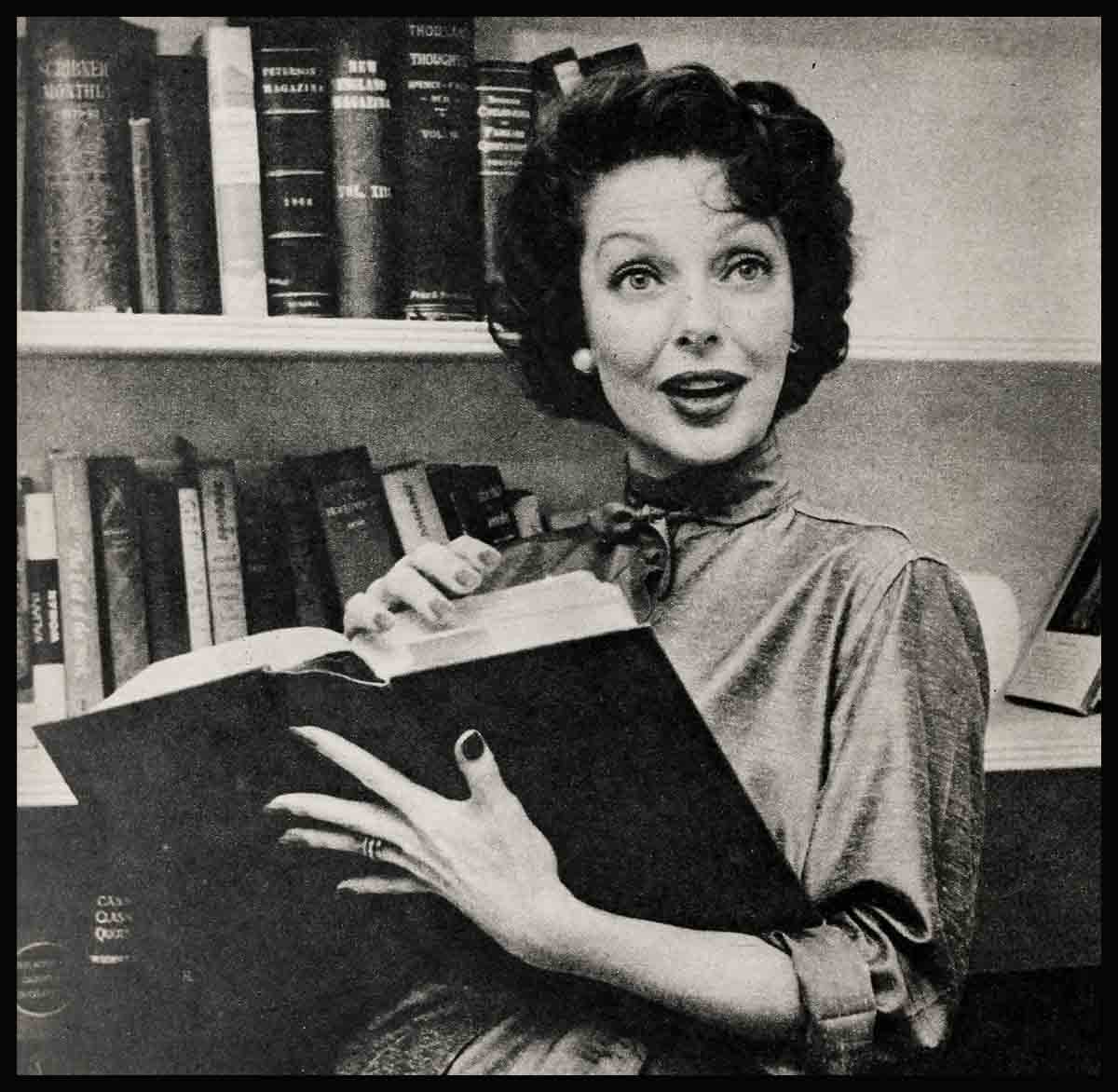

Her Heart Knows—Jane Powell

The Tiny, honey-haired blonde strode into her hotel suite, passed through the sitting room and bedroom without so much as a glance about her, and quickly threw open the bathroom door. Then she let out a squeal of delight at sight of nothing more exciting than ordinary bathroom scales. Tossing a triumphant but mischievous grin over her shoulder at the tall, attractive young man who followed, she kicked aside her shoes and stepped on the scales—all five feet, two inches of her. They registered ninety-nine pounds.

But they registered far more than that, for the pretty young girl was Jane Powell, and the smiling young man was her husband, Geary Steffan—and bathroom scales happen to be a mute but potent symbol of the happiest marriage in Hollywood’s “Younger set.” They represent the time Geary laid down the law.

And, while Jane Powell can afford to buy mink coats she can’t buy any scales for her pretty Brentwood home. Because Geary won’t permit them.

“When Janie and I first started going together she always was worrying about her weight,” he explains. “She stepped on the scales first thing in the morning, last thing at night and at intervals during the day. For a youngster who seldom topped 102, it seemed pretty silly to me. If she gained an ounce she worried about it. A pound extra would bowl her. over. If she drank a milkshake, she couldn’t enjoy it for wondering how much she would gain. Maybe all tiny people are like that, because a few pounds can make a difference, but I told Janie I wasn’t going to put up with that nonsense, and before we were married I said we would never have any scales in our house. And we haven’t.”

So, way back more than two years ago, Geary let it be known that he was going to lay the law down about anything that fretted Jane. And Jane just loved it.

Jane and Geary have not found their happiness by any set of rules. As Jane says, “We didn’t enter marriage with divorce and failure in the back of our minds, so we don’t hold it before our eyes as a pitfall to avoid.”

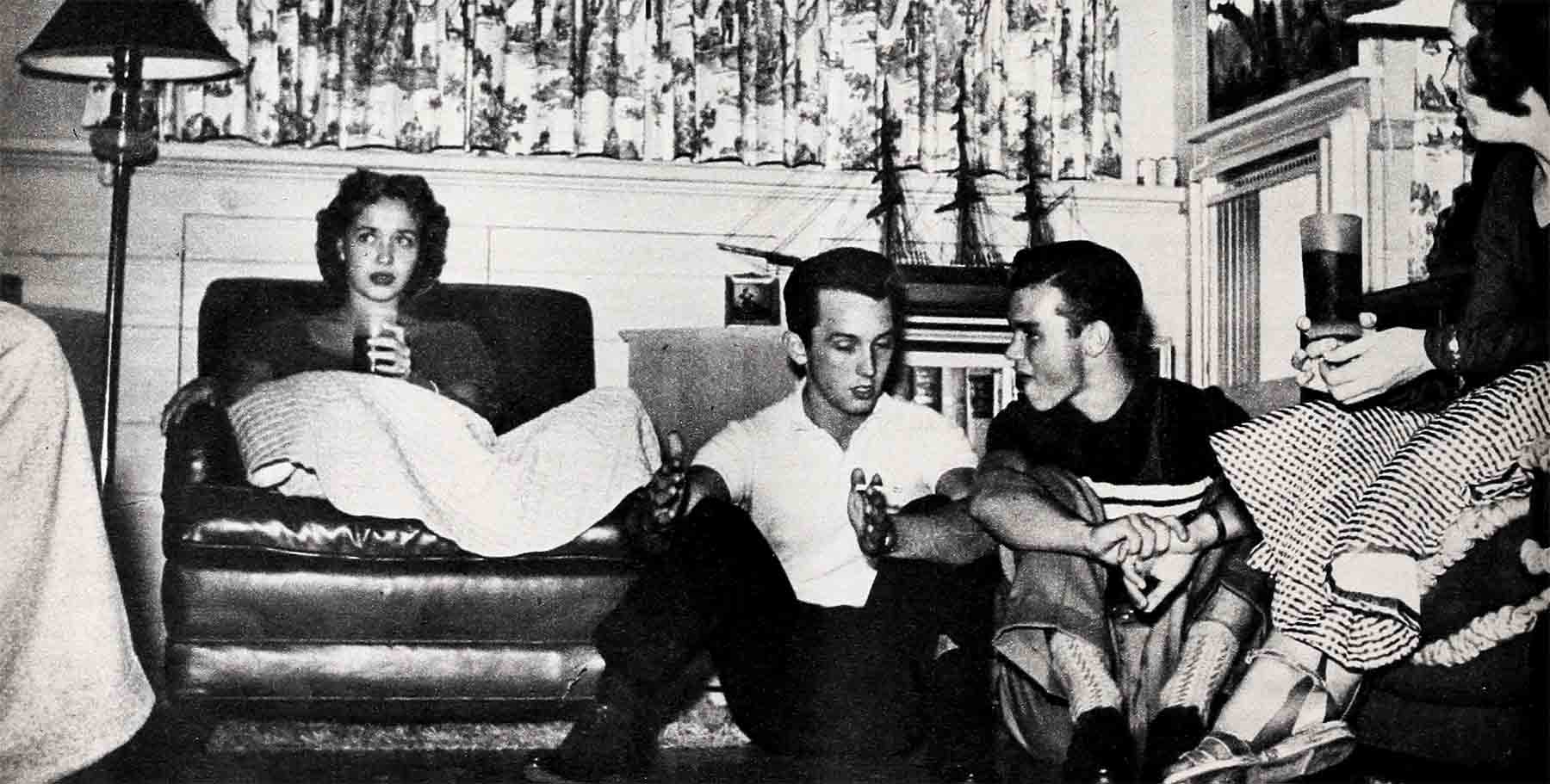

She’s the least star-like person imaginable. Not long ago a small group was sitting around a hotel swimming pool cabana. Bill Pawley Jr., a good friend whom the Steffans inherited from Elizabeth Taylor, joined the party and was reminiscing with one of the men about wartime flying. Others at surrounding cabanas were gazing at the group and Jane told the two men, who were talking rather loudly:

“Say, you two fellows are attracting plenty of attention. Everybody else must be as interested as I am.”

I looked to see her kidding grin, but there wasn’t even a glint in her eye. She was so fascinated by their stories she sincerely believed that was what attracted others from near by.

Jane never had any burning ambition to be a movie star. She has a glorious voice that she has been using since her mother first arranged for her to take voice lessons—almost as far back as she can remember. Then she was sent out to use that voice on radio and in public appearances back in Portland, wherever she could make a dollar to help pay for the lessons. It was a circle that kept her too busy to indulge in a doll-playing childhood. But she has no regrets.

The failure of her parents’ marriage—they divorced two years ago—strengthened Jane’s desire to build her marriage so firmly it will last forever

“I’m glad my mother had ambitions for me, because I certainly had none for myself—and yet I’ve loved every minute of what it’s led to. I like to sing. I guess it’s part of me, even if my job is a lot of hard work.”

When on tour in personal appearances, Jane has no maid to help her dress or to do her hair. “I don’t have a personal maid at home,” she says, “so why at any other time?” She’s never been spoiled, even if she was an only child, because the family of a Portland, Oregon, apartment house custodian has little money for pampering.

“I’ve always worked,” she says, “I don’t remember when I wasn’t working. I was singing on the radio back home in Portland when I was nine. Before that—” her voice trailed off.

She doesn’t want to say anything that would hurt or embarrass her parents, who were divorced two years ago, just after her marriage to Geary. She adores them both. Undoubtedly the failure of their marriage strengthened—subconsciously at least—her desire to build her marriage on such a firm foundation that it never would topple.

She very definitely doesn’t like to talk about her childhood when she earned the cost of her voice lessons by working for the residents of the apartment house where her father was employed.

She ran errands for the parents of the other children, and children can be cruel. Many times, delivering a package and looking in on a tea party to which she hadn’t been invited, she must have been hurt. But this she doesn’t talk about.

Geary says her background has helped to keep her feet firmly on the ground. And now, when she has everything, she hasn’t forgotten what it means to have so little. If she should ever forget, Geary will be there to remind her.

“I didn’t know Jane when she was a little girl,” he says, “but I do know how hard she worked doing things for other people. I know, too, how little she had. I think that’s one reason she is so sweet and considerate. She is also very sensible, naturally. And should she ever get cocky, I’ll be there to take her down right quick.”

Geary’s indispensable to Jane and she knows it. So much so that at first she was miserable when he left her. The first year of their marriage, therefore, had its little ups and downs. But the world never heard about their quarrels because they never occurred in night clubs, and Jane never went heme to Mama.

Jane isn’t perfect, you can take both her and Geary’s word for it. And neither is he. He likes to play tennis. So Jane is often a tennis widow. At first it irked her.

“Janie is understanding about it now,” Geary says, “and doesn’t fume about my going out for a few sets of tennis with the fellows. She did at first. I’d tell her to come along, if she wanted, but I knew she didn’t. She’d want to know what time I’d be home, and I’d say, ‘Oh, around two o’clock,’ going out about ten in the morning. Well, you can’t tell about those things so maybe I wouldn’t get in until four o’clock. Then she would be mad. But I soon made her see that recreation was important to me, and that no marriage would last if a man turned namby-pamby. Now, when I play tennis, she is busy about the house and with the baby and I don’t think she even misses me.”

Also Jane loves to cook. And Geary likes to eat. So this is another important contribution to their marriage. Like all good cooks, she likes to experiment with wines and sauces—and like most American husbands, Geary often fails to appreciate the mystery of the cuisine. It hurts, but he tells her. And she files that dish among her souvenirs. When he does enjoy a dish, which is more often the case, he tells her too. And you should hear him brag about her souffles when she isn’t around!

There were numerous other difficulties to iron out that first year. Jane is sensitive, a hangover from childhood, and sometimes feels a slight when Geary is sure none is intended. Once she came home highly critical of a fellow worker and, pouring out her accusations to Geary, she waited for the words of sympathy that she felt sure would follow.

Instead, Geary told her quietly, “You never knew this person before. That’s probably just his way of talking. You don’t like it. Well, there may be something about you that he doesn’t like. Let’s have this guy for dinner and play a game of looking for his good traits.”

Today, this man is one of their good friends. Together, they’ve worked out a system of finding something pleasant in the seemingly most objectionable people. And a couple who practice looking for good in others must apply the same method at home—and so avoid that road which leads to divorce courts.

By this time everyone knows that the happiest reason of all for Jane and Geary’s happy marriage is little Geary Steffan the third, who will be one year old in July. Jane sings him lullabies and she tells him about the four more little Steffans who she and his daddy hope will share his nursery within the next few years.

Always when Jane talks about the family she wants, a wistful note creeps into her voice. “I was so lonely,” she says. “I remember begging my parents for a sister to play with—or a brother.” Geary supplied this need for Jane, too, for marriage to him gave Jane two sisters. It was while visiting in the home of his married sister that she and he learned to know each other so well.

“We were engaged for eleven months,” Jane recalls. “We knew so much about each other when we were married that we were spared a rude awakening. Our marriage was more of a transition. We danced together, skied together, tobogganed and skated together. Geary even ate my cooking before we were married. If I advocate anything for a successful marriage, other than being in love, it’s an engagement long enough for two people to learn all about each other.”

Geary, of course, had to learn that—married to a celebrity—he must make adjustments. Fortunately, he was familiar with the entertainment world and so realized the demands that are made on a star. For before Geary married Jane he was an ice skater. Wisely, he turned to a business career, opening his insurance agency.

They own their home jointly with all of its contents. Each month they contribute to their far-from-lavish Brentwood house-hold—run with one maid, Gladys—on a fifty-fifty basis.

“Nobody ever can say that anybody carried me,” says Geary proudly. However, he is sensible enough to know that a movie star is required to dress like a movie star. He adds, “Whatever Jane wants to do with her money after we divvy household bills is all right with me. If she wants to spend $5,000 for a mink coat, I don’t care, but she can’t spend five cents more on the house than I do.”

Jane Powell was a pert young miss of twenty who was doing all right when she met Geary Steffan, but to hear her now you’d never even know it.

“Since I’ve been married to Geary I’m calmer, quieter, and have a lot more poise. I used to talk too much—just prattle—and never say anything. Now I don’t talk unless I’ve got something to say. He made me realize it was nervousness that makes people talk too much and act gay and life-of-the-partyish when they just want to sit and listen and relax sometimes.”

What Geary has given Jane, of course, security and serenity, are things that money can’t buy; such things as keep escaping the Lana Turners, Elizabeth Taylors and many others in Hollywood.

Geary also has given Jane a feeling of religion. When other little girls were raising their voices in Sunday school choruses, she was raising her beautiful young voice over radio and on stages—for pay.

“Every child should have some religion in his or her background, but I had none, was connected with no church,” she says, wistfully. “I went to different churches as I grew older but that’s not like belonging.” And she added with determination, “Our baby will grow up in a church.”

Geary is a Catholic and he and Jane were married at the Church of the Good Shepherd in Los Angeles.

They started out their married life, as so many young couples do, in a small apartment, with Jane doing the housework. She didn’t have to, of course, but it was fun, and she felt closer to Geary that way. When they knew their family was increasing, they moved into their own home, and Jane got Gladys, “a real jewel,” to help her.

“I’m so lucky to have Gladys. She’s a wonderful cook, maid, nurse, housekeeper rolled into one, and how she loves the baby! When Geary and I went to Miami Beach last December, where I sang at the Copa City, Gladys was tickled to death to get me out of the house, so she could have the baby all alone.”

Since the Steffans don’t have a “regular nurse” they get up themselves at night with the baby, but they don’t spoil him.

“We get up and look at him and if there’s nothing wrong, we let him cry, which isn’t often,” Geary says with parental pride. Thus, they prove again that theirs is an old-fashioned marriage, based on old-fashioned methods, for the most modern way is like the old way, to pick up the baby and comfort him if he cries.

Janie’s and Geary’s friends are not among the glamour set of Hollywood. And they are not ringside habitués at smart night clubs, even though they like to dance and have their nights out just like young couples everywhere.

But there seems to be more time for everything for Jane now that she’s a wife and mother and a bigger star than ever. She has found, through her pleasant, easy way of life with Geary, that there’s really no need for hurrying about everything.

“I’m inclined to be impatient, to want everything done at once. Geary never is in a hurry,” she laughs, adding, “but he always gets things done.”

“Janie was a long time learning that, but it finally soaked in,” he kidded her. “When she wants a rug moved or a lock fixed or the baby’s diaper changed or anything else—”

“Well, the baby’s diaper—” Jane interrupted—

“—must be changed, I know,” Geary granted. “But it never hurt the other things to wait a few minutes. I just don’t like to hurry. And Janie is learning.”

Above all, they’re both considerate of others. Once, a young entertainer, with far less of the world’s goods than they, asked them to go deep sea fishing. They accepted and agreed to share the cost. When rough waters appeared likely the day before they were to go out, Geary, telling Jane he was afraid she might be seasick, suggested they should cancel their plans. Jane agreed, quickly adding, “Has he made a deposit on the boat? Will he lose anything?”

“I’ve already taken care of that,” Geary assured her with an affectionate pat.

Unlike so many who no longer have to worry about money, Jane remembers that others often do, explains this cheerfully, in fact, by asking, “How can I forget—when I was poor much longer than I wasn’t?”

That’s Janie. She has the infinite wisdom a woman knows when she listens to her heart. Otherwise, reacting unhappily to the unhappy things that have happened to her, she would have matured with less of all the qualities that have won her stardom and Geary Steffan and the good life she loves today.

THE END

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE APRIL 1952

No Comments