The Kid From Philly—Eddie Fisher

Studio 6 B at WNBT-TV was humming.

Outside the door, an usher had a list of those who were to be permitted inside during the rehearsal. It was a long list. In the TV theatre the audience seats were occupied by an assortment of producers, writers, kibitzers, TV technicians, press agents, song-pluggers, fans and friends. They were all there to see Eddie Fisher or to attend to business connected with some offshoot of his career.

The person who seemed least affected by the activity and excitement was Eddie Fisher himself, the star of Coke Time.

Because of his vivid coloring, his black curly hair, deep brown eyes and tanned skin, the tall TV star is better looking in person than he is on the television screen. He moved effortlessly among these people, stopping to say “hello” to a friend, to confer momentarily with his manager or to step onstage and rehearse a number with Ann Crowley, the pretty singing guest of that day.

Eddie had a word of greeting, a smile, a nod for everybody. Virile, vibrant and personable, he seemed to be exactly what a young American star should be.

Since he got out of the Army last April, after a two-year hitch, ex-private Edwin Jack Fisher’s rise to fame has been meteoric. While he was in G.I. garb and maybe on some Army detail, entertaining in the front lines at Korea or another U.S. base, or recruiting on the home front, his singing voice rang out on radio and juke boxes around the country. Some $300,000 in record royalties from his long string of song hits was piled up and waiting for him on his return to civilian life.

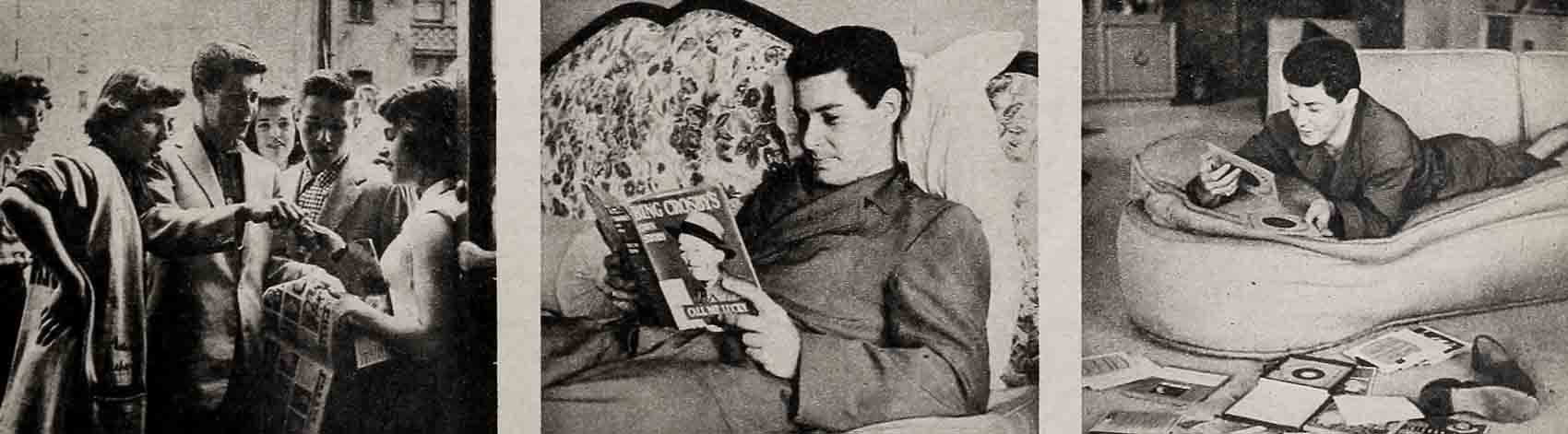

Eddie Fisher alighted in New York from a Washington train one morning last April, and still in uniform, went directly to the Paramount Theatre. His fans were lined up, impatient to see their singing hero.

Backstage, a tailor and a hurriedly-hired valet were waiting for him in his Paramount dressingroom. His clothes for the opening had been ordered long distance. Cashmere sports jackets, slacks, blue suits and two tuxedoes, all fresh from the tailor’s workroom, were hanging neatly on the racks. The transformation from Private Fisher, soldier, to Citizen Fisher, singer, was completed.

An hour or so later, onstage at the Paramount where Frank Sinatra rocketed into fame via bobby-soxers’ swooning, Eddie Fisher was crowned the new “King of Sing.” To make his coronation official, the first week after his Army discharge, he launched his twice-weekly TV and radio show, Coke Time.

Lest he have time to catch his breath, the bachelor baritone temporarily suspended his American activities to take his place in the spotlight of the London Palladium where Britishers flocked to see and hear the slender singer. He was making a benefit appearance at the Red, White and Blue ball, a big charity affair at the Dorchester Hotel, when he received a note from a young lady in the audience.

“Don’t be nervous,” it read, “the response may not be like that at the Palladium, but I shall lead the applause and they will love you.” As everybody knows by now, Princess Margaret Rose, sister of the Queen of England, was Eddie’s royal cheerleader. After he sang, she invited him to her table.

This acclaim abroad and his popularity at home might turn another’s head, but not Eddie Fisher’s. He’s grateful for it.

He lives unobtrusively in a 4½-room, furnished apartment on New York’s Sutton Place, which he took over lock, stock, furnishings and books from Eddie Cantor. He got his headlong start to success four years ago, when the older Eddie heard the younger Eddie sing at Grossinger’s, a Catskill Mountain hotel, and hired him for a cross-country personal appearance tour.

A hospitable host, the singer welcomed MODERN SCREEN into his home. In the diningroom, an alcove off the livingroom, a round pedestal table was attractively set for luncheon. One whole wall consisted of windows opening on a view of the East River with its bridges and barges.

The singer’s personal belongings were strewn with wifeless abandon around the room. In one corner on the floor, there was a big movie projector and photographic equipment. Against one wall was a piano, and piled atop bookcases and a combination TV set and phonograph, were stacks of long-playing records, classical and modern.

On the lower shelf of an end table were mementoes of Eddie’s trip to London, “Golden Book Of The Coronation,” “The Connoisseur, Coronation Book, 1953” and “King George V, His Life And Reign.”

There was evidence of the life and reign of King Eddie Fisher, royal crooner, too. He has a plaque in crest form, imprinted “Eddie Fisher, London Palladium, Variety Season, 1953.” A glass-encased gold record of RCA VICTOR’S “Anytime” was shining testimony that his recording of that song had passed the million-sales mark. In a corner cupboard was a trophy, a sculptured figure holding a gold disc and inscribed, “The Cash Box, in behalf of the Automatic Music Industry of America, the Best Male Vocalist of 1952.”

There were no personal pictures around the apartment, no likenesses of pretty blondes or brunettes.

In his bedroom, besides the unmade bed were well-stocked closets and dresser drawers. Hanging alongside his expensive suits was a khaki souvenir of his Army days, his G.I. jacket with the Korean and Overseas medals still fastened on the front.

“I like to keep it where I can see it. It reminds me how lucky I am,” civilian Fisher said.

Being able to buy all the clothes he wants is a comparatively new experience for him and he doesn’t pretend not to enjoy it. Cashmere jackets, shirts and sweaters are his sartorial weakness, he admitted. Black is his favorite color in suits. Not funeral black, but the shining richness of mohair cloth or shantung.

“Somebody gave me a black cashmere sports shirt,” he explained, “and I just liked the color.” Argyle socks, colored handkerchiefs (which he wears in his jacket pocket in preference to white), sweaters and sports shirts were tossed about in the drawers. It looked as though the owner had dressed in haste.

“I have a valet, but he’s away on vacation and I’m kind of lost without him.” His one other servant, Gypsy, an attractive, poised maid, prepared luncheon.

“Bring some melted butter for the lobster, will you please, Gypsy?” he re quested, gnawing unglamorously on an ear of corn. True to his sponsor, he drank several Coca-Colas.

When Eddie excused himself to answer the telephone, Gypsy discussed her famous boss.

“He only has dinner home on Tuesday and Thursday nights,” she said, “and I never know how many there’ll be for dinner. He often calls up an hour before and says he’s bringing several friends home to dinner.”

During luncheon, relaxed and easy to be with, Eddie talked.

He had celebrated his twenty-fifth birthday on August 10.

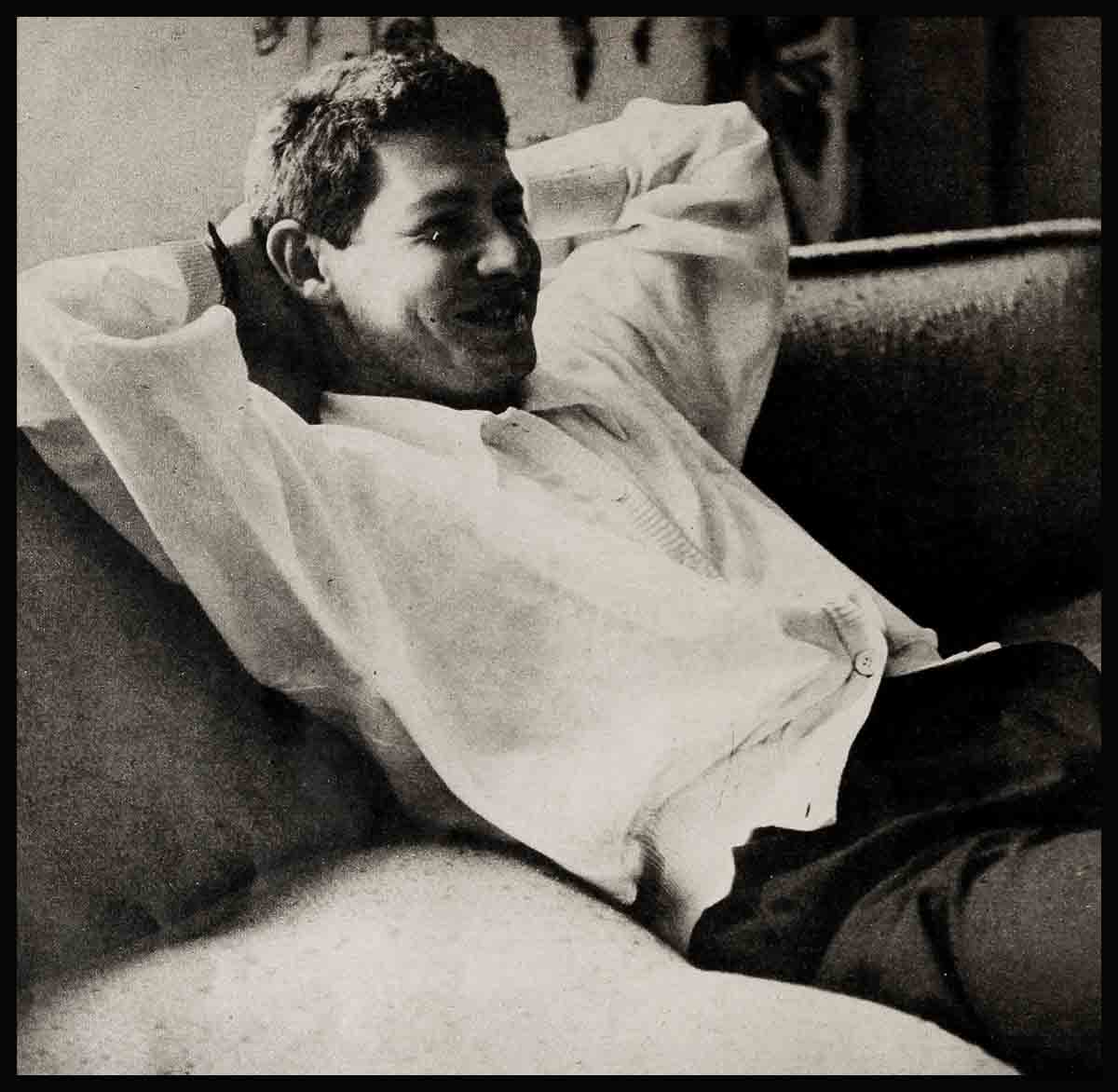

A DAY IN EDDIE FISHER’S LIFE IS FILLED WITH FRIENDLY PEOPLE, WORK AND CASUAL LIVING.

“I think back when I came to New York eight years ago and it seems like yesterday,” he said. “I think I should be about eighteen now and I’m twenty-five. Otherwise, I feel very young. I’m ready to go . . . I’m kept busy these days, but I was just as busy in the Army. I always had to be up early. I used to record at 9 A.M. for the Army shows. At least I don’t have to do that now.

“I sing best when I feel good, when I’m not under pressure and when I sing what I like. When I was in the Army, I didn’t always sing what I liked, but when you’re in the Army you do a lot of things you don’t want to do.”

His face and voice are very expressive as he speaks, although he says he was bashful and shy as a kid. The fourth of Kate and Joe Fisher’s seven children, he had a tough life as a youngster in Philadelphia. The Fishers didn’t have much money, and Eddie used to accompany his father’s fruit and vegetable wagon, vending his wares in song.

He has sung ever since he can remember, in the synagogue, in amateur contests, over radio station WFIL in Philadelphia. His mother nicknamed him “Sonny,” because as a little boy he used to imitate Al Jolson’s “Sonny Boy.”

When he was seventeen, he came to New York to seek fame and fortune—and a singing job.

“I went down to the Copa and auditioned for Monte Proser,” he recalled. “I sang many songs. Afterwards, Proser told me, ‘I’ll pay you $125 a week. Is that enough?’ I would have paid him to let me work there if I had had the money, but I didn’t realize I’d be singing with girls. I wanted to sing alone and I wanted to sing what I liked. That’s why I didn’t want to sing with the bands.

“I woke up wearing a costume and singing with eight girls,” he said. “I was at the Copa for three months. It was like home. Joe E. Lewis was the star while I was there. I sang songs like ‘The Great Big World Is Yours And Mine,’ ‘Simon Bolivar’ and ‘They Say That I’m Too Young To Know’—and they’re so right,” he ad libbed. “I was and I still am.”

A special evening at the Copa is a bright spot in Eddie’s memory.

“They would have informal evenings,” he said, “when Joe E. Lewis would introduce the celebrities in the audience. One night Frank Sinatra, Eddy Duchin and Vic Damone were there. Vic had just started to work at the Martinique. Joe E. Lewis introduced all of these people. Then he said, ‘Now I got a kid. This is my kid.’ And he pointed to me! I felt like crying. I went on after all these people and sang. Afterwards, a couple of people wanted to be my manager, but Milton Blackstone, a friend of Monte Proser’s and head of an advertising agency, became my manager.

“Everyone said to him, ‘What are you messing around with this kid for? He’s not good enough. He’s not going to be that big.’ But Blackstone was one of the few people who really had faith in me. He has taught me many things. He taught me patience, which I didn’t have.”

Eddie needed patience. After his thirteen-week stint at the Copa he was out of work for nearly a year, with an occasional singing engagement at some small club, or the steadier but financially not very remunerative work of singing on the staff of Grossinger’s.

As he sat on one of the modern sectional couches in the livingroom, looking casual and comfortable in brown slacks, a white, long-sleeved sports shirt and brown and white loafers, the TV star discussed many things: that he likes to get presents; he doesn’t smoke, although once in a while he’ll pick up a cigarette, but doesn’t inhale; that when he first came to New York he saw a Perry Como picture. He couldn’t remember the title but he remembered that Perry sang “Here Comes Heaven Again.”

When he played in a recent golf tournament, he was in the foursome behind Perry Como.

Eddie sang his own song hit which was particularly apropos, “I’m Walking Behind You.”

Perry’s answer was his favorite quip, “You crazy, mixed-up. kid,” and then Perry burst into song, kidding back, “Mine, Tell Me That You’re Mine.”

Eddie’s buddy, Bernie Rich, dropped by. Bernie has his own apartment, but while his mother or visiting friends use his abode, he bunks at Eddie’s.

This is very convenient for Bernie. He gets to wear Eddie’s shirts, socks, and ties which as he says, “are so much nicer than the ones I can afford.”

Bernie can have delusions of grandeur, too, for Eddie lets him drive his new navy blue Cadillac convertible. They’re used to sharing what they’ve got because for a long time they had nothing between them.

Five years ago, Bernie and another friend from Philadelphia, Joey Forman, came to New York. Bernie wanted to be an actor and Joey a comedian. Eddie was living in a hotel room and his two pals moved in. Since Eddie was the only one working he got the bed. Joey used to take the mattress off the bed and sleep on the floor. Bernie didn’t have it so good. Frequently he found himself relegated to the bath tub.

Bernie had one phrase to describe his friend Eddie: “Completely selfless.” “There’s nothing he wouldn’t do for any of his friends,” he said, and told how when Eddie was booked into the Paramount after being discharged from the Army, he insisted that Joey Forman be signed as the comic for the stage show.

Excusing himself with, “You don’t mind if I borrow one of your shirts, do you, pal?” Bernie left.

Eddie called after him, “See you at rehearsal. Do you want to borrow the car?”

“No, I’ll let you use it this afternoon,” Bernie said generously.

Laughing after him, it was evident that the comfortable-as-an-old-shoe friendship he enjoyed with Bernie helped to relieve the strain and tension of many a day. As long as Bernie and Joey Forman were around it was pretty hard to think of himself as anything but Eddie Fisher, the poor kid from Philadelphia who used to play “Slick” on a teen-age program there for 15¢ a week carfare.

“Ever since I was a kid, or ever since I can remember, show business was a big dream,” Eddie reminisced, “show people and people like Bing Crosby, John Garfield and Al Jolson weren’t like other people to me. They. weren’t earth men. But when I came to New York this whole bubble burst. It wasn’t what I thought it was. It’s glamorous but not as glamorous as I thought it would be. There’s only one thing left—the movies. I was out there in 1949 and I had a taste of it.

There was a chance he might go to Hollywood, the TV star said. His agent was talking over a one-picture-a-year deal with Paramount.

“If I made a picture I’d like to play opposite Debbie Reynolds,” he said, “but I don’t suppose Paramount could borrow her.”

It was the first time in all his conversation that Eddie had mentioned a girl. Except for an occasional line in a column, linking him with a pretty model or an aspiring actress or a young singer, there have been no stories about his romantic life. But there have been theories and speculation.

“He’s carrying a torch for a girl he was in love with,” some said.

“The truth is,” whispered others, “and I have this right from the horse’s mouth, that he has been told not to get married for fear he’ll lose his bobbysox following.”

“Nah, that’s not the reason. He won’t marry anybody unless his mother approves of her.”

If a fellow won’t talk about his girls, other people will, especially if he’s famous, for when a man becomes successful there are all sorts of people who knew him when, the “I remember” friends.

“Eddie went with a girl by the name of Joan Wynne,” a Fisher expert had told MODERN SCREEN a few days before the meeting with Eddie.

“He met her when he sang at the Copa. She’s in the chorus at the Riviera now. Nobody knows why they broke up.”

Joan Wynne was sixteen, brown-haired and blue-eyed, when she first met Eddie Fisher at the Copa. She’s twenty-four now, and still single, as cute, pretty and shapely as ever, but her hair is tinted a soft red and she wears it short in the current fashion. Backstage in the dressingroom of the Riviera nightclub, where she has worked for three seasons, she was willing to discuss Eddie.

“Eddie and I were a big romance for a long time,” Joan Wynne admitted, “something like five years. When we first met we were both just out of high school, a first job and everything. There wasn’t any of this glamour or anything there is now. It was completely different.

“Besides working in a, nightclub, we never saw the inside of one. In the first place, Eddie never had any money. He only worked at the Copa for three months. I was there for a year and a half. After he left, he didn’t have a job for almost a year, I’d say, but he still came around to the Copa and waited for me. He never came into the club because he didn’t have the money. He didn’t like to be around like a bum.

“When he was working at the Copa, we used to go for walks along Fifth Avenue and Central Park between shows. In the afternoons, we went to the movies on Forty-second. Street, sometimes two and three double features a day. Eddie loves the movies. Afterwards, we’d have a hot dog. That’s all we could afford.

“Sometimes we visited his family in Philadelphia. We talked about a lot of things, our future, religion. His career was always uppermost in his mind. It came first, which is the way it should be, I suppose.

“We used to have a lot of fights and arguments, then two years ago at Christmas we had a big fight. That was the beginning of the end. He wrote to me when he was in the Army, and we’re still friends. A couple of weeks ago, he was out at the Club with some friends. I went out and sat down with him.

“I don’t think he’s changed at all. He has good instincts. He isn’t flighty or fickle. It’s just that there are always millions of people around him, a million phone calls, a million things to be done. It’s as though he hasn’t had time to rest. He thinks nothing of working hard and singing and meeting people.

“Eddie always said I was the only one he could ever really relax with, but after we had our big argument, I started seeing other people. I want to be happily married. I met someone who is just about the finest person I ever met. He’s wonderful, but Eddie was on my mind when I met this person and I know that was bad.”

Why, then, if this love of Eddie’s had consumed a fifth of his lifetime, was he so reluctant to talk about it? Or maybe there was some truth to the report that Eddie’s mentors thought it better if he remained single.

These were questions that only Eddie could answer.

He was there for the answering, relaxed and handsome, sitting in his livingroom, one of the most successful entertainers in America, today, and an eligible bachelor.

Because he is a nice person—honest and anxious to be liked and understood he broke his long silence about his love life, his romantic interests and told his side of the story.

His dark eyes flashing, he unleashed his feelings.

“I have never been advised by my managers nor anyone else about my personal life,” he said adamantly. “I’m free to do whatever I want, when I want, and how I want.

“It’s just that I have been so tied up with my career, with the TV show and radio, that I haven’t had time for much social life. This is the first time since I’ve come back from the Army that I’ve been in one place so long.

“As for Joan Wynne, she’s a wonderful girl. We’re friends. We went together for a long time. I was just starting out in show business. I didn’t meet many people. We always went around together. I was struggling and she was very, very nice. We were good company. I went steady with her, but I was out of town a lot. I never knew anybody when I came to town. I’d call her up and we’d go to a movie, sometimes two or three,” he chuckled.

“Although we went together for a long while, I guess I just didn’t love her enough, if I didn’t marry her. All my time was spent with my work, with my singing. There was never a girl in my life who came before singing.

“This business of not getting married because it might affect my career is nonsense. I won’t get married until the right girl comes along.

“I like the outdoor type, the natural girl. I would prefer that she not be in show business. It wouldn’t be good to have two careers. There’d be a conflict. I’m very jealous. I would want my wife all for myself.

“So far,” he said simply, “I haven’t met the right girl. When she comes along, it’ll be wonderful.”

With fervor and feeling, the bachelor baritone had cleared up the secrecy surrounding his love life. He proved another thing, too—that he’s an all right guy looking for the right girl.

THE END

—BY JOAN KING FLYNN

It is a quote. MODERN SCREEN MAGAZINE NOVEMBER 1953