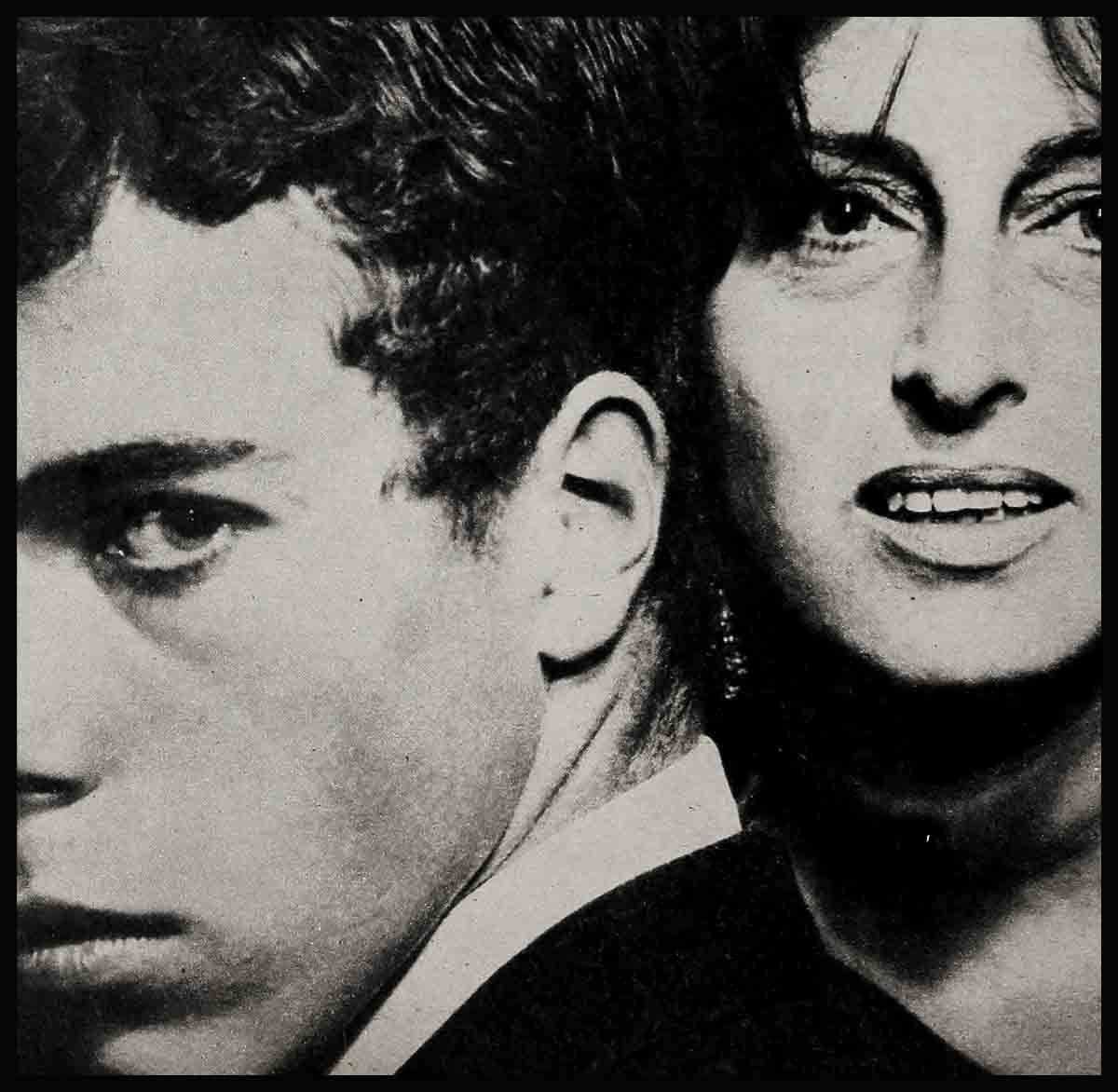

The Lame Boy Who Walked With God—Anna Magnani and her son Luca Magnani

Anna Magnani awoke. Even though she had slept badly the night before, moving nervously about the big dark-canopied bed and dreaming long nervous dreams, she smiled. For it was morning now, the morning of il giorno felice, the happy day. And so what that the sun was not shining outside and that it rained gray and hard, instead? If Rome had been hit by a rare snowstorm this day, or even a hurricane or a typhoon, it wouldn’t have made any difference. For this was the happy day for Anna. It was her son Luca’s day. It was his sixteenth birthday and that night there would be the party for him, his first party. And for the first time, really, after so many strange and lonely years away at that far-off hospital, he would be able to enjoy himself.

And so, though the palms of her hands were wet and though she noticed that her breathing was heavy, very heavy, she smiled. And she got up from bed. And the happy day began.

In the kitchen, a few minutes later, she sang as she started to prepare a breakfast. And when her maid of many years, a little buxom old lady with straight gray hair and small gray eyes, walked into the room and stared at her in amazement, Anna burst into a deep long laugh.

“You are surprised, hah?” she said. “Only eight o’clock and Magnani is up. Only eight o’clock and Magnani sings. And look at Magnani—in the kitchen for the first time in how long, and near the stove, and making the cocoa and the toast. . . . And you are standing there and thinking that Magnani must be walking in her sleep, no?”

“No,” the old lady said, uncertainly.

Anna laughed again. Then she rushed over and hugged the servant.

“In case you have forgotten,” she said, “today is Luca’s birthday.”

“Ah,” the old day said, remembering now, understanding.

“And,” Anna went on, “today is the day I am going to tell the director of my picture, ‘I don’t work today, I don’t care what you say. I work too hard all the time and I rush to the studio too early all the time. But today is my son Luca’s first birthday with me in so many years and I stay home today and in the morning I make him his breakfast, in the afternoon I make him his lunch and, at night, I make him his party.’ ”

“You said good,” the maid told her, approvingly.

“Yes,” Anna chuckled. “And—” she started to say.

But the old servant interrupted her with a poke.

“Signora,” she said, pointing to the stove, smiling now, too, “your cocoa. . . . it is burning.”

Anna turned and rushed over to the steaming pot. “O Dio,” she cried out. She looked into the pot, at the brown violently-churning bubbles. “Oh, what do I do? What do I do?”

The old servant turned off the gas.

“Just this,” she said.

Anna nodded. “Today I am very excited,” she said. “It is a day on which nothing must go wrong and I get confused and I am excited.”

“Nothing will go wrong,” the old servant said. “Do not worry, Signora.”

Nothing must go wrong

Anna sighed. The smile was gone from her face momentarily, the laughter was gone from her voice. “Nothing must go wrong,” she said. “Not today. No. Not today. . . .”

She tiptoed into Luca’s room a little while later, carrying his breakfast in a large silver tray. She laid down the tray on a small table next to his bed and, for a moment, she stared at her sleeping son.

“How handsome you are, my young man,” she said to herself, the pride rushing through her body, “how handsome, my young man, my son, my baby.”

She bent and kissed him on the cheek.

“Luca,” she whispered, gently.

He did not wake.

She ran her fingers through his dark, wavy hair.

“Luca—”

As she continued looking down at him she remembered how he’d been that other morning, a long time ago, thirteen years ago.

Luca, three years old then, had awakened with a fever. She, Anna, had been worried and had wanted to stay home from work that day in order to be with her little son.

But when she’d called the studio—where she’d begun work a few weeks earlier on her first major picture, Open City, the picture that would make her an international star—and told her producer that she couldn’t make it that day, he had begged her to reconsider.

“Today is an important scene,” he’d said. “Everything is in readiness for it. Come today, Anna, and tomorrow you can stay home, I promise.”

So Anna had gone to the studio. And she’d been at work only two hours when she got the phone call.

It was a doctor. He was calling from her apartment. He explained that shortly after she left her son had begun to appear very ill and that her maid had taken the liberty of calling him.

“Now,” he said, “I think it would be good if you left what you are doing and came here right away.”

“What’s wrong?” Anna asked, more frightened than she had ever been in her life. “What has happened to my baby?”

“Come . . . and we will talk,” the doctor said.

The day the polio struck

When Anna rushed into the apartment a little while later, the doctor took her hand and led her to a couch.

“The boy’s father—you and he are divorced?” the doctor asked.

“Yes,” Anna said.

“I thought perhaps I should like to talk to him, too,” the doctor said.

“He is not in Rome right now,” Anna said.

She jumped up from the couch.

“But about Luca, Doctor,” she asked, “what do you want to tell me about my son?”

“He is sick,” the doctor said.

“How sick?” Anna asked. “How sick?”

“He is sick with polio,” the doctor said.

Anna screamed.

“Nooooooo!—” came the sound from deep inside her, filling the room with its despair.

“No . . . no . . . no . . . noooooooo!” came the sound, over and over again.

And then she’d run from the room to the bedroom where her sick son lay.

She’d opened the door.

She’d walked in.

She’d looked at him, in his bed, asleep . . . and then she’d run her fingers through his long brown hair, warm with the terrible fever that burned within him.

And then, as now, on this day, thirteen years later, she’d whispered his name.

“Luca . . . Luca.”

Slowly now, he opened his eyes.

“Wey!” Anna said, sitting on the bed next to him, pulling at his hair now, her voice loud again, “look how we start your sixteenth birthday. With breakfast in bed, my Luca, like an emperor on vacation.”

Luca smiled groggily.

Anna handed him a cup from the tray. “Here,” she said, “cocoa, the way you like it, with the rich milk of the goat.”

She watched him take a sip.

“Good?” she asked.

The boy nodded. “Very good,” he said.

She pulled at his hair again.

Then she asked, “Luca, do you know what arrived from the tailor last night, late, after you went to bed? Your tuxedo. The suit you will wear tonight to the party.”

She clapped her hands together, strong and loud.

“And what a party it will be,” she said. “Your mother has gone wild with herself. She has rented the best nightclub in the city. She has invited one hundred people. There will be food, Luca, and wine, the very finest wine. And there will be music and entertainment and it is for you, my boy, to celebrate for you.”

Luca nodded again.

And as he did Anna laughed again and continued talking—about the night ahead, the party, the plans. And then, when she was finished with her talking and Luca had finished his cocoa, she jumped up from the side of the bed.

Magnani honors her son

“Now I must go for a little while,” she said. She made a face. “To the istituto di bellezza I go, the beauty salon. Aaaaaach. How I hate those places. But today I go. You know why, my boy? Because tonight I must look beautiful. Tonight nobody says, ‘Look at Magnani, the sloppy one.’ Tonight they all say, ‘Look at Magnani, the beauty. And,’ they will say, ‘do you know the reason she is so beautiful tonight? Because she is honoring her son on his birthday. And because for this night, this one night in his life, she must be the most beautiful woman he has ever seen.’ ”

She took his hand in hers.

“You look forward to tonight, Luca?” she asked.

“Yes, Mamma,” the boy said.

For a moment, neither of them said anything.

Then Anna asked, “Do you want anything else before I go?”

“No, Mamma,” the boy said. “I will get up now and wash and dress.”

He began to sit himself up in the bed.

Anna watched the great effort it took him.

“All right, my boy,” she said.

And she left. . . .

“Subito,” Anna said to the beautician—a tall, pretty, olive-skinned girl—as soon as she’d entered the beauty salon. “I don’t have much time. So quick. Make me look nice. And let me get out of here!”

The girl was impressed. This was a very elegant place she worked in, yes. But customers like the great Anna Magnani didn’t walk in every day.

“Of course,” she said, “I will get you out of here subito-subito.”

She began her work quickly, quietly.

But after a while, like all members of her profession—male or female, old pro or novice, she began to talk.

And Anna, normally opposed to any unnecessary conversation, didn’t seem to mind on this day.

“You are, if I may ask, going to a party of some sort this evening?” the girl asked.

“I am giving a party,” Anna said.

“Ah, you have won another Oscar in the United States, I bet,” the girl said.

“No,” Anna said, laughing. “This is different. This is more important. I am having a party to celebrate the birthday of my son.”

“You have a son, Signora?” the girl asked. “I did not know that.”

“I do, but yes,” Anna said.

“How old is he?” the girl asked, as she continued her work.

Anna told her.

“The beginning of young manhood,” said the girl.

Anna nodded. “And the beginning of a new life with me,” she said. “He has been away a long time, in Switzerland. But last week he came back to me and that, too, I am celebrating . . . Would you like to see a photo of him?” she went on, proudly. “We were at my country house in Circeo till yesterday and I took some very good photos of him.”

“Oh yes,” the girl said, “I would like very much to see him.”

Anna realizes the truth

As Anna reached forward for her purse, the girl asked, “Has he been in school in Switzerland, Signora?”

But Anna didn’t seem to hear her.

“Here he is,” she said, finding the picture she was looking for and handed it to the girl.

The girl wiped her hands on a towel. And then, carefully, she took the picture and held it in her fingers.

“Mmmmmmmm—” she said, looking at it and breaking into a great smile. “But he is handsome, Signora. But he is so handsome.”

“Grazie,” Anna said, “thank you.”

“Oh Signora,” the girl went on, “I mean no disrespect, but if I were at this party tonight and I saw your son, do you know what I would do? I would forget all the etiquette that my mother and father have taught me and I would walk up to this son of yours and I would say, ‘Would you please, my handsome young man, do me the honor of having the next dance with me?’ ”

She laughed a high, girlish laugh.

“And what do you think he would answer me, Signora?” she asked then. “You should know. You are the mother.”

What humor and happiness there had been in Anna’s expression was gone now, suddenly.

But the girl, standing behind her, didn’t see Anna’s face as she repeated her question.

“What do you think he would answer me, Signora?”

Finally, after a long pause, Anna replied.

“He would say, ‘No, I am sorry, but I cannot have this dance with you,” she told the girl.

“He is conceited perhaps?” the girl said, gayly.

“No,” Anna said, shaking her head. “He is not conceited. He is crippled in both his legs.”

“Oh, Signora—” the girl started to say in apology.

But again Anna did not hear her.

Because she was afraid now, very much afraid now, of what she had almost done.

It was a little while later. Anna and Luca were in the living room of the big hilltop apartment. Luca sat reading what appeared to be a magazine. Anna stood near the window, staring down at the city below and at the dome of St. Peter’s, a few kilometers away, which dominated the entire scene with its somber, oval beauty. She’ was thinking—very hard.

Suddenly, she turned.

“Luca,” she said, “in a little while I will fix us our lunch.”

“Good Mamma,” the boy said, looking up from what he was reading.

“But before that,’ Anna said, “I would like to talk to you about something.”

She walked over to where he sat.

“The party tonight—” she started to say.

But then she changed her mind. She would tell him about that in a little while, about how she had decided to call off the party, about how she realized now it was a stupid and ridiculous idea to drag him to this party she’d planned, this party where he would be so unhappy and uncomfortable, where—Oh God, why didn’t she realize it sooner—others would be dancing and tapping their feet to the music while he, Luca, would sit there, tortured, ashamed, miserable.

Another idea

For now instead, she thought, she would tell him about her other idea.

“Luca,” she said, “I have a plan—for you, and for me.”

She chose her words carefully as she continued to talk.

“Do you know how hard I have been working these last years—here in Italy, in France, in America?” she asked.

The boy nodded. “I know,” he said.

“Well,” Anna said, “I think that in a few years I will stop working . . . and retire. Yes, I am getting tired. And I need rest. And now you are back from Switzerland and I need to be together with you more . . . And do you know what I am going to do? This I am going to do. I am going to make a few more pictures—maybe two, maybe three. And then I am going to take all the money I make from those pictures and buy a villa, far away, very far, away from everyone and everything. And you and I will go there, Luca, just the two of us, alone, and we will spend our time there, just the two of us, together . . . forever.”

“Why, Mamma?” the boy asked.

“So no one will ever be able to hurt you,” Anna wanted to say.

But instead she said, “We have thirteen years apart to make up for, Luca. This is a long time for a mother to be without her son and for a son to be away from the mother who loves him so much. This way, in this villa, we will be away from everything but ourselves. And we shall make up for those thirteen years, you and I. Oh, how we shall make up for them!”

She smiled and reached for her son’s cheek and gave it a playful squeeze.

And she waited for him to smile back.

But he didn’t.

“You do not like my plan?” Anna asked.

“If it is your wish,” the boy said.

“It is,” Anna said.

“Then I guess it is good,” the boy said.

Anna took his hand.

Again, she waited for him to smile.

But again the smile did not come.

“Luca,” she said, “—you are sure there is nothing wrong . . . ?”

The boy shrugged.

“Only,” he said, “that I will not be able to go to the school I have been reading about.”

He looked down at the book in his lap.

Anna followed his gaze.

For the first time, really, she saw the book. It was not a Magazine, as she had thought, but a college prospectus.

The Rome Institute of Engineering, read its title,—A Description of Courses for he Interested Student.

“Oh?” Anna said, looking back at him, surprised.

I realize it would not be easy to get into the school,” Luca went on. “And I realize that if I do get in it will not be easy at first, being in a crowded classroom with so many students, after all my years in Switzerland, at the hospital, where our classes were always private and where we always studied alone.

“But,” he said, “though I have never told you this before, I had looked forward to trying to become an engineer, Mamma. And to getting used to being with people, and not being away from them anymore, all the time.”

“With people?” Anna asked, repeating him. “With people?”

“Yes,” the boy said. He smiled. “That is why, too, I am so happy to be in Rome now. And why tonight; this party you are having for me—why I look forward to that so much. I must learn, Mamma, not only from the books I will study, but from the people I will be with now.”

“But the party,” Anna said, “—this morning when I reminded you of is thought you looked a little sad, Luca, as if perhaps you were not looking forward to it.”

“I was not sad, Mamma,” the boy said. “I was thinking about the college. I had written to them from Circeo asking for this booklet and it had not arrived and I guess I was wondering if perhaps they did not want me and were not even sending the booklet . . . But it arrived, Mamma, just a little while after you left the apartment this morning.”

“And you are happy now?” Anna asked.

“Yes,” the boy said.

“And about the party—you are happy about that, too?” she asked.

“Yes,” the boy said.

But he did not look so happy.

“Only you are not happy about one thing I said,” Anna went on, “about the villa I spoke of, the faraway villa. Is that not right, Luca?”

“If it is what you want, Mamma—” the boy started to say.

“No,” Anna interrupted him. “I do not want that. I thought so for a minute. But no. That is not what I want.”

She reached over and took him in her arms and hugged him.

“I want only that you are happy,” she said.

The boy who walked with God

“I am happy now, Mamma,” Luca said. “And the only way I can be any happier is to work to make you proud of me someday . . . And I will, Mamma. God will help me, I know. You just wait and see how proud you will be. You just wait until the day you hear somebody say, ‘That Luca, the Magnani’s son, it is a shame that he does not walk—but what an engineer he is, what a fine engineer!’ ”

And it was as he was saying this that Anna heard the bells in the distance—the bells of St. Peter’s—softly at first, and then louder and richer and more and more beautiful in their melodious confusion.

She smiled.

Oh, she was so proud of her boy, her good, brave boy.

It was noon, she knew—noon, the heart of the day, the moment of hope, the moment when the long, cool, wet morning is over and when the sun shines strongest and brings promises of warmth and good to the soul of man.

She looked over toward the window.

Yes, she saw, the gray, rain-filled morning had vanished and the early afternoon sun was shining now.

She looked up.

Her smile became radiant.

Her son had faith, and she would have faith.

Thank You, she whispered to herself, for giving me back my son . . . so strong in his heart, where so many others are lame and weak. . . .

THE END

—BY ED DEBLASIO

It is a quote. MODERN SCREEN MAGAZINE MARCH 1959