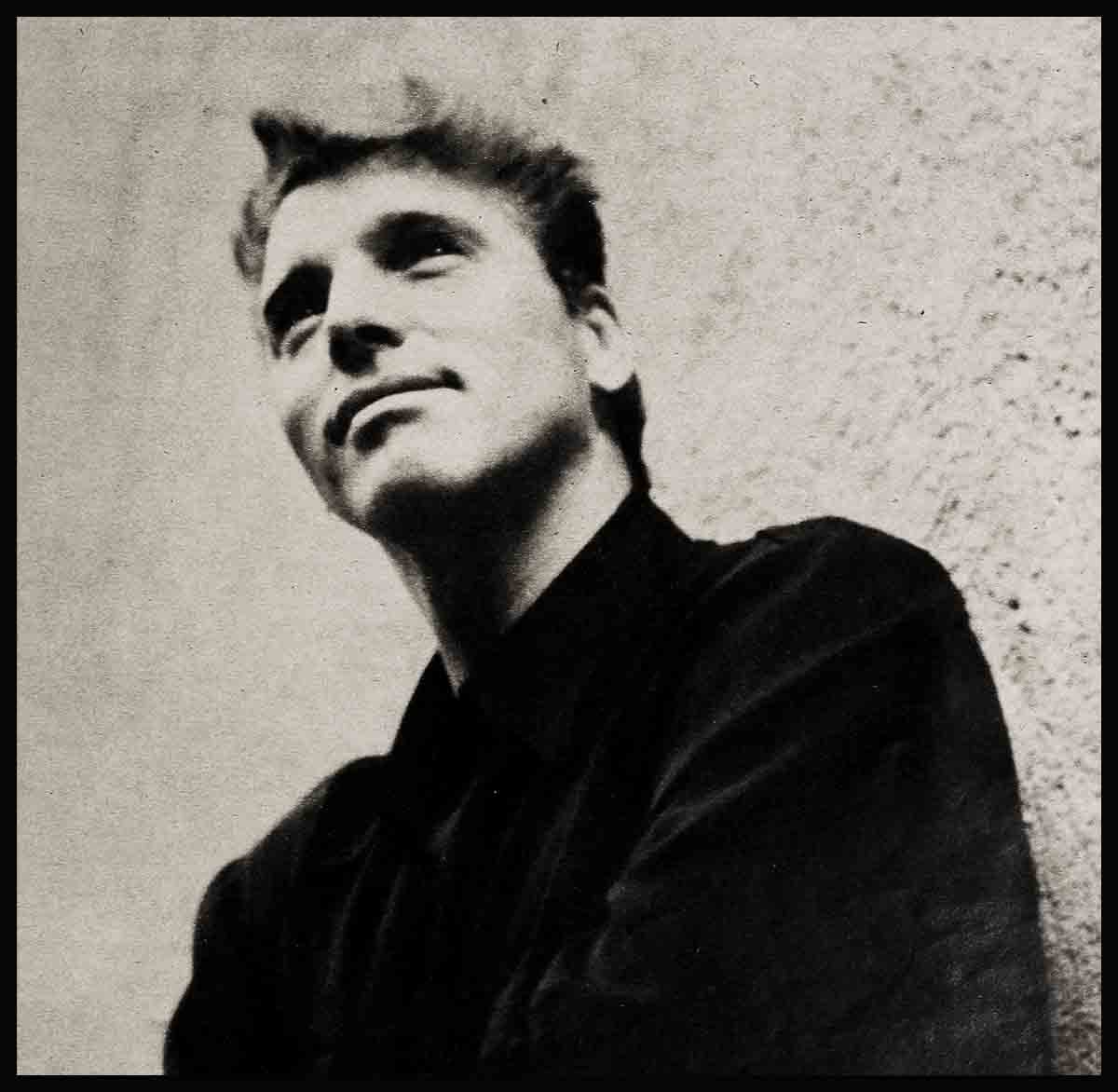

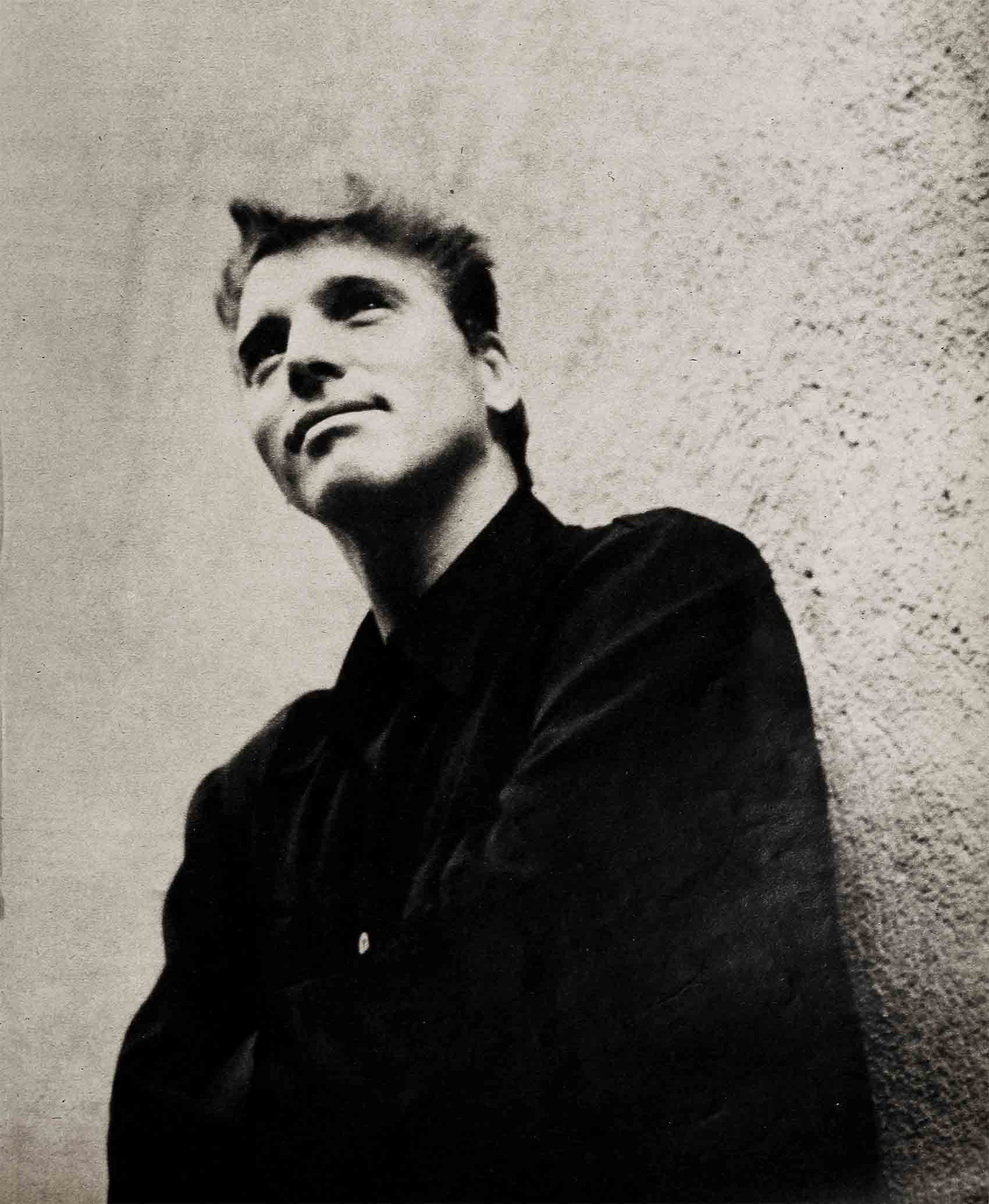

The Moving Story Of Burt Lancaster’s Fight Against Fear Act Of Love!

Seven years ago when Burt Lancaster was relatively new and fresh in Hollywood, he was invited to a dinner party. This festive affair was well-sprinkled with colorful Hollywood characters. A loquacious writer began to spout on half a dozen different subjects.

Lancaster controlled himself for half an hour, but as the writer talked Burt’s face became rosy. Finally he could stand it no longer.

He walked up to the writer, eyes flashing. “You,” he snarled, “are the biggest, no-good, four-flushing phony I’ve ever heard.” With that he whirled and strode from the room.

The writer was aghast. For a moment he stopped gushing like a severed artery. When he could speak above this outrage, he raised a shoulder, pursed his lips and bristled. “Well!” he exclaimed. “All I can say is, ‘Well!’ ”

Not long after that, Burt was starred in a prison film out at Universal. During the course of the production, he turned to an actor and said, “That’s not the way to play that scene.”

“Look,” said the actor. “You mind your business and I’ll mind mine.”

It is by such incidents that Burt Lancaster has made a reputation as a rude, opinionated, stubborn actor. Actually, he has always been honest if not tactful.

Hal Wallis, who gave Burt his first movie contract, likes to tell the story of his first meeting with Lancaster.

“We were in New York,” Wallis recalls, “and as we were walking down Broadway together, he stopped me and pointed to a theatre marquee. ‘Have you seen that picture?’ he asked. I nodded and confessed that I had not only seen it, I had produced it.

“It didn’t stop Burt.

“ ‘That picture,’ he said, ‘really stinks.’ ”

Today when Lancaster recalls such performances he grins sheepishly.

“I’m not like that any more,” he says. And he isn’t. “I’ve learned that a man can be honest without being hurtfully blunt. It’s not important to be well-liked. But it is important for a man to be at peace with himself. A man with inner security does not go around hurting people.”

To show how much Lancaster has improved, note his relationship with fan magazines. Burt used to have no patience with fan magazine writers.

In fact, he gave orders that he wouldn’t be bothered by a coterie of frustrated reporters who insisted upon prying into the most personal recesses of his private life and the lives of his family.

That was the Lancaster of old. Just before he left for Mexico to make Vera Cruz with Gary Cooper, Burt called his publicity man.

“Look,” he said, “a bunch of magazine writers have been after me for months. I’ve been too busy to see them. Why don’t we have them all in for food and drinks—one mass interview?”

The publicity man was delighted.

“That’s great!” he exclaimed. “Only I want you to know they’re going to ask some real dillies.”

“Let ’em ask away,” Lancaster said. “I’m waiting.”

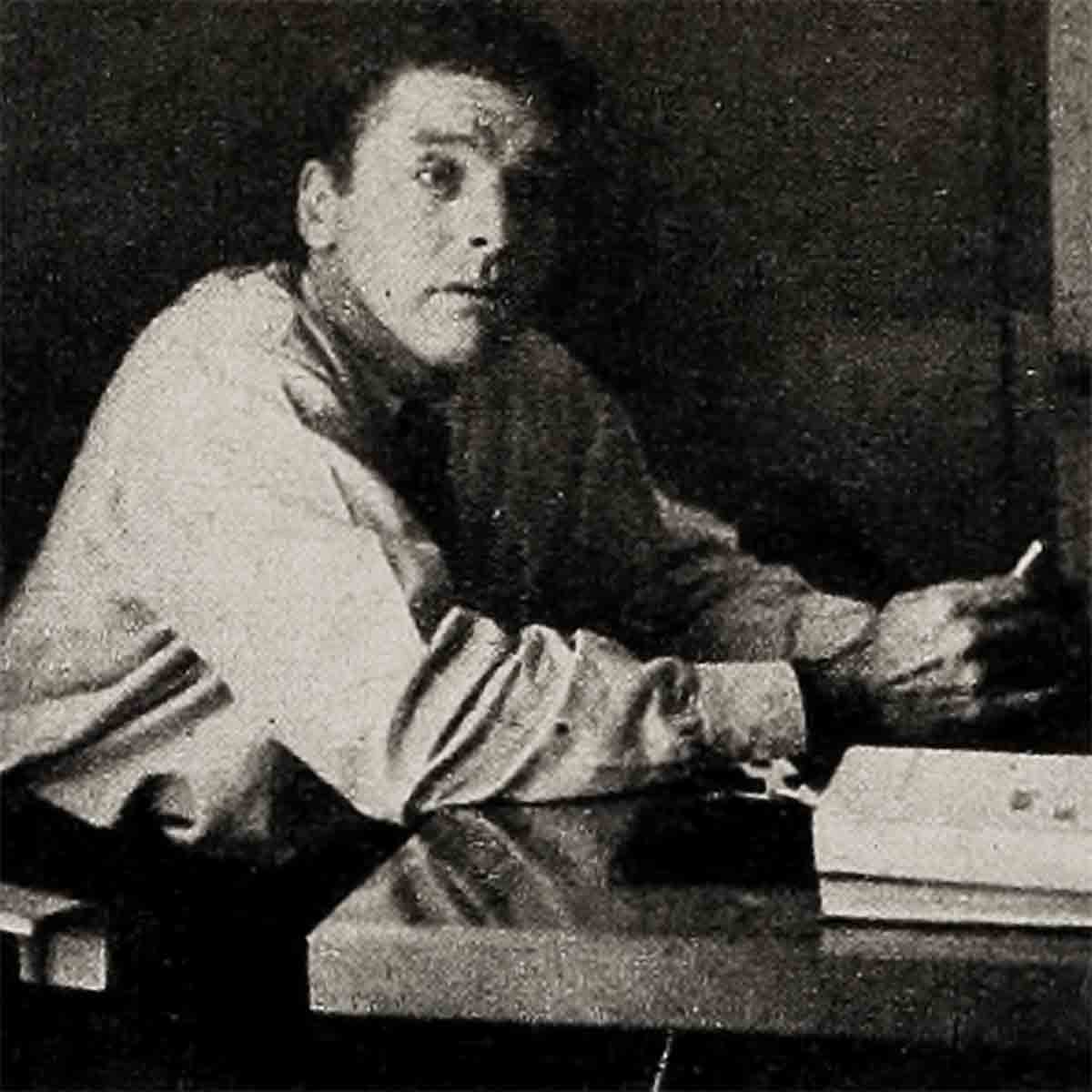

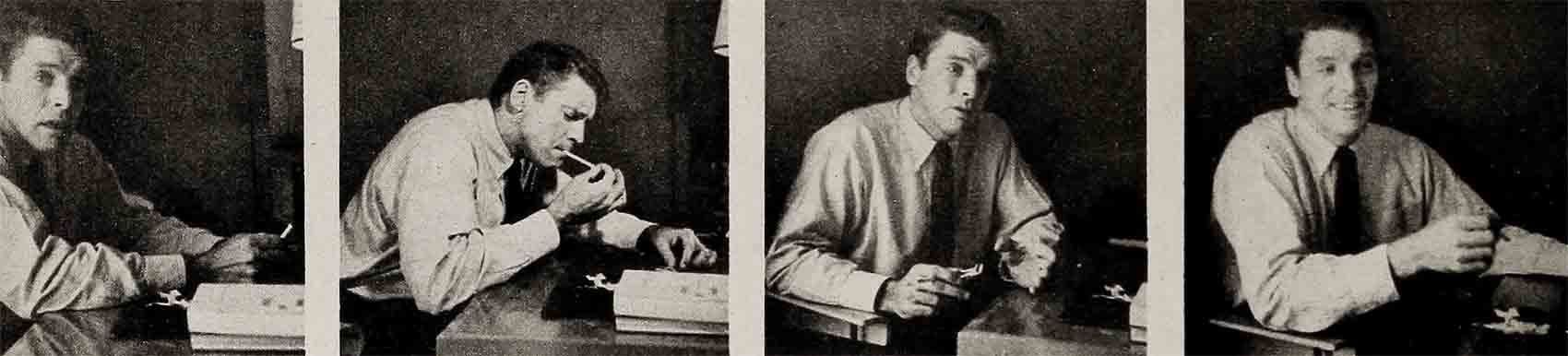

Burt, surprisingly at ease, met them in his new office on the Key West Studio. Here are some of the questions they popped and the answers Lancaster popped back.

Q: And how is the new little Lancaster feeling?

A: Well, that’s a tough one. the child isn’t due until June.

Q: I suppose you like having children, don’t you?

A: My wife does.

Q: Is it true that you do a lot of work around the kitchen?

A: Not any more than I can help. But I do like to cook.

Q: Do you have any passion?

A: I beg your pardon?

Q: I mean do you have any strange passions? Do you ever buy a dozen shirts just for the thrill of buying them?

A: No.

Q: Where are your wife and children?

A: Right now they’re in Mexico.

Q: Are your four children going to school down there?

A: They’re enrolled in the American School in Mexico City.

Q: Why do you keep working so hard? Haven’t you made twenty pictures in six years?

A: I don’t consider it hard work. A man must stay busy. You just can’t be idle. At least I can’t.

Q: Is it true that you drive your children to school each day?

A: Not every day. When I can, I do.

Q: What do you think of your last two pictures, His Majesty O’Keefe and Bronco Apache?

A: I think you’ll like them.

Q: Do you think you’re handsome? Is that why you became an actor?

A: I became an actor because it’s something I always wanted to be. I’ve been in carnivals, circuses, on the stage. I’ve been in show business a long time.

Q: Do you get along with your wife? Do you quarrel frequently?

A: Norma and I get along pretty well.

Q: But aren’t you difficult to live with?

A: I don’t think so.

Q: But you have the reputation of being difficult.

A: I’ve learned and Ive changed. At least I believe I have.

Q: Are you very wealthy?

A: I’m not starving.

Q: How much money did you save last year?

A: I honestly don’t know. You’d have to ask the accountant. How about knocking off and having a little food?

After the interview, the writers said that never before had Burt Lancaster been so cooperative.

“Imagine!” squealed one. “An actor buying food for the press. It’s hard to believe, isn’t it?” Whereupon one cynic suggested the possibility that Lancaster’s reformation was diplomatic expediency brought on by the fact that he now has his own producing company which has a twelve-million-dollar release deal with United Artists.

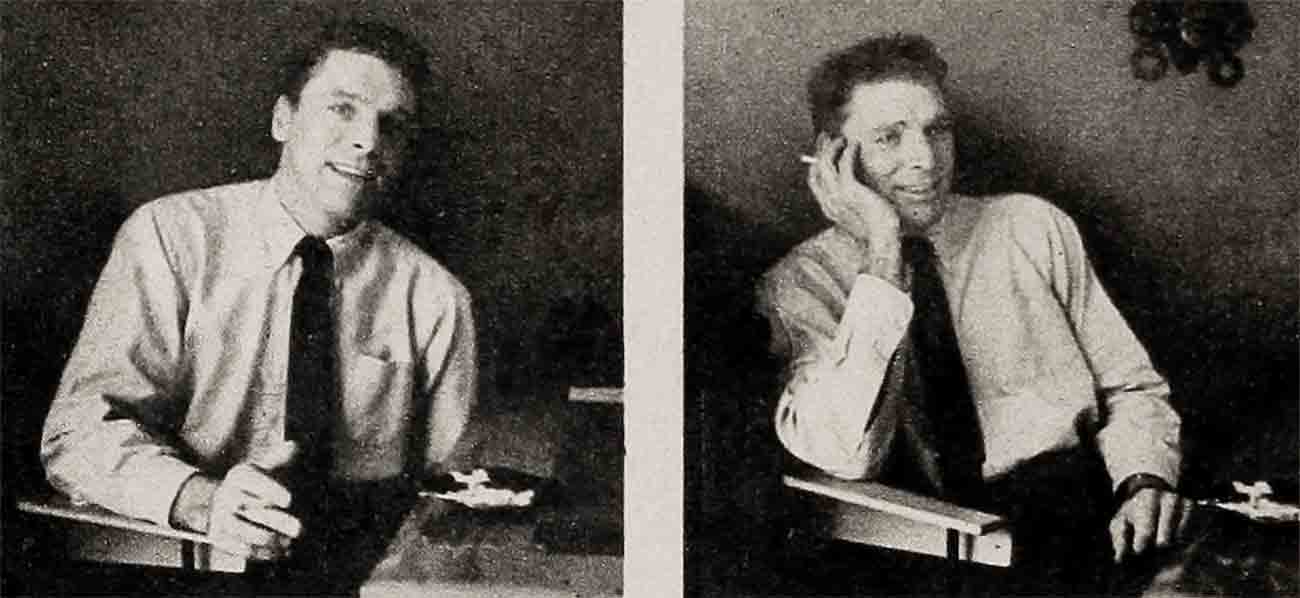

Lancaster’s new behavior, however, is no attempt to protect his production investment. It’s simply that for the first time in his adult life, Burt is genuinely happy.

“I always wanted to be an actor,” he explains, “and to act in good pictures, to get parts with guts and dimension.

“I worked in Come Back, Little Sheba and From Here To Eternity and Bronco Apache. All good pictures. So I’m sort of fulfilled.

“Of course when I first came out to Hollywood, I was scared. Scared stiff. And I did a lot of things and said a lot of things that rubbed people the wrong way.

“I guess I was compensating for my insecurity.”

Lancaster doesn’t like to talk about it, but he was insecure about more things than his career. His marriage, his background and his children. There is no understanding Lancaster or the many facets of his nature unless you have some inkling of his background, of his youth, of his wife, and of his family. He is a moody, complex, enigmatic young man who only recently decided to abandon his rebellion.

Burt Lancaster was brought up in New York City, on the periphery of Harlem. In order to keep him out of the streets, his mother used to have him play on the fire escape of the tenement in which the family lived.

One time Burt fell two stories and broke his nose. He remembers “the eight times I was run over when I started playing in the streets and the library on 110th Street where I did most of my reading as a kid and the movies I used to go to on Saturday mornings. I used to stay all day until one of my older brothers came and got me and after that, Mother used to beat the hell out of me. Then she’d compensate by taking me in her arms.”

Lancaster’s childhood was the youth of poverty. And one of the results of poverty is that it turns young men bitter and ambitious at the same time. Somehow Burt managed to retain his individualism, a stubborn individualism which eventually brought him to swordspoints with almost everyone he met.

A friend who was at New York University with him says he made himself unpopular with his professors. “He quit college, you know, and took a job with a circus for three dollars a week and board. All of us expected him to break his neck but look at him today! Burt has a way of fooling people.

“He’s not as foolhardy and reckless as he leads people to believe.”

One of the shrewdest cookies Lancaster fooled was the late Mark Hellinger, a producer at Universal-International. When Hellinger was making Brute Force with Burt, someone asked, “How’s Lancaster doing?”

Hellinger shook his head. “This kid,” he muttered, “has made one picture out here, and already he knows more than anyone on the lot.

“Two more pictures and he’ll land flat on his can. He’s a frustrated Freudian, a body in search of a brain, Mr. Know-It-All from the Big Town.”

What Hellinger could not understand about Lancaster was his strange individualism. Burt has his own ideas about everything and he believes in trial-and-error.

When he was under contract to Hal Wallis, he became convinced that Wallis was a purely commercial producer; so he borrowed enough money to buy up his own acting contract. He went to work at U-I in All My Sons. It laid an egg. Then he starred in a melodramatic saga of smuggled penicillin entitled Kiss The Blood Off My Hands. The picture almost kissed him off for good. But Burt is resilient. He bounced right back again.

He was the same way in the Army, a renegade from convention. And the Army, as most people know, is not quite the place to exercise individualism. But by exercising it, Burt got married; and this is probably the best move he has made in his entire thirty-nine years.

Some biographies, inaccurate and imaginative, have described Lancaster’s wife, Norma Anderson, as “the former actress, dancer and singer.”

The truth is that Norma Anderson was a stenographer in disguise when Burt first met her. She was disguised as a dancer with a USO troupe in Italy. Norma had worked at a typewriter in the USO booking office in New York. She was talked into substituting for a sick member of a USO dancing troupe and she went on the overseas trip for a lark.

In Montecatini where Pfc. Lancaster was stationed in 1944, she caught sight of her future husband shuffling along a dirt road and asked a surprised colonel to get her a date with him. Burt doesn’t like to talk about how he and Norma fell in love. But the whole affair is melodramatic. Tall, handsome enlisted man meets tall, beautiful blonde. The next morning the enlisted man runs to the USO bivouac.

“I’m sorry,” he’s told. “The whole troupe flew north to Caserta.” The enlisted man goes AWOL. He must find his love. The M.P.’s must find him. Lancaster makes it to Caserta and finds Norma. They have thirty precious minutes together when the M.P.’s arrive and take Lancaster back to Montecatini.

This time Norma goes AWOL. She goes back to Montecatini, and the lovers escape to Pisa where they get married. But the M.P.’s are not far behind.

The honeymoon lasts three days. Then the lovers are caught and Norma is returned to her USO troupe. Her husband is bounced into the jug. Norma is returned to New York City where she works as a stenographer. Burt is returned to his Special Services unit.

Burt landed in New York on Labor Day. Not long after, a baby was on the way. In his own mind he didn’t know what to do or where to turn.

He thought of becoming a manager for a concert bureau, but a producer ran into him in an office building elevator and offered him a job in a Broadway play, The Sound Of Hunting. In desperation he took it.

The play was a flop, but Hal Wallis thought Burt showed a good deal of potential and gave him a Hollywood contract. Mark Hellinger borrowed Lancaster for The Killers when Warner Brothers asked too much on a loanout for Wayne Morris.

It was then that rumors of Burt’s rude behavior began to spread through the movie colony. What the movie colony did not realize was that Burt was scared, heartsick, and perennially worried.

His oldest son Jimmy, now eight, had just been born with a foot deviation. Every two weeks, Jimmy would have his plaster of Paris casts broken, and new ones put on. This went on for eight months. At night Jimmy would scream with fear thinking that the doctors were trying to get to his feet beneath the covers. Norma and Burt would rush into the little boy’s room. Seeing his frantic little face break out in a sweat, each time their hearts would break and they would die a little. Slowly Jimmy withdrew from the unpleasant world of reality into a more comfortable and private world of make-believe.

Jimmy began to feel that he was different because he couldn’t play as other children did. He used to hide and when company came, he retreated to a corner of the room and said nothing. The child’s unhappiness ate deeply into Burt. He heard his son called names. He could see the boy’s initiative being stifled.

Finally he took the child to a psychologist. On an intelligence test, he made a score of 142—which puts him in the potential genius class. The boy was enrolled in a private school where the teachers specialize in caring for emotionally disturbed children. It took time, but today Jimmy Lancaster is a well-adjusted child.

Bright, good-looking, sociable and musically adept, he is one of the most promising young students in the American School at Mexico City.

The Lancasters’ second child, Billy, now five, was stricken by polio when he was three.

When Burt took his family to Italy where he was making The Crimson Pirate, a doctor told the Lancasters that they were oversolicitous about Billy.

“When he falls, let him pick himself up,” the doctor said. “In that way the leg muscles will get stronger. He will be able to throw away the crutches.”

It takes strength and determination to watch your child try to pull himself to the curb after he has fallen in the street—and not to help him. But Burt and Norma knew they had to let Billy fend for himself.

They cried as they watched him. But Billy finally made it. No crutches today, no brace. And in a year or so, the doctors say he will no longer show any trace of paralysis.

Susan Elizabeth—the family calls her Susiebet—has had no trouble. But Joanna, now two and a half, was born with a foot deviation. This time the doctors advised that the feet be let alone, and they have since straightened themselves.

The fifth child is expected late in June, and the Lancasters are praying for a normal delivery and a healthy baby.

In the last five years, Lancaster’s medical bills have averaged $10,000 a year. But strangely enough, Burt has gradually become happier and made a better adjustment.

He has reached the point of believing! in the importance of all human and personal relationships. He has seen what a smile and a story at bedtime means to a child. He knows how much a word of encouragement from a doctor means to him and what a little reassurance does for his wife.

Because of this recognition he has adopted a new set of values. Actors who work with him swear by Burt. He gives youngsters a chance. He lets veterans experiment with their own bits of business —acting nomenclature for technique. He is kind, patient, and understanding.

He no longer fights with directors and writers. He is kind to reporters.

In the Lancaster household there is pervasive love born of suffering and mutual sacrifice and a wordless, nameless togetherness that only Norma and Burt can truly understand.

Burt Lancaster, delivered from the tortures of his soul, is a man of love. In strange, unfathomable ways, love turns darkness into light, fury into peace and anger into kindness.

As an artist and as a man Burt Lancaster has grown and is growing with his children.

THE END

—BY ALICE HOFFMAN

It is a quote. MODERN SCREEN MAGAZINE MAY 1954

No Comments