Elvis Presley Was My Buddy In The Army

Elvis married? It really isn’t true. All shook up? We’ve been April Fooling you! A-l-o-n-e and still a-v-a-i-l-a-b-l-e is your El. And ’cause you’re a good sport and take a joke so well—

I guess we were all pretty curious to find out what it would be like having Elvis on base—whether he’d have a private room, whether he’d arrive in a chauffeur-driven Cadillac, whether he’d be greeted by the divisional commander and have special privileges. And I guess if we’d been told the President himself were arriving, it couldn’t have created a greater stir among the fellas.

Oh—sure, to have these sort of privileges did seem far-fetched, but we’d all heard so many outlandish stories about what happened to celebrities when they became soldiers that we were expecting just about anything.

And in many ways we weren’t disappointed.

I remember the day he arrived. I’d been working in one of the offices when suddenly I heard a lot of screaming and shouting. I looked out of the window and sure enough, there was Elvis. At that point I couldn’t actually see him, but by the hollering of the teenagers who were jumping up and down by the bus as it rolled past them into the base, I knew it could hardly be anyone else—and we all knew to expect him that day.

There were cameras, radio and TV announcers, newsreels, and I guess all of us would have liked to have stood around watching if we hadn’t felt it was rather stupid to stare awestruck at a guy who, after all, was just another trooper.

No Cadillac, that was evident, or an official reception, but we were all curious to know what his duties would be and some fellas, who hadn’t been too lucky themselves when they first arrived, took a sour grapes attitude even in the fun. “He won’t get KP,” said one. “Doubt if they’ll even let him get his uniform dirty in case Uncle Sam’s army won’t look neat and tidy,” grumbled another.

“Cut it out,” I told them. “At least give him a chance.”

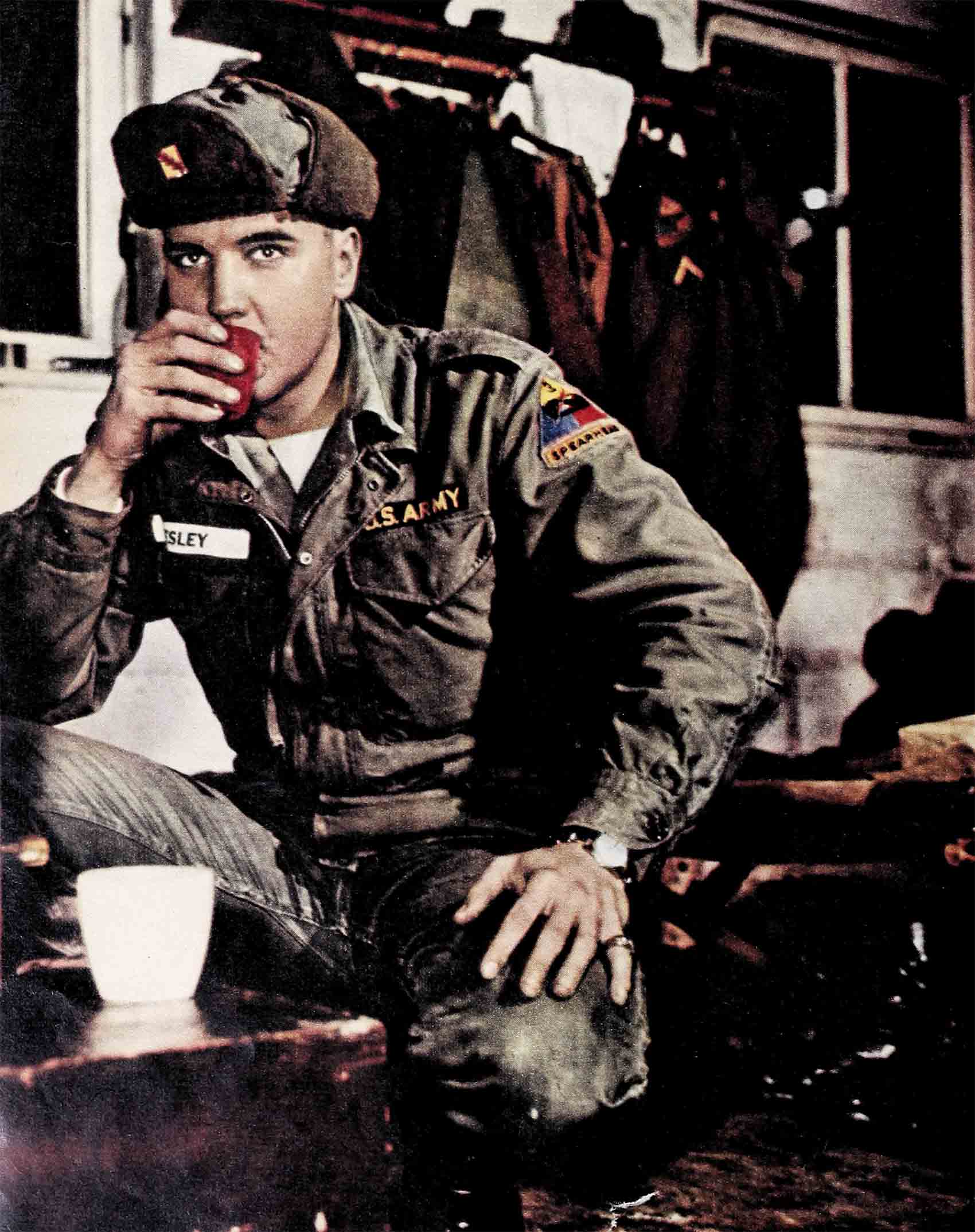

Elvis looked a little bewildered as he got down from the bus and was ushered past us with the rest of his company. He was in the Second Armored Division, like me, and I’d been told he was going to be a truck driver with us. He seemed a nice enough guy and certainly not out to make a show of himself, you could tell that by watching him even for a few minutes. When he got down from that bus he could have easily taken advantage of the situation to draw attention, but instead, he fell into line like the rest.

Those first few weeks I didn’t see much of Elvis as he’d been assigned to another part of base and was out on exercises most of the time Yes, they were letting him make full use of his Uncle Sam suit.

Then one day, I’m pretty sure it was a Sunday morning, I’d gone to the snack bar to get some coffee when I noticed a large line-up at one of the tables—almost halfway across the room, in fact. I didn’t know at first who it was and then a buddy of mine said, “Say—isn’t that Elvis?”

But the boys at our table weren’t really taking much notice of him. They’d been the ones who’d taken the stand that he was just another GI like anyone else.

We must have sat around laughing and joking until almost eleven o’clock—it had been about nine-thirty when we’d first come in—and all that time Elvis was writing out autographs on napkins and pieces of paper guys were handing him, writing without a break. I think they were asking out of curiosity else.

I must admit I was curious to meet Elvis and had been admiring his patience through all the fuss. I had a niece back home who’d been asking me for weeks to get Elvis’ autograph for her so I figured this was as good a moment as any—though I felt pretty stupid asking for it.

I fumbled in my pockets and found a calling card which seemed pretty suitable and, stubbing out a cigarette, I goy up from the table and walked across the room towards Elvis. He had his head bent over and was writing away a mile a minute. I said, “Gee—you’ve a lot of patience,” and he grinned and said, It’s something for their sisters back home. If it makes them happy, why not?”

I put my calling card on the table. “Like me to say anything special on it?” he asked.

“No—just write your name. I think that’s all she wants,” I said. Then I thought for a moment and added, “Oh—you might just say ‘To Linda.’ ”

“OK,” he said and flourished his signature across the card.

As I walked over to my table I looked back and noticed that he was writing so fast that the ink from his ballpoint pen kept drying up and he had to keep shaking it to keep the ink going. From time to time, he would stop and stretch his arm and then continue with the autographs.

“I don’t envy a guy who spends his Sundays that way,” I told the boys when I got back to the table.

“Well—it’s better than shining boots,” quipped one whose boots never seemed clean no matter how many times he polished them.

And we all got up and left Elvis alone. I was on guard duty, a few days later, when I next saw Elvis. I happened to be talking with the officer of the day, who’d come up to give me some orders, when we heard a lot of commotion.

We turned to look along the road. A battalion was returning from training exercises, and at the back of the long file of men we could hear screaming and shouting.

“Must be Elvis,” I said to the officer. We’d already all become quite used to the fuss caused anytime Elvis was around—particularly outside of camp where the teenagers could get near to him.

Sure enough, up the road, looking hot and dusty from a day in the fields, came a tired, dishevelled Elvis.

Kids were screaming, with a rifle!” And others, “There’s Elvis “There’s Elvis with a pack!” If I’d been Elvis I think I might have been a little mad. Because you feel kinda grouchy after a tough day.

But he marched coolly along in line, hardly even turning his head. Then, as he passed us by, I heard him say to one of the M.P.’s walking by his side, “Gee—I’m glad to be back in base.”

“You know,” the officer of the day remarked to me as Elvis disappeared into the barracks, “he’s really a good soldier. I was out with him on rifle practice the other day and he sure was a good marksman—better than average I’d say. And I sure was surprised to hear a barracks buddy of his say he acted ‘just like a man who’d inherited a million’ when they gave him his ‘Hell on Wheels’ insignia. Seemed kind of strange coming from a celebrity.”

“Maybe he’s afraid they might resent him,” I suggested. “So he tries to be especially humble.”

“Maybe . . .” the officer looked thought-into the dusk, shrugged his back, and then walked off.

There was an odd mixture of resentment and real sincere gratitude when the word got around that Elvis was giving several thousand dollars for the re-furnishing of the day room. The day room is the company’s recreation room where they can relax, maybe play a game of pool or watch TV.

I was pleased—particularly because I’d heard that among the new furniture was going to be a twenty-one-inch TV set. And the old set was always going wrong at just the worst moments!

Well, when the day finally arrived for its completion, I think we were all delighted. There was a new coat of paint, re-upholstered sofas and comfortable a new pool and ping-pong table and—yes, the twenty-one-inch TV.

“How can you get mad with a fella who does a thing like that?” I remember remarking to one of my buddies.

“Yeah—and he certainly does bring some new life to the camp,” he admitted.

But the real excitement was still to come . . . the time when we all went into town and Elvis got caught speeding on the way back . . . and then the time when he had the new NCO’s club in an uproar.

That time in town, Elvis, myself, and a few other fellows, had gotten passes and Elvis had his new, brilliant red Lincoln convertible with him. We got separated, however, when we reached the town as I and another guy decided to stop for a soda while Elvis and two of his buddies drove on to somewhere else.

Well, from what I gathered from Elvis and the others the next day, it all happened when they decided to return to base. In great spirits they had tumbled into the car and gotten into a race with another auto. Elvis had put his foot down on the gas and really drove, until they all heard the sound of sirens.

That meant two Saturdays of driving school for Elvis. Driving school was the regulation base punishment for anyone who had a driving violation, whether on or off duty. And I guess it wasn’t a too good a thing to happen to someone whose actual job it was to drive for the Army.

Anyway, Elvis went along to the school and had his lessons. But I wondered if they’d had any effect, because I remember something red flashing past me at very high speed on the road out of our camp some weeks later—and it looked very much like a Lincoln convertible.

The trouble at the NCO’s club was around the same time. Everyone wanted to get in there and I was fortunate because my rank was a Specialist Four and that entitled me to belong.

But Elvis was still a private. Anyway, one particular Saturday we’d all heard that a band was coming down to play and that Elvis used to sing with them. He was very eager to see the boys in the band and somehow we managed to get the permission for him to get into the club that night. On Saturdays there was usually a dance for the officers and their wives or girlfriends, and each week we hired a different band.

I was already in the club—long before Elvis arrived. I was sitting in the dining room section, just near the door, having a bite to eat with a few buddies. Then suddenly the door swung open and Elvis came in. He was with some other friends and we. all said “Hi” and then they went through into the bar where the band was playing. He told us he was anxious to speak with the boys of the band as it had been a long time since they’d met.

We went on eating. Then about five minutes later we heard some screaming. It didn’t seem like the usual laughing or joking that comes from the bar. We got up and went through to the next room.

Well, I don’t know which one of us was more surprised. It was as though the place had been raided. Chairs and tables were upside down, people were on the floor. The women were yelling and some were even crying.

Someone pushed me to one side. I looked around. It was the head of the club room—and he was hanging onto Elvis’ arm, dragging him out, screaming, “Get out of the way!” I noticed Elvis’ tie had been knocked to one side, that his sleeve was torn, and his usual calm expression had changed to one of fury.

Then someone else tapped me on the arm. I turned around. It was one of Elvis’ buddies.

“What happened?” I yelled, above the noise.

“It’s the girls,” he screamed back. “When they found out Elvis was here they made straight for him, practically tearing off his clothes trying to get his autograph. The manager had to ask him to leave—but he couldn’t get away and in the end they had to escort him out.”

Well, after that, there was only one topic of conversation in the bar that night . . .

I guess, though, in the main, we were all pleased to have him on base. I know it made my last weeks there far more interesting. And as I packed my bags and said goodbye to my buddies, I couldn’t help thinking about Elvis—about how I’d miss all the fun I’d had being at the same camp with him. And as I passed his bright red convertible on the way to collect my own car from the lot, I couldn’t resist stopping to give one of the wheels a friendly kick before driving off for the last time. I kinda missed having him around when I got to my new base.

THE END

—by MARV SCHNUR, formerly of the Second Armored Division

IF YOU HAVEN’T SEEN ELVIS ROCK IN M-G-M’S “JAILHOUSE ROCK” YET, YOU MAY BE LUCKY ENOUGH TO CATCH IT IN YOUR NEIGHBORHOOD.

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE MAY 1959