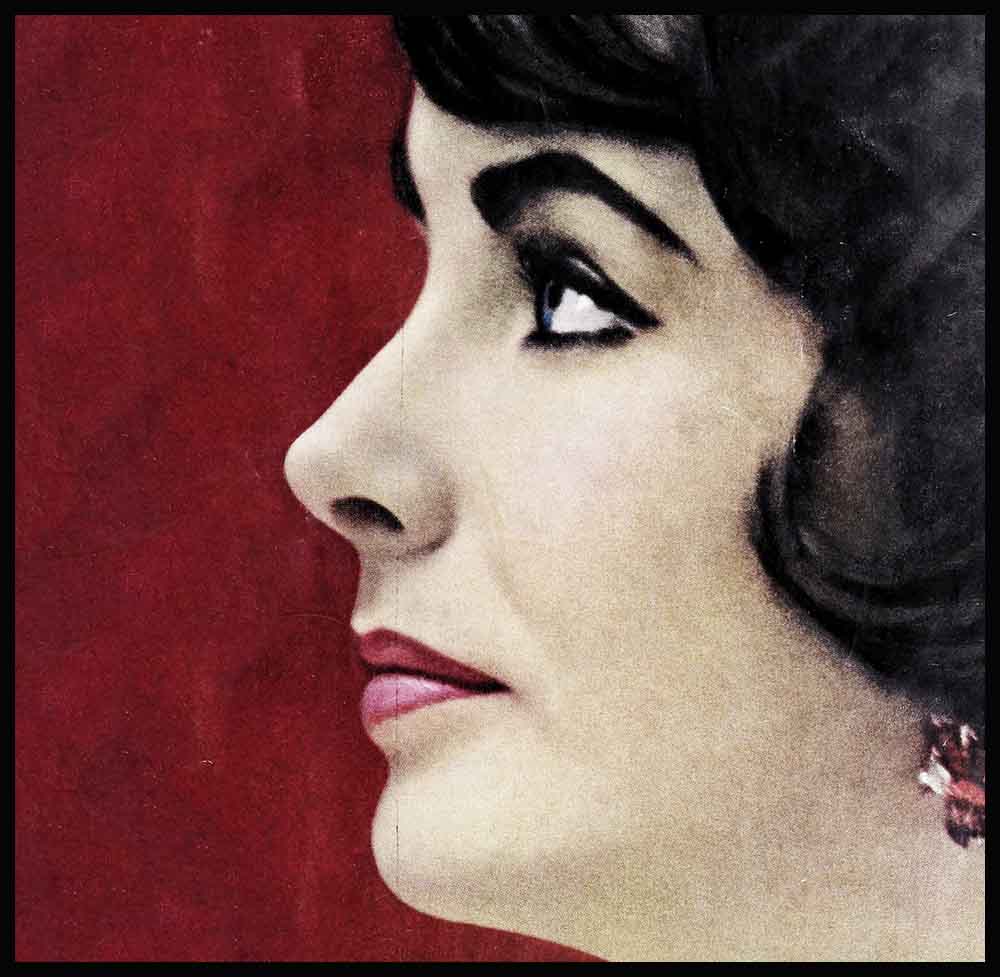

How Much More Can Elizabeth Taylor Take?

It was their first anniversary. Alone in the room, Liz was crying. Where was Eddie?

He’d said he would be back soon. Suddenly her pet monkey, Matilda, cut across the room and jumped up on the couch. Liz almost laughed as the little monkey thrust her impudent, small head up to be scratched. Smiling, she stroked behind the monkey’s ears, but her thoughts were far away. For a moment, the bright afternoon light from the window, shown directly on Liz’ face—a tired face. red and slightly puffed with tears; and the sun also glinted on the huge photograph of Mike Todd that stared down on her from the wall. Her hand mechanically rubbed Matilda’s ears and the sparkle from Mike Todd’s $92,000 ring, on her finger, moved back and forth. It seemed even brighter against the dark hair of the monkey. All was quiet, and then a sudden harsh sound at the door made her leap to her feet. Matilda screeched in fright. Their four dogs began barking all at once, and the two cats added to the din. “Eddie?” Liz said. “Eddie?”—but the footsteps outside faded down the corridor. Suddenly, she knew it. Something had happened to Eddie. He should have been back by now. He’d said he’d be gone only fifteen minutes. “He must have had an accident,” she thought out loud. She lived in dread of this. “Don’t be silly,” Eddie would laugh, like that day on their honeymoon, when he took up the dare and played he was a matador, making cape-like passes with his scarf at a harmless bull in Spain. Everyone else had laughed; even Eddie had laughed; but her heart had stopped beating—she was certain it had stopped beating—for a few seconds. “Suppose it isn’t harmless?” she had said. “Accidents can happen any time.”

AUDIO BOOK

She looked up suddenly at Mike’s photograph, bringing her thoughts back to the present.

Her eyes studied the calendar tucked into the corner of the blotter on their desk. It told her what she already knew so well: this was May 12, 1960, the first anniversary of her wedding to Eddie. She unconsciously turned over the calendar months, one at a time, and maybe, because she was alone and afraid, she remembered things she had tried hard to forget. . . .

May, 1959. She remembered the wedding in Las Vegas but somehow today the excitement and the beauty of the ceremony was just a fuzzy blur, and what she recalled was something else; something she thought she had put out of her memory forever. The reporters and photographers were crowding around her. The ceremony was over. Someone yelled congratulations and they applauded and for a while— for just a little while—she felt they liked her, that they really wished her and Eddie the best.

“What do you have that’s old, Mrs. Fisher?” a reporter shouted.

She showed them the heirloom handkerchief she was carrying. It had been in the family for years.

“And what do you have that’s new?”

She looked down at her moss-green chiffon wedding dress, it had been created especially for her for the occasion, and she smiled and sort of curtsied.

“Something blue?”

For a second her cheeks turned pink, and then shyly, she admitted that she sentimentally wore a blue garter.

“Anything borrowed?” a columnist asked.

And a photographer screamed out an answer. one word—and she felt that she wanted to run away, crawl away, fly away, get away and hide from them all. One word: Eddie.

June, 1959. They were in London, she was making “Suddenly Last Summer.” She remembered the press attacks—vicious, underhand, constant—made against her and Eddie by the British press: “Mr. Fisher, after accompanying his ever-loving wife to the studios, every morning, spends his days alone in their rented house (the police guard is no longer there looking after the children). Sometimes, but rarely, he is allowed to bring them over to lunch with Mother. I wonder what Mr. Fisher thinks about the price one pays for an Award-winning wife? But Mr. Fisher isn’t singing, either. Suddenly this summer, all is tension.”

She’d tried at first to keep the paper from him, but failing, she had made light of the item and laughed it off. Eddie’s lips laughed with her, but there was nothing she could do about the expression in his eyes.

But then, later, neither of them could even pretend to laugh. One columnist revealed: “Liz Taylor’s raven tresses are already streaked with gray.” Other London reporters called her “fat.” After that she went on a crash diet that left her twenty pounds thinner, but also left her with dark circles under her eyes.

July, 1959. Unfriendly newspapers, hostile crowds, and scurrilous mail seemed to meet them wherever they went. When they left London and went to Paris, the British newspapers reached across the English Channel and falsely accused them of “ducking out on rent and food bills.” In their suite, in the French Capital, 6,273 letters were waiting for them, a little less than their average weekly mail, usually. And as always, it was directed against their marriage.

One afternoon, she went out alone, behind dark glasses and with her hair covered by a simple shawl, to shop. She’d bought two kites for her boys, when the salesgirl recognized her and began chattering away excitedly in a French too rapid for her to understand. In a moment, she was surrounded by other salesgirls, and then by an ever-increasing crowd of customers. Everyone was jabbering away at her at once, and she tried to tell them, in her slow French, that she didn’t know what they were saying, that she must get back to her hotel.

She didn’t understand the words, but she did understand the tone. At first, the crowding women had been curious, but now they were angry. One stout woman, who seemed to be some sort of leader, screamed and waved her umbrella. The others seemed to be repeating what the woman was saying. They pressed toward her, and she realized that the salesgirls were doing their best to hold the customers back. “It’s a mob,” she thought, “and they’re after me.” She almost fainted.

Suddenly, the crowd stopped. Three floorwalkers and a manager pushed to her side and forming a protective cordon around her, they helped her toward the door. The stout woman took a swipe at her with the umbrella, but a floorwalker warded off the blow. Outside, they helped her into a cab and the manager rode with her back to the hotel. On the way, he explained to her, in broken English, that the “ladies” who had descended upon her in force did not represent “real French public opinion.” She thanked him, but in her heart she felt that she had just met, face to face, the 6,273 people who had sent the “hate” letters.

August, 1959. If the “ladies” of Paris were insulting, the “women” of Spain were just plain “cold” to the Fishers. A lovely house had been rented for them, in Palamos—a place far off the beaten track where she and Eddie and her two boys could just relax and have fun. But, when the women servants in the household learned that the guests were to be the “divorced” Fishers, they walked out and the men servants walked out with them. They rented another house, on Costa Brava near Bagur, and this time they did not reveal their identities. But, soon, everyone seemed to know who they were. They would flock to gape and glare at them while they were swimming or picnicking. Finally, a complete detachment of Alguaziles (civil guards) were sent out to protect them from the crowds, but instead of keeping back the onlookers, the civil guards mingled with them. The mob’s nearness, their sneers and catcalls, the women, incensed over her bathing suit—a one-piece suit and modest for America, considered revealing and reprehensible for Spain—finally drove them from the beach.

Jamaica would be different, a new start, they had hoped

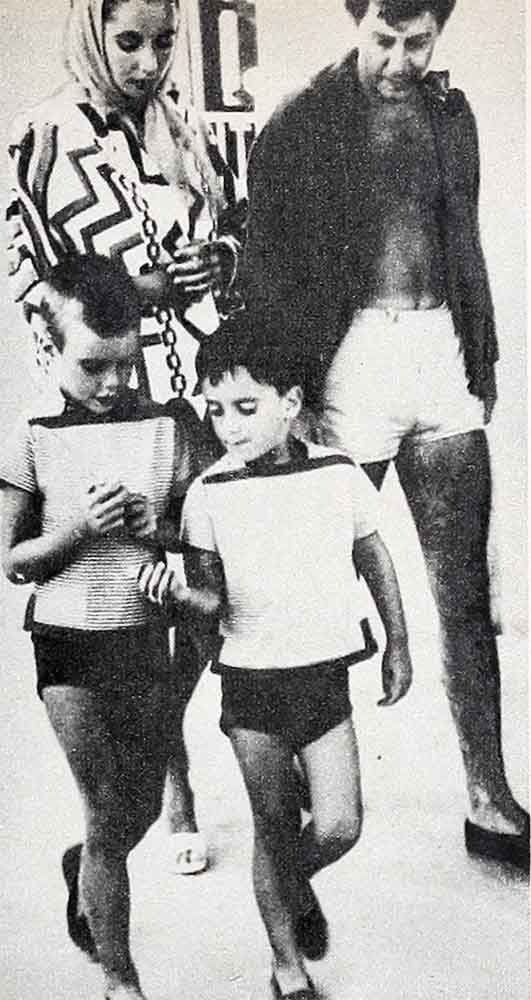

September, 1959. She remembered the look of pain and confusion on the faces of her sons, Michael, 7, and Christopher, 5, when they’d hurried from the beach in Spain to their house, with the shouts and jeers of the crowd only dying away, completely, when Eddie bolted the shutters in their suite. They had the same look a month later, at London Airport, when Eddie and she took off for Paris without them. It wasn’t that they felt they were being left behind, again—it was the reporter who had sneaked over to them and begun firing questions. Michael and Christopher had cringed and were almost in tears by the time she and Eddie rushed over and rescued them.

It was the same confusion and pain she had seen on their faces that day, way back in May, when her secretary, Dick Hanley, brought them to Nice by plane to join Eddie and herself on their honeymoon. As the plane from New York, via Barcelona, taxied toward the hangar, she saw Michael’s excited face pressed against the window and she knew he’d seen her. He smiled and waved and his brother’s face peered over his shoulder. But when Michael, the very first one off, came to the head of the landing ladder, he saw the photographers massed below. He shrank back into the plane, and it was some time before Dick was able to convince him and his brother that they would be safe in going out. Her daughter Lisa’s face was calm and sweet in sleep, when her nurse brought her down to the field, but Michael’s and Christopher’s were covered with pain and confusion.

October, 1959. She remembered their return to the United States. They had looked forward to it and to Eddie’s engagement at the Desert Inn in Las Vegas. . . . And then Eddie started gambling, a little bit, and then more and more. “Same old story,” said the columnist—first Nicky Hilton, then Mike Todd, now . . . Eddie had to lead his own life, she told herself.

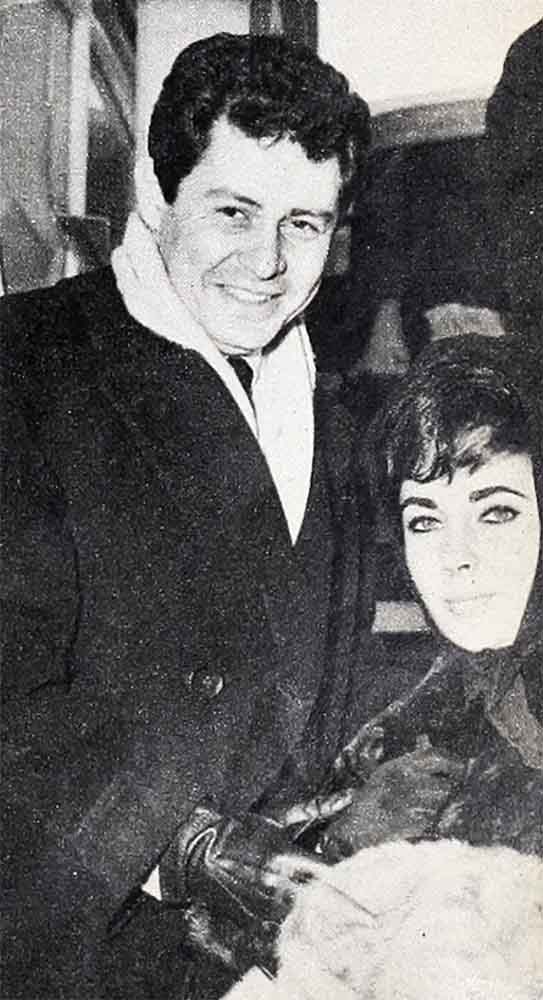

November, 1959. Eddie’s opening night at the Empire Room of the Waldorf Astoria. . . . She remembered, now, not the applauding crowds, not the rave reviews, not the sound of Eddie’s voice, warmer and greater than it had ever been before, but the way the press had distorted and twisted almost everything she had done. People couldn’t believe she was proud of Eddie—and very much in love with him. She had invited seventy friends—many were celebrities—to the opening performance as her guests. The bill, for this, came to $1,500 and the press accused her of “buying” a favorable audience because she thought Eddie sang badly. How could she explain the truth: that she asked them to come because she knew he’d be a sensation? She sat there, calmly, in the Empire Room, that night, wearing Eddie’s favorite diamonds and chinchilla, listening to the crowd call Eddie back for encore after encore. No one knew she was suffering from a high temperature. This night was Eddie’s . . . and only Eddie’s. Nothing must spoil his triumph.

December, 1959. Their first Christmas together and it looked as if she might have to spend it in a hospital. She’d kept her illness from Eddie—muffling a hacking cough—until Thanksgiving Day. She’d prepared dinner, turkey and everything that Eddie liked best, and then, as they sat down, the coughing and the fever suddenly seemed too much. They had to leave the dinner untouched on the table. They took her to the hospital—Harkness Pavillion.

The diagnosis was made—double pneumonia—and Eddie moved into the room next to hers to be close by. The doctors said that hers was one of the worst cases of double pneumonia they’d seen in a long time and that her lungs were almost completely congested. The delay in coming to the hospital, they claimed, made her condition almost critical.

For three weeks, she lay in the hospital bed, and for three weeks, Eddie was with her every minute when he wasn’t on-stage at the Waldorf. He tried to cheer her up—bringing her hot pizza (which she couldn’t manage to eat), arranging for the mink sweater that he’d ordered for their six-months wedding anniversary to be delivered to the hospital, making sure that her children called her every night. She could never get used to hospitals, though she’d been in so many—fifteen different ones altogether—for manipulations, examinations, and then that four-hour fusion operation on her back three years ago, the caesarean during Lisa’s birth and a series of throat operations.

So it was with great relief that, on December 13, Eddie came for her and she walked out of the hospital, wan and weak, leaning on his arm, but out in time for Christmas just the same.

January, 1960. “Liz Taylor is definitely pregnant,” she read in the paper, one day. And another rumor, nicer, perhaps, than the report in a British paper two months after their marriage in June, that she was “expecting in November.”

The latest rumor brought all kinds of scary warnings from her friends, from the press, and from people she’d never even met. “Don’t have another child,” they’d said. “Caesareans are dangerous—to the mother, to the child”—they went on. When she insisted she wasn’t pregnant, they accused her of lying. When she replied it was nobody’s business but hers and Eddie’s if she were pregnant or not, they wrote that she was nasty and uncooperative. In the end, she simply bit her tongue and said nothing.

February, 1960. Funny, but about all this eventful month, she remembered just one thing: her 28th birthday. A crazy day, with sweet, kind, loving Eddie doing everything to make her happy. And a day of memories: They’d talked about her childhood. The first day on the set of “National Velvet.” She was thirteen. Her mother, always a little off-camera, gave hand signals—hand on stomach when her voice got too shrill; hand on heart when she wasn’t showing enough emotion; hands on cheek when she should smile more; hand on neck when she was overacting. . . .

March, 1960. She remembered how horribly March began, with memories of Mike’s death—two years ago—and how beautifully it almost ended. . . . almost. She and Eddie’d been to visit his mother in a Philadelphia hospital, where she was recovering from a heart attack. After they’d left the hospital, she slipped on the pavement and severely cut her leg. The motion picture strike was on; her leg was slow in healing; so it seemed a fine time to take a vacation from everything. She and Eddie flew off to Jamaica in the British West Indies.

On the plane down, Eddie just had one cup of consomme, but she threw caution and diet to the wind. During the five-and-one-half-hour B.O.A.C. Britannia turbojet flight from Idlewild to their destination, she ate almost without stopping and drank glass after glass of what Eddie calls Liz’s soda—champagne over ice.

At Montego Bay, they transferred to a small plane that was to take them to the Hotel Marrakesh at Ocho Rios, Jamaica. At the hotel, they stayed in their own three-room cottage (two bedrooms, a living-room, and a private patio). But it was the bathroom that really delighted her: it had a bath tub eight feet long and six feet wide, with three marble steps going down to it. She took one look at it and cried out, “Oh! Eddie, it’s my own private swimming pool.”

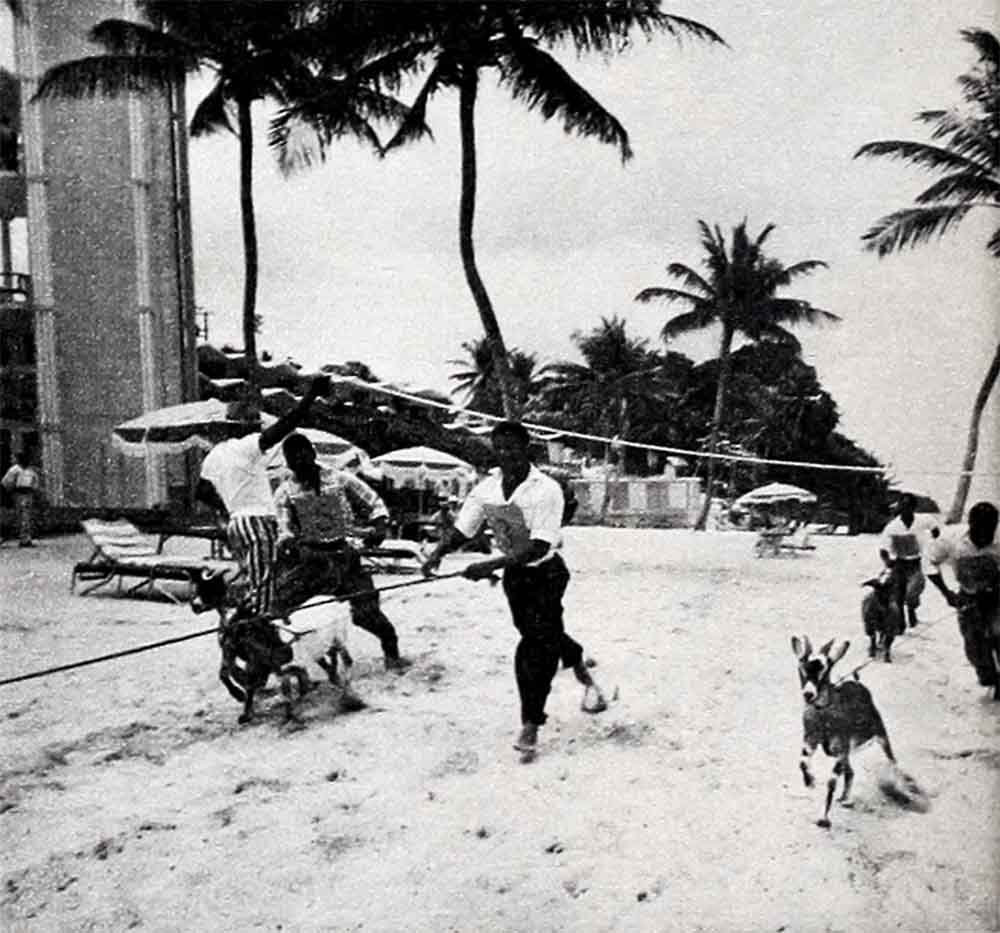

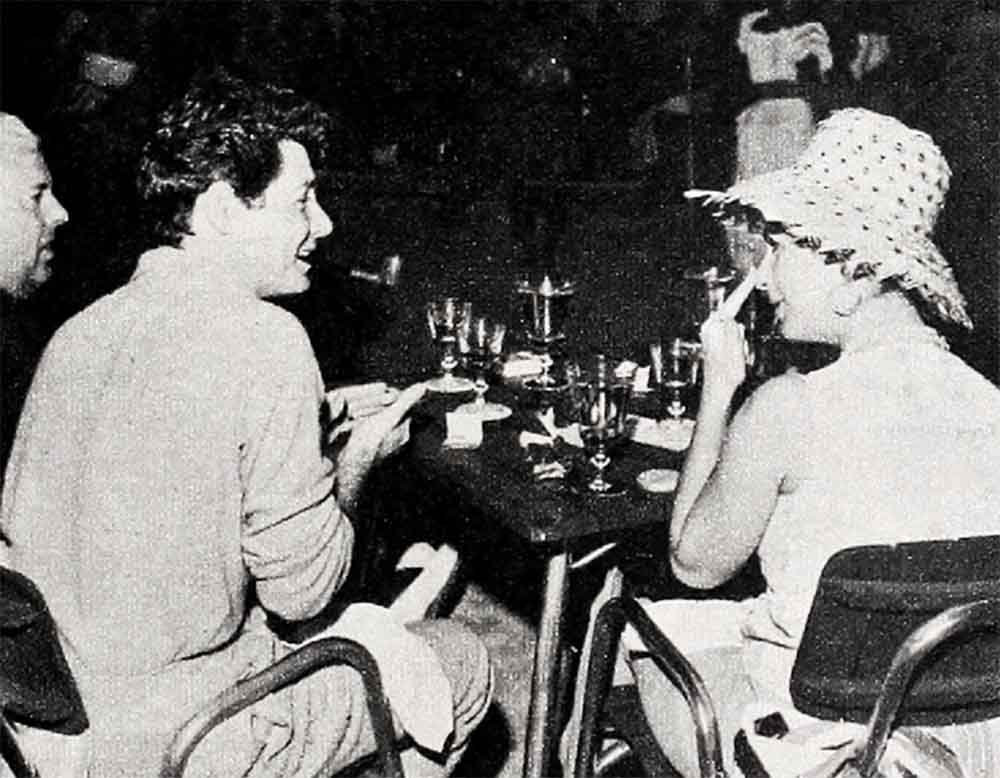

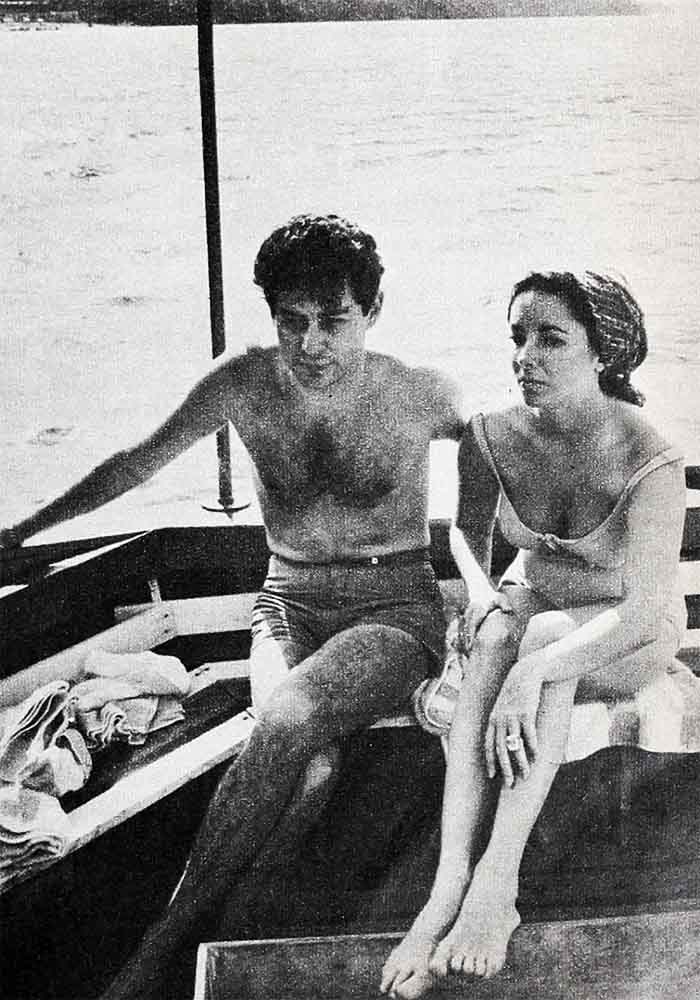

For a while, they were in paradise: no crowds to bother them, no reporters to plague them, no films to make, no records to cut—just privacy. They slept late, ate a combination breakfast-lunch at twelve or one o’clock, and then lazed around the beach or patio all day. At dinnertime, they would attend an outdoor barbecue with the hotel guests or dine alone on their own patio. At night, they’d walk along the beach in the moonlight, or take rides on the bay in glass bottom boats, or visit offbeat native night clubs, or watch goat races on the sand.

Eddie was fascinated by the races, real contests between six goats, each of whom was guided on a leash by a native boy. The guests would bet on each race. She and Eddie never bet on the same goat. She’d get advice on whom to bet from their favorite waiter, dubbed “Benny the Bookmaker” by Eddie. Eddie talked directly to the jockies, offering to split his winnings with them. She’d bet two dollars a race and Eddie would bet ten, and every night she’d win and he’d lose. At the end of their stay in Jamaica, she turned all her winnings over to her adviser, “Benny.”

Each lazy day was followed by a still lazier day. They went shopping for things for the boys and for Lisa. They sneaked in to see “National Velvet” and nobody recognized them. Each evening, they’d call Michael and Christopher in New York. It took a century to get through to them, but it was worth hearing their voices, even when Michael swore that he was eating his vegetables while his nurse insisted that he wasn’t. Late at night, they’d sit on the patio—he’d sip Coke and she’d drink iced champagne—watching the lazy moon overhead and listening to the pleasant beat of the surf close by. They had never been happier.

Then the champagne went flat and the bubbles burst. It all began innocently enough. They’d meant to go shopping, early, but they’d been racing up and down the beach like high-school kids and had forgotten what time it was. Too late, they realized that shops closed at 4:30. Eddie called up one of the stores and asked if they’d stay open a little longer. “Sure,” they said, “be here by six.”

But then other shopkeepers heard that they were coming and they all decided to stay open. Some of the guests heard they were going to the shopping area and they decided to go along. Soon, a whole bunch of cars were following their Cadillac to the stores.

They went, they purchased things, they returned to the hotel, and that should have been that—but it wasn’t. A local newspaper ran a front-page story about “Elizabeth Taylor and her faithful retinue.” That was just the beginning. Next came a vicious editorial which matched in untruth and bad taste anything that had ever been written against them. all the old charges were made . . . and some new ones as well: it poked fun at her “broken leg” and pointed out she’d had a miraculous cure (it didn’t matter that she’d never claimed her leg had been broken); it accused her of “buying” an appreciative audience for Eddie’s Waldorf comeback; it said she maneuvered a part in “Butterfield 8” for him; it unloosed a flood of innuendo and criticism.

Paradise wasn’t the same. Not so long afterward, they left Jamaica and flew back to New York. How much more could Liz take?

April, 1960. Early in April and the night of the Academy awards. She tried not to let her hopes rise. When people told her that George Sidney had said, “Elizabeth Taylor will win an Academy Award for her performance in ‘Suddenly Last Summer,’ ” or that the conservative Herald Tribune had stated, “. . . if there were ever any doubts about the ability of Miss Taylor to express complex and devious emotions, to deliver a flexible and deep performance, this film ought to remove them,” she smiled and changed the subject. She remembered the year before, her “Cat on a Hot Tin Roof” nomination, and the public opinion which had turned against her after Eddie gave up Debbie. So she smiled and thanked people for their good wishes and tried not to dream of the Awards.

Only Photoplay’s Sidney Skolsky revealed her true feelings when he recalled how she’d told a London newspaperman earlier in the year: “My ambition is to win an Oscar before I retire. Only then will I be really content to settle down to a full domestic life.”

She did not admit this to herself, again, as at the Pantages Theater, on the night of the presentation, she sat next to Eddie, in the midst of a small group of friends, and listened to the presentations being made. Her smile was easy and natural, as if she were home, alone, with Eddie and their kids. Then the moment came, the card was read. and the name rang out: “Simone Signoret.”

She did not stop smiling for a moment; she clapped her hands with the others, and she did not believe it when someone, sitting close by to her, told the press he had heard her whisper, “Oh, no.” . . . But she could not be sure.

Matilda, Elizabeth Taylor’s pet monkey, jumped up on the desk and pressed her nose against her mistress’s cheek, and Liz had to laugh. The calendar dropped from her hand. At that second, the door opened and Eddie came in, his arms piled high with fancily-tied packages. It took a few minutes for him to pile the gifts on the couch and when he turned toward her, she was smiling, and the look in his eyes told her that, for the moment, everything was all right and she forgot the heartbreak of the past year, and the jinx that seemed to follow her.

THE END

LIZ STARS IN “SUDDENLY, LAST SUMMER” FOR COL. SHE’LL BE SEEN WITH EDDIE IN M-G-M’S “BUTTERFIELD 8.” EDDIE RECORDS FOR RAMROD.

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE JULY 1960

AUDIO BOOK