From California To London To Bedlam

The earth was covered with a thin blanket of gray snow and even the buildings of the London airport were half hidden by the heavy mist; the sky was the color of lead.

Jeanne Crain shivered and put her hands in the pockets of her heavy coat as she waited for the New York to London plane. She was waiting for her husband, Paul Brinkman, and their four children to begin a three-month European jaunt.

Blowing on her hands to keep them warm, Jeanne watched the sky carefully.

“Cup of tea, ma’am?” the airport attendant asked her.

“No, thank you,” Jeanne said, not wanting for one minute to miss the plane.

Meanwhile, on the New York to London plane, Paul Brinkman muttered under his nreath as he tried to dress his three youngest children—a feat that can only be accomplished in the lower berth of an airplane if both parties are lying on their backs. But Paul—who had bravely volunteered to bring all four children from California to London by himself—refused o be daunted by a few buttons.

“Daddy,” Michael asked, “where’s Paul?”

“What do you mean?” Paul asked, buttoning the last button on Michael’s weater and reaching for his comb.

Michael is six years old and casual about most things. “He went to the bathroom last night and he didn’t come back.”

Paul sat up quickly, hitting his head for the third time against the top of the berth. Be looked into the aisle of the plane. Two-and-a-half-year-old Jeanine and four-and-a-half-year-old Timothy were sitting in the middle of the aisle rolling marbles at each other. They were a hazard to traffic, but at least they were there.

Paul Brinkman Junior, who is tall for his seven-and-a-half years and quite conspicuous, was nowhere. He was not in the men’s lounge or the women’s lounge, not in the galley, not sitting with any of the other passengers. The escape hatches were still bolted. No one could have left the plane, and yet Paul was not in the map room, not up front with the crew, not in the rear with the baggage.

Paul ironically remembered his last words to his wife over the long-distance telephone wires a few nights before. “Don’t worry, darling,” he had said. “One good thing about a plane. The children can’t get out.”

The plane was checked and double-checked. The other passengers looked under their seats and their suitcases. No Paul. And all the berths had been made up except one.

“Maybe he’s in there,” Paul suggested to the stewardess.

Well,” she answered doubtfully, “it’s occupied.”

“I’m going to look,” Paul said and cached for the curtains.

The stewardess stopped him. “It’s occupied by a woman.”

Paul took his hand away. Maybe you’d better look then,” he said.

The stewardess looked–and found Paul and the original occupant sleeping contentedly at opposite ends of the berth. In the dark, half-asleep, Paul had missed his own berth and crawled into the next one, and neither he nor the woman had been awakened by the search in the aisle outside.

Finally, Paul, too, was dressed, and the five Brinkmans sat restlessly in their seats. In a few minutes, the plane would be landing in London; in a few minutes, Paul thought, he would be seeing Jeanne again. Nothing could happen now.

“Daddy,” Michael said, “I feel awfully sick.”

“Daddy,” Timothy said, “I think I do, too.”

Paul and Jeanne didn’t know it then, but it was an apt beginning for this trip.

The necessity for this family honeymoon came about after Jeanne finished “Man without a Star” at Universal-International. She dyed her red hair black and went to Europe for “Gentlemen Marry Brunettes,” expecting to return home by Thanksgiving. She didn’t, and the shooting dragged on into December. Suddenly she realized that they would not be finished by Christmas. And Christmas without the family was impossible. So on that gray December day she waited at the airport. If she could not go home for Christmas, her family would come to her.

The plane landed and the first thing Michael said was, “This isn’t London.”

“Of course it is, darling,” Jeanne said.

“Can’t be,” joined in Timothy. “The people look like us.”

When this slight misconception was straightened out, they drove to their rooms at the Dorchester Hotel. Paul and Jeanne thought it would be nice to have an early dinner and go to bed. They were exhausted. But the children, being normal and healthy, were still living on California time. They could not be convinced that just because it was 8:30 in London, it was time to go to bed. For two weeks they stayed on California time and went to bed at one A.M. And, of course, for two weeks they stayed on California mealtime. According to Big Ben, they had breakfast at eleven, lunch at 4:30, dinner at eleven.

The first night, just before he went to sleep, Paul called to his mother. “We still get bicycles for Christmas,” he asked, “don’t we?”

Jeanne thought of crating, uncrating, transporting and caring for two bicycles on various stages of the journey from London to California and shuddered. But Michael and Paul had been promised bicycles for Christmas. “we’ll see, dear,” she said. “We’ll look in the toy shops tomorrow.”

The toy shoos were crowded with things.

“Here’s something.” Paul showed a beautiful—and light—erector set to his oldest son. “You can make three hundred things with it.”

“Nice,” Paul Jr. said. “Where’re the bicycles?”

“Look, Michael,” Jeanne said. “Here’s a punching bag.”

“Swell,” Michael said. “But let’s see the bicycles.”

Timothy ran down the store aisle. “Where,” he asked, “are the tricycles?”

Christmas Eve found Paul lugging three crates full of bicycle parts from the basement of the Dorchester Hotel to their suite. When he had carried the crates up, he and Jeanne sat on the floor and assembled the pieces. By three A.M. Christmas morning they had two beautiful English bikes, a tricycle for Timothy and a sidecar that could be attached for Jeanine.

Paul Brinkman kissed his wife. “Merry Christmas,” he said—and stumbled against the handlebar of Michael’s bike. “Honey,” he said, “are we crazy?”

They are crazy, but it is a nice sort of amiable insanity—the kind that made them take four children to Europe without a nurse or maid, that made them buy antiques and bicycles without a thought of how they would get them home, that allowed them to entrain recklessly for the United States with eleven trunks, eight suitcases, twenty-two crates and four children.

During the weeks in London, Anglo-American relations proceeded quite well. Of course, Timothy and Michael wondered why the English spoke French.

“It isn’t French, stupid,” Paul Jr. said to Michael. “It’s English.”

“You can’t fool me,” Michael said.

The Brinkmans spent most of their days in Hyde Park, the beautiful London park that is twenty-one miles long and that—luckily for Paul—is just across the boulevard from the Dorchester. Luckily, because part of his job as a father was the daily carrying of two bicycles, one tricycle and sidecar over to the park and back.

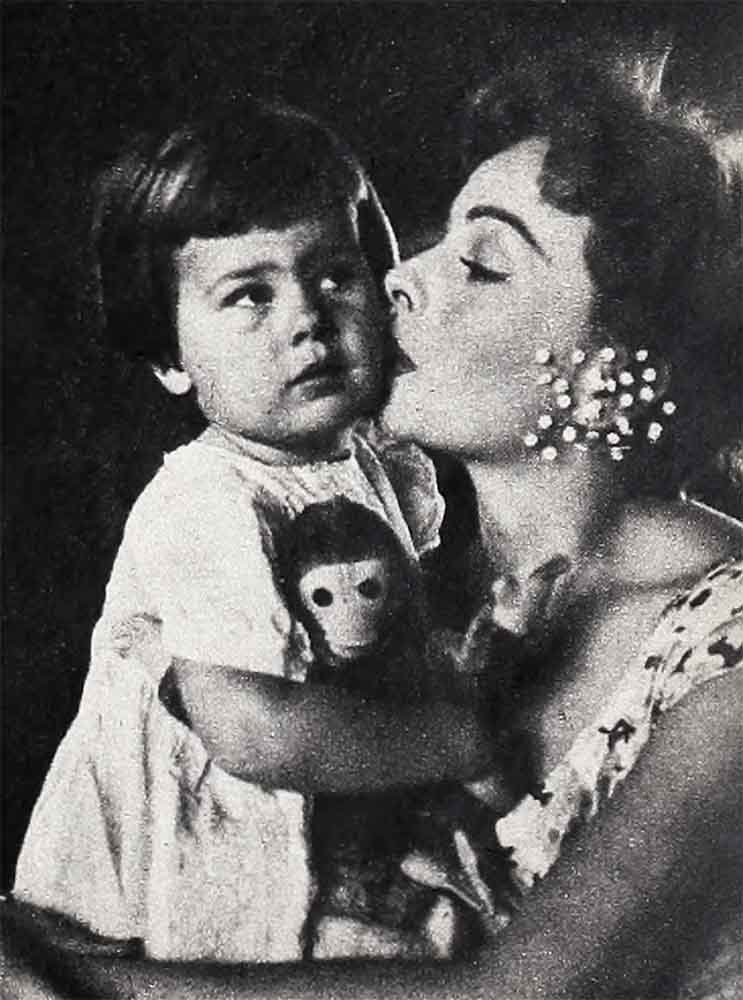

The park had lakes with white swans that got fat on the remains of children’s breakfasts and teas. Soon the Brinkmans began stuffing things in their pockets to feed the swans. All expect Jeanine. She stuffed the bits of egg and rolls and squashy jam cakes into her pockets all right, but she forgot what she was supposed to do with them. Once, when she wore the same sweater for three days, all the animals in London followed her home.

The evenings, at least, were for Paul and Jeanne. They walked through Hyde Park, listened to Big Ben sound the hours, stood and watched the Thames flow by, drove through Piccadilly Circus with the wind blowing against their faces, danced in small clubs and, often, just stood for a moment and looked at the streets around them—the streets that had in their past so much of history.

It was, as Jeanne had said, almost like a honeymoon—except for the few problems that normally don’t crop up on honeymoons. Like the night they came back to the hotel, their hair still wet from the fine London mist. They were cold and out of breath. Paul prodded the embers of the fire in their sitting room. When the fire flamed again, they sat on the floor in front of it, shaking the dampness from their hair. They were silent for a while, and Jeanne laid her head against the couch and felt the warmth of the fire on her.

“Ten more days in London,” Paul said. “And maybe we weren’t so crazy after all. We haven’t lost any children.”

He paused, and Jeanne nodded sleepily. “. . . they haven’t gotten sick.”

Jeanne nodded again.

“. . . and their noise hasn’t even gotten us evicted from the hotel.”

The door to the sitting room opened, and Timothy came in. “I don’t feel good,” he said. “My throat hurts and my head hurts.”

The doctor was called and said it was probably mild tonsillitis aggravated by the London weather. Timothy would be all right in a day or two, he said. Then Timothy was put back to bed.

Paul and Jeanne slept late the next morning. Through their blanket of sleep came sounds of laughter from the boys’ room.

“What’s wrong?” Paul asked sleepily.

“They’re playing,” Jeanne said. “Isn’t that nice?” She pulled the blanket over her ears.

Fifteen minutes later, Michael came into the bedroom and jumped thoughtfully up and down on the bed.

“ ’Morning,” he said. “Gee, Timmy looks funny.”

Timmy’s parents bounded like deer from the bed. Five minutes later, it was obvious to them that Timmy had the mumps. The other boys were quickly shuttled off to other rooms.

“Not,” Paul said, with resignation, “that it’s going to do any good.”

Day by day the time of leaving came closer. Timothy recovered and still the other children felt fine. Jeanne and Paul had nightmares about the other three children breaking out with the mumps in the train to Southampton. They had nightmares about the inspectors examining the children and then quarantining the family in England for weeks.

“Don’t,” they told the children, “say that Timmy’s had the mumps. It’s in our papers. We just don’t want to remind the inspectors.”

The packing of eleven trunks, eight suitcases, two bicycles, one tricycle with sidecar, an antique dresser, copper for fifty antique lamps and a few assorted odds and ends did not help their nightmares any.

Paul hammered his thumb for the third time and put it in his mouth to ease the pain. “You must be crazy,” he mumbled, “asking me to bring four kids to Europe.”

“Me?” Jeanne tried to repair the fingernail she had torn on Michael’s bicycle seat. “Me? Who said there’d be nothing to it?”

“Any sane man—” Paul began.

“Any sane man,” Jeanne said, “would have kept his child from playing with someone who had the mumps.”

“Any sane man? Why there’s no one in this whole city who’s got the mumps except Timothy. He must have caught them out of nowhere.”

There was silence for a moment.

“And how the blazes,” asked Paul, “are we going to have room for fifty copper lamps in our house?”

“I’ll find room,” she said defiantly. Then she thought about the house with copper lamps suspended from the ceilings and copper lamps rising out of the floors and copper lamps strategically sunken in the swimming pool, and she started to laugh.

Paul looked at her angrily for another minute, and then he started to laugh, too. They sat on the floor of their Dorchester apartment, surrounded by half-closed packing cases and pieces of straw and laughed until the laughter was too painful for these two sane adults to stand.

Paul reached for her hand. “We don’t even have enough sense,” he said, choking on his own laughter, “to fly back. No, we’re going to take a five-day boat trip so that. . .”

They said the words together, “. . . so that Michael and Timothy can see the whales.”

Jeanne was helpless against the laughter. “You had to take them to see ‘Pinocchio.’ ”

“How was I to know they’d fall in love with a whale? And anyway, you were the one to say we’d seen whales when we came over in October.”

“You had to buy them bicycles.”

“You had to buy enough antiques to fill eight packing cases.”

“And you had to decide to drive the rest of the way back from Chicago.”

“Why was that?” Paul asked firmly.

“Because I wanted a new car. Thank you, darling,” and in the same breath, “I’m sorry.”

‘What for?” Paul was serious for a moment. “The people who aren’t crazy miss an awful lot.” He held out his arms to his wife.

She rested her head against his shoulder. “We are idiots,” she said thoughtfully.

“But happy?” he asked.

“Very happy,” she said, as the staid old Dorchester creaked a little at the sound of laughter before settling back to normal.

Eventually the packing cases were all nailed and the trunks packed and the suitcases locked, and a strange procession crossed the Dorchester lobby. Attached to Jeanne’s left hand was Jeanine, dressed completely in red; attached to Jeanne’s right hand was Michael, dressed in green. Paul had Paul Jr. in blue and Timothy in yellow.

“It was the only way,” Jeanne has said, “that we were able to out the right cap and mittens on the right child.”

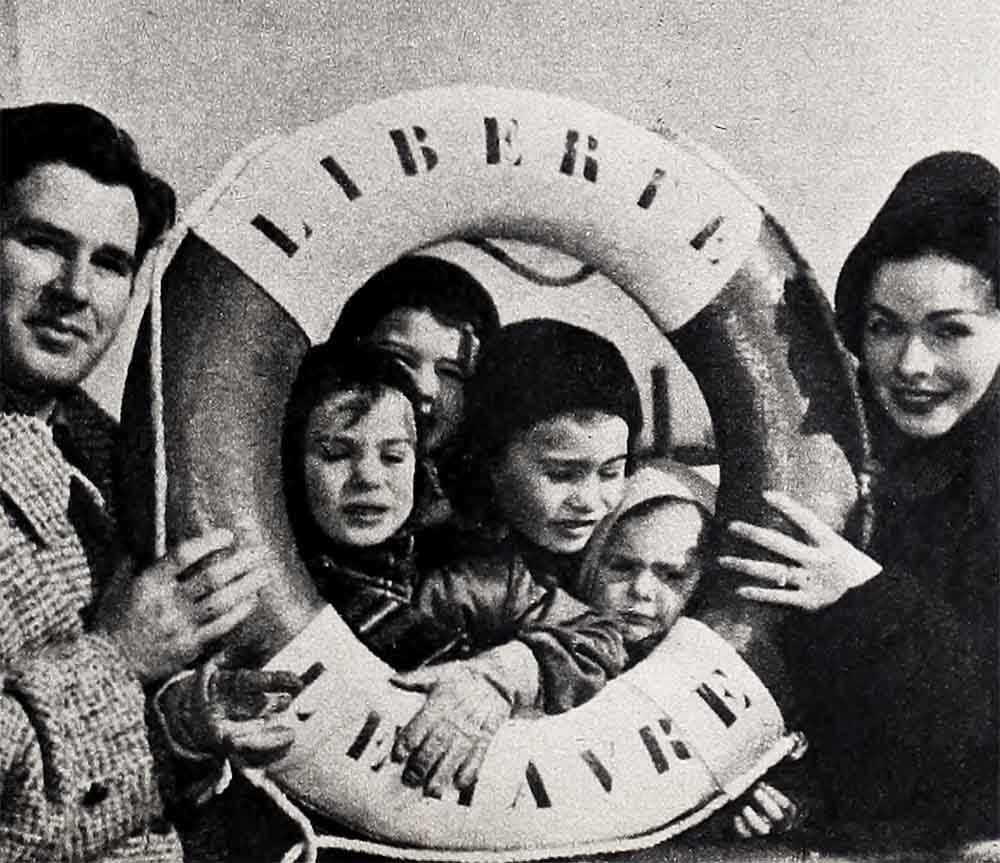

Strung out behind like a native safari in darkest Africa were a group of porters. They got aboard the boat train all right. The real troubles began at Southampton. The tender which was to carry them from shore out to their ship, the Liberte, was broad, and it lacked rails. It was flat and ugly, and it looked like a disreputable ferryboat. Jeanne sat on the lowest packing case, looked at the stormy Atlantic and held tighter to the two children.

A voice approached out of the fog. “We just had to see you off. Have a good trip.”

Jeanne looked up to see a large and bulky basket of fruit descend on her. She let go of Michael and Jeanine just long enough to tuck the basket under her left hip and smiled weakly at their friends. Then she crossed her fingers and hoped for the best.

The best, however, was not to come. The last minute gifts placed at the shrine of the departing warriors included two orchid corsages (one of which Jeanne pinned to her coat, the other of which perched limply on her hat); six novels (“to read on the trip; you’ll be frightfully bored otherwise”); several boxes of candy (which at least kept the children interested in something besides the Atlantic for a few minutes); and a large bunch of flowers for their stateroom. Jeanne thought of that stateroom on the distant Liberte in much the same fashion a traveler lost in the Sahara thinks of water.

Timothy wandered over. “Daddy’s talking to the men,” he said, pointing out the customs inspectors.

“Fine,” said Jeanne absently, pulling Jeanine down from the packing case she had started to climb.

“Where’s Paul?” Michael asked in the tone of one who feels someone else is getting privileges unfairly denied to himself.

“Looking over the edge,” Timothy said, seating himself on a packing case.

Jeanne caught her eldest son before he plunged into the Atlantic and brought him back to their home away from home on deck.

“I was looking for whales,” he said.

Paul and the customs inspectors came over to examine the luggage. Michael decided to get friendly. “We’re going home,” he said to the nearest uniform. “We’ve been in London. Lots of things happened. We went to the circus, and Timmy caught. . .”

“Look,” Paul said desperately. “A whale, look.”

His heart did not quite stop at the thought of the children being examined and perhaps quarantined in Southampton for weeks, but it came close.

“Where?” Michael asked.

“There aren’t any whales here,” the chief inspector said.

“Oh, sorry,” Paul said. “Probably just need glasses. Make a note of that, darling,” he said to Jeanne who was busy offering Michael his choice of caramels.

Then the crisis was over. The inspectors departed, and the tender rolled mournfully out of the bay.

The five-day trip to America on the Liberte was disturbed only by the necessity for typing out a customs report on the eleven trunks, eight suitcases and twenty-two packing cases. all antiques are duty-free, but you still have to list them. Jeanne and Paul were afraid they would miss some Georgian andiron or pewter mug in their list and be accused of smuggling. And when the time came, they did have some trouble. But it wasn’t over the antiques. It was over bicycles.

“Hum,” the inspector said suspiciously. ‘English bicycles. Why did you go over to England to buy bicycles?”

Jeanne tried to explain that they hadn’t—as he thought—gone to England for the express purpose of buying bicycles.

“Why’d you buy them then?” he asked patriotically.

“Christmas,” she said, keeping both eyes on Michael who was trying to pick the lock on someone’s trunk.

“American bikes aren’t good enough for Christmas presents?”

“No. Yes. But we were in Eng. . .” She pulled Timothy away from a shipment of Asiatic snakes. Paul did a better job of explaining, and in the end, they were allowed to go.

And for once they were lucky. The boat docked on time. Two hours after landing, they were aboard the train to Chicago; the train left on time. The trunks and packing cases rolled safely to California via the Southern Pacific. Only the six Brinkmans and eight suitcases were foolish enough to leave the train. Paul picked up Jeanne’s new orchid-and-white Oldsmobile in Chicago and they started the three-day drive west.

As if to impress them, the weather was doing some of the most peculiar things it had done in fifty years. An hour out of Chicago a blizzard (“Ain’t never seen a blizzard this late in the year,” a filling station attendant said with awe) we comed them. The kids adored it.

“Snow,” Paul Jr. said. “Real snow.”

“Snow,” Michael shouted, putting his hand out the window to catch some.

“Hey, it’s all wet,” Timothy said, wiping his snow off on Jeanine.

Jeanine began to cry.

The blizzard was followed by a spring flood. Paul turned on his windshield vipers and struggled desperately to see the road.

“It’s rain,” Paul Jr. said.

“Raining hard rain,” Michael offered, opening his window.

“Swell,” Timothy said, getting his sweater soaked in an effort to catch the rain.

The rain hit Jeanine in the face and she started to cry.

The rain was followed by washed out bridges, a rockslide, three detours and a roadblock. Finally, an hour late and fifty miles out of their way, they limped up to a motel for the night.

The next day dawned cool and clear.

“Thank God,” Paul said, looking at the sunlight shining on the highway. “No trouble today.”

He was slightly mistaken. Around noon, Paul Jr. complained of a sore throat, Jeanine began to cry and Michael said his head ached. By three o’clock it was obvious that three more children had the mumps.

“Everything’s happened on this trip except a sandstorm,” Paul said to Jeanne as he stopped for orange juice for his feverish children.

He hadn’t learned—even yet—to be silent about his good fortune. There was a large desert between him and California and while driving through the middle of it there occurred a genuine sandstorm.

The children were over most of their fever by that time, and they sat, happy and swollen-cheeked, in the rear seat.

“Great,” Michael said. “Look at that dust.”

“That’s not dust, dopey,” Paul said. “That’s sand. Isn’t it, Daddy?”

Timothy merely sat and sang contentedly to himself, “You’ve got the mumps. You’ve got the mumps.”

But all things—even the wrath of the gods—must come to an end and, at approximately 11:03 P.M. that evening, the Brinkmans drove up the winding road to their canyon home. all of them—even Jeanine—stood quietly for a moment, looking at the silent house.

“Hey, Mommy, we’re home,” Michael said, and there was a note of awe in his voice. And Jeanne knew exactly what he meant.

After the children were put to bed, Jeanne and Paul raided their own kitchen. Jeanne’s mother had stocked the house with eggs and bread and milk, so they made hot chocolate and an omelet. They skirted the trunks and packing cases, which the Southern Pacific had left in the middle of the floor, and took their food out to the porch, to sit and look at the city dropping away beneath them, lighting up the bottom of the hill.

For a while they sat quietly, listening to the crickets and the rustle of leaves.

“Well, it’s over,” Paul said. “We’re home. We’ll sleep in our own room, and no one will wake us with a cup of tea. Are you glad?”

“Yes,” she said. “I never want to see another lower berth or another stateroom or another trunk—not for a while anyway.”

They walked among the packing cases in their living room.

“Just one job left,” he said. “Tomorrow we’ll have to open these.”

“Tomorrow?” Jeanne asked hesitantly.

“Well, I’m not going to open them tonight And besides, I thought you never wanted to see another—”

“Just one,” Jeanne said. “The captain’s table and the fireplace set. To see if they really fit here—at home.”

“All right,” he said. “Just one.”

The clock struck one, and the Brinkmans sat in the middle of their own floor and began to open packing cases. The hammer slipped and hit Paul’s thumb. He looked at his finger thoughtfully for a minute and then smiled.

“It’s good to be home,” he said, bending over and kissing his wife. “Welcome home.”

THE END

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE JULY 1955