Those Lucky Ladds

It had been a great day—and there was nothing wrong with this particular night, either. The California moon hung like a gold medallion in the velvet sky, dappling the pool below with sequins. A breeze from the sea teased the olive trees on the terrace of the big house, which was dark because it was well past midnight. Before a wide glass expanse framing this view two very tired but extremely happy people, Alan Ladd and his wife Sue, lounged back on a love seat, silent and thoughtful.

They had been awake since six o’clock that morning, when Alan restlessly got down from his berth on the Santa Fe Chief to stare out the window, virtually counting the ties as he clicked toward home. He had practically wrestled the porter for the bags as the train finally stopped. When Sue protested, he grumbled, “You don’t want him to break his back, do you?” But it wasn’t only that, she knew. Her husband couldn’t wait to get his feet on home soil again.

He had raced up the ramp with Sue, Davy and Lonnie panting in his wake, expecting to find Carol Lee and Laddie at the top, of course, and Jerry with the family car. But when he rounded the turn into Union Station he couldn’t believe what he saw. There must have been sixty of them—all his best friends—down to meet him at the unlikely hour of eight A.M., some from as far away as San Diego, all yelling his name, swarming over him, pounding his back, hugging the kids, kissing Sue. That was when he lost his voice and his sight, too, as his eyes filled with the stuff a man is not supposed to show.

“Come on,” he had finally choked. “Come on out to the house. This is what I’ve been wanting so long I could taste it. Let’s make it last.” And so they had—all of them—and throughout the day twice their number more, streaming in and out of the hilltop place with the wide open door. There were big stars like Bing Crosby and Van Heflin, shy characters like stunt men to wring his hand and say they were glad he was home.

Now they were all gone. The kids were long ago in dreamland, and Beret, the dachsie, snoozed on the rug. But the spell lingered. Alan wasn’t sleepy.

“Susie,” he said at last, “you know something? We’re just the two luckiest people in this whole wide world!”

As an actor, Alan is at the summit of a career he never dreamed could climb so high. Last year, he starred in Shane, one of Hollywood’s great pictures. Hollywood’s foreign press has elected him the most popular actor in the world and he collected the top star accolade in England where he was immortalized in wax at Tussaud’s Museum along with history’s great. In America Alan nestles securely near the top of all fan and box-office polls. At home Belle, his secretary, works furiously to keep up with mail which mounts out of control. Three Alan Ladd pictures are headlining theatres at this minute with two more on deck.

Privately, his picture is every bit as rosy. Alan could support his family comfortably if he never faced another camera. He doesn’t owe a penny to anyone. Besides his luxurious modern house, he owns a dream ranch free and clear with two ranch houses. He is raising horses and chickens and the sale of eggs is now starting to show a profit. He has healthy annuities almost paid up, and some blue-chip securities. Most valuable of all, he has Sue and their family—four wonderful children, Carol Lee, Alana, Laddie and David.

Alan Ladd has just treated this family to a fabulous excursion—a grand tour of Europe lasting almost two years, all expenses paid by his employers, only because he had been working. The Ladds couldn’t have a brighter outlook.

Yet the same night that Alan Ladd voiced his appreciation of all this an anxious frown furrowed his brow.

“Here I am back home,” he worried, “and I’m out of a job!”

Sue Ladd didn’t smile at that—maybe she should have. But she couldn’t, even though they were both aware of the twenty-seven scripts stacked in his den, the producers who’d kept the phone hopefully hot even that first day home, the contracts at Warners and Paramount still in force and The Covered Wagon that had been put off and off until he could make it. Sue didn’t smile because she knew—ridiculous or not—that worry was incurable with this strange, still unconvinced man. She remembered the first day he came to her agency office, after she’d caught him on a radio show and called him in. “Pictures?” he’d said, “Not me. I’m not the type for pictures.” She’d talked him into a try, fallen in love with him, ‘married him and helped him to the heights—but she’d never convinced him. Not she nor anyone else. No matter if he lived to a hundred, and won an Academy Award each year, Alan wouldn’t ever actually believe that he rates what has happened to him. “I’ve got no business being an actor,” he’d protested how many times? “I should be out somewhere shingling a roof.”

“Come on, honey,” she said. “Let’s go to bed. You want to get out to the ranch early tomorrow, don’t you?”

He was gone before she awoke, leaving a note pinned on the rumpled pillow. “I’ll take you tomorrow,” it read. Sue grinned. That was like Alan. Maybe something was not in apple pie order and Alan always had to have that place picture perfect. The ranch was more than his hobby. It was security, the first property he’d ever owned in his life. Now he was on his way to make sure it was still there.

He was on his way fast—too fast—on the empty highway. He turned into an oak-lined country road, screeched around the pistol-shaped signpost that read “This Gun Not For Hire.” Inside Hidden Valley he slowed down to savor the familiar fields, barns, whitewashed corrals and gateposts. On the far side was Alsulana Ranch. He could just barely see it through the pepper trees. Soon he was rolling up the drive under those ancient trees, and Tex Richards, the foreman, was creasing his leathery cheeks in a welcoming grin. “How’s it look, Alan?”

“It looks great,” he said, “just great, Tex. Prettier than I’ve ever seen it. Maybe,” he laughed, a little ruefully, “I should go away more often I’ll just mosey around,” he added.

After that Alan sat on the big front porch looking out over the valley. Across the road in his pasture he could pick out the grazing horses, Judy, Alsuladd, Alanadave and old Lucky, his first, homeless horse and the reason, he used to kid himself, that he bought the ranch.

After a while he went into the ranch house. There was the coppered kitchen they’d had so much fun fixing up, the big oak table nicked with ranchware and, as he remembered, usually flooded with milk from knocked-over tumblers. In the bedroom he looked up and chuckled, remembering the day he and Sue had suddenly grabbed trace chains and whaled the too-new beams to make them look old. He walked out and strolled about the ranch. First up to the bunkhouse on the slope where the kids had grown up. Then over to the barn where he’d quartered the budding racehorse string that never bloomed. Down to the pool and barbecue, where he had once heard Jezebel barking and David crying. He had killed the coiled rattlesnake just in time. The chilling memory sent his eyes to the hillside where the bulldozer had been working that other awful day when Alana toddled away from her nurse. Jez was with him then and the boxer suddenly yelped and shot away like a bullet to knock Lonnie down just as the lethal blade swept over the spot where she’d been standing. Alan shuddered and felt a pang at the same time. There was a dog, Jezzie! She’d looked sick when he left, but he’d said, “Don’t you die now, hear me? I want to see you when I get back.” But on the boat he knew it had happened, although Sue tried to keep the news from him.

Sone else was missing at the ranch—the blanket of flowers that covered the hillside. “Tex, what’s wrong with the flowers?” he asked.

“It’s a little early yet, Alan.”

“Got to have flowers. Sue likes them.” And so he ran up the highway to a nursery and loaded his car with everything he could find in bloom, spending the rest of the day setting them out. It was late when he got home with mud on his boots and jeans and an expression of assurance on his face. The ranch was in order and definitely still there. Next day Sue could see for herself.

That night, tired as he was, Alan stayed up until three o’clock wading through scripts. The next night it was the same. Daytimes he called his producer and director friends on the phone, catching up and asking anxiously, “Say, you haven’t got a script for me, have you?” When one promptly replied, “I sure have. I’ve got two. When can I see you?” Alan rushed to Sue. “What do you know?” he cried. “I’ve got me a job lined up—maybe two!”

A WEEK after the Ladds came home, Sue got a special kiss when she woke up. “What day is this?” her husband asked. “March 15,” Sue said. “Income Tax Day!”

“You can do better than that, honey.”

“Of course I can,” she grinned. “It’s the day twelve years ago that I became Mrs. Alan Ladd. All the bad things happen to you the same day,” she kidded.

“All the good things,” he corrected her, straight-faced. “Thank God for you—and for the income tax! Say, since you’re dressed—will you do me a favor? I left my cigarette lighter in the car last night.”

Sue stepped out to the garage. She didn’t get to Alan’s car on the contrived errand because another one blocked her way—a shiny black Cadillac. On the door handle was a huge, red bow and a dangling placard. “Susie—” it read, “Cuz I love you. It’s yours, so go ahead and kill me—‘The Daddy.’ P.S. I know we can’t afford it— but ain’t it a beaut?”

Sue Ladd lingered thoughtfully, stroking the smooth new hardtop and reading that note over and over again. Alan had to make people happy—especially people he loved—but he also had to apologize for doing it.

Anyone who has ever known Alan Ladd appreciates the paradox of his makeup. The restless, ambitious guy has sought and fought steadily for everything Hollywood could give him but he has just as consistently backed away from the big treatment and crazy capers.

When you’ve been as poor as Alan Ladd has been you don’t forget it easily. A kid who lost his father when he was a baby, rattled across the country in a creaking jalopy, Okie style, and knocked around depression-strapped California in transient camps under the stern discipline of a stepfather, does not develop a taste for high life. A boy who earned everything he got himself doesn’t treat his acquisitions lightly. A man who watched the mother he adored die before his eyes with himself still unproved and a failure, is not prone to look on his success thereafter as license for a lark. Alan Ladd literally had holes in the soles of his shoes when the tide turned for him. He couldn’t trip up a primrose path with the skin still rubbed raw.

Early in his career, Paramount sent him and Sue to New York for personal appearances and put them up at the Waldorf-Astoria. One night he ordered two hamburgers sent up to the room. But when he saw the $5 tab he couldn’t eat his. It hadn’t been long since Alan himself had been frying hamburgers and selling them for a dime in a shack he called “Tiny’s.” In those early days at Paramount the star of the picture was known to grab scenery and lift it before a razzing yell from the grips, “Hey, Alan—let’s see your union card!” stopped him. It sometimes happens today, because Al still has that union card from the days when he was a grip, and lucky to be one.

When workmen are-at Alan’s house he hustles them beers and Cokes. Sue tells of the time when he accidentally slept late one morning. Around nine o’clock she called out, “Alan, time to get up!” Back came a hurried whisper, “S-h-h-h-h—don’t let the carpenters hear you. They’ll think I’m a bum!”

When the Ladds moved into their Holmby Hills house they gave two housewarmings—one for their star neighbors, another for Alan’s real friends, the gang he had worked with for years. “This is the one I really enjoyed,” he told Sue at the post-mortem. They are the people you’re likely to see around his pool and his house today, the same ones who crowded around the train gate when he came home from Europe. They drop in constantly and Alan Ladd constantly shoves his collection of honors that Sue masses on a shelf, back into the corner. “Honey, please!” he begs. “They’ll think I’m bragging.”

This is no pose with Alan, as it is with so many stars. He packs an almost penitent urge to share his luck with the people he came from, the only ones with whom he feels really comfortable and secure. One out-of-work friend came to dinner the other night and Alan spotted a frayed collar. He left with six of Alan’s best shirts. Another unemployed photographer showed up for a swim, borrowed Alan’s best movie camera to take pictures of the Ladd kids. He couldn’t give it back. Things like that happen all the time.

From His hunger days, Alan retains a pack rat urge to save things.

“Maybe I’ll need them some time,” he says. “But I guess the real reason is that I like things I can hold in my hand.” Sue gave Alan a beautiful Audemar Piguet watch when they were in Switzerland, the finest made anywhere; only twelve a year are produced. He likes to look at it. But he wears “the watch,” a plain gold ticker Sue gave him back when they first fell in love. He’s got boxes stuffed with rings, cufflinks, and such, but he wears only his wedding band and his service ID bracelet.

You could go on and on, describing the ways in which Alan Ladd constantly reassures himself of his great good luck and at the same time backs away from flaunting it. But maybe his recent stay in Europe—the trip people said was bound to change him—shows it best of all.

Alan didn’t want to go. “Why leave here?” he answered when foreign offers came. “This is the best place, isn’t it?” In the end he decided to go but only because a European stay, en famille, had been Sue’s dream. She was educated in Switzerland and France. She wanted her kids to know how the rest of the world looked, sounded, tasted and smelled. So when producers started upping the ante and including almost every trip expense from gasoline to toothpaste he consented to pry himself loose.

Even with the house rented, everything stored, his entire family aboard the Ile de France, Alan wanted to call the whole thing off when the boat docked at Southampton.

It was four-thirty a.m. and still dark when the British reporters climbed aboard, loaded for bear. Who, they demanded, did Alan Ladd think he was, coming to England to play a British war hero? Didn’t he know that the red-bereted paratroopers symbolized England’s wartime courage?

The battery of questions was a shock. He had thought that coming over was a piece of good will between the two countries. Besides, as he tried to explain that morning, the role in Paratrooper was about an American who came voluntarily to fight in the Red Berets because he loved England. But he was so shaken by the experience that when the reporters departed he had to go back to his stateroom and lose his coffee and toast. “Let’s go on back home, honey,” he told Sue. “They don’t like me here.”

But they did. Before he left Britain Alan had conquered the place almost as thoroughly as any foreigner since 1066. He was voted the most popular star in England. But perhaps he wouldn’t have had the heart to stick around if something hadn’t happened a few days after he arrived. Visiting Shepperton studio, he sneaked on to the set of Moulin Rouge to have a look at how they did things over there. A thousand extras and workers were crowded into the place and when they set up a shout he thought he’d stumbled into a scene. But the shouting was all about himself—a welcome from his kind of people. Alan watered up that time, too, and today tags it the biggest thrill of his trip. It was the assurance that he was welcome and wanted.

But if they had turned out the guard at Buckingham Palace in his honor it couldn’t have banished the ache he packed for home. He saw new sights and like the rest of the family, he acquired an education he couldn’t have bought at home. But, as Sue noted, “All the time we were gone Alan was trying to prove to himself that he’d never left home.”

Hallowe’en came and even if the neighbors didn’t know what he was up to, he decked out the big house they rented in orange and black streamers, carved pumpkins and lighted them in the windows. He sent the kids, Lonnie and Davy, out rapping on doors and yelling, “Trick or treat!” to the astonishment and confusion of the countryside. Two nice ladies thought they were burglars and called the bobbies.

At the Paris restaurants he tasted what Sue ordered, made a face, and tried to say “bifstek” in pidgin French. He outraged porters everywhere, although he tipped them generously, because he grabbed his own bags half the time, hating as always to have anyone do anything for him. Hotelkeepers were dismayed when he asked to fry his own hamburgers.

Wherever the Ladds rambled—through England, France, Switzerland, Italy, Germany, Holland and Belgium—everything Alan saw only reminded him of what he liked better at home.

The winter sports at St. Moritz only suggested Old Baldy back home. Monte Carlo was a glittering kick (especially when he put two bucks on the dice and walked out with two hundred) but to Alan it was just Las Vegas in dress clothes. Venice was swell, but he liked the Grand Canal best skimming over it in a motorboat as he used to on Balboa Bay in California. His favorite spot in Rome was the sports forum that Mussolini built to revive Italy’s athletic prowess. That was where Alan headed late on moonlit nights, yanked off his shoes, dug starting holes in the cinder track and had Sue clock him in the 100-yard dash! Wherever they went, Sue had to find a U.S. Army PX and buy pancake mix and canned chili and beans.

To this day, Sue wonders what kept Alan from going over the hill for Hollywood when they came as close as Banff in Canada, to make Saskatchewan. When Carole Lee and Laddie took off for Hollywood from there, Alan gazed so wistfully after the kids that it wouldn’t have surprised her if she’d had to chase after him across the glacial Bow River like Eliza crossing the ice.

But there was still The Black Knight to make in England. After that, he could have played two more pictures abroad if he’d wanted to.

By that time Alan Ladd had a one track mind and it led nowhere but home. The S.S. United States brought him there, and of all the 36,000 miles he covered, that last stretch from Le Havre was the best. Two foreign flag ships sailed more conveniently but as Alan told Sue firmly, “No more boats where I have to wake you up to order ham and eggs for breakfast in French.” First thing he did aboard the floating bit of homeland was to roam around the ship treating his ears to American accents.

He was up at five a.m. to see the Statue of Liberty loom into view and his stay in New York amounted to four fast hours. That was enough to say hello to his pal, Lloyd Nolan, playing on Broadway, and to call Hannah, the cook out in Hollywood, and tell her what he wanted for dinner the night he got home—“Ham, cornbread and black-eyed peas.”

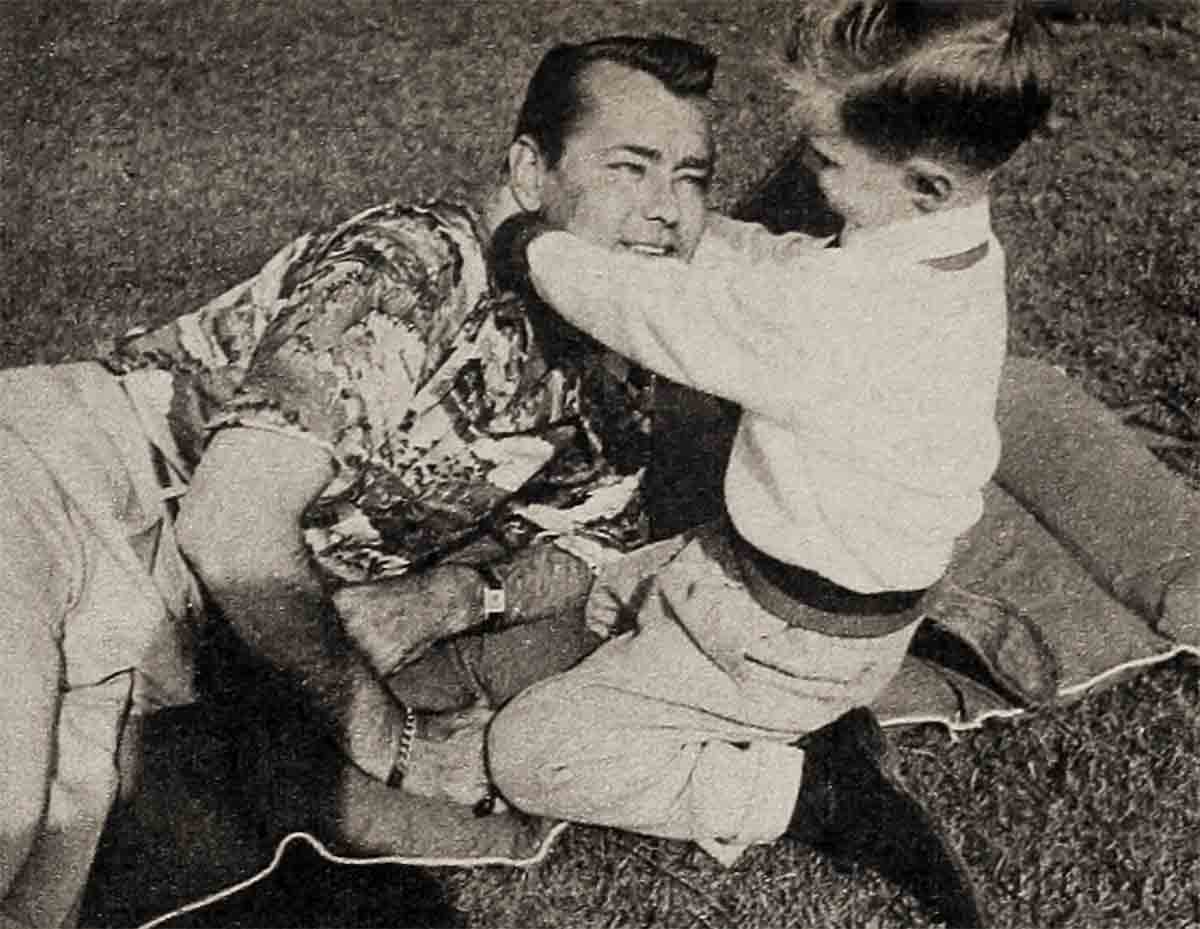

All of this is a montage of memories to Alan Ladd, very pleasant ones, but he’s thankful they’re in the past. “Look,” he said, when he was told what a lucky guy he is to have had the trip, “I’m so lucky for everything I can’t believe it. But the best luck is being right here where I belong. You planning a trip? People are people all over the world—they just talk differently. Sights are sights—and Ive seen some great ones. But there isn’t any sight better than this,” and he waved his hand in a circle embracing the things that were unmistakably his, right where he could see and touch them if he wanted to. It embraced a wiry little carbon copy of himself, named David, learning flips on the springboard just as his old man used to do. “Hit the board harder—and straighten out those knees,” shouted Alan. It took in a dainty ten-year-old doll named Alana, watching all this gravely with her chum, Katie. “Can your daddy really dive, too?” asked Katie. “My daddy can do anything,” came the withering reply.

That circle also took in a manly sixteen-year-old called Laddie who carefully polished a new Ford his dad had just given him. There was another one for Carol Lee (with apologies to his other kids, “I hope I can afford one for you, too, when you grow up.”) It embraced the big, comfortable house where Jerry and Hannah were already fixing lunch in the kitchen and Belle, in the office, was filing papers for Ladd Enterprises, which will produce pictures.

It included the ranch out in Hidden Valley. In fact it swung all around Hollywood, where Alan Ladd had grown up in poverty and miraculously found his future and his fortune.

Sue came in. “Your agent’s on the phone. He says there’s an offer for you to make a picture in Boston.”

“Boston?” teased Alan. “Where’s that? If it isn’t in Hollywood the answer is no Honey, you know I don’t like cod.”

“Now, Alan—”

“Yeah, I know. Tell him I’ll call him back ”

Alan sighed. “Sue’s still the boss around here,” he grinned. “I guess she always will be.” And I thought of a remark a friend of Alan’s once made to me. “There isn’t a star in Hollywood who’s handled his success better than Alan Ladd, and nobody’s handled Alan better than Sue.”

It’s a case of two heads and two hearts together which have brought the good things that Alan meant when he swept his arm around and said “all this.” The winning combo is no more likely to change than Alan Ladd is. If twelve years in the pressure cooker of Hollywood can’t do it, a trip to Europe won’t turn the trick.

THE END

—BY JACK WADE

It is a quote. MODERN SCREEN MAGAZINE JULY 1954

No Comments