Marilyn Monroe Enters A Jewish Family

At the end of June, 1956, Marilyn Monroe, in the presence of Arthur Miller and his family, and of Rabbi Robert Goldburg, affirmed her acceptance of these age-old Biblical words. In the article below, takes great pride in presenting the warm and beautiful story of how Marilyn, the orphan girl without roots, has found peace and security in the Faith of the man she loves.

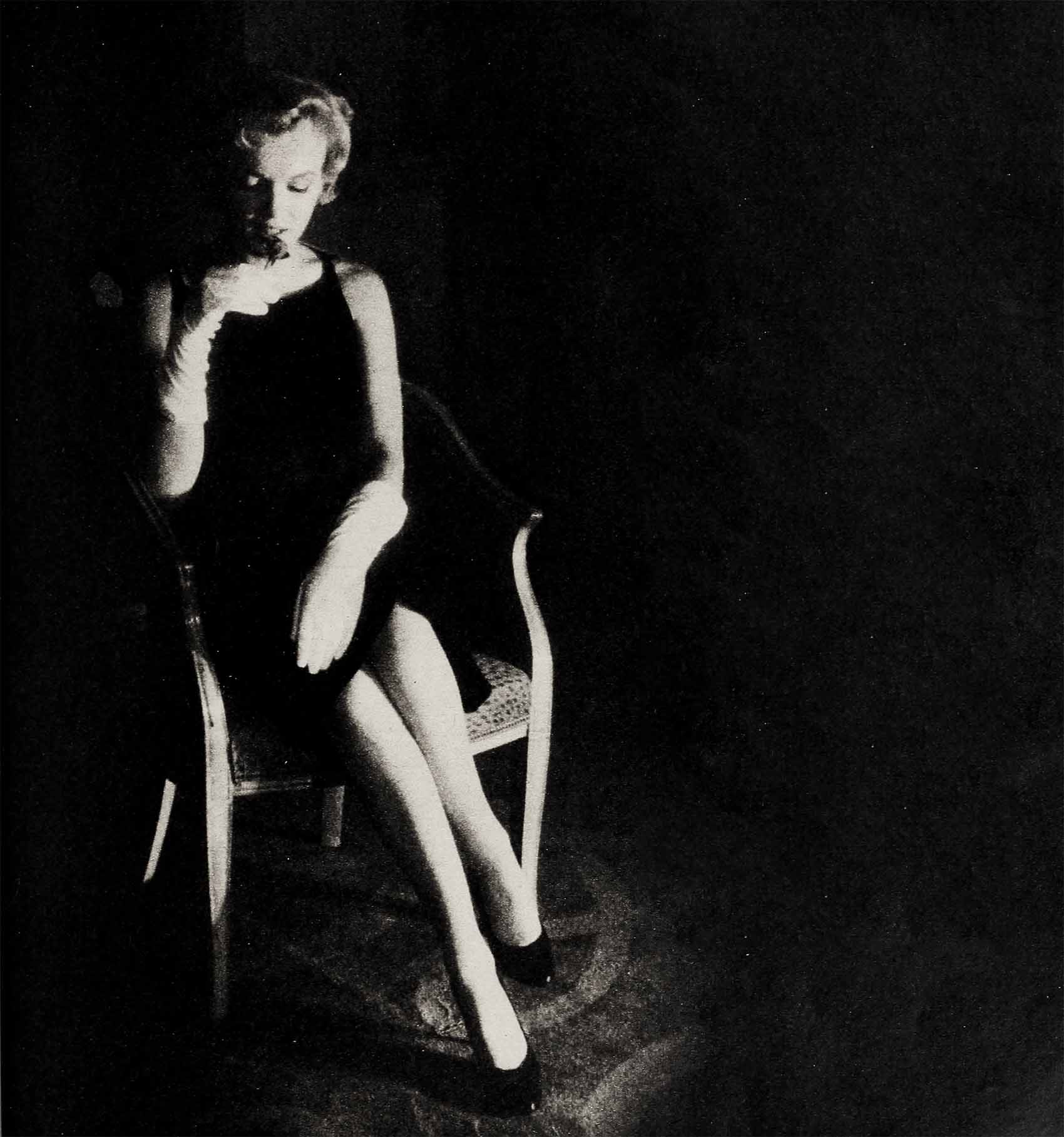

It was a cloudy day, but the little chapel of the synagogue was lit with the soft, subdued, radiance of a pale summer sun filtered through stained glass. Inside, a girl named Marilyn Monroe sat quietly in a center pew, looking down at her white-gloved hands. Her golden hair, brushed back and smoothed, curled out at the ends beneath a tiny veiled hat. Her dress was demure and simple, her face scrubbed beneath the dusting of powder and the light lipstick.

On her left sat her mother-in-law and her father-in-law. From time to time the elder Mrs. Miller raised a hand to pat at her hair. Her husband fingered the prayer book in the rack before him, drawing it out from time to time to turn the pages and linger over old, familiar prayers.

On Marilyn’s right a tall, thin man consulted his watch, glanced at his bride, then reached out a large hand to cover her small one. She turned to him and smiled. There was no fear in her smile, not even a trace of nervousness. It was one of the most important moments of her life, this short time of waiting until the Rabbi would enter and begin the ancient conversion ceremony that would make her a Jew for the rest of her life. As important as the civil ceremony shortly before that had made her Arthur Miller’s wife. On that day she had looked a woman, with a woman’s joy. But today in her eyes was the glow of a little girl, waiting for something very wonderful to happen.

It was, she thought, looking steadily now at the sacred ark in which reposed the holy scrolls of Jewish faith, something for which she had waited all her life.

When she was a little girl, she had no family, she had no home. Her mother was—away. Her father was a man she never knew. Her home was a foundling home sometimes, or else it was a house in which a family lived, and she, the boarder, the ward of charity, stayed. Sometimes they were good to her, sometimes they were not. It didn’t matter much, for they were strangers all.

In the foundling home, she was taught to say prayers. Supposedly she said them to God, but as far as she knew, she said them to the matron who came to listen and look cross if a word were left out. They didn’t make much sense to her anyhow. She asked for blessings and to be good. With or without the prayer, she was good. With or without it, there was no blessing. What did it matter if a word was left out? This God, whoever He was—He was a stranger, too.

In one of the houses where she was put to live for a while there was a man to whom God was no stranger. At least that was what he said. She guessed it must be so, because the man talked about Him all the time. He made her talk about Him, too, and think about Him. All day and all night. It seemed that God made a lot of rules that she hadn’t known about before. Things she must do, and must not do, especially on Sundays. According to the man, in the sight of God she was even less than she had always thought she was—and that was pretty little. She was a sinner, who thought wicked thoughts, and planned wicked deeds. The man didn’t know what they were, and she didn’t know either, but God knew, and He would punish her. If she thought her life was bad now, she should just wait till God caught up to her; then she’d see. Nights she lay trembling beneath the blanket, under the all-seeing, never-sleeping eye of God, waiting to catch her in wickedness.

Time passed, and the authorities in charge of her life took her away from that home and put her into another, and another, and back to the foundling home, and then out again. The memory of the man and his God faded and became a blur of prayer and fear. Sometimes one or another of the families she lived with took her to church, and she heard about God again. Sometimes He was the God of the man, terrifying and awesome. Sometimes he was a gentle God, loving and kind, helping instead of punishing. At first she tried to make sense out of it, but she couldn’t. No one else seemed to have trouble knowing who God was, only she. She asked no one; she was unaccustomed to asking questions. People preferred that she do as she was told and be quiet. She never stayed long enough in one place to go to Sunday School, to meet a minister. In the end, she decided that God was as the rest of the world—a friend to others, a stranger forever to her.

When she was sixteen she married a boy, and thought she was going to have what she had never had—a family of her own, a warmth all round her. But it turned out that he was just a boy, not a father and mother and a whole world. Just a boy, with not too much to give, at that. Or maybe she asked too much of love, having starved for it for so long. Eventually, his was one of the homes she left.

Nine years later her name was Marilyn Monroe, and under that name, she married again. This time she married a man, not a boy. His name was Joe DiMaggio, and as far as Marilyn knew, he was the first person in the world who ever needed her.

Like her, he was lonely. Like her, he was famous, and surrounded by people who offered their time, presence, laughter—but seldom their love. They would open, she thought, as she had thought before, the whole world to each other.

And again, she was wrong. Her new husband was a quiet, moody man to whom real warmth was foreign. Before they were married, he introduced Marilyn to his family, his sister, the San Francisco house in which he had lived. She thought they were to be her relatives, with all the meaning that word had for her. People who would make her part of their world, people she could call daily, have secrets with, defend. But San Francisco is a long way from Hollywood, and Joe preferred to stay home in Los Angeles. He was fond of his family. But he felt no clinging need to know them intimately as Marilyn did. She suffered at the loss.

They were married in a civil ceremony. They could not have a religious one; Joe, a Catholic, had incurred the displeasure of his Church by divorcing his first wife. By marrying Marilyn, he cut himself off from his religion entirely. His new wife’s searching mind looked, as ever, for the answer to her childhood questions. Who is God? How is He worshipped? Cut off from the Church, Joe tried to forget it. He had no answers for her. God to whom she had hoped to find a path, seemed to retreat.

It was a marriage that could not last.

When it was over, she went to New York. She needed to learn to live. A long time ago she had been nobody, and needed only to survive. Then, too quickly, she was Somebody, and she lived as Marilyn Monroe was expected to live—in a way that never touched her soul. Now she would find herself.

For a long time she had been reading. Poets, great novelists, books of philosophy, books on art and music. She had grown accustomed to the laughter and wisecracks that came when she told anyone; she didn’t mind too much. It was good for her career, she supposed. Even if it weren’t, she’d go on reading. Somewhere in the books were the answers she sought.

While she was looking for herself, she found Arthur Miller.

Five years before, she had met him at a Hollywood cocktail party. They had talked for a while—at least, he had talked, and she had listened. What he thought of her she did not know, but to her he was a giant, a man of mind, a man who knew the answers to questions, a man she could worship. But only from afar. She was still the little nobody, hiding behind her publicity, wondering who she was. He could never have been interested in her. And even if by some miracle he had been—he was married. There was an end to it.

Yet, she put a snapshot of him—she never told where she got it—on the wall over her bed, next to the one of Eleanora Duse, the great actress. Everyone recognized the picture of Duse (and laughed at her, of course), but few recognized Arthur Miller in blurred focus. She was content.

When she came to New York to recover from the blow her marriage had been to her, she met him again. He was separated from his wife. And she—she was the unexpectedly bright Miss Monroe, the only person in a roomful who knew what she was talking about when, amid giggles, The Brothers Karamazov was mentioned.

“It’s very strange,” he told her, “that you should be so interested in Dostoevsky. As as a matter of fact, he’s one of my favorites . . .”

Marilyn smiled at him. “Not so strange,” she said. “You told me that back in 1951.”

That wasn’t all she remembered. He was interested in social welfare, so was she. He loved bike-riding—she had always wanted to learn. He liked parties that were more talk than dancing—and at those parties Marilyn turned up, holding a vodka-and-orange-juice, scarcely sipping it, listening, always listening. One evening he drew her away from a group. “You never say anything,” he accused.

Her large eyes turned on him honestly. “I’m afraid,” she said. “There are so many of them, and they know so much . . .”

So he took her away from the crowds and together they discovered who she was—a shy, beautiful girl with a lot to say, when she could find the courage to say it. Time after time she sent him into peals of helpless laughter with a well-timed crack. “Why don’t you talk like that at your press conferences?” he’d gasp.

“Oh, they’d just say my agent wrote it.”

He ale her bike-riding, and when she fell. on the famous behind, she rose up again, giggling. He met her for lunch in Manhattan, and found her hidden behind a scrubbed face and loose blouse, chatting with drugstore waitresses and newsdealers. He came to depend more and more on seeing her, on hearing her comments on his work, getting her opinions of his friends. To her it was incredible. Arthur Miller wanted to see her, to talk to her, actually to listen to her. Gradually a little of her shyness left her. If Arthur Miller thought she was worth while, maybe a few others might, too. For the first time in her life, she felt—liked.

But it was when he took her home that they fell in love.

Home, to Arthur, was a frame house in Flatbush, Brooklyn. Not much of a place to look at he told Marilyn. His mother told her more about it while Marilyn sat on a kitchen chair and watched the busy, capable fingers preparing dinner. Once the Millers had been wealthy, and lived in a lovely place in Manhattan. Then came the Depression. Everything went. They were barely able to manage the move to Flatbush. Arthur was a good boy. Always wanting to help. He delivered bagels before school to earn some money. Bagels—“Here, I’ll show you,” Mrs. Miller exclaimed, producing one from a bag in the oven. A hard, round, roll-like affair with a hole in the middle. Had Marilyn ever had one? With cream cheese and lox?

Marilyn said yes, she had. Lots of her show-business acquaintances were Jewish; she had eaten lox and bagels with them.

Oh, well, then, she knew about Jewish foods and things. Not that the Millers kept a Kosher home, with no pork or rump steak or shrimp allowed in it; not that they didn’t have cream in their coffee when they had it with meat. But still, they were not completely unreligious. For years her old father had lived with them, and for his sake they had kept the dietary laws. It did no one any harm, and in many ways it was good. It reminded them that they were Jews. It was good to know who you were. And being Jewish—well, when people like you were in trouble, or when something good happened, you could share a little of it with them, you could feel at one with them. Did Marilyn understand?

Yes, she understood.

At dinner Mrs. Miller and the quiet man who was Arthur’s father reminisced . . . the time Arthur fell off his bike into the snowdrift and all the bagels got soggy. What a catastrophe—soggy bagels. Never mind the bagels—the catastrophe was Artie had to pay for them! Remember the time Artie couldn’t get into college because his high school grades were so low? The Millers turned, seriously, to Marilyn. You see, they told her, in a Jewish family, the education is the most important thing. More than money or position. To a Jewish family the thought that the son will be a doctor or a lawyer or a teacher or a writer—that is what makes you hang on through bad times, gives you courage to live. So when Artie suddenly wanted to be a writer— well; they were pretty shocked, because he was always the one playing ball or tinkering with a motor, while Kermit, the older one, God bless him (he left after two years of college to help his father when the crash came), was the one they had always thought was artistic. But if Artie wanted to study—more power to him, he should have every penny they could scrape together. So two years after he got out of high school Artie had both the money and the guts at the same time; he went up to Michigan University and talked them into letting him in. Then he won every prize for creative writing they had to give. Proud? Were they proud? They beamed on him all over again. Marilyn, listening, watching as they told her the story, knew that nothing would ever make them as proud again.

Dinner over, they carried the dishes into the kitchen. “Let me help,” Marilyn begged, and Mrs. Miller handed her a towel. Drying the dishes, listening to the chatter, she was supremely content. The arm her hostess put around her when they went back to the living room, the smile Artie’s father turned in her direction when she wandered over to the bookcase to look at the titles,—they all seemed natural, homey, right. “You never wanted to move?” she asked.

“No, we thought of it once or twice. We could afford it now; Artie makes a good living, my husband does all right. But you know—you get close to your neighbors, you see the same people for twenty years, your children grow up in these rooms, you belong to the temple—why should you leave? For a fancier neighborhood with fancy strangers? You understand?”

“Oh, yes,” Marilyn said. She understood.

When they said goodnight finally and walked down the block to Arthur’s car, she held his arm, looking about her. Down the block she could see the outline of a temple. Here and there a porch light gleamed faintly on a mezzuzah nailed to a door jamb—a sign, put up by the residents, that they were Jews, obeying the commandment to keep the word of God nailed to the entrance of their homes that they might remember it always. Inside the mezzuzah, Artie’s mother had said, was a tiny scroll beginning with, “Thou shalt love the Lord . . .”

“It all comes back,” she said slowly, “to being Jewish, doesn’t it?”

Arthur took his pipe out, “All what?”

“Knowing who you are. Being content. Everything.”

He grinned. “Well, a lot of people who aren’t Jewish know who they are and they seem pretty happy.”

“I suppose.” She was silent for a while. “But your family—they say they aren’t religious, really. But still—it’s always there, being Jewish—a sort of constant beauty in the background.”

He looked at her. “Being Jewish is not always a beautiful thing. It can be one of the roughest things in the world. People—”

“I know. But even suffering can be a good thing, if you don’t do it alone, if you share it with people who believe in the same things, who understand . . .” Her voice drifted off into the night. Holding hands, he drove her back to the city.

They never knew who proposed to whom, and finally they gave up trying to figure it out. “Let’s just say we both talked at once,” Arthur said. Marilyn got in the last word on the subject. “You could say it was simultaneous—but I guess he sort of initiated it!” They told that to reporters outside Marilyn’s Sutton Place apartment before Arthur swept her into his car and made a mad dash for his place in the country. With them were his two children and his mother. Waiting for them, his father. Waiting also were a troupe of reporters and cameramen who literally laid seige to the house. Sometimes they braved the storm. More often they stay in, Arthur reading and smoking, Marilyn in the kitchen.

“Teach me to cook,” she begged his mother.

“You can cook. You made a very good steak and a nice salad.”

“Oh, that.” Marilyn waved her hand. “I mean—the kind of things you make. What Arthur likes.”

“Well, I don’t know where to start.”

Marilyn thought. “Gefülte fish?”

“Oh, no. Much too difficult. I tell you what—we’ll try some stuffed cabbage. That looks hard, but it isn’t. And it’s all written down in the Settlement Cook Book, so you can look it up. Get me—”

And Marilyn, delighted, flew about the kitchen, producing failures and successes, most of which were devoured, indiscriminately, by Art’s kids.

Over one such dinner they discussed the wedding. Should they try to elude the reporters—or invite them? Who should witness the ceremony? Who should perform it, a judge or a j. p.? Arthur and his father debated. Marilyn sat silently.

Arthur turned to her. “What do you say, honey?”

She blushed. “I think I’d like to have a Rabbi.”

“A Rabbi? You mean you want a religious wedding?”

“Yes, I thought it would be—nice. I wanted—a blessing on the marriage.”

Arthur was uncomfortable. “Well, I thought of it of course, and the folks would love it—but the thing is—a Rabbi can’t marry us because you aren’t Jewish.” He paused. “Of course, if you were Jewish—”

There was a long pause. Then a voice, “Do you—would they—is there any way I could become a Jew?”

“Well, if you want to, there is.”

“Want to,” she said, “want to! I’ve been wanting to talk to you about it for so long! I thought after we were married. I could—but I didn’t know if anyone could just—become. I thought it was—closed.”

“Closed.” he said, laughing. “Nope, not at all. We have to call a Rabbi, that’s all, and give you instruction. Then there is a ceremony and they ask you questions If you’re sure. You know you don’t have to. Our marriage will be perfectly legal without it, and it doesn’t matter to me. You have to be sure. You have to have thought about it.”

She looked at him. “I haven’t thought about anything else,” she said. “With the possible exception of you.”

They phoned a Rabbi, Dr. Robert Goldburg of New Haven. Yes, he would give the instructions and perform the conversion ceremony. No, no trouble at all.

In her room that night, Marilyn lay awake. Her mother-to-be had kissed her and cried. Her father-to-be had folded her in his arms. The warmth around her was to be hers, not by right only of marriage, but by right of faith. Whatever was to come, she would share with them, and they with her. Never had she felt so much that she was coming home.

The next day tragedy struck. They went for a drive, briefly. On the way home a reporter followed them, driving wildly to catch up to the car far ahead. Looking out the window as Arthur’s car climbed the winding road, Marilyn saw the car below crash and spin. They got help and went home. “It’s got to stop,” Marilyn said.

“How do we stop it?”

She sighed. “Give them what they want. Get married.”

They made arrangements quickly for a brief civil ceremony. When it was over, Arthur took her aside. “Honey, you know we are married now, even in the eyes of my religion. If you don’t want to go through with the conversion, you don’t have to.”

“I want to be a Jew,” she said, “as soon as possible. I want it now, before we go to England. I want to be married again, in temple. This doesn’t change anything. I only want it more.”

The Rabbi came to the house. All that day and all that evening he told Marilyn what it meant to be a Jew. Her husband was a “Reform” Jew, so she needn’t keep Kosher, nor sit apart from him at services, as she would if they were Orthodox. She would light candles on Friday night to welcome the Sabbath, which lasted until sundown Saturday, but need not refrain from touching money or riding on that day. She would be, he told her, as Jewish as she wanted to be. He gave her the Old Testament to read. At the end of the evening, he took Arthur aside. Usually, he said, the conversion ceremony followed a much longer period of instruction. He knew there was no time for that, since they were due to leave for England. He understood Mrs. Miller’s desire to be married again in the religious ceremony. She could return for more instruction when they came back. He would make an exception—the conversion would take place the next day and the second marriage promptly thereafter.

Arthur came back to Marilyn, who was waiting anxiously. “You’ll do,” he said.

And so, on that pale morning, Marilyn sat in the chapel, remembering.

A door opened and the Rabbi came in.

“Marilyn,” he said gently.

She rose and stood before him. Quietly the service began.

“Is it of your own free will that you seek admittance into the Jewish fold?”

“Yes.”

“Do you renounce your former faith?”

She had had none; she renounced her lack of faith. “Yes.”

“Do you pledge your loyalty to Judaism? Do you promise to cast in your lot with the people of Israel amid all circumstances?”

It is good, she remembered, to suffer—if you share it with others. . . . “Yes.”

“Do you promise to lead a Jewish life?”

She thought of her new family, holding each other close in a bond of love. “Yes.”

“Should you be blessed with children do you agree to rear your children according to the Jewish faith?”

Her children, who would forever know who they were, who would have an answer to their questions. “Oh, yes,” she said.

The Rabbi smiled at her. “Repeat after me” he said, and together they spoke the ancient words of the convert:

“I do herewith declare in the presence of God and the witnesses here assembled that I . . . seek the fellowship of Israel.

“I believe that God is one, Almighty, Allwise, Most Holy. . . .

“I believe that man is created in the image of God; that it is his duty to imitate the holiness of God . . . that he is destined to everlasting life. . . .”

And then one of the oldest prayers the world has ever known.

“Hear O Israel: the Lord our God, the Lord is One.

“Praised be His name whose glorious kingdom is forever and ever.”

Marilyn’s voice stopped. The Rabbi said, “Thou shalt. love the Lord thy God with all thy heart and with all thy soul and with all thy might. And these words which I command thee this day, shall be upon thy heart. Thou shalt teach them diligently unto thy children, and shalt speak of them when thou sittest in thy house, when thou walkest by the way, when thou liest down and when thou risest up. . . .”

He read her the words of Ruth. Behind her she could hear the rustle as her family rose in their places and began to read aloud, “Let us adore the ever-living God and render praise unto Him who spread out the heavens and established the earth. . . .” They were praying—praying for her!

The Rabbi took her hand and gave her solemnly a name chosen from the Bible—a name she keeps entirely to herself. “With this name as token you are now a member of the household of Israel and have assumed all its rights, privileges and responsibilities.” His hand was on her head. “May He from whom all come, send His light and truth to guide you.

“May the Lord bless thee and keep thee;

“May the Lord let His face shine upon thee and be gracious unto thee;

“May the Lord lift up His countenance upon thee and give thee peace. Amen.”

It had been a long road, a hard road. But with shining eyes and a blessing upon her, Marilyn had come home.

THE END

—BY SUSAN WENDER

The editors of MODERN SCREEN are grateful to the Union of American Hebrew Congregations (parent body of the Western Hemisphere’s 534 Reform Temples), and to its director of press information, Rabbi Samuel M. Silver, for the assistance given to us in preparing this story.

Marilyn is in the 20th-Fox film Bus Stop.

It is a quote. MODERN SCREEN MAGAZINE NOVEMBER 1956