Diary Of A Lonesome Wife—Jean Simmons

“I’ll be back before you know it,” Stewart Granger told his wife, trying to make light of the five months he expected to spend half a world away.

Jean Simmons agreed brightly. But in the back of her mind ran a phrase, a typically American phrase, which seemed to be a more appropriate answer. “I hear you talking,” it went, “but are you making sense?”

Well, maybe he was. If you are an actor, you play your cards where the game is best. After all, their profession brought them a good living, a darn high level of living, to tell the truth, and it didn’t make sense to cry about the unavoidable drawbacks. As the old cliché says: “Play the game, darling.”

Jean knew she must. And she does. But it isn’t too easy.

After Jimmy Chis real name is James Stewart had left for Pakistan last February to make Bhowani Junctionwith Ava Gardner, Jean began to go for long walks along the fire trails over the hills around their Beverly Hills home. She took along not only her two beloved miniature poodles, “Young Bess” and “Old Beau,” but a third companion who was Jimmy’s latest present to her, a bright-eyed, long-nosed, black and white quadruped classified by Jimmy, as a “true-blooded” Tibetan water spaniel. “His name,” he told her gravely, “is Meetoo-Shih-Tzu, and among the Buddhists of Tibet, dogs of his breed are counted as temple dogs.”

You could never tell about Jimmy, but you could soon tell about “Meetoo”. He was a real companion. The poodles hated him at first, but he quickly won them over with a wild, ear-flipping kind of gaiety. And he was crazy about the walks over the hills, reminded by them of his native Tibetan mountains, she figured. So when there was nothing else to do Jean would walk herself and her dogs silly. And for the first few nights after Jimmy was gone she enjoyed a certain “liberty” around the house—or thought she did.

“At least, now I can see what I want to see on the television, without interference!” she told Bill Rushton, Jimmy’s former orderly of his British Army days, who manages the household for them.

She meant that up to now she had always been obliged to give up looking at the dramatic and comedy shows she liked because Jimmy (and Rushton, too!) always tuned in the fights or other sporting events. But it didn’t turn out as she had planned. Watching TV just wasn’t the same, somehow, when Jimmy wasn’t there. She would be watching some play which seemed never to get anywhere, Rushton would be out in the kitchen splashing the dishes about, and things were dull, dull, dull!

And that was when she began to feel grateful for being tired evenings. And for more than a week after her picture started, she would come home, eat sparingly (for good reason—she had really made a “porker” of herself during her winter trip home to England), and be happy to tumble into bed.

There was solid reason for her weariness, of course. In Guys And Dolls she not only had an exacting characterization to fill, but there was some singing and dancing to do—something quite new for her. Once before, in an English picture called Way To The Stars, she had been asked to sing. The director, Anthony Asquith, had listened to her with deep concentration, after which he had advised: “You had better stick to plain acting, my dear.”

Nevertheless, Joe Mankiewicz, who was directing Guys And Dolls for Samuel Goldwyn, and who had written the screenplay adaptation from its Broadway presentation, insisted that Jean use her own voice. He pointed out that in the picture she played the role of a Salvation Army lass, not a professional singer, and what she had to be was herself, not Lily Pons.

The singing and dancing, and working in strenuous scenes with such stars as Marlon Brando, Frank Sinatra and Vivian Blaine called for a big outlay of mental, as well as physical, energy.

She was going to write Jimmy about her singing; she was going to say something funny, like, “. . . and I did it all without once using a throat atomizer,” but she didn’t. In the first place, no letter from Jimmy came for her until almost a month after he had left—so wretched was the mail service from Pakistan. And, to tell the truth, no letter from her to Jimmy had even started—so horrible a correspondent was she, she realized with a guilty twinge.

But she came to think about that later. First there were the walks with the dogs. Then there were the rides she would take in her Jaguar. On one of these she came to realize that the unusual has an odd habit of occurring in a girl’s life when events find her without the protection of the man she has depended on for so long.

She had stopped her car at a street corner for a red light when a strange man walked over and started ing to her.

“Back where I come from we admire beautiful women and fast horses,” he said. “In Hollywood I guess it’s a case of pretty women and these here scat cars. Ain’t that so, Ma’am?”

Jean didn’t know. When she saw the light change she “scat.”

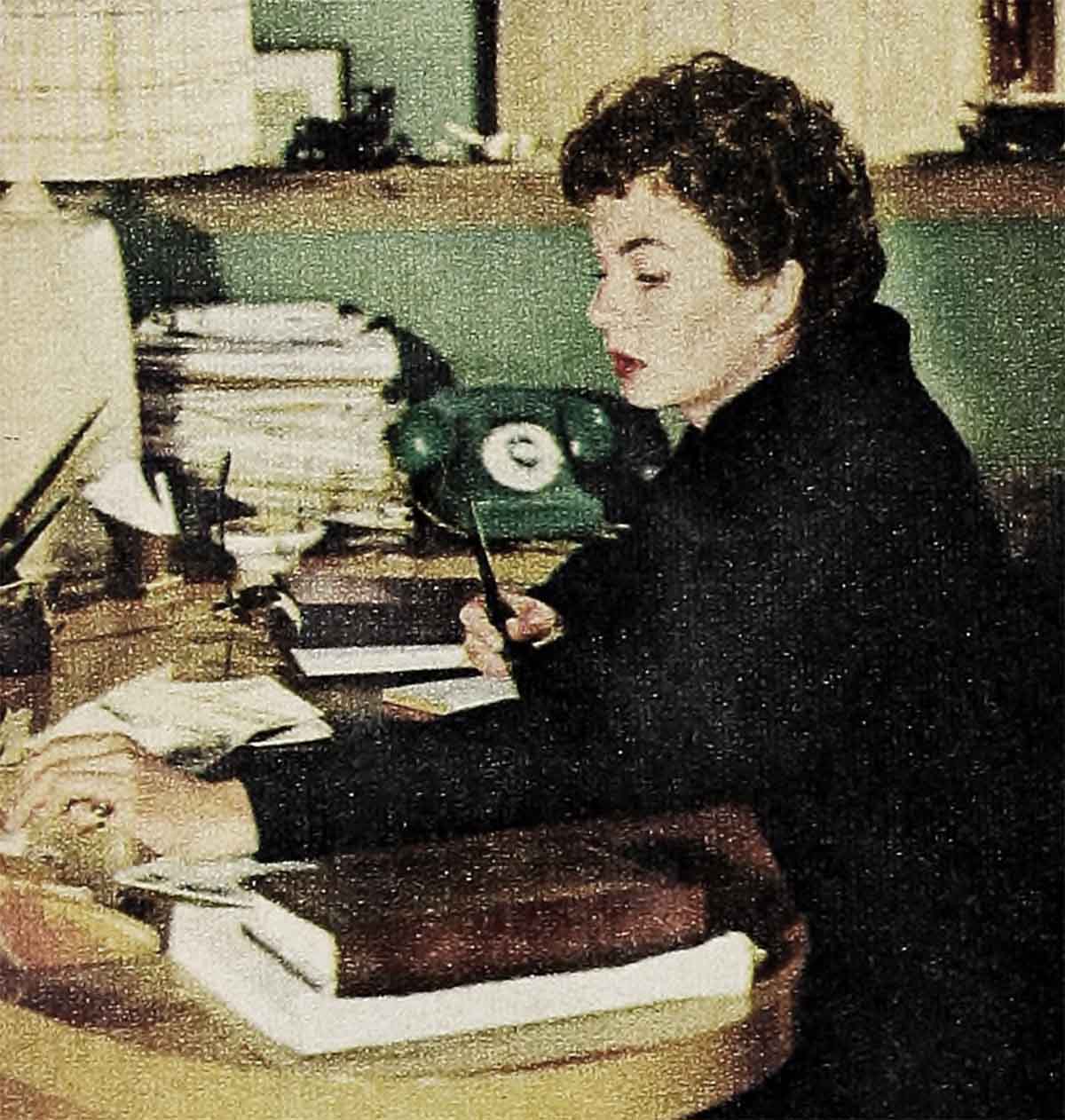

And during the first week or two after Jimmy left the only feeling she had besides the fatigue caused by her work was a certain apprehension which gripped her whenever she happened to pass the telephone. This, in fact, caused her to answer the phone with a certain edge of suspicious inquiry in her voice when it did ring. The last time Jimmy had gone off on location last year when he went to South America for the outdoor shots of Green Fire, the telephone began to behave mysteriously. It would ring and yet, when she answered, there never would be anyone on the line. She didn’t want that sort of thing to start again this time.

But this time the telephone behaved. And if anything threatened to get out of order, it was Jean. One day she looked out of the window and thought she saw a man down on the road below who was peering up at the house through a telescope. Taking a second look, she realized she had made a mistake. He was a surveyor looking through a transit.

Another time she found herself standing in the living room giving birth to an idle thought that concerned one of Jimmy’s African trophies mounted on the wall—a fine rhinoceros horn. What would happen, she wondered, if she carved her initials on it? And knowing Jimmy, she was able to deduce the answer immediately; she probably would be shot and mounted on the wall beside it.

All this showed that Jean wasn’t enjoying being alone, of course. When you get used to living with a man you have to work at getting used to living without him; it doesn’t happen automatically. Jimmy knew this, too. He had known it when he left and had managed to leave a lot of himself behind in a certain way. For instance, he had suggested that she go on a shopping spree after he left. He said he thought she should pick up a lot of sports clothes.

She did. She went to her favorite store and bought herself a slew of slacks, sweaters, shirts and accessories. But even as she went about selecting the very first article, she thought of Jimmy and what he would think of her choice, and she realized that he was going to stay right there in her mind with every purchase she made. Because he had always shown fine judgment about what she should wear, had in fact picked most of her clothes, she couldn’t very well even buy a belt buckle without wondering what he would say about it.

Had he guessed this would happen when he told her to go shopping? She felt there was no doubt about it and she had to smile about him fondly. He had done more than this, as she now realized.

When they had been in London last winter, they had met one of his favorite painters, Sir Matthew Smith. Jimmy was already an admirer of his work to the extent of five of his paintings, gay floral works, acquired years before and now decorating the living room in their Beverly Hills home. Yet when Sir Matthew said he would like to paint a portrait of Jean, she thought it could hardly be arranged because of their busy schedules. But Jimmy had reworked all arrangements so that she could pose in two sittings—and now that painting, a color and mood impression of her, was hanging in their living room along with the other Matthew Smiths.

It was a portrait of her which she couldn’t help seeing every day. But it was also a reminder of Jimmy, of how much he had wanted the picture, of how happy he was to have his favorite painter put her on canvas.

But even that Jimmy is a Jimmy you have to recall, not a Jimmy in actuality, and when he had been gone for some time, her days began to slow down. The thing to do was to go out; there were many “friends of the family,” so to speak. Yet six weeks after Jimmy had gone Jean had been out only twice, both times escort-less, in the proper sense of the word.

On the night of the Screen Writers Guild Awards Dinner she had gone along with Mr. and Mrs. Mankiewicz, the Danny Kayes and the Bert Allenbergs. She had a wonderful time listening to the clever satire of the men who wrote filmdom’s stories—but perhaps not so wonderful as she would have had had Jimmy been along. He liked good writing, and he liked the viewpoints of writers on matters of the world. She enjoyed these things more seeing them through his eyes.

Her second time out was a visit to Liz Taylor in the hospital when Liz’ second child was born. And this had been the occasion when she had become a godmother for the first time in her life—to Christopher Edward, the Wildings’ baby boy.

But after that she turned down the many invitations and decided to concentrate on her work. There were several demanding aspects about her role in Guys And Dolls. It would be in production for four months, so that she would be busy on it for almost the entire time that Jimmy was to be away. It was a picture on which she had to study almost every night to make sure she was “up” on her American accent.

Once before, when she co-starred with Spencer Tracy in The Actress, she had had to make sure she was speaking American, American as it was spoken around Boston, two generations ago. However, there was at least a token similarity between Bostonian English and British English. But the Broadway version of English, of the lingo as spoken in Guys And Dolls, was something else again.

And so, as this is written, Jean Simmons is spending her time away from the set practicing the lines she has to speak on the set. And outside of this she has given up all other activities except one, which involves a present Jimmy gave her about a year ago—a .22 calibre rifle.

When she finds time, Jean goes out on the grounds in back of her house and practices shooting at a standard small target, about twelve inches in diameter, from a firing point thirty-six yards away. She has decided that she wants to be a good shot.

Anybody who knows Jimmy knows that he plans to go to Africa again soon to do some hunting. Before this he has gone alone. But he did agree that if Jean were a good shot she might come along. Just about now, Jimmy will be receiving something in the mail in Pakistan that will convince him of Jean’s fine marksmanship.

It won’t be a letter. Jean may never get around to writing. Instead it will be a target in which the whole bull’s-eye center is shot away. Jean put seven out of ten bullets into that bull’s-eye. And now she is content to wait for Jimmy to get back. For the next time he goes, she goes, too!

THE END

—BY NATE EDWARDS

It is a quote. MODERN SCREEN MAGAZINE JUNE 1955