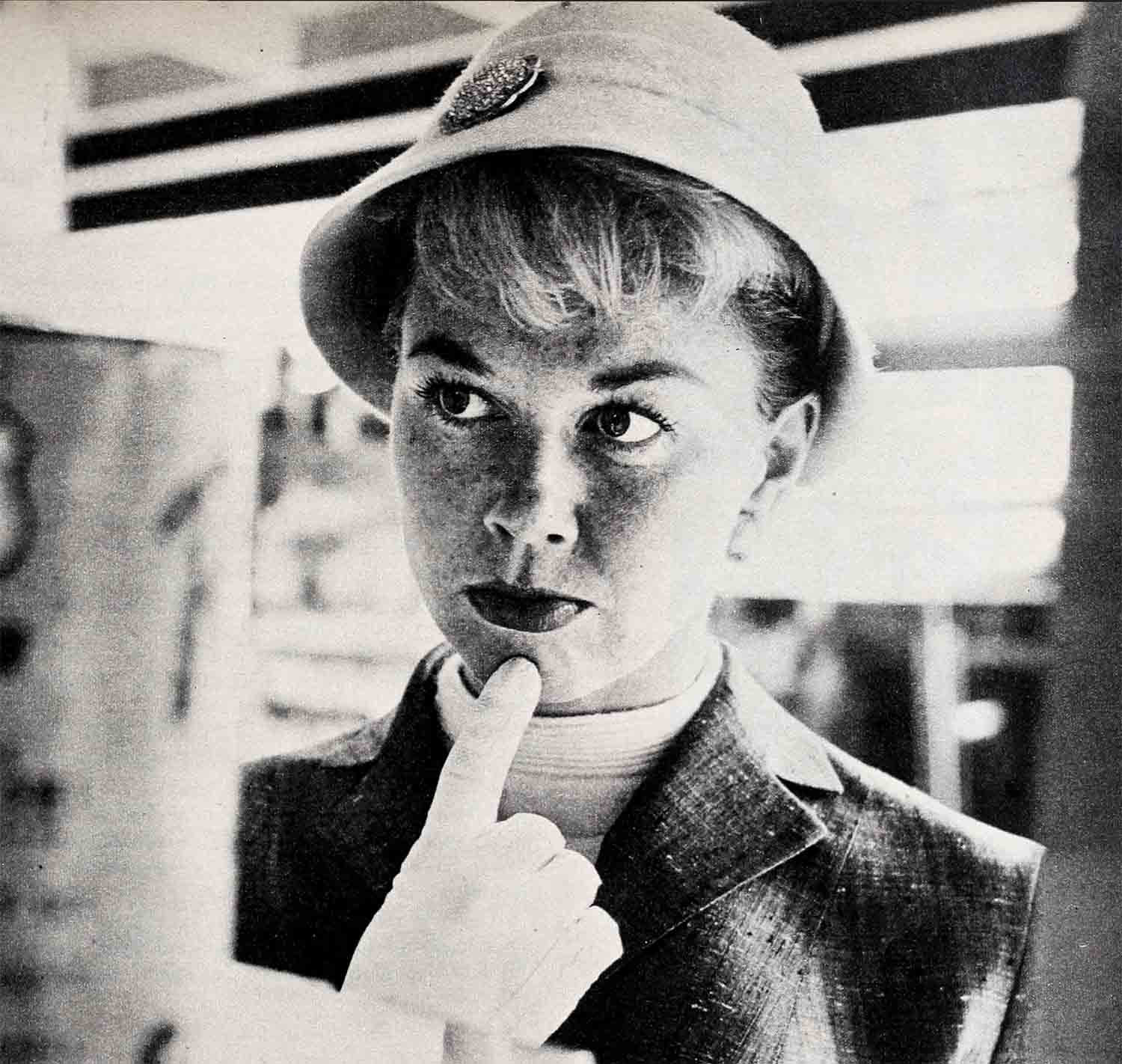

Doris Day: “Gosh, I’d Like To Be Different”

Her big eyes started to brim over with tears. She didn’t want to cry, not in front of everyone, so she tried to hold them back. If only her girlfriends would come! Why did Joanie and Mary have to be so slow? She waited for them in the dimming afternoon light, standing by herself, in the long hall of their high school, “near the statue of Abraham Lincoln by the front door,” where they agreed to meet. She’d been waiting ten minutes. Two tall, lanky senior boys came down the hall. As they passed, one turned and said to his short pal with eyeglasses, “Not bad, but a little hefty.”

AUDIO BOOK

Although he didn’t know it, he said it loud enough for her to hear. She was stunned for a moment; hurt by his wisecrack. If she waited any longer, she’d burst into tears so she walked out of the school building. The curving cement walk with its gleaming patches of wetness from the rain that had fallen earlier in the day seemed like miles. Her breath was a puff of white on the chilly air. She breathed deeply: trying to control the tears welling inside her until she got home.

She walked alone, something she hated to do, wending her way through the groups of laughing and chattering kids. She walked with her head down. She was so glad it had already grown dark because it was harder for people to see her, to recognize her. She didn’t want anyone to say hello. If they did she wouldn’t know what to say. She didn’t want to talk. All she wanted was to go home and lock herself in her bedroom and cry.

When she rounded the corner, she ran the last two blocks to their small two-storied yellow clapboard house. Her aunt was giving a private music lesson and her mother was still out shopping.

She went in by the back door. She hoped her aunt would be too busy to notice.

The light was on in the blue and white kitchen with its old iron stove and high wooden cupboards. Soon as she opened the door, she heard the gliding strains of piano music from the front room. She was lucky. Her aunt was teaching the piano to one of her students. Slowly, uncertainly, the pupil played the sad notes of the wistful tune, “Souvenir,” and the lovely music dissolved her. She closed the back door quietly, sniffling from the tears that ached to be released, and she tiptoed through the carpeted hallway to the mahogany stairs in the hall. One of the floorboards squeaked under her feet, and her aunt, whose sensitive ears never failed to hear even a barely perceptible noise, called out, “Honey, is that you?”

She swallowed hard and tried to speak. “Yes . . .” she said weakly, her voice muffled and trailing. Then she ran up the stairs, ail buttoned up in her fitted brown woolen coat, bright red mitts and her rain galoshes. Once in her room, she breathed a sigh of relief. She closed the door and she fell across the white chenille bedspread, burying her face in the fluffy chenille and letting hot tears stream down her cheeks.

Finally, lying there on the soft bed in her coat and gloves and boots, listening to the piano lesson continuing downstairs, her tears stopped. The February night had blued the window panes in her bedroom. She got up and took off her coat, snapping on the overhead light.

Timidly she stopped, walked over to the long oval mirror with the dark wood frame above her dresser. She stood before the silvery looking glass, staring at herself in her yellow slipover sweater and pleated plaid skirt, turning to the right, then to the left.

Her heart thumped loudly. The heartbeats seemed to say you’re getting fat, getting fat.

She had gained some weight, she admitted reluctantly to herself. She’d known this already from the way her clothes fit around her waist.

She stooped over and unzipped her boots, pushed them off and then went to her mother’s room where she lighted the dressing-table lamp and weighed herself.

There it was, the awful truth, the black and white of her fear. She had gained ten pounds.

“You,” she said, staring unflinchingly at the arm’s length image before her, “you’re going to change. You’re going to be different.”

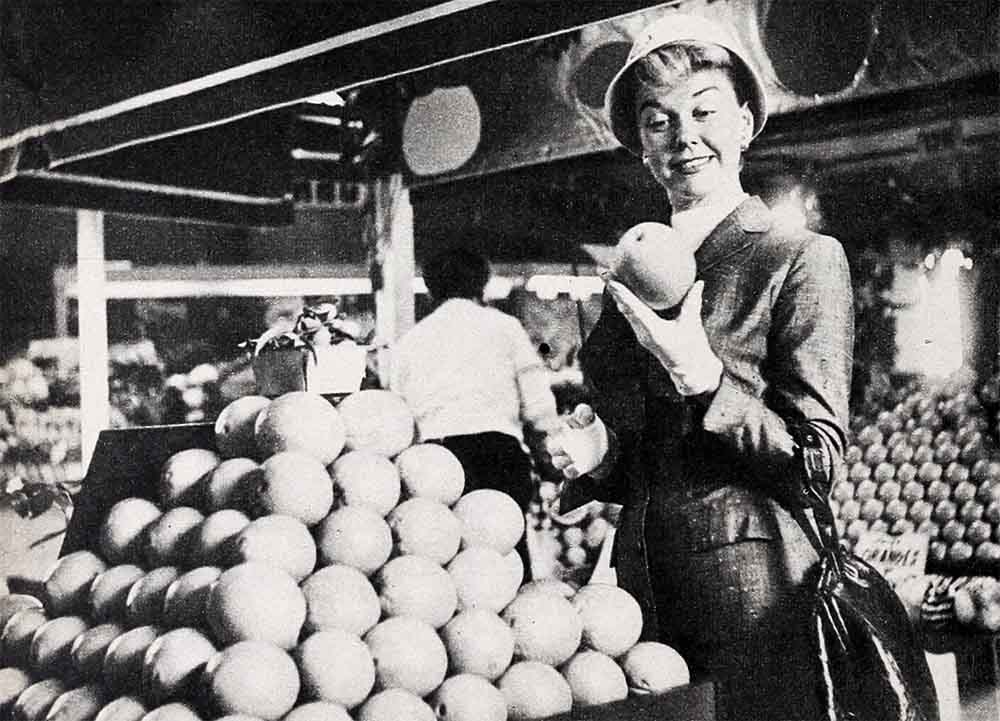

And did she ever change!” Doris Day laughed. We were walking through Farmer’s Market, sniffing at the sausages and cheeses, admiring the bright reds and yellows of the fruits, and then suddenly there we were talking about diets. “That girl was Molly Bee,” Doris continued “Have you seen her lately? She has the cutest figure.”

“Molly told me that day changed her whole outlook on life. Why? She began looking after herself.

“Believe me,” she said, “it wasn’t easy. The hardest thing in the world is to make yourself realize you’re ready for a change. It’s so much easier going along at the same rutlike pace you’ve gotten used to. But when something happens that turns your world upside-down—like that senior’s remark with her—you begin thinking, ‘Oh-oh, something’s wrong!’

“Isn’t it terrible that most of the time something upsetting like that has to happen before you begin to look at yourself from a new point of view? But looking at yourself is only the beginning. Then you have to start making the change.”

The day after Molly made her big decision to be different she was, she remembers, a total flop in her sudden changeover program.

Molly’s mother used to bring home paper bags of little cookies or white boxes of chocolate eclairs or cinnamon buns, and every night Molly would dig in and satisfy that terrible sweet-tooth craving. Later in the evening when she was doing her homework and listening to dance music on the white desk radio in her rose-painted bedroom, she’d nibble on the cookies and drink a couple glasses of soda pop.

The evening after she made her decision to change, Molly decided she wouldn’t eat any sweets or have any soda. She didn’t even want to look at them. But when her mother arrived after six o’clock with her bag of bake shop cookies, Molly couldn’t take her mind off them. Finally, she ended up eating more that night than before because the thought of giving them up made her hunger for them all the more. She drank the soda pop, too.

“Maybe it was just as well,” Doris says, “that she did . . . because she felt terrible. When she went to bed she tossed and turned and couldn’t sleep. She felt she had broken an important promise to herself and she just felt awful, so guilty.” The next morning Molly went to school and during her Home Economics class, along with her classmates, baked a batch of butter cookies under the young Home Economics teacher’s supervision.

“I probably looked so miserable the teacher figured something was the matter,” Molly remembers. “I kept staling at the cookies on my plate, afraid someone would notice I wasn’t eating them. The girl next to me finally said, ‘What’s the matter? Aren’t you hungry? They taste so good.’ ” And she bit into another one. Molly just shrugged her shoulders. When the teacher came over and said, “Molly, don’t you want to try the cookies?” she told her no. She said she’d take the cookies home, that she didn’t feel very hungry right then. The teacher seemed to sense that something was wrong and she looked so sympathetic Molly went back to see her after school. She explained how she had gained weight, that she wanted to go on a diet. She couldn’t have been nicer She gave her such encouragement. She agreed that overweight wasn’t healthy for anyone, and then she sat down and worked out a food plan with her that Molly’s never forgotten—with lots of salads and fresh vegetables and broiled foods.

That was only the beginning, Doris says. The Home Ec teacher warned Molly against some of the diet pitfalls and stumbling blocks she would run into.

“The first thing she had to learn was not to be afraid to say no. This is the hardest thing of all,” Doris says. “Of course, she wasn’t on a starvation diet, but she had to cut down on starches and sweets and all those in-between snacks at school. Well, after school, a girlfriend would sometimes offer her a candy bar, and she’d say she was dieting. And the friend would say, ‘Oh, come on, just this once! One little fudge bar won’t hurt you.’ After she gave in a couple of times, Molly decided all the worry afterward just wasn’t worth it. She decided she’d sooner lose the fun of a couple of bites on a candy bar and say no to her girlfriends rather than torture herself for hours later because she goofed on her food plan.”

But losing weight, Doris says, is a slow process and doesn’t happen overnight. Anyone who intends to stick to a diet must have a storehouse of patience. Doris also adds that if a girl is more than ten to fifteen pounds overweight, she shouldn’t consider a reducing food plan unless it’s been approved by her family doctor. In fact, it’s a good idea to check with him first in any case.

Gradually. Doris says, as those first results begin to show and the clothes don’t fit so tightly around the waist, then the sweet music of compliments makes itself heard and the spirit really takes wings. The effort is worth it.

“When your girlfriend tells you you’re beginning to look thin, that you look so much better, it is like listening to a serenade after all those weeks of saying no to chocolate cakes and lemon meringue pies.

“When you cut down on sweets, by the way, this meant cutting down on chocolate of all kinds. Cut out fried foods because of the grease they’re cooked in. It’s so fattening! And your complexion will begin to look better, clearer. When Molly told her Home Ec teacher all about this, she told her that was only the beginning. Molly didn’t know what she meant then, but later on the dawn came!

“With dieting you gain new respect for yourself. Suddenly you become proud of yourself because you’ve had the daring to become a new you, to be different from the everyday person you’ve been. Not only do you get slim, but you feel happier, and your personality, I’m convinced, shows it. After Molly went on that diet, she had no trouble getting dates. She was so peppy! All of a sudden she felt so much more alive!”

Besides dieting, Doris recommends exercise. You can try exercising alone in your bedroom—doing simple stretching exercises selected from the magazines.

“But misery loves company. You just feel so icky and stupid sometimes moving your arms around all by yourself.

“Why not tell your girlfriends about it and ask them if they want to get together and have a daily session. You could take turns at each other’s houses, and play pop records and really go to town with the one-two-three-fours,” suggests Doris.

“Exercising’s a habit I follow to this very day,” says Molly. “I told some kids in my neighborhood not too long ago to get a One-Two-Three-Four Club started, and they followed my suggestion. I also suggested they get one of the teachers to give them a diet list. Well, in two months, these gals lost anywhere from seven to fourteen pounds! Isn’t that terrific? They said they exercised to some of Doris’ records, especially ‘Instant Love,’ which they like because it’s bouncy. But their favorite exercise record, they said, is Elvis’ ‘All Shook Up.’ Sounds like a mighty good one to me.”

Just as important as exercise, Doris says, is rest. A good night’s sleep nourishes the body. One thing, though, that’s been bothering her all these years is the fact that she can’t get the hang of catnapping. Everyone she knows seems to be a past master at it. But no matter how hard Doris tries to take a quick nap in the middle of a day those forty winks just won’t come.

“I see my mother doze off like that—for five minutes—and get up refreshed, and all I can do is wish I had the knack. Right in the midst of fixing a hem or mending a sock, she’ll curl up on the couch and close her eyes, get up a few minutes later and say, ‘My, do I feel good—just like a million dollars!’ If anyone’s got any suggestions, I sure wish they’d pass them along.”

—LORRAYNE JO GREER

DORIS MADE “TUNNEL OF LOVE” FOR M-G-M AND WILL BE SEEN NEXT IN “THAT JANE FROM MAINE” FOR COLUMBIA, “PILLOW TALK” FOR U-I, AND “ROAR LIKE A DOVE” FOR U.A.

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE MARCH 1959

AUDIO BOOK