looking for movie talent in the Novak family during Kim’s undistinguished childhood, he would have unhesitatingly picked Arlene Beautiful and talented, Arlene was the one who excelled in dancing, singing and dramatics; and she, too, was the gregarious one who filled the house with friends.

The first noticeable change came when Kim was ten. It was brought about when Mrs. Novak enrolled her two daughters in Saturday morning classes at the Chicago Art Institute. “We wanted our children to have what we had missed,” explains Mrs. Novak. “So every Saturday I took them down to classes.”

To everyone’s astonishment, it was not gay, outgoing Arlene but shy little Kim who became the star pupil. Kim’s other talent is drawing. With her customary frankness, she has freely admitted that as a high school and college student she was definitely no whiz. But her interest in art. plus the fact that she is a competent artist and sculptor in her own right, is something she has shyly protected from public scrutiny.

In other ways, too, Kim was blossom- ing out. Arlene had met a fellow student named William Malmberg, and from that moment on there had been a rapid thinning in the ranks of admirers who followed her home. In a matter of weeks, Arlene had given Bill exclusive icebox-raiding privileges in the Novak home, but he was not to enjoy the monopoly long. Shy Kim, encouraged by her training as a model, and with her courage further bolstered by her frequent appearances on the air, was soon bringing home icebox-raiders by the dozen.

Spreading her charms safely among the many instead of concentrating on one was a trait that was to continue into Kim’s adult life. While Arlene was withdrawing from circulation with the man of her choice, Kim began playing a field. that was as wide open as the prairies.

Asked if she ever had any special boy- friend, she now gives a stock answer. “I wasn’t interested in any one boy. I just was interested in boys.” This is also borne out by her social career at Wright Junior College, where she was a member of the Alpha Beta Mu sorority. This group had some rather antiquated rules governing freshman girls—no smoking, no cocktails, no lipstick, no dates—that Kim casually broke as a matter of course. She smoked, got sick, and has never smoked since. She mixed her own cocktail, belted it down, and, except for a polite sip of champagne at some Hollywood social function, has never been able to stand the taste of the stuff. But, with her training as a model, she was able to teach her sorority sisters many of the finer points of make-up, to their eternal gratitude, and her breaking of their rules was graciously forgiven. Finally, when the sorority discovered that she could bring in not only a boy for herself, but any number of others to keep filled the dance cards of all the dateless girls in the house. the no-date restriction on her was lifted for the benefit of all.

Kim sometimes wonders about it now. “You know, I envied the happiness of Bill and Arlene in going around steady. Now they have a home of their own and two beautiful children, and maybe I’m the one who should be married and have a house full of kids. But I never was interested in a steady for myself. I don’t know why.”

But, though she had no “steady,” Kim’s life has certainly not been devoid of men. In fact, you might almost say it’s a story of men, and you wouldn’t be far wrong. However, unlike the stories of many successful female stars who use men as stepping stones on their way to the top and then forget them, the men in Kim Novak’s life are still staunchly with her, and she with them, except that now their ranks have increased in number.

Contrary to what is expected of a glamorous star playing opposite glamorous leading men, Kim rarely mixes socially with the heroes of her films. She has her own reasons for her reluctance to become emotionally and socially involved off the set. But when she is asked to state them, her expressive eyes grow large and even incredulous. “Take Frank Sinatra, for instance,” she says. “The only way I could work with him was to know him only as the character he was playing in the picture. That way I could feel sorry for him, and give him the sympathy the part required. But if I joined him at lunch with the rest of the cast, sat around with him like the others do between takes on the set, and really got to know him well, how could I then break my heart over a dope addict fighting to break the habit?”

The same can be said of William Holden, Tyrone Power, Fred MacMurray, and her other leading men. While on location in Hutchinson, Kansas, during the filming of “Picnic,” the cast would meet almost every evening for a cocktail or two, followed by a congenial dinner in the hotel restaurant. Present would be Bill Holden, Rosalind Russell, director Joshua Logan, producer Fred Kohlmar, and possibly six or eight others. But Kim was up in her room on the top floor of the hotel, eating her dinner alone while she studied her script for the next day.

The rest of the cast worried about her solitude, but they needn’t have. “I couldn’t join them,” explains Kim. “I just couldn’t. I knew them as characters in the picture, I didn’t dare get to know them socially.”

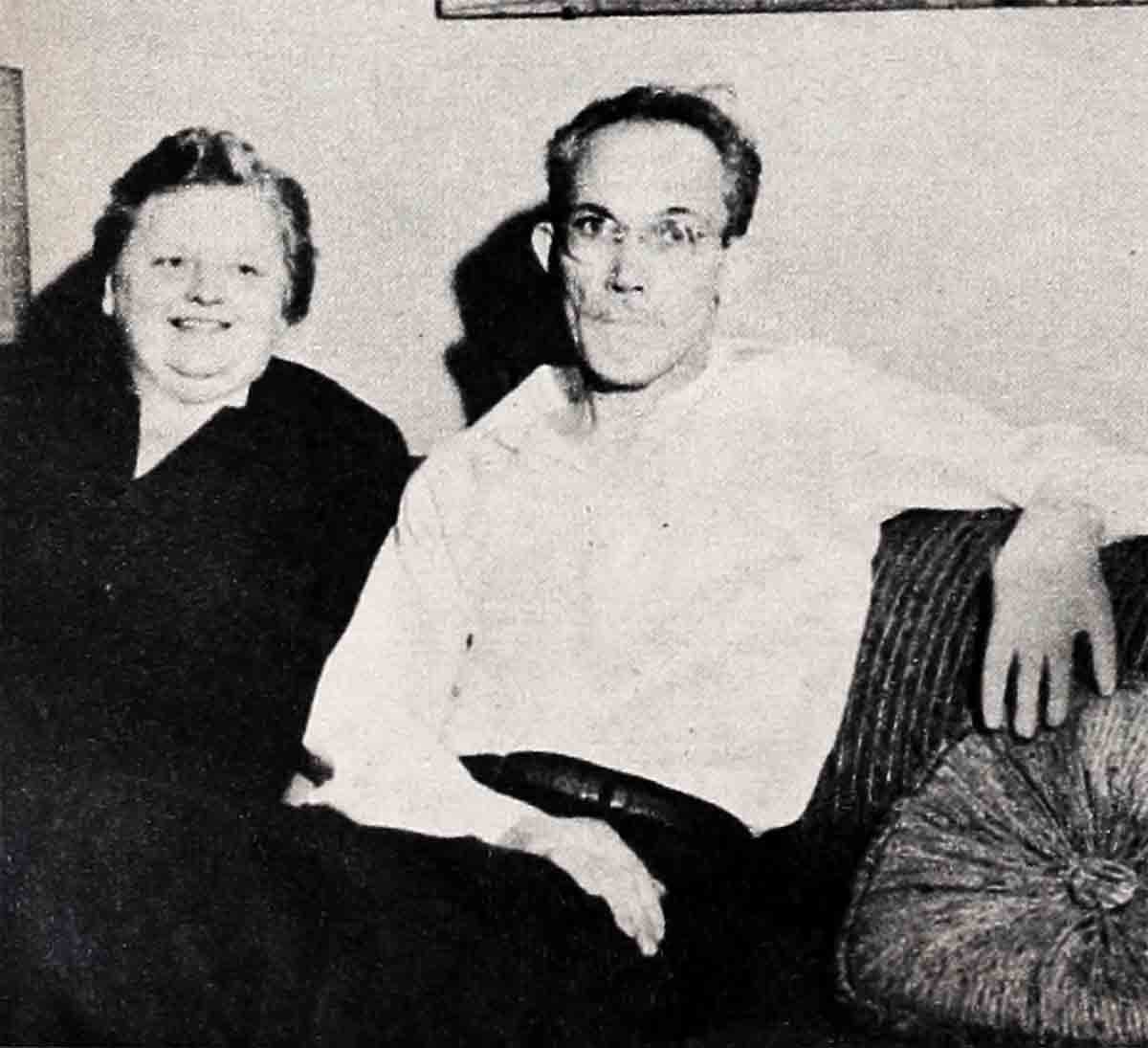

Mac Krim is not only as close to a “steady” as Kim has permitted any man to become, but he is also her Rock of Gibraltar in times of stress. From the time she arrived in Hollywood he has stood by her through all her emotional storms. When things go wrong at the studio, she may briefly burst into tears for momentary relief, but most of her emotion remains pent up until she can release it on his shoulder in the evening.

There has been a tendency to make out of Mac Krim an enigmatic figure that is not in keeping with the facts. Where he confuses everyone is in not conforming to what Hollywood has come to accept as the traditional escort for one of its stars. He is not a playboy. He does not belong to any Hollywood set. He dislikes personal publicity. And while he is handsome enough to be a leading man, he wants no part of the acting business.

Mac explains it all very simply. “I came to Hollywood because I was managing five movie theatres in Detroit. Four of them are neighborhood houses, and one is a first-run theatre downtown, and I came out to see about getting better pictures. I stayed because I like California. Not Hollywood, necessarily, but California, where I can drive a couple of

hours in one direction for mountain ski- ing, or a couple of hours in another for surfboarding.”

As for Kim, he says, “I met her, liked and admired her before she was a Hollywood star. Now that she is a star, I still like and admire her. Stardom can’t change something like that.”

Nevertheless, Kim is still reluctant to turn away from the lure of the open field and the safety to be found in numbers. On her tour of Europe she met Count Mario Bandini, and had a thoroughly enjoyable time furnishing a lot of foundation for the gossip columns. While the Count has made something of a specialty of being seen with beautiful women, and Hollywood stars in particular, he is a long way from being exclusively a playboy. He is a working member of the nobility, his numerous investments interesting him in several lines of business, from canned tomatoes to motion pictures. It is not too surprising, then, that when Kim was in Cannes, in Rome, in Paris, at Lake Como and numerous other places, the Count always found himself plagued with urgent business affairs that required his immediate presence in those very spots.

Unlike most of the dukes and counts who followed Kim around, basking in the reflected publicity, Count Bandini did all that was humanly possible to avoid the press. Not that he could do very much, Kim’s footsteps being dogged by as many as twenty photographers and newshounds during most of her excursions. But she was able to eat a quiet meal with him now and then, for which she was duly grateful. On the ship coming back, her ship-to-shore telephone calls to the Count nearly equalled the cost of her passage, and there were many promises of meetings in the United States in the immediate future. Since then the future has become less immediate.

“Phone calls are so hard to arrange,” says Kim with a resignation that is not excessively mournful. “You have to go through so many exchanges from Hollywood that by the time you get Rome on the phone, all you hear are crackles. Then there is the difference of nine hours in time. If I call the Count when I get home from work at 8 p.m. on Monday, when his phone rings it’s 5 a.m. on Tuesday, and that’s no hour to call a man. And if he calls me Tuesday evening, I’m just going to work Tuesday morning, and that’s no time to call me. Things just don’t seem to be working out.”

A clue to the situation can be found in a gift for Mac Krim that Kim brought back from Lake Como. It was a handsome Italian dressing gown that fitted Mac perfectly.

“How’d you happen to size?” he asked in surprise.

“Oh, I didn’t,” replied Kim innocently. “But Mario was there, and you and he are the same size, so I tried it on him first.”

As the saying goes, when one boyfriend becomes the model on whom gifts for another boyfriend are tried, romance is still a long way from the boiling point.

If Mac Krim has no serious rivals in the romance department, he has several on the professional side, and everything would seem to indicate that for the next three or four years Kim will be more interested in her professional career than in a domestic private life.

For director George Sydney, Kim has already demonstrated her willingness to work until she drops. Currently, she is working so hard on her dancing lessons that, as she says, “My feet have got blisters on their blisters,” but she refuses to stop. Each day she goes to the studio hospital, has fresh bandages applied to her feet and goes right back to work.

“As soon as the music starts, I forget that my feet hurt,” she says sincerely. And with convincing logic she asks, “How can you get your feet toughened up for dancing if you don’t dance?”

Then there is Freddie Karger, musical supervisor of Columbia Pictures and ex-husband of Jane Wyman. He is convinced that Kim’s naturally husky voice with its rich, seductive quality can be brought up to professional standards if her singing continues to improve as it has up to now. “She’s ready right now,” he asserts, “but she needs more lessons to give her confidence. With just a little more work—and Kim is the one who knows how to work—her voice will never have to be dubbed in again.”

And finally there is Benno Schneider, Columbia Pictures’ dramatic coach, possibly the best of his craft in the world. There was the time, for instance, when Kim, surrounded by talented actors and actresses, lost all belief in herself. “Who am I to go on the same set with those people?” she moaned.

“I met a girl like you in Moscow one time,” Mr. Schneider told her, in an easy, roundabout way. “The great Stanislavsky was directing, and all of us had spent years studying under him. He was the man who originated ‘The Method’ which is taught in the Actors’ Studio in New York. We had worked hard, and we knew ‘The Method,’ but this girl, she had never acted before in her life. And he gave her the lead. Well, we resented that, so I went up to him and asked why he gave her the lead instead of one of the girls who had worked hard for it for years. He just said, ‘Wait and see.’

“The girl was a great hit. She got I don’t know how many curtain calls. So again I asked Stanislavsky, ‘How is it she We study you method for years, but she is better without your lessons than we are.’ And he said, ‘You are students, and need all my lessons you can get. But she, well, it could be that she doesn’t need lessons. She is an actress.’

“Miss Novak,” Schneider finished, “it could be you are exactly like that girl.”

Thus reassured, Kim went back to the set and put on a performance that brought about one of those rare accolades in Hollywood, a spontaneous burst of applause from everyone, including the stagehands. Then another difficulty developed Kim looked her best, she walked at he: best, and she thought she was acting ai her best, but nothing was happening. No one seemed able to give a thing.

Benno called her aside after the discouraged director had announced a coffee break. “You are modeling, not acting,” he said.

“But what is the difference?” asked Kim.

“Not very much,” replied Benno. “But a model must be seen, and an actress must see. Beautiful women and beautiful models, they get so accustomed to being looked at, many times they think that is enough, and do not do any looking for themselves. But an actress, she must look, and see what she is looking at, and understand it. Now you go back, and look at the other people, and forget about being looked at yourself.”

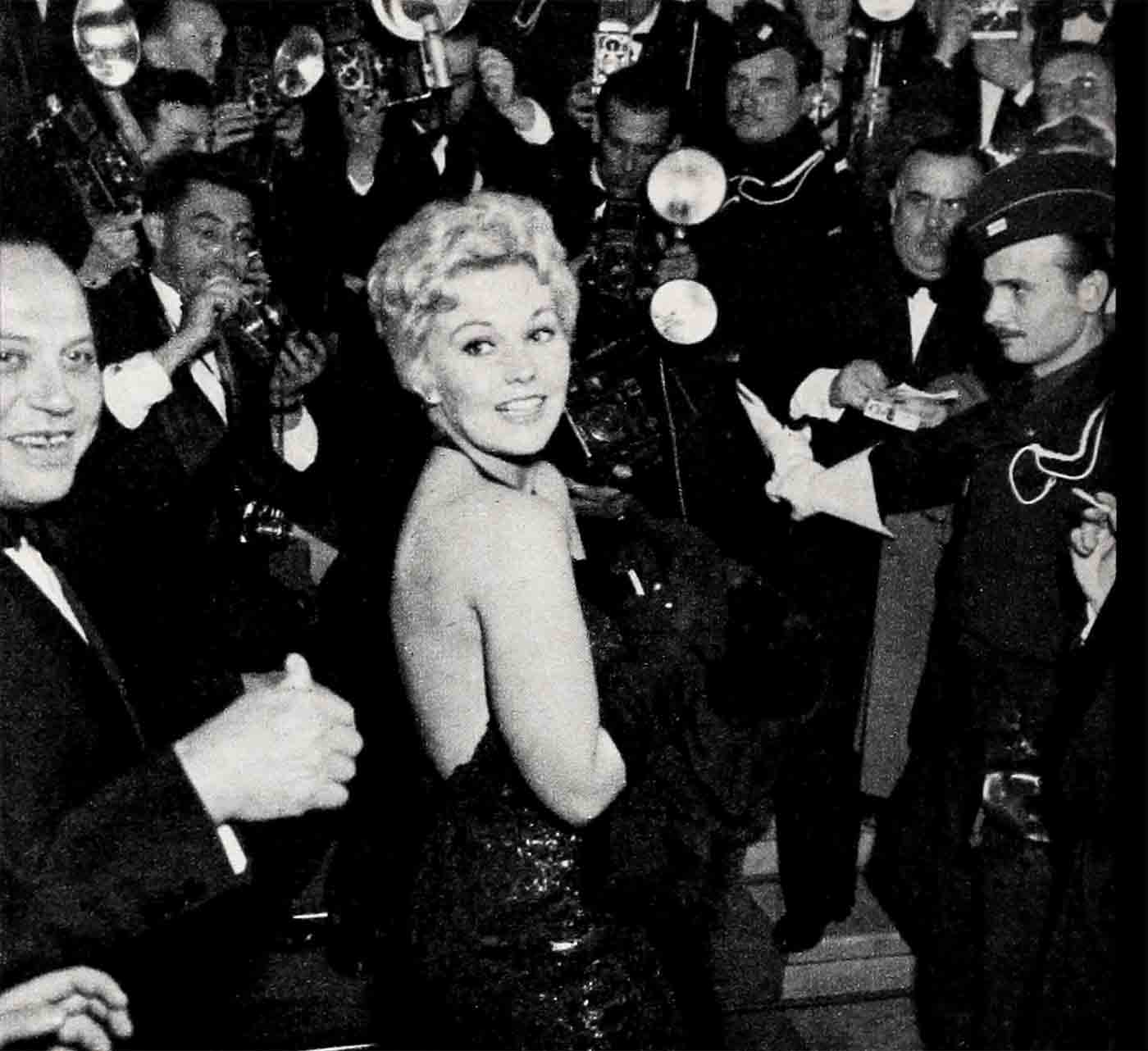

It is a lesson Kim has never forgotten. Many actresses can make a royal entrance in public, be seen by everyone, and sweep regally on without a glance to one side or another. But not Kim. When she makes an entrance, she is seen by everyone, be it at a premiere, in a hotel lobby, or in a restaurant, but with her there is a friendly difference. She is seen, but she is also seeing.

Not that Kim is so lacking in showmanship that she is incapable of staging an entrance when the occasion requires it. Few actresses since the days of Nazimova, Pola Negri and Gloria Swanson have been able to get away with the purple-tinted hair, the purple mascara, and the purple accoutrements Kim uses. That she does get away with them is a tribute to her showmanship, yes, but also a tribute to her naturalness. No one complains. When her mother was informed that Kim had taken to beading her long eyelashes with purple mascara, the response was an amused chuckle. “That Mickey. What will she think of next?” was her unsurprised exclamation.

Qn the other hand, Kim’s very success is raising difficulties of its own. When she first went to New York for location filming of “The Eddy Duchin Story,” George Sydney’s first instructions were that she do nothing but wander around window- shopping for a week. “Look at the people. Get the feel of the whole city. Then you’l! know how Eddy Duchin’s wife felt about her city,” he urged.

For the entire week she roamed New York at will, freely absorbing the atmosphere and gradually becoming a New Yorker, without being stopped for a single autograph. The experience was invaluable, but it is doubtful that its like can ever happen again. With the release of “The Man with the Golden Arm,” “Picnic” and “The Eddy Duchin Story” within a few months of each other, plus the publicity that accompanied her enormous personal triumph at the Cannes Film Festival, Kim became an international celebrity almost overnight. When she returned to New York, requests for interviews, posings for photographers and television and radio appearances came 10 at the rate of 200 a day, and she was al! but mobbed on the streets.

Recalls Mac Krim ruefully, “I met her in New York, and scarcely got to see her. Finally I got her and Mrs. Novak up to Yankee Stadium for a ball game; I thought people there would be more interested in the game than in Kim. Not on your life. By the sixth inning even the umpire would look around to see if Kim approved the way he was calling the pitches, and the crowd around her asking for autographs was backed clear up the aisle. Then a police sergeant got to us, with an escort, and told us if we didn’t leave right away he couldn’t be responsible for Kim’s safety after the game was over. We never did find out how the game ended.”

Jeanne Eagels, whom Kim will portray, was one of the greatest actresses, broken on the rack of her confusion, finally taking to drugs to ease the emotional pain of a world she could conquer artistically but not personally. There is very little possibility of anything like that happening to Kim Novak. Beneath the purple eyelashes and the purple rhinestones sprinkled through her lavender-tinted hair is still the strength and good sense of her peasant heritage. There is, too, a strong sense of self-preservation. This is the thing that has made the men in her life incidental to the work in her life. This is the thing that keeps her clinging to Mac Krim with one hand while she reaches out the other hand to have it kissed by royalty. This keeps her dates with Frank Sinatra infrequent and unimportant. Aside from whether or not she has any romantic thoughts about Sinatra—and she has never permitted herself to be quoted on this—Kim knows that Frank Sinatra is one man to be taken lightly and in very small doses indeed.

A galaxy of men have danced through Kim’s lavender life and danced out again. She has lunched with Aly Khan and, according to published reports, bitten his ear lightly while dancing with him. She was reported “engaged” to Count Bandini and denied it by saying, “How can I be engaged to two men at once?” She has appeared at premieres with Frank Sinatra, and young Nick Adams is her willing slave. But something strong—tenaciously strong—keeps Kim toiling steadily onward and upward toward a goal which, in the beginning, she didn’t want at all.

After “The Jeanne Eagels Story,” Kim will make “Pal Joey.” Once more she will be teamed with Frank Sinatra. Once more, undoubtedly, romance rumors will link their names. Count Bandini may still hover in the background. Mac Krim will still hover at her side. Directors and others with whom she works will be in the foreground and the background— coaching, advising, scolding, pushing—making of her what the executives of Columbia Studios say, without equivocation of any kind. will be “the greatest star in America today.”

And when it’s over, when the shouting has died away and the crowds melt and the lights in the theatre go off; when Kim Novak stands before her mirror in her lavender apartment and slowly wipes away the purple mascara and takes off the purple eyelashes, only she will know whether the decision she has made was the right one. The decision was not whether or not to be a star. The decision was an even more difficult one—to be what people thought her, to live up to what people expected of her.

That, she has done, and as we say goodbye to the girl with the lavender life we can only make one prediction—that she’s here to stay.

THE END

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE DECEMBER 1956

No Comments