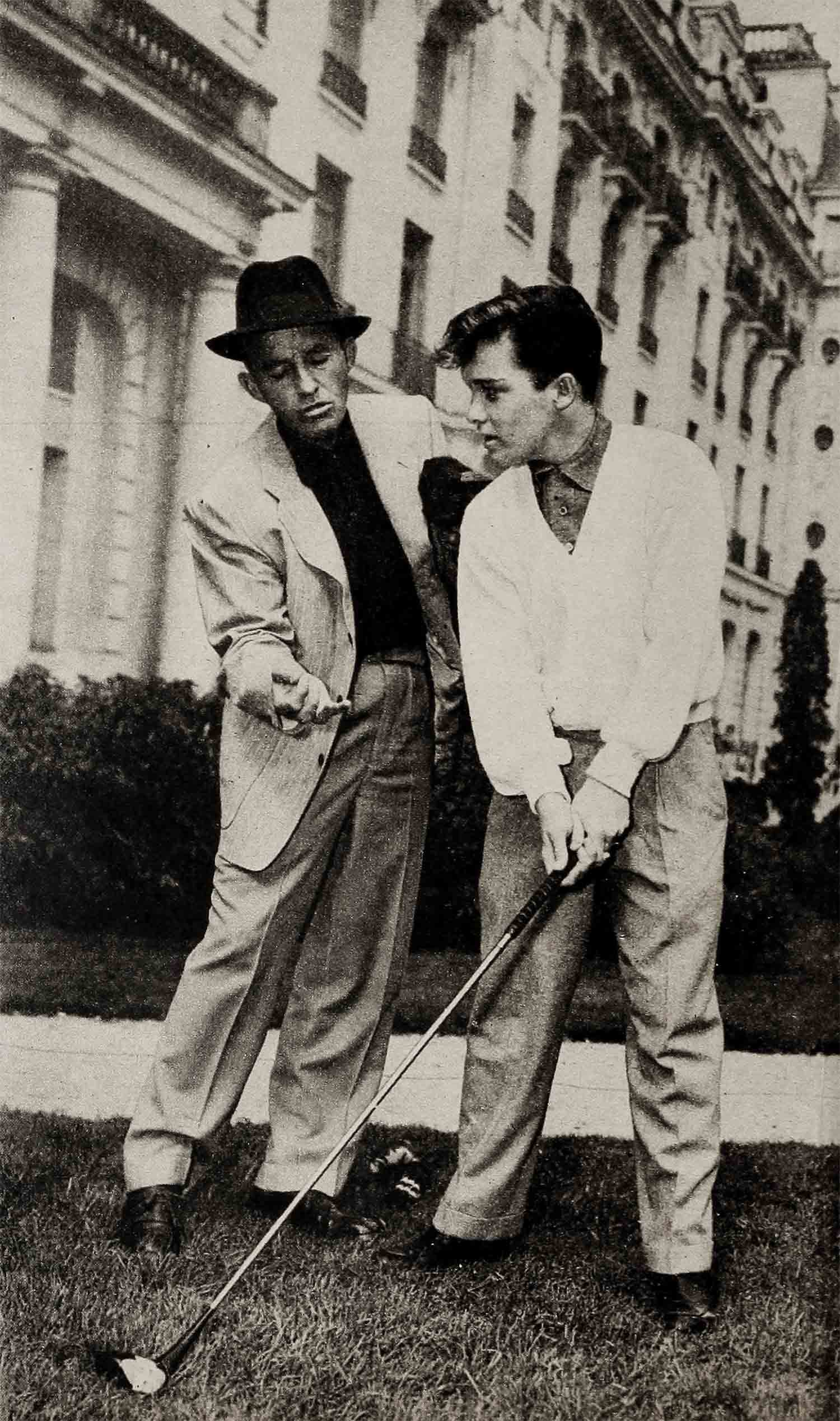

Bing Crosby And Son

Bing Crosby and his traveling sidekick, a sharp, polite, well-bred boy of 15 who happens to be his youngest son Lindsay, will return from Europe to Hollywood on June 25th.

This knocks into a cocked hat once and for all the rumor that Bing was planning to remain abroad in order to rendezvous in peace with beautiful Mona Freeman, his sometimes dining companion.

When Bing arrived at Cherbourg aboard the Queen Elizabeth last March, reporters descended upon him and asked first, “Is it true, Monsieur Bing, you are engaged to Mademoiselle Freeman?” and second, “Is it not true that you plan to marry Mademoiselle Mona Freeman?”

Lindsay, who loves to see his old man wriggle out of a tight spot, wisecracked with Sue Robertson, Bing’s secretary, as the old groaner, momentarily perturbed, collected his wits for a denial.

“Now, look,” Bing said, “I’ve known Mona ever since she was a kid. There’s absolutely nothing to that story. Once in a while down at Palm Springs we took dinner. That’s all.”

And when Bing said, “That’s all,” he meant it, because in the three months of his European sojourn, Mona Freeman was the one subject he would not discuss.

“We just came over to play a little golf,” Bing explained. “I also thought it wouldn’t do Lindsay any harm to get around a little you know, see Europe, study a little art. He may have some talent along pee lines. He paints fairly well for a kid.”

Actually, Bing came over to Europe for two reasons: (a) he likes privacy, to do whatever he feels like doing without attracting public attention and (b) because he knew that a trip would serve as the antidote to Lindsay’s sadness brought about by the death of Dixie Crosby.

As a matter of fact, Bing over the years has made it a practice to spend as much time away from Hollywood as in it. Once he finishes a film and tapes a few radio shows, he takes off for the house in Carmel, the one up at Hayden Lake, or the ranch in Elko. Within the next few weeks he and the boys will undoubtedly go up to Nevada and work on the ranch during the summer.

In Hollywood, Bing has the feeling that he is being tracked by bloodhounds. As a writer friend of his once put it, “Let Bing ask for change of a dime, and right away some reporter is making a big thing of it. That’s why, after Dixie died, he took Lindsay out of school and went down to Palm Springs. But even there he couldn’t get away. The papers played up this thing with Mona Freeman as if it were a full-fledged romance. It wasn’t.”

Bing Crosby is an Irishman who lives in a kind of cathedral-like self-sufficiency. He has few close friends, his closest being Bill Morrow, his writer.

Crosby confides in no one, especially about affairs of the heart. He is not a man who wears sadness on his sleeve. In fact, for a man who makes his living as an actor he is the most atypical actor in the business. The Crosby legend in which Bing has been painted as the gay, carefree, light-hearted, insouciant crooner with no depth of intellect or emotion is at complete variance with the facts.

Bing is a little on the sullen side. He refers solitude which is why he loves to fish and hunt. He is a man who meditates, who has his own philosophy of life, a man with moods and tempers and discernment.

Take, for example, the way he lived in Europe. Most American stars who come to Paris check in at one of two hotels. The Lancaster or the Georges V. These are plush, expensive hostelries, primarily for foreigners, and if you ever catch a Frenchman living in one of them, the chances are that you’ll be rewarded with the Legion of Honor, They have become known in show-business as Hollywood hotels. Rita Hayworth, Susan Hayward, Olivia de Havilland, Clark Gable—when any of these touch Paris, right away it’s the Hotel Lancaster or the Georges V.

Crosby, on the other hand, stays at the Trianon Palace, a quiet, expansive, picturesque hotel out in Versailles, ten miles or so from Paris. “It’s a good spot,” his son Lindsay agrees. “Dad and I can get up in the morning, shoot a round of golf. Nobody bothers you. The service is swell, and of course, it’s very historic. Marie Antoinette and all that. Good for my history.”

Bing prefers to make Versailles his European headquarters because the newspapermen in and around there rarely bother him. They interview him when he arrives and when he leaves and what he does with his time in between is his own business. There is no daily accounting of his schedule. Der Bingle loves anonymity.

During the middle of April, for example, he, Lindsay and Bill Morrow jumped into their car and pulled out of Paris, heading for the Spanish border. Their itinerary was their own affair. No one cared. No one ogled them. No one asked for snapshots, autographs or interviews in any town enroute.

When the trio arrived at Biarritz, they stayed for a day at the home of the celebrated French comedienne, Gabrielle Dorziat with whom Bing appeared in Little Boy Lost. Bing was asked to show up at the Cannes Film Festival and said casually enough that he might drop in for a few hours, but he was anxious to get to Spain and introduce Lindsay to the bullfighting scene.

After Spain there was the Italian tour and then the return to Paris. By this time, Bing, who is much less a disciplinarian than Dixie was, became convinced that Lindsay had had enough fun and enough golf. It was time for the lad to settle down to some serious study. Bing engaged a well-known painter named Mayo, to work with Lindsay on his painting for at least three hours a day.

It’s too early to tell at this point, but it looks very much as if Lindsay has a great deal of potential as an artist. “I like to paint,” he says, “and I learned a lot in Paris, but I don’t really know yet what I want to be.”

Lindsay’s twin brothers want to become ranchers and his older brother Gary talks of becoming a football coach.

When Bing took Lindsay out of private school in Beverly Hills last year, the opinion was offered that the boy’s education might suffer. Actually, Lindsay believes, “I’ve learned more these past few months than I have in years of schooling.”

Bing believes in formal education very strongly—he sent his boys to a Jesuit preparatory college and he himself went through Gonzaga, but when Dixie died, he realized wisely enough that for a few critical months, months of transition, he would have to be both mother and father to Lindsay. He would have to give him both affection and companionship.

Bing has done the job extremely well. Lindsay has not only adapted himself to life without a mother but new horizons, new vistas have been opened up for him. Bing has seen to it, subtly and seemingly without effort but always according to plan.

Lindsay Crosby is bright and alert without being pushing or forward. In France he and Bing began to speak French to each other, and they had some pretty riotous linguistic sessions.

In view of the fact that Bing took Lindsay to Europe this year, he can’t very well put himself in the position of playing favorites which means that come next year, he will undoubtedly have to do the same for Phil, Dennis, and Gary.

Just what effect Bing and his four sons would have on continental Europe is very difficult to tell. Sometimes, Europeans resent Americans for no good reason at all.

Take the incident of Bing and the British Amateur Golf Championship. While Bing was in Paris he said he planned to enter the British golf tournament at Hoylake whereupon columnist Desmond Hackett of the London Daily Express sat down and nastily wrote that Bing should be barred from the tournament. Hackett blasted Bing and insisted that the crooner had turned the 1950 Amateur tournament at St. Andrews, Scotland’s oldest golf course, into a cheap circus. He also accused Bob Hope of making an “ass of himself” and “even a bigger ass of British golf.”

The attack on Crosby who was playing for charity seemed so unfair that the influential London magazine, “Golf Illustrated” came to Der Bingle’s defense. “It has been suggested,” the magazine said, “that Bing is not a good enough golfer to play in the event. We do not agree with that at all. He is certainly better than many of the home players who enter.”

The magazine then went on to defend Crosby both as a golfer and a gentleman. It declined, however, to do the same for Bob Hope. Said the magazine, “We rather think that in this instance Bing has been again confused with his friendly rival Bob Hope, whose display of bad manners and bad golf is still unfortunately in our memories.”

Outside of England, however, neither Bing nor any member of his family has ever been adversely criticized. Bing is universally liked although he has never pandered to popularity. “I’m a lazy man by nature,” he says, “and I do what comes naturally.”

It is the course of Bing’s nature to do the right thing. Paul Whiteman who gave the crooner one of his first jobs, has said of Bing, “He goes through life trying to help people, and where he can’t help, he always makes sure not to harm. He is a credit to America, a credit to show business, and a credit to the revered memory of his wife.” Thousands echo this homage.

If any of Bing’s four sons grow up to be half the man their father is, the world will hold them in high esteem.

THE END

—BY STEVE CRONIN

It is a quote. MODERN SCREEN MAGAZINE JULY 1953