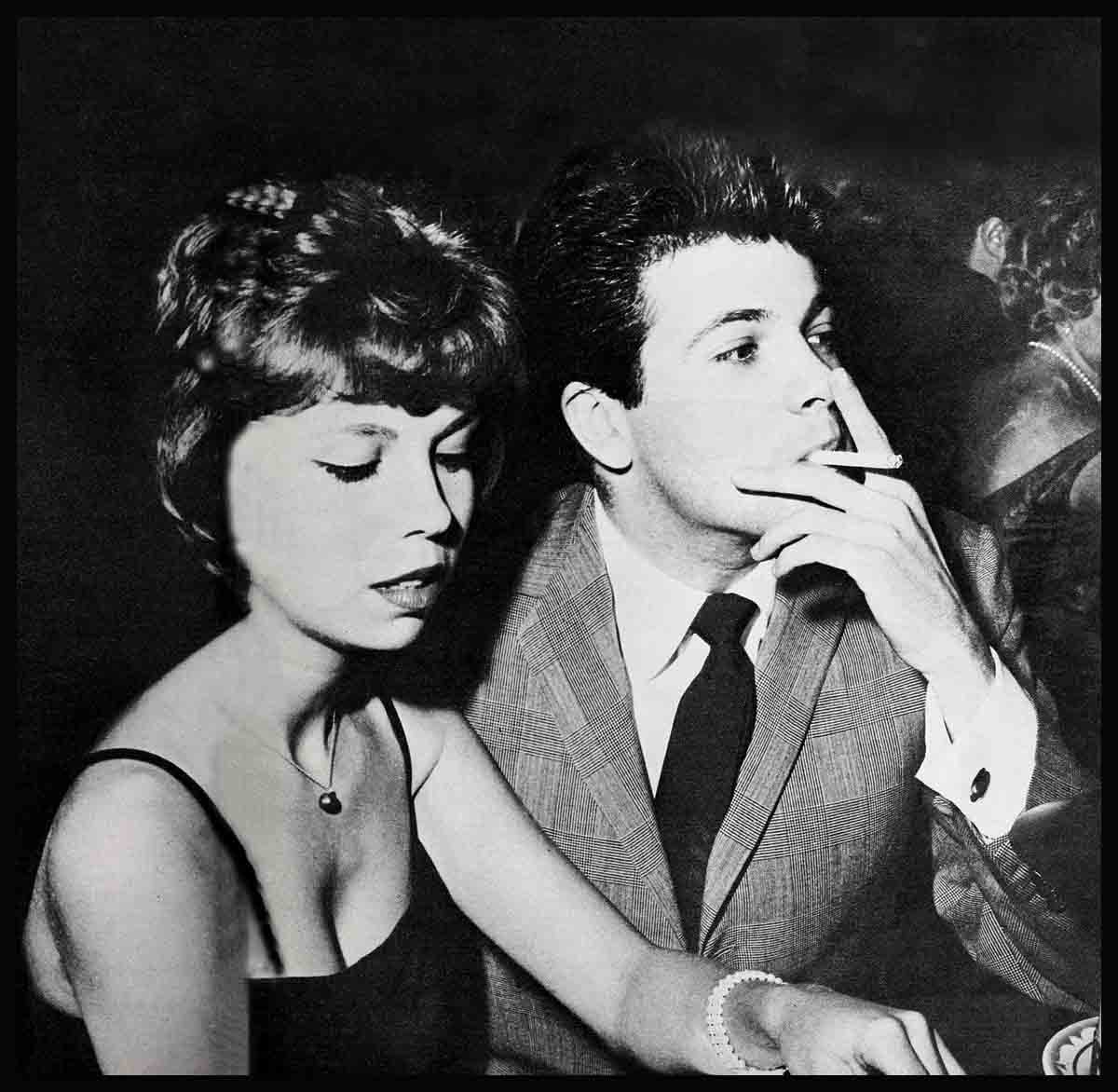

Tommy Sands Vows: “I’m going to marry Nancy Sinatra”

Tommy watched the cigarette burn, knowing that when this was finished, he couldn’t put it off any longer. He and Nancy would have to leave the restaurant and walk over to the ABC studio where her dad, Frank Sinatra, was rehearsing his show. Nancy knew he was scared. That’s why she was so quiet as they sat waiting for the check. Tommy had known Nancy for just over a year and he’d been going steady with her since Thanksgiving, but he’d never really met her father.

Once, a friend who knew both of them, had introduced Tommy and Frank, but it was so quick that Tommy hadn’t had a chance to say more than hello. Since then, they nodded when they passed each other in a restaurant or there’d be a brief handshake at some crowded Hollywood parties. But never more than that.

And now, Tommy wanted to marry Frank Sinatra’s daughter. He had a tight, nervous feeling deep in his stomach, and his hand shook a little as he put the money, for their dinner, down on the little tray the waiter had brought with the check.

Nancy reached over and touched his arm lightly, and it helped, the way it always did. “I’m going to marry her, no matter what,” Tommy told himself . . .

No Bells Rang

And yet their first meeting had been so casual. No bells had rung and there’d been no blinding flash of love-at-first-sight. A year ago, Christmas, some friends had taken him to a party at Nancy’s house. And then, last August, when he’d opened at the Cocoanut Grove, she’d come backstage with a group of friends and they’d met again.

It was a Saturday night and lots of people were crowding into his dressing room, but there’d been time for her to say, “I really like the way you sing, Tommy,” and he’d taken her hand and held it for a moment. Afterward, Tommy turned to a friend. “She’s real cute,” he’d said. “I wonder if she’ll go out with me.”

“Not a chance,” his friend answered, shaking his head. “She’s taken. Everyone says she and Jack McGiveney are going to get married.” Tommy said “oh,” and thought to himself that it was always like that, that it was too bad the way the cutest girls always got snatched up so fast. But he was pleased that Frank Sinatra’s daughter had come backstage to congratulate him. When he was getting ready for his opening, he had spent the day before playing Sinatra records to himself for hours.

It was just before Thanksgiving when Tommy heard that Nancy and Jack had split up. He called two of his friends, Eddie Goldstone and Bill Belasco, and they got Nancy’s phone number for him. Then he called her and she remembered the time they’d met. She said, yes, she’d go to a party with him.

Driving to the party, and for a while after they’d arrived, Tommy and Nancy were both rather quiet. Tommy doesn’t open up with people until he’s known them for a while and Nancy, too, has a kind of shy reserve at first meeting. After a while, they found themselves sitting off in a corner alone. They were listening to the record player when Nancy started to talk about music. She told Tommy she’d even thought about a singing career for herself. She’d taken acting lessons, too, and couldn’t decide between the two. Tommy told her about the songs he wanted to write, about how his father wrote songs, too, but how he never sang any of them. By the time he pulled his car up in front of Nancy’s house and they said goodnight, they were talking more easily with each other.

A few days later, they had their second date . . .

“If Frank Sinatra had any objections to Tommy Sands,” a friend very close to the family said, “the boy wouldn’t even have been allowed to phone a second time.” Tommy knew that was true. He also knew that Frank had always kept a close eye on his daughter. Nancy had told him that somehow her dad always knew when she’d stayed out too late on a date and that he always called her the next morning to scold her about it.

Frank hadn’t objected to that second date. But still, now that he was to meet Nancy’s dad, Tommy had an awful sinking feeling. Now that it was a question of marriage, Frank might feel a whole lot different.

Lying in bed, the night before, Tommy tried to think what Frank would say when they met. If only he could know that, then he could have his answers all pre-pared. But when he’d shut his eyes, he couldn’t seem to hear Frank saying anything. He couldn’t sleep, so he’d gotten out of bed and slipped on his robe. He’d switched on a small table lamp and begun pacing back and forth. He was often restless like this—particularly before an opening—and lots of times he’d have trouble sleeping. Sometimes, he’d get up and play the bongos and that would relax him.

But this night, he’d just slouched down in the armchair and, lighting a cigarette, tried to think. Some people had compared him to Sinatra . . .

We Both Needed A Friend

Frank was an only child, just as he was, and he’d been frail as a kid, too.

But Tommy had been poor and that had bothered him a lot when he got to high school. The other kids weren’t exactly rich, but they didn’t have to worry about money. Tommy did. He didn’t have the right clothes and he didn’t have money to buy a girl a soda or take her to the movies. He didn’t feel bitter about it, but he was always uncomfortable with the other kids.

He’d needed friends, especially in his teens, when his mother and father were divorced. Tommy understood when his father, a pianist, had to go off on the road and be away from them for long months at a time. That was show business and he understood. He’d been in show business himself, since the time he was eight, playing a guitar on radio. But for his mother, the separations were harder and harder, and eventually there was the divorce.

Not having money then, hurt even more for some reason. His mother had had to work and Tommy knew that she worked hard. He’d always hesitate about asking her for money even for things he really needed like carfare or lunch money. And when he’d found out she was doing without new clothes and, lots of times, even without lunch for herself, he’d question: “Well what does a guy say to his mother when he finds out she’s going hungry for him?” He thought he had had the answer. Just before he was supposed to graduate from high school, he’d quit school to take a job on radio. Later, he was sorry.

Tommy had read stories that Frank was poor, too. But he also knew that Frank said that wasn’t true. Frank’s neighborhood, in Hoboken, was more or less a middle-class section and Frank, like the kids Tommy used to feel so uncomfortable with, didn’t have to worry about money. Frank was an only child and his parents bought him everything he needed. Even though his mother, Dolly, was busy in local politics, Frank had had someone to look after him—his grandmother. He was cared for so lovingly, that the kids nicknamed him “Slacksey O’Brien” because he had so many different pairs of pants.

The “O’Brien” was because his father used to prize fight under the name of Marty O’Brien. Marty had taught Frank how to use his fists, too, and that had helped him to be accepted by some of the tougher kids in the neighborhood, even if he was skinny. Tommy had heard that, even today, Frank liked tough men around him.

Would He Understand?

His thoughts still whirling, Tommy left the armchair and began pacing up and down again. Without even knowing what he was doing, he began to twist nervously at one of the buttons on his pajama top. When the button came off in his hand, he looked at it, surprised.

If only he knew what Frank would say tomorrow. Tommy didn’t think he’d pick on the question of their religions—at least not right away. Nancy was a practicing Catholic, and Tommy had been raised as a Methodist—his mother’s religion—and his father was Jewish. Nancy, herself, had said this difference was “touchy,” but Tommy was sure they could find a way to solve it. He didn’t know how Frank felt about intermarriages, but he knew that he wasn’t prejudiced in any way. The neighbor who’d helped look after him, when his grandmother died, had been Jewish and Tommy had also read of how Frank had walked out of his son’s christening when the priest started to object to his having a Jewish godfather.

Tommy thought, too, that Frank would understand about his having belonged to the “Young Raiders.” Frank would understand about a guy wanting to belong to something.

The Raiders were all young actors and singers and they had fun running around town together. Tommy hoped Frank wouldn’t remember the time Lindsay Crosby, who was their chief, had told a newspaper reporter that Frank Sinatra and his friends—“the Clan”—were getting “old.” For a while, it seemed as though the Raiders were trying to compete with the Clan for headlines, and even for members. Tommy quit the group just about the time he went to New York to study with Actors’ Studio, but he remembered that the Raiders’ biggest crusade had been to try to win Sammy Davis Jr. away from the Clan. He was pretty sure Frank must have just laughed about that. And after all—it was all in fun and just a test of loyalty.

Loyalty was important to Frank; that’s what people who knew him said. Someone had told Tommy about the time Frank was fourteen. His allowance was larger than the other kids’ and he had bought a season’s pass to the Palisades swimming pool. The other kids didn’t have passes, but Frank would go around back and slip his pass to them, one by one, so they could get in, too. One day, the guard caught them at it. His friends ran away, but the guard managed to grab Frank and beat him up. “I got those guys into the swimming pool,” Frank said, “but, when I was getting clobbered, not one of them came to help me. They just—scramsville.”

Were They Too Young?

Tommy looked at the picture of Nancy, on his dresser, and then at the little clock next to it. He saw it was getting late, and as he ran his fingers nervously through his hair, he knew he still wouldn’t be able to sleep.

Were he and Nancy too young? He was 22 and Nancy was 19, just about the same had been when they got married. Although it was true that they’d come from the same town, both from Italian backgrounds, and they’d known each other for four years before they got married. Yet, their marriage had failed. Maybe Frank would say that young marriages were too much of a gamble.

Or maybe Frank would talk about his being a singer. Maybe he’d say he didn’t want his Nancy to be caught in the same kind of show-business marriage that her mother had been.

Tommy could understand some of these objections. He knew that it was asking a lot of a girl to put up with the doubts and insecurities he’d sometimes face. There was that terrible drive he felt, too, the need to keep proving himself. That meant more tension, more nervousness—and more a on a wife to try to understand him.

He still thought his own success had come too fast. It meant he had to live up to it each time he sang after that. He wondered if Frank had ever felt the same way.

When Frank had hit it big, he was once more the boy with the pass to the swimming pool. He surrounded himself with friends. Tommy knew Nancy Sr., today, and he was impressed at how well groomed and dressed she was. But he’d heard she hadn’t always been like that. People said she was basically a home girl, though she’d learned new tricks in make-up and had tried to dress up to her part as Frank Sinatra’s wife.

Still, Frank hadn’t been a success very long before the rumors began to reach Nancy. A friend would call and say she’d seen Frank with another woman or, when the phone didn’t ring, Nancy could read about it in the gossip columns. Sometimes it was true; sometimes it wasn’t. It’s a hard thing for any woman to forget, especially when it’s written in black and white.

Publicity can harm a love. Tommy knew all about the wrong kind of publicity. When he first came to Hollywood, he’d met a girl, Molly Bee, and after a while he gave her a ring, two hearts entwined, because that seemed just right for her. Everybody said they’d get married—and that was just the trouble. Everybody was saying it; everybody was watching them. Tommy knew publicity had to be part of his life, but he blamed that publicity for spoiling his romance with Molly.

He’s never really played the field. For him, it was one girl at a time, and after Molly there’d been a succession of other girls, though none of them could get him started thinking seriously, the way Molly had done. He felt insecure about girls, and he couldn’t help wondering, each time he started to telephone one of them, whether she’d say yes because he was Tommy Sands, the singer, or because she really liked him for himself. Did she want something from him? He’d wonder. He was never really sure.

It was one of the things that made him feel so good about being with Nancy. She was Frank Sinatra’s daughter and that meant she had position, money, that everywhere she went, the doors were open to her. She didn’t need anything or want anything from him. When Nancy and her mother had come to Las Vegas, while he’d been singing there, somebody’d said that Nancy stuck so close to him you’d think they were shackled together. Well, if she did, Tommy knew it was because she liked him.

And Tommy felt the same way. He couldn’t stand to be away from her. He tried not to think about having to go into the Army in May, and the six months’ separation that would mean.

He remembered their last separation, when he’d had to go on tour to sing for two weeks. That’s when he knew, for sure, that he loved her. He’d called her long distance and asked her to marry him. Maybe a proposal over the phone wasn’t the way Nancy had dreamed it would be, he thought now, but anyway she’d said yes. She felt the way he did, too, about getting married as soon as they could. They even talked about eloping. But, then, Nancy laughed and said, “I don’t think we could ever get away with it.” Finally they decided to marry around December. Remembering that phone call, remembering that she loved him, he was finally able to flick off the light and fall into a sound sleep. . . .

. . . And Then He Laughed

Nancy had been quiet on the way to her father at the ABC studio and Tommy smiled at her now, gratefully. She always seemed to be able to sense his moods and then to do just the right thing to help him out of them. He pushed open the outside door and let her go in ahead of him. Once inside the big building, he looked around for some sort of directory which might tell him which way to turn, but, then, Nancy took his arm. “It’s this way,” she said softly. Somehow, her being sure of even such a little thing, made him feel better.

Inside the studio, the big cameras were dollying around to find the best angles and men with earphones on were shouting instructions they’d gotten from the glass control room. Nancy and Tommy stepped carefully over the cables that stretched in every direction on the floor. When Frank spotted them, he waved and began to walk over to meet them. Tommy felt a moment of panic. He’d tried to plan so carefully what he wanted to tell Frank, but now he couldn’t think of a thing to say to him.

Frank gave Nancy a hug and then he shook Tommy’s hand. Nancy could usually tell, just by looking at her father’s eyes, what he was thinking. But she couldn’t read the expression in them now as he said, “Come on over here, Tommy. We can talk better.”

She watched them walk over to one side of the big barn-like rehearsal studio. Nobody could hear what they were saying, not even Nancy.

A friend in the TV crew, started to talk to her and she had to turn toward him and smile and be polite. She longed to turn around again, to try to catch a glimpse of her father’s face. One look, she was sure, was all she needed to tell her what he thought of Tommy. But the man kept talking. She hardly knew what he was saying, she was praying so hard inside.

Then she heard her father’s laugh boom out. It was his good laugh, the one that meant everything was all right. Nancy smiled at the man, but now she really meant it.

Tommy was smiling, too, and Frank’s arm was around his shoulder as they walked back to where they’d left Nancy. “I’m very happy about the whole thing,” Frank said. He waved his hand in a gesture that took in all the cameras and lights and microphones and, laughing, said so that everybody could hear him now, “I’m glad there’ll be another singer in the family, because I’m getting tired!”

—BY MILT JOHNSON

HEAR FRANK SINATRA AND TOMMY SANDS SING ON THE CAPITOL LABEL. DON’T MISS FRANK AS HE APPEARS IN WARNER’S “OCEAN’S ELEVEN,” AND SEE HIM IN 20TH’s “CAN-CAN.” BE SURE TO WATCH AND ENJOY HIS SPECIALS OVER ABC-TV.

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE JUNE 1960