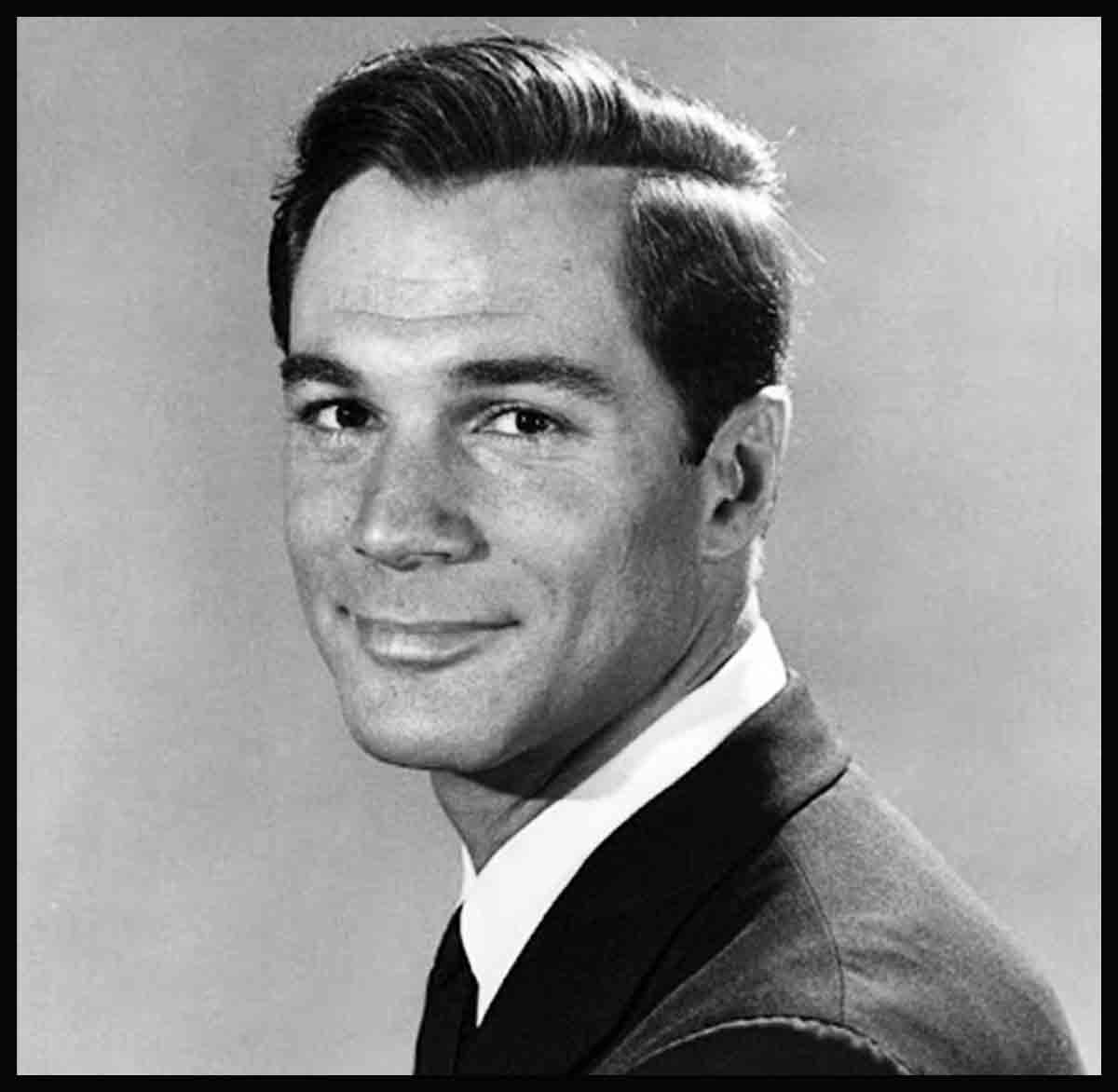

“Get Me My Pants And A Taxi”—George Maharis

An exclusive interview with George Maharis

The patient in Room 400 of St. John’s Hospital, Santa Monica, California, had made a mess of the place. Neither Dr. Kildare nor Dr. Casey would have tolerated the conditions for an instant. But George Maharis didn’t care—to him Room 400 was home. The news of his stay there had been smothered with a cloak of uncertainty during the past weeks. All people knew was that the co-star of “Route 66” had been rushed to the hospital with what was reported to be hepatitis. But those close to George knew more, and they had good reason to be worried. They knew that he really had hepatitis—the infectious variety—and that recovery was long, dangerous and very unpredictable. His friends tried to ease their own fears by saying, “Oh, George is strong. Nothing can stop him. He can fight it.

When I thought I was coming down with the flu, I yelled—“Call Dr. Kildare!” When I found out I had hepatitis, I hollered—“Get Ben Casey!” Then when I heard Marty Milner was taking over “Route 66,” I screamed—it, he’s indestructible—he’s a real tiger!”

But it was only the prestige of Photoplay . . . and a solemn promise to keep our visit short and to put on a mask and a hospital gown . . . that got us in at all.

A radio and record player were piled precariously on one side of the bed. A bed table suspended over his body was stacked with letter-writing folders, magazines, books and scripts.

On the table beside him was a small stockyard of pill vials, three jars full of mysterious liquids and a half-gallon jug of what I later learned was carrot juice.

As I came into the room, the record player was blaring a hot trumpet.

“A memory to my friends . . .”

I said, “What happened?”

He said, “Who knows? Sit down. The tranquilizer’s wearing off and I’m so bored I’m ready to climb the wall of this soundproof cell.” He added sadly, “Can you imagine having to kill three weeks in a hospital just because I have a hot liver?

“Yep, hepatitis. The doc said three weeks in here. I said, ‘But I’ve got a lot of things to do, I can’t spend all that time on my back.’ I was told, quietly but firmly, that unless I did my time and took the cure now, in a year I might be just a memory to my friends.

“You know what I am in this place? I’m an organism in trouble . . . a biological malfunction . . . a mass of crazy mixed-up chemicals that have to be straightened out. The real me is lying on that clipboard down at the foot of the bed, all graphed out in thermal geography—the mountains are my crises and the valleys and plateaus are my normalcies.”

Maharis chuckled. “Funny,” he said with a smile, “for some thirty years I’ve been threatening life. I’m going to get this and that and nothing can stop me. Well, I guess life took just so much of that nonsense and it threatened me back.

“So I’m here.” (He took a swig of carrot juice.) “Three weeks here have changed me in a lot of ways,” he said.

“They’d tell me everything was going to be all right. I guess I’m like everyone else. They’re trying to spare me. I’d think. It’s a lot more serious than they’ll admit, but they don’t want to worry me. Man, how that kind of jazz tears through you! I was afraid, really afraid, for the first time in my life.”

He thought about that. Then added, “It takes time, but my preoccupation with death finally wore off. I started to do some reading and I ran across a story about me written from an interview I’d had months ago. I was quoted as saying that despite every wonderful thing that had happened to me in the past couple of years, I still felt rejected—that I was being taken as a kind of image and not as a human being.”

Maharis took a big breath. “Man, three weeks in a hospital changed me on that, but quick. What I mean is, I was kidding just now when I said I was an organism in trouble to the people here at the hospital. In this hospital I am a human being. And I’ve decided that a hospital has the greatest basis for acceptance that I know.

“If you’re all right, you can’t get in. Think about that. If you’re in good shape, get lost.

“But if you’re in trouble, if there’s something wrong with you, if you’re frightened or worried, you’re welcomed by people whose whole lives are magnificent devotions to the relief of your fears, your worries and your ailments. All they care about is making you well!

“How different from life outside.

“Wouldn’t it be kind of great if people felt that way about each other? I mean your best friends are people who need you! Not because they’ve got money or influence or good looks or great wit. You become close to people who need help. What a switch that is!”

Maharis looked out the open door (through a narrow channel between the record player and the speaker box), at the nurses and doctors who passed briskly.

“Hospital,” he said softly. “Used to be nothing to me but the name of a place you tried to stay out of. Means more to me than that now. All these people. Doctors with good, steady eyes and minds to match. Nice, crisp, happy-eyed nurses and the wonderful rustles of cleanliness about them.”

He shook his head. “What a place,” he said. “What a wonderful place.”

Although George had given the impression that he was eager to talk, it was evident he was avoiding one aspect of his stay in the hospital. According to the rumors that had been running around Hollywood, his particular kind of liver ailment was the most feared of all—especially by actors. At least six well-known stars have had their careers cut short by similar liver attacks.

After hearing that a number of “reliable sources” had put him on the doomed list, Maharis shrug-smiled it off with. “I don’t think the sources should be considered reliable anymore.”

“Look.” he said. “I’ll tell you the truth. Yes, I knew about the others. They were the first ones to enter my mind when I was told what I had. I got the fright. My heart shrank and I felt like an ice cube. But those were only bad moments. As long as I was alive I had a chance. As long as there was medicine and doctors and nurses—hell, when you have all that going for you, you suddenly get a chest full of hope.

“One doctor told me the worst thing that cuts down a man’s chances when he’s seriously ill is the uncontrollable anxiety the affliction generates in his mind. It’s a little like standing on the edge of a high building. You get the urge to jump, but you resist it. When you get hit like I was, you get the urge to despair. I just had to learn how to resist it. I’d wake up in cold sweats with the sheets balled up in my fists. I’d close my eyes in the dark, and in the quiet of this room I’d try to drive the demons of desperation out of my apprehensive mind. Not easy!

“I spoke to God. It was a time in my life when it was the sensible thing to do. I don’t pray a lot because I think you must learn to help yourself before you ask God for help. But I needed Him and He was there.

“I leave the hospital in three days. They’re taking me in a car to the airport, putting me on a plane for Connecticut. When we land, I’ll be taken in another car, helped into the house where I’ll live and fight with boredom for at least a week. No exertion. Then in the following three weeks I’ll get to walk again. Little by little.

“It’s got to be that way. Because if that schedule isn’t followed, I’ll have a relapse. And if I have a relapse, one of two things will happen.

“I’ll die.

“Or I’ll be tied to a bed for at least a year.”

Maharis stared at the sheets and took I another gulp of carrot juice.

Then he laughed.

“Pity the weak? No!”

“Don’t worry,” he grinned. “I won’t have a relapse. I know a lot more now than I did three weeks ago. Or ever. . . . When I was a kid I was small physically. But God was kind then, too, so I was strong. Strength was important to me, physical strength. It made up for a lot of things. So because I was small, I took care of my body and I stayed strong.

“I used to feel sorry for people who were weak. But not really. My feeling was the pity of superiority. I was strong, someone else was weak. That’s tough. I was always generous with my sympathy . . . my superiority.

“It took twenty days in this bed to know how it feels to be weak. Really weak—helpless. To need strength so badly that your life depends on it.

“I learned something else.

“In a way, the weak have a peculiar strength that in some respects is greater than muscle. They have the courage to bear weakness, to live with it, to rise above it. It’s a test to which the strong are rarely put. And from where I’m lying, I’m not so sure that the strong could pass the exam.

“I’ll get my strength back. But I’ll know, I’ll always know, that once I was weak. I’ll never forget it.”

It was time for me to go.

I wished George well and told him I’d let people know he was on the way back.

The nurse came in, looked at me sternly and then at her watch. I got the clue and left.

I stopped outside the door for a minute to check the which-way to the elevator.

Suddenly George’s voice came through the paneling.

I didn’t hear all the words. But what I did hear . . .

“Nurse,” he was saying, “you’re a wonderful, beautiful woman and I respect you deeply—but I’ll be damned if I’m going to use that bedpan!”

George Maharis was on the way back—for sure.

THE END

—BY TONY WALL

George stars on “Route 66”, CBS-TV, on Fri. 8:30-9:30 P.M. EDT. His first record album is “George Maharis Sings” for Epic.

It is a quote.PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE AUGUST 1962