Kirk Douglas’s Island Of Safety

Two years ago, on a warm sunny afternoon in Paris, Kirk Douglas was introduced to a petite French woman, who his friend director Anatole Litvak said, was just as brilliant as she was charming. She spoke four languages fluently, had an indefatigable supply of energy, a quick, sharp mind and a fine sense of humor. She was just the person Kirk needed to handle his French papers while in Paris making “Act of Love.” When Anne Buydens agreed to take care of the actor’s work, the director arranged the meeting that afternoon.

“There was no romance involved,” Kirk says today. “Not in the beginning. Anne helped me with my business problems. She was stimulating, gay, soothing. Having worked on pictures with picture people, she knew about actors. From the beginning, we had a perfectly good understanding of each other’s good points and bad ones and an acceptance of each other’s qualities. I appreciated having her as a friend.”

Anne lived and worked in Paris where she coordinated languages in foreign films—on pictures shot in France or in Italy with English-speaking actors—and arranged and coordinated the Cannes Film Festival. Kirk left France soon after “Act of Love” was completed and did not see her until a year later, in Rome, where he was locationing in “Ulysses.” Anne, by some good fortune, was working as language coordinator on the film, too.

“We got together and soon began seeing each other as frequently as possible all during the filming,” says Kirk. “But afterward, when I left to return to Hollywood I had no plans for the future—although I did know how much Anne meant to me.

“All I knew was that I wasn’t going back to Hollywood—not to live. I’ll commute, between Paris and Hollywood, Rome and Hollywood, perhaps New York and Hollywood, but never, for me again, life in Hollywood.

“Never is, of course, a ridiculous word. For I did come back, and to one of the most moving experiences in my life.” For in Las Vegas, Nevada, on May 29, 1954, Kirk Douglas married Belgian-born Anne Buydens and in so doing landed on what he describes as “The Island of Safety I’ve been trying to find all my life.”

For the four years prior to this marriage, Kirk had been, by his own admission, in kind of a bad way. Not careerwise, as his recent pictures “Act of Love,” “Ulysses,” “20,000 Leagues Under the Sea,” “Man Without a Star,” “The Racer” can attest.

The trouble was within himself.

Previously married to actress Diana Dill and the father of two sons, Michael, ten, Joel, seven, Kirk and Diana were divorced in 1950. And after the divorce came the restless life, for Kirk, of the rolling stone, homeless, often lonely. “Sometimes on the mad merry-go-round that is even worse,” he says, “than loneliness.” He was confused. The confusion was of a man who has lost his way.

“I was in a constant state of flux between elation and depression,” Kirk today describes his past troubled state of mind.

“My confusion began,” Kirk admits, “right after I made ‘The Champion.’ I was very depressed, yet I couldn’t think why. In this picture I was; and I quote, ‘catapulted to stardom.’ Thanks to producer Stanley Kramer, who gave me the opportunity to play that atomic role.

“The point is that I had made a number of pictures, six in all, before I made ‘The Champion.’ I had worked like a man possessed in each and every one of them and although I got good notices in all of them, and particularly in ‘The Strange Love of Martha Ivers,’ my first film which starred Barbara Stanwyck, I wasn’t a star. No one really noticed me until after I made ‘The Champion.’ After ‘The Champion’ everyone noticed me and with a suddenness like the sharp upgrade of a roller-coaster. Everyone said I’d ‘changed.’ The intimation, on one hand, being that the change was for the better; on the other hand, quite the opposite. I hadn’t changed. I haven’t changed now. Except I’m seven years older.

“Being told I’d changed was a contributing factor in my state of confusion but not enough, of course, to account for my depression. After all, people were talking about me, weren’t they? Writing about me. The spotlight was on me. What more does the ham in every actor crave? More flatteringly (and remuneratively), scripts were coming in. Fan mail coming in. Contracts offered (‘Write your own ticket’), photographers and reporters training their lenses and pens on me. The ‘full treatment.’

“All my life I’d dreamed of this, of becoming an actor, a successful actor, and here it was, come true. But in attaining the dream, I had lost the dream.

“How? When? Where? Most of all, why? I asked myself. I probed the questions. I did a lot of self-analysis and I finally came to the conclusion that nothing in life is as fabulous as you dream it. This is a truth we should all anticipate and for which we should all be prepared. I hadn’t anticipated it. I wasn’t prepared to face it. I didn’t face it. This was my trouble.

“My dream of becoming an actor had been an adolescent dream, a romantic dream of playing exciting roles to thunderous applause, my name in lights; a rags-to-riches dream of dwelling in marble halls.” For a fraction of a moment Kirk’s lips tightened, then he went on, “A Hollywood hacienda with all the trimmings. I had not visualized the hard work that must be done, the mad race that must be run before this halcyon state of affairs can come to pass; if, indeed, it ever does, or can.

“I had run that race in the beginning, every day a mad race to get a job, a part in a show, a part on radio, one radio show to another—a race, literally, to get something to eat. In-between shows, any job I could get (part-time work at Schrafft’s Restaurant, anything), in order to eat.

“I was used to working, you know, it wasn’t that. As a kid, in my home town of Amsterdam, New York, a constant shortage of cash in the family till and a minimum of food in the icebox made me a wage earner while I was still in grade school. At five every morning I rose to deliver papers before school and raced from my last class of the day to deliver the evening papers. I used to count myself lucky if I was through my labors by seven o’clock. After graduating from high school I spent the following year working in Amsterdam department store in order to earn money for college. At the end of the year I took my savings, totalling $163, and hitch-hiked to St. Lawrence University in Canton, New York. The final stage of my journey still amuses me—I arrived atop a truck filled with fertilizer! Thanks to a part-time job as a waiter I managed to graduate with an A.B. degree and with a record as undefeated intercollegiate wrestling champion for a period of three hard-fought years—which stood me in good stead when, later, I barnstormed with a carnival as an exhibition grunt-and-groaner.”

(Stood him in good stead as the muscular and mighty Champion, too.)

“Yep,” Kirk said, “I was used to working and, although I was the only boy in a family of six girls, I was not used to any coddling and spoiling. No time in our family for anything softer than,” he grinned, “hard work.

“But poor boys dream tall dreams—taller dreams than luckier boys. They dream of rags-to-riches. My dream was of becoming an actor, a successful actor which, when accomplished, would mean that the race was run, the struggle over.

“When it wasn’t over, when even after I’d made ‘The Champion’ I was still running to find stories, material, still fighting, still breathless, I was confused—this, because I wasn’t facing it, was the real cause of my confusion.

“I used to work at one period of my life in a steel mill. When I’d get through an exhausting day in the studios, tough scenes, things going wrong, I’d really feel beat—much more so than I’d ever felt at the end of a day in the steel mill. ‘What price this dream, this lazy, luxurious dream, of becoming an actor?’ I constantly asked myself.

“All this,” Kirk said, “may be interpreted as a complaint. It isn’t. It is an attempt at honest evaluation. And to be honest, much of my exhaustion was my own doing, my own fault. For my big problem was that for so long I had had to fight for everything I got, from enough to eat to a college education, from ‘playing the part’ of an off-stage echo in the Broadway production of ‘Three Sisters’ to the starring role in ‘The Champion,’ that I went into every scene I played, fighting. Attacked every scene I played like a lion on the kill. When offers began coming at me without any aggressive action on my part, offers of parts and contracts, I wasn’t geared for this sort of thing. I expected to fight. That no one expected me to fight, this was confusion.

“When I read my own publicity, some very good indeed (too good for me), now and then not so good, I reacted accordingly—a word of criticism and the dukes were up; a flattering word and a kitten’s purr.

“Childish? You said it.

“In every actor there is, and there must be, a childlike quality. This I’m sure of. Look at me, a grownup playing,” Kirk laughed, “Ned Land, the harpooner in ‘20,000 Leagues under the Sea.’ If I didn’t have the childlike quality, I couldn’t do it. Not without embarrassment, at any rate, and not believably.

“No man is completely a man who has lost out of himself all of the boy. Or, if he does, he becomes a very dull human being. It is also true if I begin to believe I am Ned Land or The Juggler, or Dempsey Rae the roving cowhand in ‘Man without a Star,’ this would be sheer madness.

“In the same way an actor should not believe all the good things written about him, or all the bad. Just as he is not really any role he plays, whether heel or hero, so he is not either heel or hero in real life. In other words an actor should not react, as the child in him is prone to do, by extremes, as I did, between elation and depression.

“One neurosis I did escape, however, and that is the fear, common to the actor who has achieved ‘sudden stardom,’ that I might fall from the pedestal. I hadn’t this fear because ground and grained in me is the theory that nothing lasts forever, that everything is a cycle, so now as then, I accept the fact that my success will not last (as my poverty did not last) forever.

“I also believe that if you have the opportunity to compete, you should not complain if you lose.

“As an actor, it’s a wonderful thing to be in a position to play exciting roles, on screens all over the world. In Israel, where we made ‘The Juggler,’ kids ran up and said they’d seen me in ‘The Bad and the Beautiful’—it was a thrill, as it was in Rome, being stopped on the street by people who told me they’d seen me in “The Juggler. This part of the dream comes very true. But as picture follows picture and the sense of excitement mounts, the sense of running accelerates, too. As one is achieving one goal he’s already out, still breathless, to make the next goal, until . . . you begin to wonder what goal? and why?

“I think it’s very true in this business that everyone runs so fast and for so long they forget what they’re running for.

“I did.

“When you are cut adrift from your personal life,” Kirk feels, “the confusion increases. To be accustomed all your life to home life, family, routine, then suddenly, to be in outer space and alone, you feel naked, vulnerable, lost.

“I did.

“After Di and I were divorced I felt a stranger to myself, and in my own land. Strangers never feel comfortable. Have no base. Can’t relax.

“On the loose, eh?’ a few old goats would say, goatishly, poking me in the ribs, ‘Playboy, eh? How lucky can you get!’

“But playboys are born, I’m convinced, not made. Nothing in the tough dog-eat-dog life I’ve lived, as boy and man, conditioned me for the playboy role. Nor anything in the close family life I’d lived as a child and, later, as a husband and father.

“As for being ‘lucky,’ you look around at every so-called playboy dating all the glamour gals and they are either unhappy or something is wrong with them. Something damned serious is wrong with them. For the playboy routine is a mad merry-go-round from which you never get off and on which there is no time to develop a real lasting relationship.

“I know about the mad merry-go-round. I was on it and I had it. Even while on it I knew that for all the flaws there may be in marriage, there is no institution to replace it.

“In this business more than in any other, a man needs marriage. An actor, who is exposed to so much, needs marriage more than another man; needs the island of safety only to be found in a solid human relationship.

“I need it,” Kirk says.

“Without it I was a miserable guy. When I was in Europe, making ‘Act of Love’ and ‘Ulysses,’ I was a less miserable guy. The more leisurely pace of Europe made me realize that to be a success in the movies is a much tougher job than anyone realizes, and that there is more than one kind of success. Over there I had a chance to evaluate myself. I was less tired and had more time to be sort of objective.

“In Europe, looking around me, I thought, I’m not going back to Hollywood, never to live. Ever since I’d been living alone, lonely and restless, my friends had been saying, ‘Trouble with you, you’ve been a rolling stone so long, too long for your own good. What you need is a base.’

“I then returned from Europe to a base, to the little one-story house my friends bought for me through Sam Norton, my lawyer, while I was abroad. Fanny Brice’s daughter, Frances, did the decorating. All my friends got together, Sam and his wife, the Billy Wilders, the Ray Starkes, and furnished it—down to the last detail of food in the deep-freeze and toothpaste in the bathroom.

“ ‘If you don’t like it when you walk in,’ my friends said, ‘you can walk right out again!’

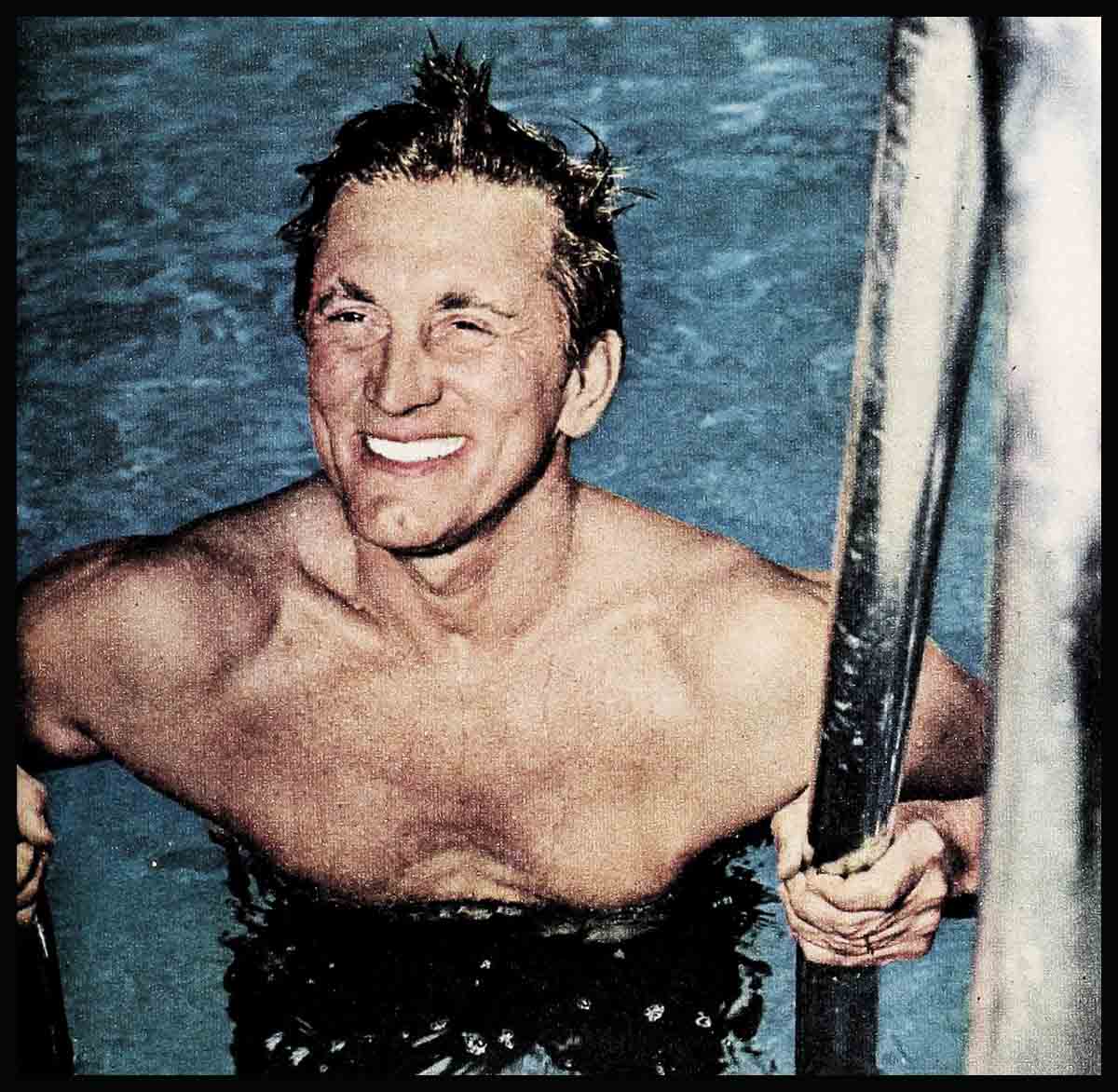

“I liked it. I loved the way it was decorated, all striking black and white. Liked the big comfortable lounges and chairs. The garden. The little swimming pool. More than liking, I was deeply touched. I didn’t know they cared. Not like this. Not to the extent of taking all this time and thought and trouble.

“I was happy to have a place of my own. I’ve bought a few paintings. Many books. I read a lot. People came over and found me mowing the lawn. Friends came over for dinner and I cooked for them—barbecues mostly. I’m a terrible cook, but I insist upon doing it.

“I thought about marrying again and I invited Anne to Hollywood for a visit. I knew even before she got here that she would never go back—not to stay. We both knew. There wasn’t much need of words. The question had been asked, and the answer given long ago.

“We were married and I,” Kirk laughed, “am not running anymore. I used to be like the fellow who ran through the countryside so fast he never saw the flowers or the streams. I see them now.

“In my relationship to people I used to be like a steamship ploughing through an ocean, friends had to cling to you like barnacles. I don’t want to be that kind of a steamship. I’m not any longer.

“I’m through fighting. I’m no longer the lion going in for the kill. When preparing for a picture, I do all the research I ever did, and more. But now I create, or try to; I don’t fight.

“I’m calmer about my career, although I’m as interested in it as I ever was. But I no longer think of it as the be-all and end-all. There’s less desperation.

“I don’t want to always just act. I want to direct; want to be on the Broadway stage again; hope for new fields, for growth.

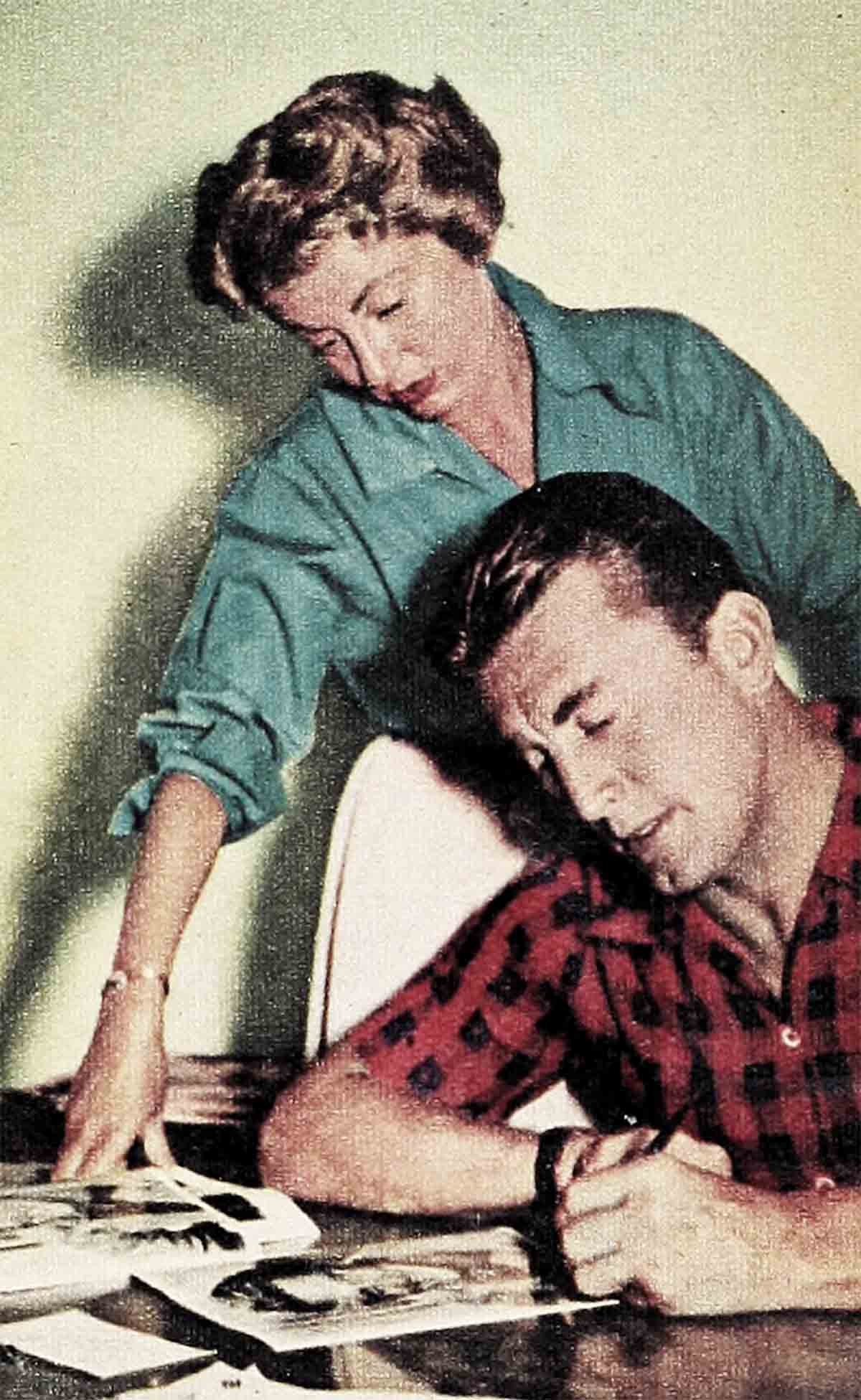

“And Anne, my wife, is interested in my career. She helps me in many ways. Recently, for instance, a German book was submitted to me as a picture possibility. I don’t read German. Anne does. She read the book, told me the story. She knows about my work. But she is not trying to spur me on in my career. She is more interested in me as a human being than as an actor; more interested in my peace of mind, in me. We are both interested in growing together!

“For the present we plan to live here, in this house that was going to be,” Kirk grinned, “my little bachelor haven. At least until we know what’s ahead, whether I am going to do another picture in Europe, or where and for how long. Eventually we plan to build—when, where, as yet, we have no idea. Actually, it doesn’t matter—when you live on an Island of Safety. . . . I did say, ‘Nothing in life is as fabulous as you dream it’ didn’t I? Well I have one correction. The exception, said bridegroom Douglas, is a happy marriage.”

THE END

—BY ELIZABETH BALL

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE FEBRUARY 1955

No Comments