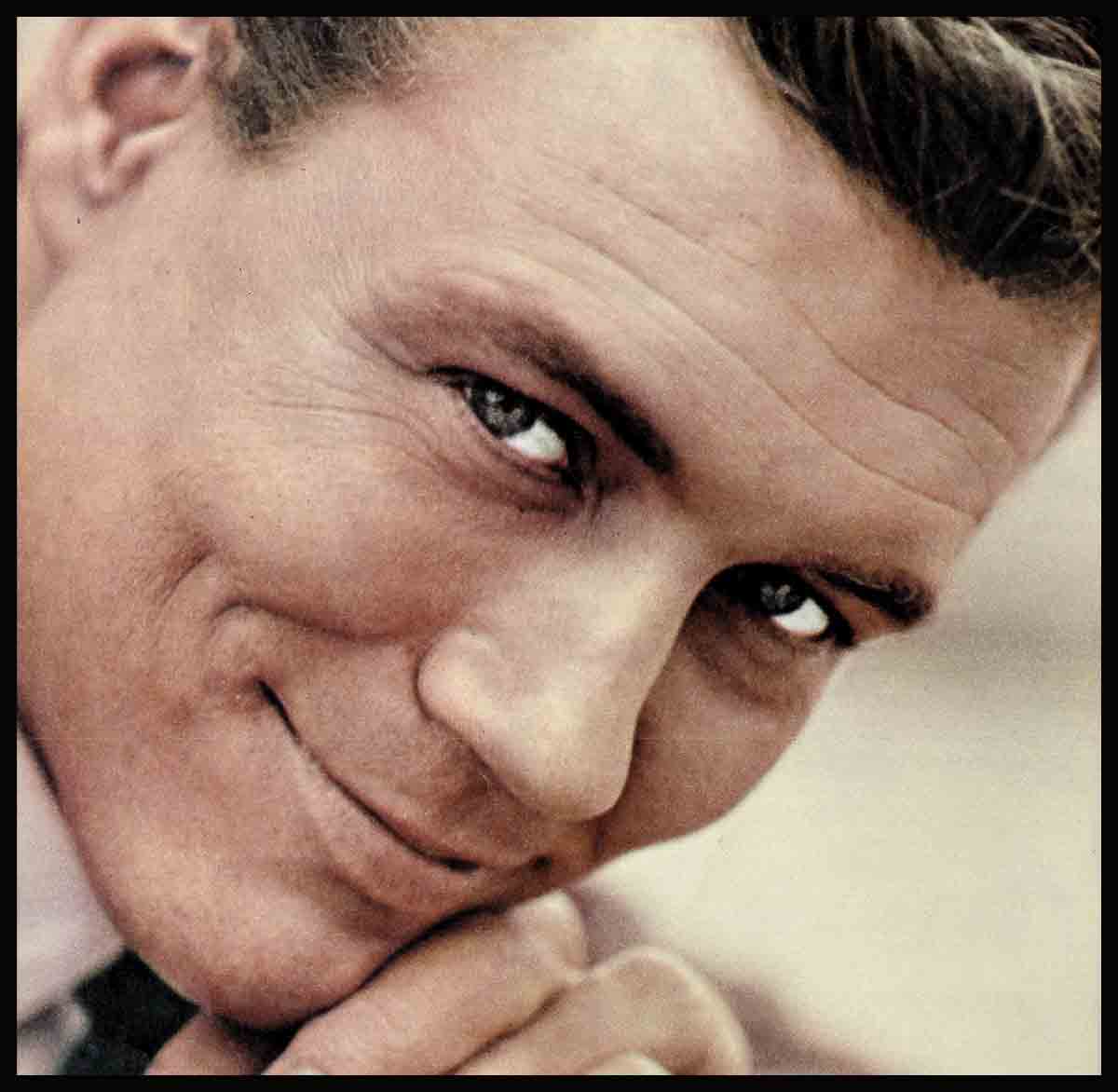

This Is A Secret That Can Only Be Whispered—Roger Smith

Roger Smith has lied, carried on, deceived his wife and confused his children almost every day of his working life. And they know it.

“Roger, it’s seven-fifteen,” Vici will say, as soon as she wakes up in the morning, nudging her sleeping spouse. And still sound asleep, with his eyes wide open, he’ll make up a whopper like, “I forgot to tell you. I don’t have to go to the studio today.”

From long experience, Vici gets up without another word, to telephone the studio to check this wild statement. For she knows that if she asks Roger again, she will only get the same answer. And almost always, the studio reports: “You’re darned right he’s expected. He’s in every scene. Get him here!”

Meanwhile, daughter Tracy, aged 3, and son Jody, aged 2, stare at Daddy under the covers until Mommy returns and routs him out of bed. Not until he is bathed, shaved and reasonably drenched in coffee does he remember any of his wild morning deceptions. But once awakened fully at 7:31, he is a live wire and ready for work. Work is at Warner Brothers studio.

Five mornings a week, at 7:45, with the help of his wife, two children and the neighborhood dogs, Roger Smith drives through Warner Brothers’ studio gate, parks his car, takes out his lunch pail and reports to the set of “77 Sunset Strip,” where he turns into detective Jeff Spencer.

Because he’s a chronic “forgetter” and “a misplacer,” his wife has printed on his lunch pail, “This kit belongs to Roger Smith.” As a result, since last August, he hasn’t lost a single pail, although people from all over the set are constantly tracking him down with, “This your lunchbox, Roger?”

His lunch from home is always the same. The contents of the lunch pail correctly calorie-counted are one sandwich, one apple, one banana and one cookie. It is his wife’s way of keeping him out of the studio dining room, where, if he does go on occasion, he invariably overeats, which he doesn’t want to do.

He should, but he doesn’t watch his diet. On the evenings they go out to dinner, Roger will invariably head for a Mexican restaurant, stuff himself with tamales and then go home to be sick.

“Why do you do it, Roger?” Vici would question. “You know it always makes you sick.”

But the very next week, there is Roger, sick all over again, on tamales. And the worst of it is, it goes on and on. He can’t understand it himself.

On the set, if a problem comes up, he simply falls asleep. He can sleep in his chair for one or two hours while all around him is clamor, din and confusion. All his life, he’s retreated into sleep the minute unpleasantness comes up. It saves him, he claims, a lot of wear and tear on the nerves. When free from work and home fixing problems—like how to build an addition on to the addition on to the garage—he can and does sleep fourteen to sixteen hours at a stretch. He’s that easy and relaxed, although he can be lulled into well-being with Vici’s words concerning family arguments.

He doesn’t feel married

“Why quarrel?” she says. “We know we’re not going to separate, so why make ourselves miserable?”

He’s got himself one girl in a million and he knows it. It’s fantastic, but for that matter, so is his marriage. But there are times, he confesses, he feels as if he were living in—well, not sin exactly—but a sort of premarital, romantic glow. He’s that crazy about the wife who so wisely has remained a sort of unfathomable enigma to her husband.

“I don’t feel I know Vici,” he says. “I don’t feel married, because I can’t out-guess her. She keeps me guessing. I learn new things about her every day. All the other girls I dated, before Vici, I knew like a book inside a few weeks. We’ve been married four years now and I’m still learning new things about my wife.”

Nevertheless, he can be a frustrating husband at times. He’ll never dish-dry and runs away from the vacuum-running. And while he’ll uncomplainingly put up with his wife’s cold feet, he has the nasty habit of falling asleep right in the midst of a good soul-satisfying argument—and any wife knows nothing can be more upsetting.

In the beginning, the Smiths were definitely disorganized—financially. With both Roger and Vici progressing in their careers, they gave no thought for tomorrow. If Roger decided he needed a new power-saw, he’d buy one, regardless of cost. Or, if they wanted new luggage for the car, or maybe a new car, they got it.

They learned better, in time. Today, they operate under a business manager and, like most careful young couples, they stick to their budget.

He’s romantic and quite a philosopher on love. He believes a man should never try to reason out a woman. “No man ever knows why a woman says this or that,” he insists. “Women reason on an emotional basis rather than intellectual.”

Vici, quietly listening to this dissertation, permits the remark to pass by without comment.

“Men are attracted visually to women,” he goes on, “but it’s the opposite with women. Men are usually drawn to beauty in the opposite sex. Women aren’t. Not always. Men admire a voluptuous woman. Most women are repelled by a man with over-developed muscles that make him seem a modern Goliath.

“Like any male animal, men are stimulated by sounds and scents. They thrill to the soft, musical voice of a woman. And when she cunningly uses perfume, a man thinks to himself—she’s trying to attract me.”

“Is that why you never buy me any?” Vici interrupts.

He ignores her. “Now take another sound—music. Music is a woman’s weapon,” he continues. “When she plans to attract a man, a woman turns on soft, sweet music and a man, who sees through her, thinks to himself—she’s trying to please me.”

“Is that why you run from the house every time I play a violin concerto recording?” Vici innocently demands, hiding her smile.

He eventually gives up.

He had trouble with women

No one can ever say that mild-mannered, gentlemanly Roger, would argue with a lady! Although he insists, despite his appealing six-feet-two-inches, blue-green eyes and handsome young years (he’s 27 now), that he has always had trouble with women.

In fact, at the time he met Vici, he was having girl problems all over the place. One girl, in particular, had stood him up and Roger was burning. “Why don’t you ask Vici Shaw for a date just to get even?” a friend suggested. Roger had seen her. A green-eyed beauty with an upturned nose, who came from Australia. To Roger, who’d been impressed with her performance in “The Eddie Duchin Story,” the suggestion was comparable to asking out Garbo.

But, finally, he screwed up his courage, took her to Disneyland (“It cost me $42,” he moans), and what happened? She trapped him.

At no time did he ask Vici to marry him. She asked him. Twice, too, before she got him. The first time that she happened to say, “When we get married,” Roger said, “Now, hold on there. We’re not getting married.” The second time Vici brought up the subject, he came back with a snappy, “Now, just a minute.”

This didn’t bother Vici in the least. Whether lovable old “Roge” acknowledged it or not, she knew they loved each other, had been in love for weeks and they were getting married.

“My reluctance was due to the fact I had no money saved and was making little,” he admits. “But, frankly, I was crazy about the idea.”

The things that happened at their wedding reception should have tipped off Roger to his life ahead.

Their crises go all the way back to the wedding. Without a hitch they got through the ceremony, but disaster struck at the reception at a friend’s home. They were all but ready to depart for their honeymoon when Vici, changing her gown upstairs, made a discovery.

She had forgotten her strapless bra. She’d packed them all and the luggage was outside in the car. And, very clearly, she made it understood that under no circumstances was she going anywhere with anybody minus it.

A woman friend was dispatched to fetch one from the luggage. But along the way, the friend stopped to chat with first one group and then another, and the time dragged on while Vici grew more and more restless.

“Have a glass of champagne while you’re waiting,” a friend urged, but Vici, who seldom drinks, shook her head.

“Well, a little,” the friend urged again, “you’re getting nervous.”

So Vici sipped some champagne. The friend returned; Vici had finished dressing in her going-away outfit and then proceeded to descend the stars, when, with a sudden whoop, she decided to toss the bouquet—and tossed it backwards, knocking off the hat and eyeglasses of the startled usher.

The bouquet was retrieved and retossed by the blushing bride in the right direction, although slightly off center, and the Smiths drove off to their tiny apartment with its one chair, one bed, one stove and to, what Roger calls today, “perpetual crises.”

His silly superstitions

Is he superstitious about all this? He says no, he’s given up superstitions, since he feels he can no longer cope with the consequences.

He used to be superstitious. In fact, when he played football for Hollywood School in Nogales, New Mexico, he drove everyone crazy on the team. Not that he wasn’t a good athlete and a we g player. He was, but somewhere he picked up this irrepressible habit: Before making a pass, for luck, he’d turn the ball over twice in his hands. The team nearly went crazy waiting for him.

And when he played baseball, he simply had to touch first base before going into action. Let the umpire scream and the pitcher howl, old Roge would have to touch the base first.

“It was all,” he shakes his head and smiles a sheepish grin, “just one of those silly superstitions I’d been seized with and could do nothing about.” But it’s all part of the past—his superstitions—he explains seriously, today, while knocking on the wood of his guitar for luck!

It was his guitar that brought him all his good fortune. He took it up at the University of Arizona and strummed and sang so well, that he won first place on “The Horace Heidt Show” and the “Ted Mack Original Amateur Hour.” His guitar brought him good luck in Hawaii when, as a member of the Naval R.O.T.C., he gave performances in little clubs when he was on leave—along with another lad named Bob Shayne, now with the Kingston Trio.

“Look,” a man approached him and said, one evening, after his performance, “I don’t often say this, but with your looks and talent, kid, you should try Hollywood.”

The man was Jimmy Cagney and, three months after his discharge, Roger followed his advice about Hollywood.

Vici has the answer

But he’s never played the guitar in a film, although he estimates that he, along with Efrem Zimbalist, average about 30 full-length movies a year—a tough working schedule.

“Once he gets out of bed,” laughs Vici, “he’s a hard worker.”

Which is true. He seldom works for less than ten to twelve hours daily, and after that, and on weekends, he finds he can never turn down a request from a fan or for a public appearance.

He can’t say no. He knows how he’d have felt, as a kid growing up in Southgate, California, if one of his movie idols had given him an autograph or made a visit to his town. And so he feels deeply about his fans.

He feels deeply about intolerance, too. “Racial intolerance,” he says, “is instinctively planted in the minds of children even before birth.” And, undoubtedly, he is recalling prejudice he found when he moved, at twelve years of age, to Nogales, New Mexico, and found himself the only “blond-haired” kid in the school.

“Intolerance,” he’ll explain seriously, losing, for a rare moment, his easygoing manner, “is passed along through generation to generation and can only be eliminated when people cease passing such ideas mentally to each new generation.”

And Vici will say, at this point: “What you and I need, Roger, is more children. I keep saying it over and over.”

And she means it. She wants no part of the actress-star bit. It’s a bore. She wants only to be Mr. Smith’s wife. She wants only the demands of her spouse, as he suddenly shouts downstairs, “I haven’t any clean shirts”—“Well, why in heaven’s name do you hang up your soiled shirts among the clean ones? Who knows they’re there?” she shouts back.

And he’ll smile as she goes looking for a clean one for him and show her, later that day when he returns from work, that he appreciates her, by having her favorite snapshot, the one he took of her and the kids, enlarged as a surprise.

And he won’t stop off, that evening, at the hardware store and get lost among the household repair gadgets, but drive directly home to their nice-middle-class neighborhood. And, after parking the car in the garage, he may stop to admire and inspect his own landscaping around their house, then dash inside, calling, “Vici?”

And she’ll come running down the steps to meet him and he’ll say, “No bitters in the meatloaf, tonight?” And she’ll shake her head, No.

“No ice cakes with sour cream?” he’ll tease. And she’ll shake her head, No. And then he shuts the door and softly whispers, “I love you, Vici,” and she murmurs back, “I love you, too, Roger.”

And then, Roger Smith knows he has it made—until, that is, 7:15 the next morning, when Vici nudges him, “Do you have to go to work early today, Roger?” And then, for some reason, unknown even to himself, he finds himself carrying on and deceiving his wife and confusing his children as he hears himself answer back: “No, not today, Vici.”

THE END

—BY SARA HAMILTON

SEE ROGER ON ABC-TV, FRI., 9-10 P.M. EDT, IN “77 SUNSET STRIP.” VICI CAN BE SEEN IN “BECAUSE THEY’RE YOUNG” AND ALSO IN “I AIM AT THE STARS,” BOTH FOR COLUMBIA PICTURES.

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE JUNE 1960