How Would You Like It If Frank Sinatra Were Your Father?

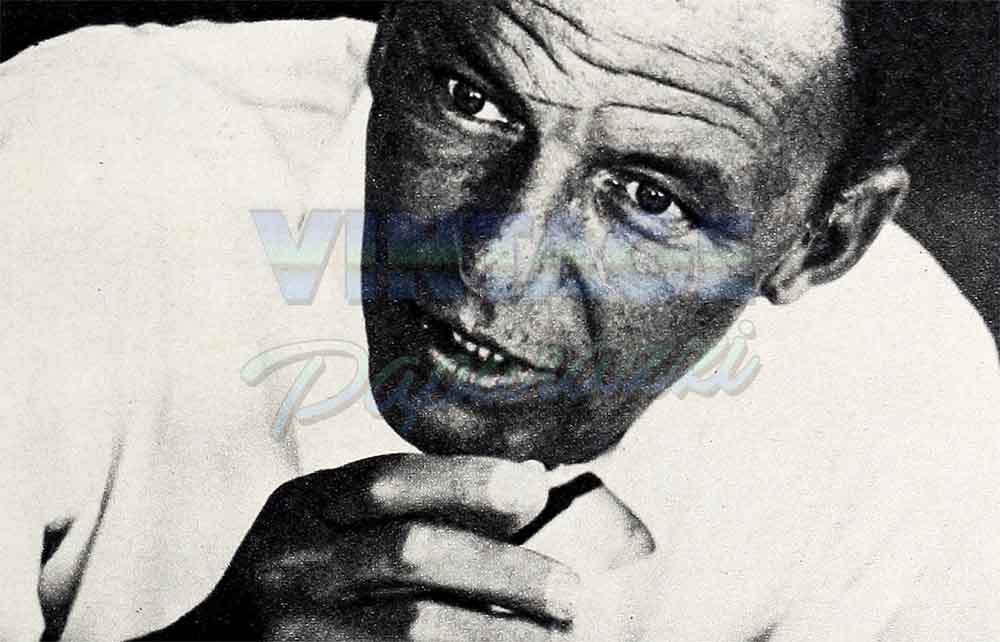

He stood there, tall, lanky, in the middle of a large, lavishly furnished room that was boisterous with joy. More than a hundred persons milled about talking, laughing, shaking hands.

It was a wedding reception in the Emerald Room of the Sands Hotel in Las Vegas, and the small girl who was the bride flitted from one guest to another like a happy white butterfly. A group of men stood around her young husband, wishing him well.

But the awkward young man, a teenager, stood alone. Many of the guests weren’t quite sure who he was. The young man watched the bride with a slight smile and from time to time she looked his way and winked at him.

Suddenly an older man walked up to the teenager and said, “Hi, I’m Joe Crowley from the ‘Los Angeles Mirror.’ You’re the only person in the room who looks worried. Are you an ex-suitor of the bride?”

AUDIO BOOK

The young man laughed sheepishly and shook his head. “No,” he said, “I’m not worried, I’m nervous. Do you realize that in a year I might be an uncle?”

The newsman seemed confused. “I don’t get it,” he said. He thought for a moment. “Say, I didn’t get your name.”

The teenager’s smile disappeared. His gaze came slowly back to the reporter’s inquisitive eyes.

“My name,” he said softly. “is Frank Sinatra.” And added, “Junior.”

“Well, well,” said the reporter, “the great man’s son, eh? Did you ever dream your sister Nancy would marry Tommy Sands? And bring another singer into the family?”

“We weren’t sure,” replied Sinatra, Jr. “We only hoped that—”

“The great man’s son,” the reporter said again, interrupting. Now he stared at young Sinatra. “Say, you’ve certainly got a lot to live up to. That dad of yours never missed the action, not if he knew where it was—if you know what I mean.” The last was accompanied by a sly wink.

Young Sinatra froze. He stared coldly back at the writer.

“I know what you mean,” he said. “Now would you excuse me? I have something I’d like to discuss with my sister.” He turned and left.

It was the first time Frank Sinatra, Jr. had ever been hit with his father’s reputation in public. It wasn’t the last. But today, two years later, he is almost used to it. Almost—because there is more to being his father’s son than he expected.

Not long ago, in a talk with young Frank, we discovered that at eighteen the son of one of the most popular men in the world doesn’t let his legacy bother him as much as it once did. But there was a time when it troubled him plenty.

The early years for Junior were deceptively easy. He enjoyed his inheritance. Being the son of Frank Sinatra immediately catapulted him to the top of any group outside his family. Even the kids he played with as a child realized that there was something special about Sinatra, Jr. Not that he was any different from the rest, really. It was just that—after all—his name was Frank Sinatra.

As young Sinatra grew older and entered his teens, however, he began to notice that everything was fine until he mentioned his name. Then things changed.

“I was very content to be just one of the group,” Frank, Jr. recalled. “I know now that I was trying to be myself. But things never stayed that way. The instant my name was out, everyone’s attitude changed. No one seemed to care about me anymore. They were too busy asking questions about my dad. And they’d stare at me. Trying to see the resemblance, I guess.”

By the time he was sixteen, he could predict—with simple weariness—exactly what a stranger would do and say the moment he realized he was talking to the son of Frank Sinatra, Sr.

The questions and comments conformed to an inevitable pattern . . . “Frank Sinatra’s son? . . . Well, you’ve certainly got a man to live up to . . . You really don’t look like your dad . . . Say, do you remember that time your father was involved with . . . now tell me what really happened?”

In fact, Frankie knew little about his father’s private life. For, in contrast to the millions of words that have been written about Sinatra’s “personal affairs,” he was and is, without question, one of the best fathers in Hollywood. As Nancy, Jr. once put it, “My father may have left home, but he never left his family.”

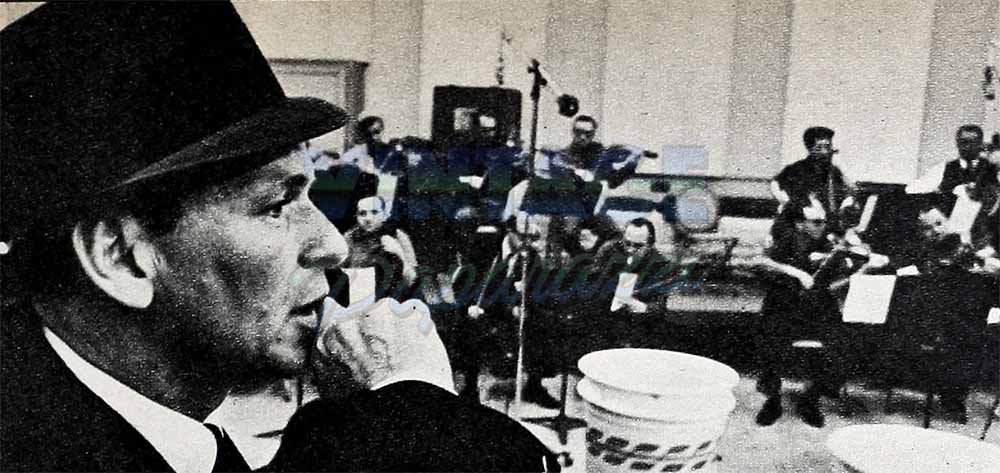

The reason for Sinatra’s utter devotion is best expressed in his own words. “When a man creates something he should take care of it. I created my family.”

But for Sinatra, Jr., the right thing to do didn’t come that easy. His situation was without precedent. The sons of Bing Crosby at least had each other. Young Sinatra had no one.

“Shortly after my sixteenth birthday,” he explains, “I realized that being Frank Sinatra, Jr. was something I’d have to understand. I couldn’t just accept it and carry the name. I had to decide what it was going to my whole life.”

But for all his youthful good intentions, those closest to Frank, Jr. say that his fifteenth and sixteenth year were the worst.

“It got so bad,” says a buddy, “that it began to show on him. I mean, you could see the little crisis coming in the expression on his face.

“We’d be in a group and a new guy would join us. Let’s say I’d introduce myself to him by saying my name. So would the other guys.

“But, man, was it tough on Frankie! It seemed as though he was dreading the moment he’d have to say, ‘And I’m Frank Sinatra, Junior.’ You know what I mean. It wasn’t that he didn’t like his name. It was what that name did to a stranger. I guess Frankie thought that every time he mentioned who he was, he lost his own identity. His real self just disappeared in the shadow of his great father.

“It got so bad there for a while that when someone would ask him his name he’d hesitate, clam up. And just before the big change came over him, he began to stammer when he talked. He seemed edgy and nervous most of the time.

“I asked him about it one day. Why he was beginning to mumble. Because he really wasn’t that type of guy. He is bright, alert. I wish I had his brain. He could be anything he wants to be.

“Anyhow, when I asked him about the stammering, he just asked me a question. I’ll never forget it, because it really brought home to me what his problem was.

“He asked, ‘Tell me, Eddie, how would you act if someone asked your name and you’d say, ‘My name is Frank Sinatra.’

“I’ll never forget it, because though he was the son of one of the most popular men in the world—his words were drenched in loneliness.”

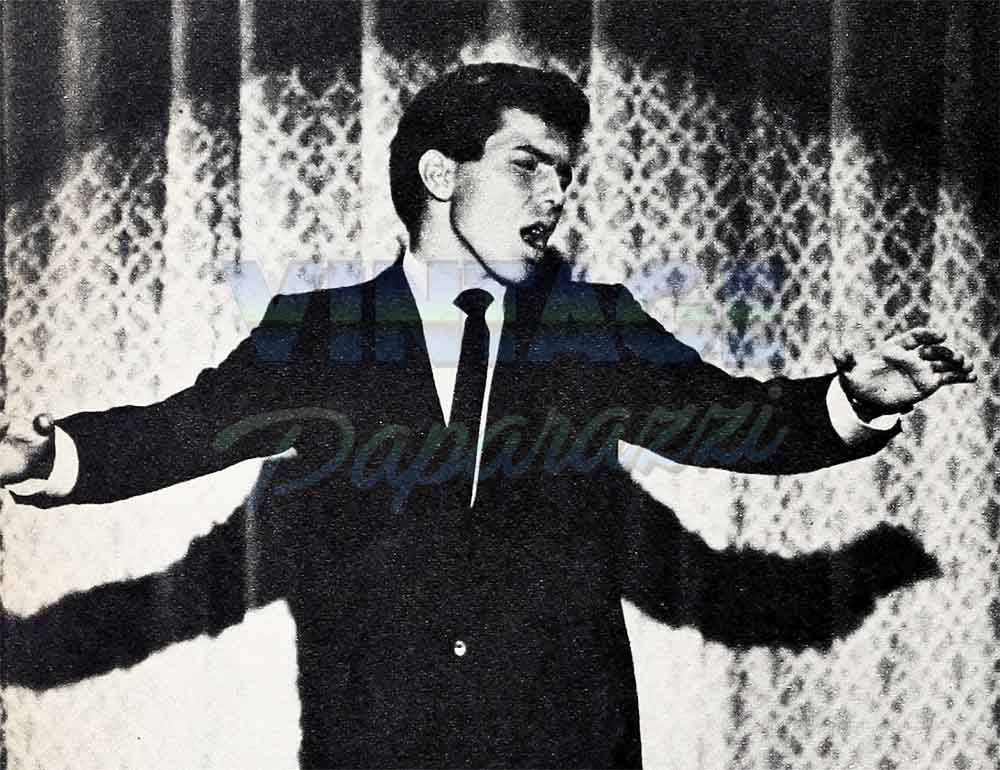

In the last two years, however, young Sinatra has learned to accept his lot, though there are times when the old reluctance creeps back. Not long ago Frankie, who’d like very much to succeed on his own as a singer, visited Disneyland where the Elliott Brothers were entertaining hundreds of teenagers. He listened to them for a while and then the urge became irresistible.

“I said to myself,” Frankie explained, “that I was going to have to go the route on my own. I was going to have to take my chances alongside every other guy my i age who wanted to become a singer.

“So I just sauntered over to one of the bandleaders and told him I’d like to try a song or two with the group. He looked at me oddly. I guess he was amused.

“He asked me if I had any background. I said I had lots of background. Then he wanted to know what made me think I could sing.

“I told him that I wouldn’t be making the request if I thought I was going to make a fool of myself or the group.

“Well . . .” he hesitated, but finally he said okay.

“It was pretty informal all the way, but I got through the song fine.”

Actually, Frankie did well and got a tremendous hand when he finished.

The leader said, “Hey, what’s your name?”

Frankie laughed and started to say it. But he didn’t have to. One of the musicians, an old Tommy Dorsey bandsman. hollered out, “That’s Frank Sinatra, Jr.!”

“It was great,” he said. “I had sweated out the whole bit on my own, just like anyone else. I didn’t care then that they knew who I was. The important thing was they didn’t know until I finished.”

The bandleader later called Frankie back for an all-Dorsey show, a week later. Young Sinatra couldn’t have been more pleased. He’d had his professional baptism.

Then he appeared on a couple of Los Angeles TV shows and finally a star spot with Jack Benny, who assured all concerned that he was using Junior for his talent and not for his name.

Sinatra, Sr., on learning of the turn of events, grinned like a kid. “I always said that son of mine was full of surprises.” Frankie’s mother is not convinced that show business is the best bet for him.

“She is a wonderful mother to us,” Frankie explains. “But she’s seen an awful lot of the heartache that goes with being an entertainer.

“Still, I think I’m old enough now to take a few lumps, as Dad says. I understand now that most disappointments are just a part of your education for life.” We asked Frankie why he hadn’t changed his name. Wouldn’t it have been easier.

“No, I thought about that,” he said. “But how long could I go on without facing it? That would be worse.”

He laughed. “Can you imagine how the billing would look if I look a name like Al Stanley and underneath, in large print, it said, ‘Son of Frank Sinatra?’

“There were other reasons. I’m proud of my name. I’m proud of my father. People will never know what a wonderful parent he’s been to us. So I’m proud to be Frank Sinatra, Jr. I want people to know that. My father gave me my name. And the best way I know of to show my gratitude is to earn the right to use it and, maybe, someday do enough good things to make him proud of me.

“It’s something every son should do for his father. I like it that way.”

He thought for a moment, “That’s why I’m not afraid anymore,” he said. “I’ve got the whole world ahead of me.”

—ALAN SOMERS

AUDIO BOOK

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE APRIL 1963