How Pursued My Husband—By Mrs. Gene Nelson

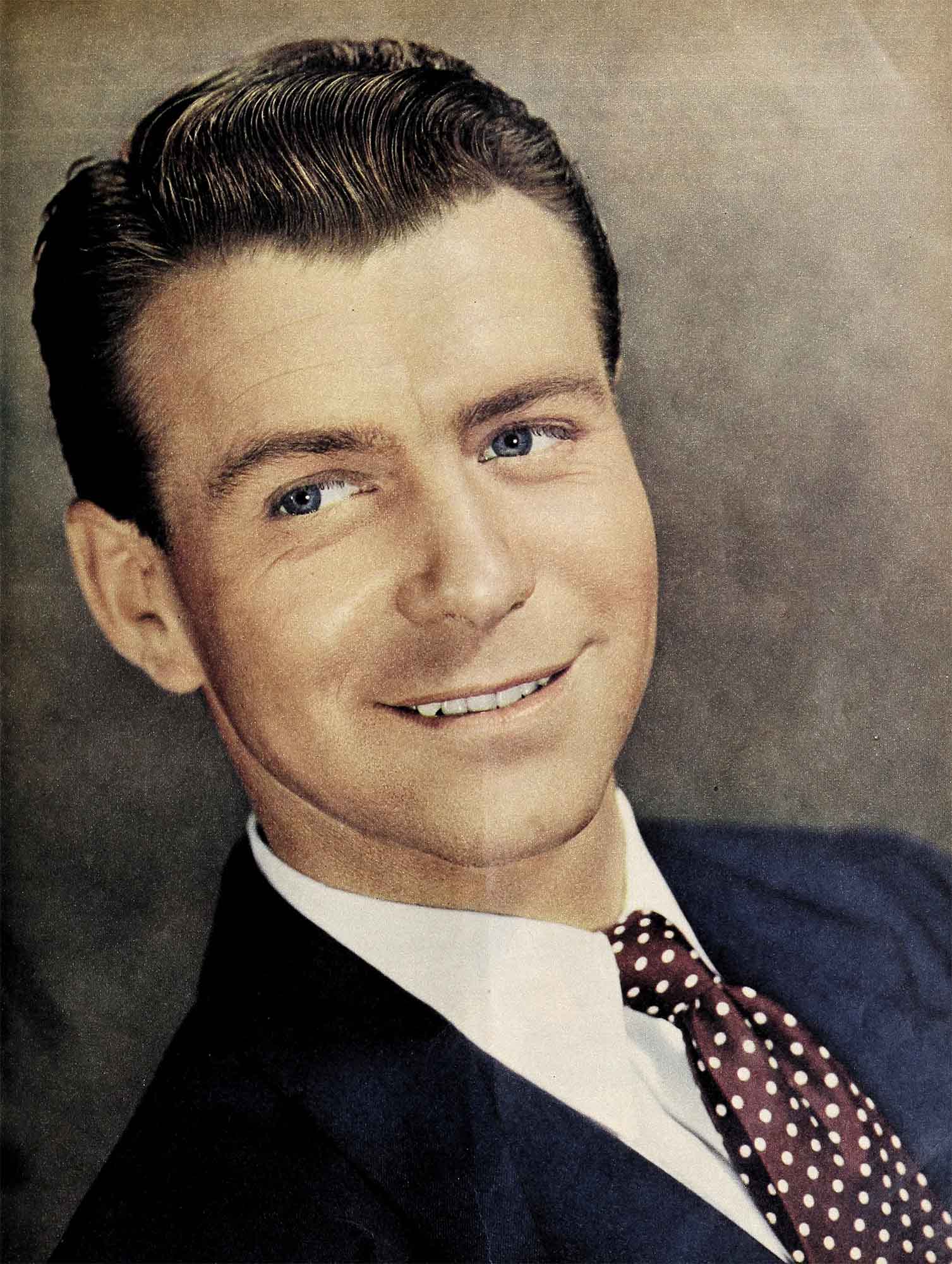

The first time I saw Gene, I flirted with him. I was feeling quite elegant and gay, wearing my new red fox fur jacket and sitting in the fourth row at the New York Center Theater ice show. Gene skated gracefully across the arena. He was tali and blond and handsome, a whirling figure in blue. As he stood poised to go into a spin, he glanced up, our eyes met and we both smiled. The rest of the show he played to me. He would take one bow to the audience, another to me. It was a frank flirtation, teasing and meaningless. But I must, I decided, see him again.

I made mental lists of people who might know him and tried to sound casual when I asked other dancers in “Panama Hattie” if they knew Gene Berg—his real name. Finally, I hit the jackpot.

The wardrobe lady for Gene’s show, May Kelly, had “dressed” me for three shows. So the first night I had off from “Panama Hattie’’ I went to the Center Theater again. Backstage, before the curtain, I told May Kelly why I was there. She suggested I come back later.

A darling and a diplomat, May knew that I wanted only to meet Gene. But deliberately and casually, she introduced me first to others in the cast. Just as I was about to burst with anxiety, Gene came rushing by. May stopped him. His face was covered with greasepaint and he wore neither shoes nor shirt. The stage manager was calling the overture and Gene, on a split-second time schedule, scarcely took note of me. Just a curt, “How do you do, Miss Franklin. Nice to meet you.”

In my eagerness to impress Gene, I had dressed as though I were going to tea at Buckingham Palace. I wore my slim black taffeta molded and graceful with flying paniers and I was decked with jewelry that jingle-jangled. over all this, I wore my luxurious beaver coat slung carelessly about my shoulders.

I consoled myself with the fact that Gene had been rushed. I told myself that he surely would call me. He had to! For there was nothing more I could do. I was acquainted with no one else who knew him.

The following Wednesday, my break came. After my matinee, I found a note in my theater box. Gene had seen my show, had tried to phone me without success and wanted me to have dinner with him. He gave his number.

I whooped with joy and ran back to tell the other kids in the cast. But before I reached the dressing rooms, I began to wonder . . . The other dancers in “Hattie” knew how I felt about Gene. Had they written that letter as a gag? That night and all the next day I eyed everyone suspiciously. But finally, unable to contain myself any longer I dialed the number. Gene answered the phone.

We talked for a half hour. Gene told me that May Kelly had raved about me for a solid week, insisting that he see my number in “Panama Hattie.” I listened avidly to all he said—especially when he talked of himself, building up a careful backlog for future conversations.

The next night we had dinner together. I wore the red fox jacket. He looked at me strangely, for a minute, and only then did he connect me with the girl with whom he had flirted. The beaver coat I’d worn to impress him had almost cheated me of the chance to know him.

We talked so much that night we hardly ate at all. I remembered Gene’s likes and dislikes and used them as guideposts for our conversation. I knew that, at fourteen, he had worked after school at the Robert Montgomery stables, exercising and feeding the horses. His interest in sports amazed me. And when he said that he was interested in skiing, although he had never been on a slope in his life, I immediately was eager to ski, too.

Gene took me at my word. Soon afterwards, when a group from the Ice Show went to Bear Mountain, he invited me along. The first night at the Inn he walked me to my door and kissed me goodnight. He was going to get up early next day, he said, and try his skill alone.

I hardly slept wondering how he would make out on that steep white slope. At seven the next morning, I stood at my window peering at a lone figure struggling up, up, up. About half-way up, he turned and shussed straight down, ending in a snow drift. Watching him dig out I decided that if he was going to risk his life, I was, too. I put on my red woolen “long-johns,” a pile of sweaters and struggled into my borrowed ski suit.

My boots were heavy and clumsy and when I tried running across the snow, I could manage only a slow trot. Gene, helping me on with my skis, promised to teach me whatever he had learned.

I made a brave attempt to “herring-bone” up the slope. The trick is not to cross skis in back. My skis crossed. I slipped backwards and must have fallen at least five times before I reached the quarter mark. I was hot and unhappy. But Gene wouldn’t let me remove any of my sweaters. Deciding to try again, I pointed my skis, and took off. I picked up speed, saw that I was headed towards a bump in the slope and, not knowing how to turn, I sat down. One ski dug into the snow and my body turned over. It was like a mild electric shock. I was afraid to move.

Gene removed my skis and helped me up. I winced as I tried to step on my right foot but I didn’t let him know how much it hurt. Slowly, we walked back to the Inn for breakfast.

That night, in a tub of water, my knee swelled to twice its normal size. When Gene saw me limping downstairs, he was concerned and called the doctor. I had wrenched my knee, the doctor said, but nothing was broken. My “snow bunny badge,” Gene called it.

Neither Gene nor I have been near a slope since, although our ambition is to spend a week at Sun Valley. It’s more Gene’s ambition than mine really, but I’ll be there pitching—and falling, no doubt.

Gene’s athletic prowess often discouraged me in those first days. He was a whiz at riding and skating. And the first time we went swimming, he turned out to be a Champion diver. I managed to stay in the running but obviously I couldn’t keep up with him. I thought everything Gene said or did was wonderful. When I’d known him a week, I told myself he was the man for me. Until this time, I’d been dating a boy named Chuck. Friday being our date night, he had introduced me to his friends as “My girl Friday.”

Friday night, over a drink at the Stork Club, I told Chuck, “I don’t think I can be your girl Friday any longer. I’ve met someone else and I think it’s going to be serious.”

“If you think that, I wish you all the luck in the world,” Chuck said.

Gene, too, believed our romance was serious. Later, I discovered that after our first date he wanted to give me the little golden ice-skate with a tiny diamond in it which he wore in his lapel. But his roommate suggested he wait and find out if he was really sure. So Gene waited—for two months, then had the golden skate made into a pin for me.

I’ve always let Gene know how much this pin means to me. Because it was his first gift, it’s my favorite. I lost it once, and Gene and I spent hours retracing our steps across Broadway, searching the sidewalks, the curbs, the gutters. Then we went back to the theater and looked in my dressing room. When Gene found the little gold skate under my dressing table, I was so happy, I cried.

People say you shouldn’t wear your heart on your sleeve. But a blind man could have seen the crush I had on Gene. I’m not very good at hiding things.

Certainly, I never made any bones about the fact that I was trying to please him. After Gene said he liked the way I looked in red I wore red often. When he told me he liked tailored clothes and singled out a brown gabardine suit which I wore with a brown snap-brimmed hat, I bought all the tailored suits I could afford. When he admired my hair, I started brushing it vigorously, until it gleamed, and wore it in as many different styles as possible.

One of the first things I discovered about Gene was his love for music, ballet music especially. Always, before a ballet company came into town, he would order tickets. And I would buy all his favorite records so we could listen, hours on end.

Whatever Gene does, he does well. When he became interested in painting, he would buy a book on the lives and work of the various painters, read through it rapidly and remember practically everything he had read. I read slowly, retain less than Gene. So I would make up for what I couldn’t get from the books by visiting the Metropolitan Museum.

One thing I’ve always done well, though, where Gene is concerned, and that is—listen. Everything he’s ever had to say has interested me. If it hadn’t, I’m afraid I would have pretended like mad.

FROM the beginning, we dated steadily. My mother could never quite understand how we found so much to talk about. Except for matinee days, we spent every afternoon together. After our evening shows, we’d go dancing, to the movies or just talk. Gene would take me home and we’d talk more. He’d kiss me goodnight, and then, as soon as he reached his hotel, he’d telephone. And we’d be on the wire for as long as an hour.

Soon, marriage became part of our plans.

We talked about marriage, and we talked about children. I said that when I was married, I wanted a boy and a girl. Gene said he thought that would make a nice family. He also said he wouldn’t marry until he could support a wife with ease.

Then the draft came. Gene was eligible. My friends said the usual things: “Don’t marry now . . . suppose you have a child . . . suppose he’s killed . . .”

His friends said, “Marry her right away.”

Gene said, “If you don’t marry me now, I won’t guarantee whom I’ll be seeing while I’m in the Army—or that I’ll be single when I return.”

A wave of panic swept over me. “I want to get married right away.” I proposed. “Are you sure?” he asked sternly.

I nodded, blissfully.

We were married within the week, on December 22, 1941, at New York’s City Hall.

Gene took me to the Belvedere Hotel, where he lived, and carried me into his room lighted only by the soft glow cast by the Christmas tree bulbs. Then and there, I made a vow. I had won Gene by being interested in the things that interested him. My wedding ring, I promised myself, would not change this. I’d try always to be all things to the man I loved.

When Gene was in the Army, I sent V-mail letters regularly. I told him all the details of my life, showing him not only what I was doing, but that he was constantly in my thoughts. Happily for me, Gene did the same thing.

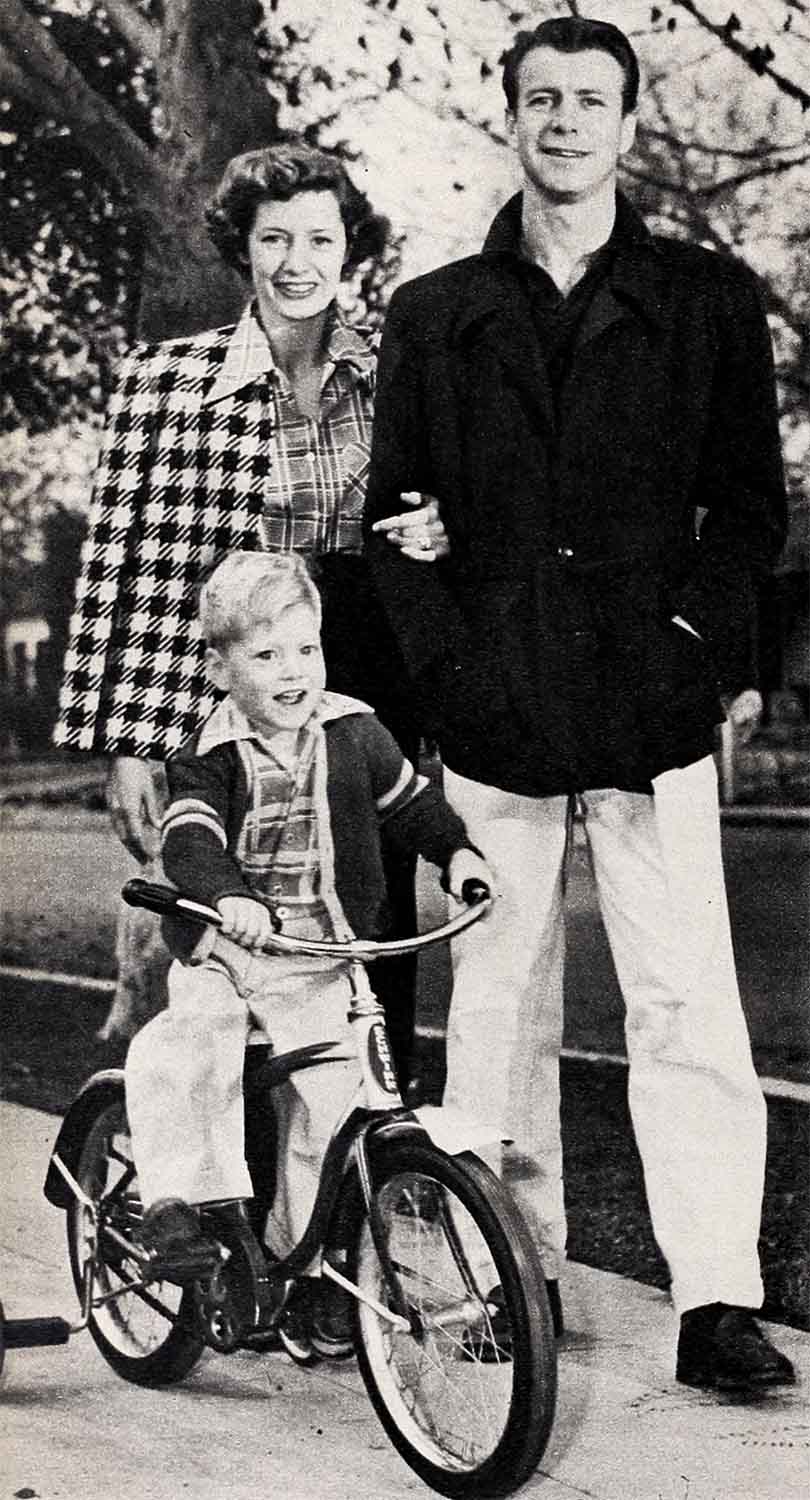

I’ll always wear my heart on my sleeve for Gene. After children arrive, some women relegate their husbands to a secondary place. Gene and I and our four-year-old son have a wonderful relationship in which Chris, product of our love, shares equally in our affections. But Gene and I love each other first.

I still help Gene with his dancing, often working on the choreography of his pictures, rehearsing with him and other members of the cast. His only objection is that he feels I, too, should be in the limelight. He dreams of us as dancing partners. I’d be happy with that kind of achievement, of course. But I know of no achievement, of no career that can be more wonderful than that of pursuing a husband—even after you’ve caught him.

THE END

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE JULY 1951