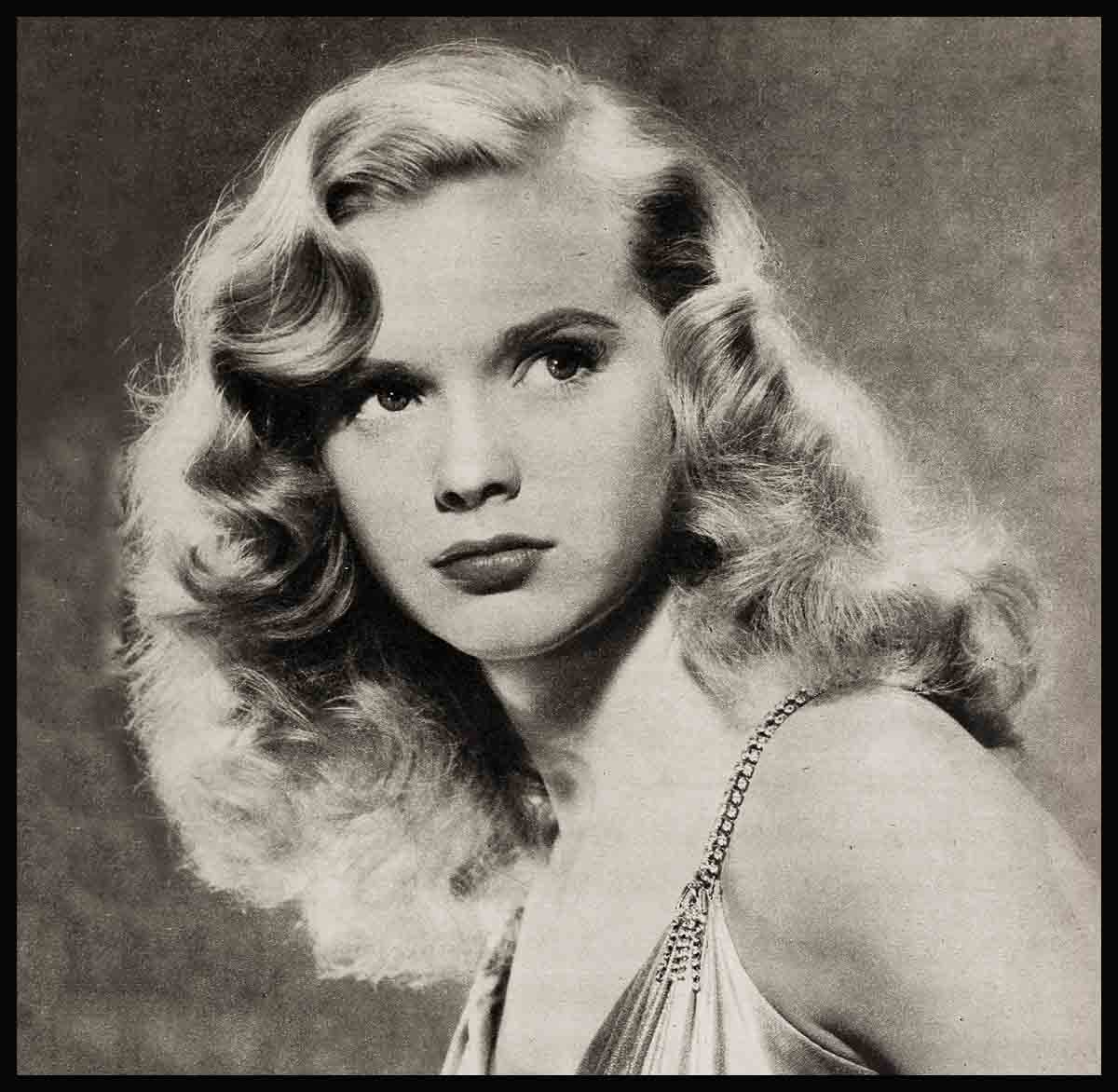

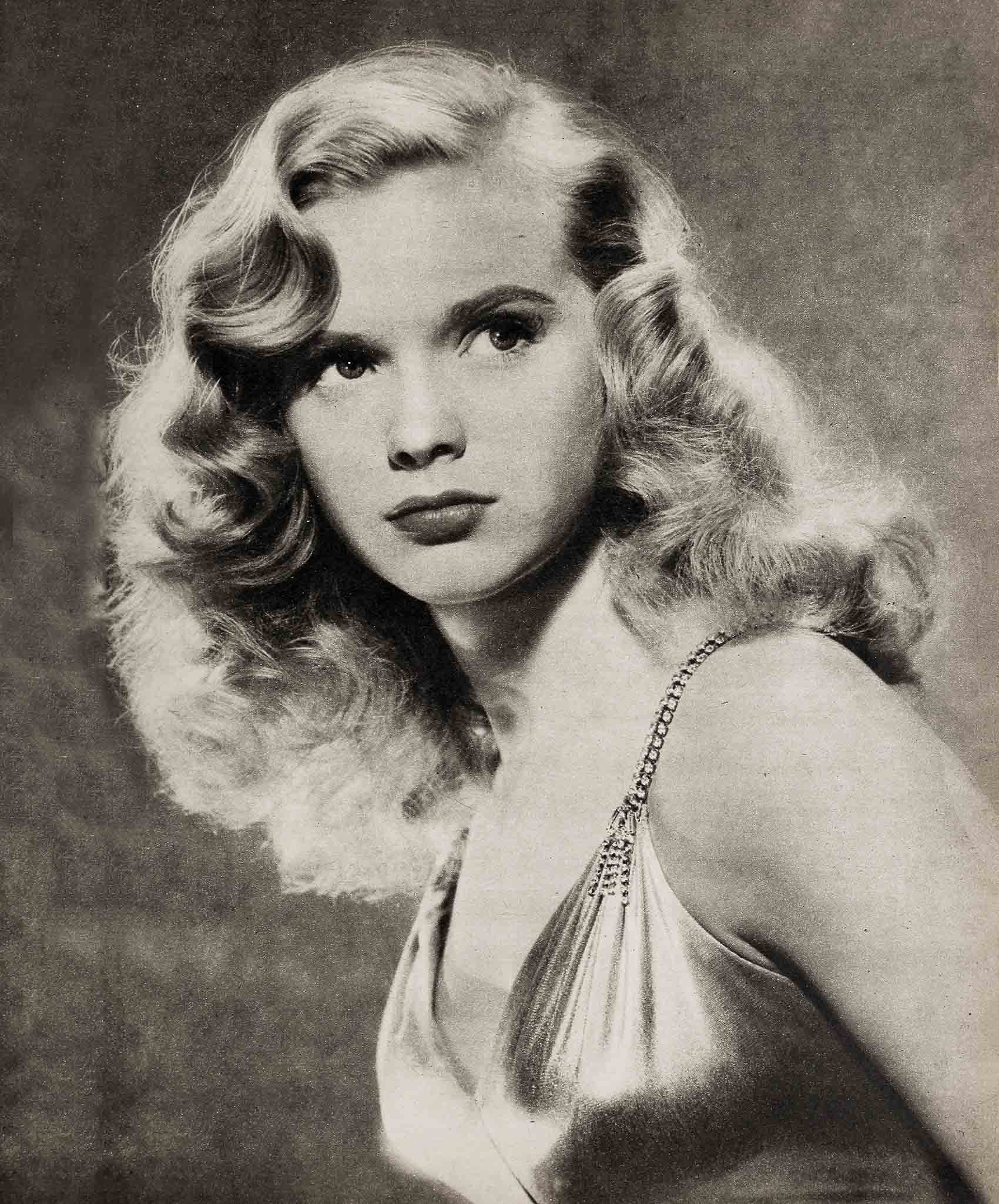

And Her Heart Went “BAM”—Anne Francis

The walls of Sing Sing Penitentiary all but leaned against those of the Ossining hospital where Anne Francis was born. Mrs. Francis was attended by the prison doctor and, while in labor, had the dubious pleasure of being serenaded by a continuous clanking on the rock pile. The fact gave relatives and family friends an opportunity for much ribbing, and among other jocular remarks was the prediction that, because of her start in life, Anne was sure to “go wrong.”

She began moving, all right, and has kept going at such a pace that by comparison Ossining’s most prominent citizens have been standing still these past 21 years. She did not, however, go wrong. Not only hag she kept out of the pokey and off of the country’s police blotters, but at the moment she is the shining new light on the 20th Century-Fox lot.

Moviegoers first saw her in Elopement, in which she played Clifton Webb’s daughter. Critics there said of her, “A new star is born. Anne Francis is a vital young lady of exceptional good looks—a dewy-eyed blonde with an appealing freshness and considerable talent.” Then came the lead in Lydia Bailey and her role as Webb’s daughter Once again in Dream Boat. By the time these films were ready for distribution, the master minds at the studio sat back and purred over the knowledge that they had once again picked a winner.

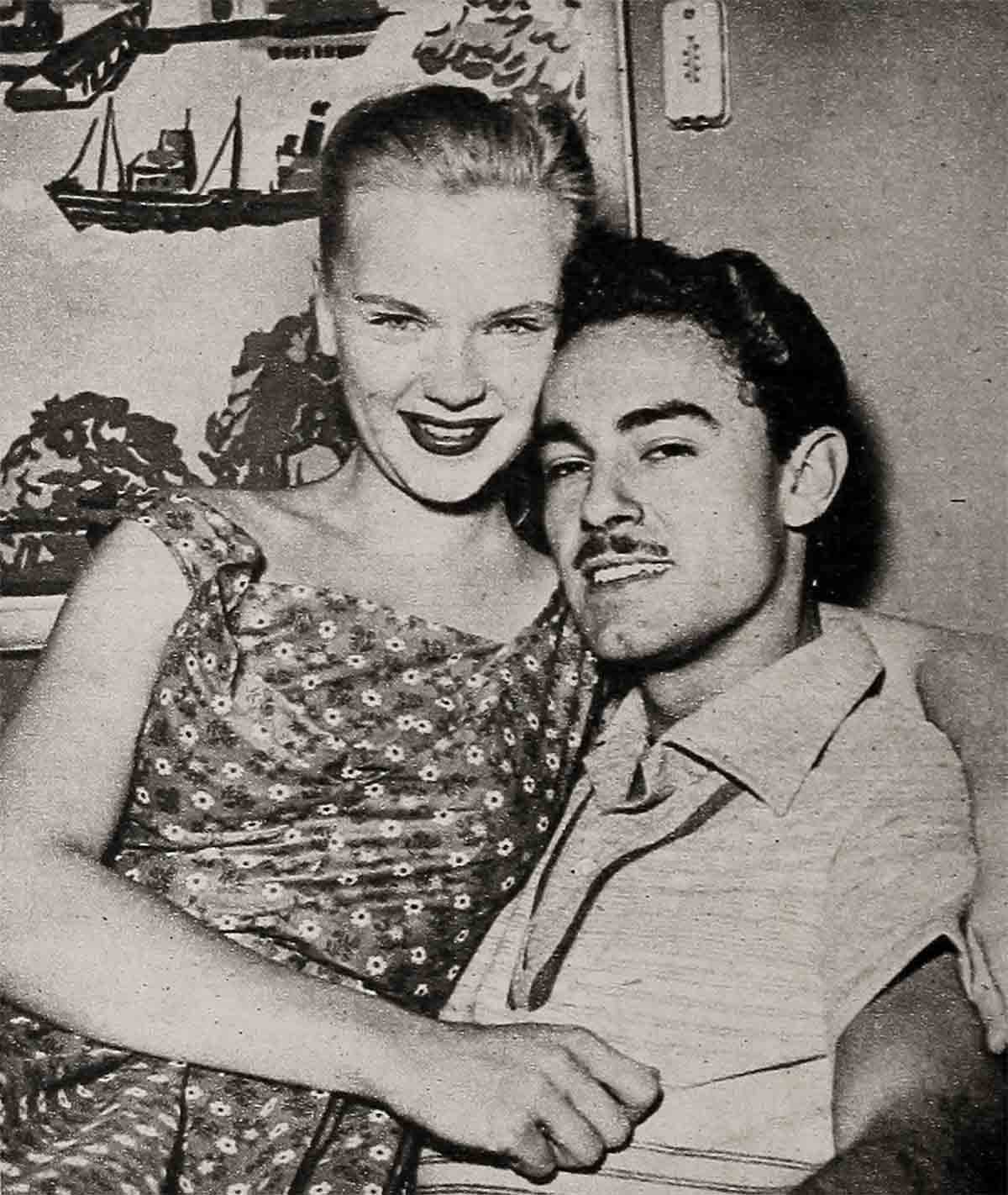

And while they were busy congratulating themselves, Anne momentarily and quietly slipped out of their fingers and into the arms of Bamlet Price, Jr., a dark, handsome veteran bomber pilot. The young couple, who had told no one of their plans, were married in a surprise ceremony, with only a few close friends and relatives present. Then followed a week’s honeymoon trip to Santa Barbara, Carmel, San Francisco and Yosemite. For Anne, who’s looking forward to raising a family, her marriage is by far the happiest achievement of her first 14 months in Hollywood.

That she landed in Hollywood at all is no surprise to Anne. When she was five years old she painstakingly scrawled her first written sentence—“I want to be a movie star.” The paper still rests with other mementos in a beribboned box tucked away in the family home.

The childish hope for the future may have been coincidence, but Anne’s talent was not. From the time she was six years old, most of her waking hours were spent before a photographer’s camera, a microphone, a theater audience or a television camera. She was kept so busy as a photographer’s model and an actress that public school was out of the question and tutors were hired to educate her. Back in those days, Anne sometimes envied the kids who went to P.S. No. 74. They went skating and swimming in the afternoons, and Anne sometimes wished she could join them instead of going downtown to pose for another magazine cover. But these were only fleeting moments of regret, for Anne liked her work. Now she feels it has been more than worthwhile.

She claims to have worn out two tutors before Miss Quinn came along. To Anne, then 13, the 20-year-old Miss Quinn seemed ancient and very wise. The teacher had a way of spreading her own enthusiasm for learning. Mathematics and geography were, brushed over in a cursory manner, and then the Misses Quinn and Francis really got down to brass tacks in a discussion of philosophy and life in general that went to a depth shunned by the average adolescent.

Anne is an exceptionally mature girl for her age, a natural result of her having spent so much time with adults. She has none of the giddiness associated with most girls of college age, and when occasionally she catches herself acting gayer than she feels, she pulls herself up short. She loves people, but as individuals and not in crowds. At a party she prefers to sit quietly in a corner and observe rather than join in the small talk. She likes to meet people slowly and take her time in getting to know them. Nothing irritates her so much as a new acquaintance who pushes too fast for a friendship.

People have described Anne as reserved, but it is not quite the proper word, for although she shows a great deal of restraint, her personality bubbles around the edges and there is a suspicion that she is holding back an innate gaiety. Perhaps it can be explained by the fact that early in life her career put the cap on an effervescent personality.

When Anne was still an infant, the family moved from Ossining to a small town in New York called Yorktown Heights. It was a country life, and Anne loved it. There were woods to roam and horses to ride and chickens in the back yard. Once in a while her mother would take her into New York City, only an hour away, to pose for a magazine cover. But back at home she could take off the fancy clothes, climb into something more comfortable, whistle to her dog and be off again to the fields. Then, when Anne was seven, the Francises lost their home. They moved into Manhattan where her father got a job selling at Macy’s and her mother picked up occasional work. The transition from overalls and bare feet to patent leather shoes and hat was made suddenly, and Anne simmered with resentment against the necessity of “looking like a lady.” She was a tomboy at heart—the fire escapes in back of the tiny three-room apartment were a sorry substitute for the meadows she had known.

But her career boomed. While she went on being a junior cover girl, she also entered radio, eventually becoming known as the Princess of soap opera. She was the first child actress to have her own television show, and for many years was much in demand as a fashion model. She worked in summer stock, and on BroadWay portrayed Gertrude Lawrence as a child in Lady In The Dark. In between jobs she visited agencies with her mother, looking for work. Even at the age of seven Anne was a true professional and knew instinctively the kind of smile or type of expression wanted by a photographer.

Her earnings were spasmodic, and most of the time infinitesimal. The Sunday radio program she called her own brought the munificent salary of two dollars per show. Anne worked not to add to the family coffers, but because she wanted to. The money she made was “put back into the business,” spent for clothes and her studies in dramatics, piano and singing, and for the other lessons that filled her days. Nevertheless, her parents were well aware that such a professional life was apt to spoil Anne, and they did everything in their power to keep her a normal youngster. There had been three babies before her, none of whom had lived, and it was difficult to deny Anne anything. They tried to teach her the value of money. Anne recalls one method in particular—if she was willing to walk the 12 blocks to Rockefeller Center, she could spend the bus fare saved for a book of paper dolls.

Anne was taught that a young lady never shows anger or temper or any extreme emotion, and in her effort to cooperate she bottled up a natural exuberance. Her emotions have been released in her acting, and Anne says today that if she hadn’t chosen to be an actress, she would now be a potential explosion.

This early training in restraint made her self-conscious, and her shyness increased when she began working with other professional children in New York. The others considered her odd because she was from the country, and although she made friends quickly, her whole life was to be affected by one particularly vicious small female who, jealous of Anne’s success, managed to turn her friends against her. Anne didn’t understand; she would find one good friend or a group of friends and be happy in their companionship until suddenly they would drift away from her, and sometimes even avoid speaking to her. The reserve that people notice in Anne today is the outcome of this experience, which happened in the sensitive years when she was entering her teens.

The change didn’t affect her career. It went right on scaring, and at about the same time her father found a more remunerative job. The family bought a house on Long Island, in East Rockaway, on the water. It was only a summer place, but Anne and her parents made it into a permanent residence. With the rise in the family fortunes she felt the world was growing brighter. Hollywood, by this time, was her affirmed goal. She haunted the neighborhood movie theaters and worshipped Alan Ladd from afar. To Anne, Maureen O’Hara was the most beautiful thing that ever flashed across a screen. “She looks the way a heroine should look,” Anne used to say.

She didn’t have long to wait, for when she was 15 MGM beckoned and gave her a one-year contract. Career-wise, it turned out to be the biggest disappointment of Anne’s life. She sat for the whole year, waiting for a role, and got nothing more than a brief walk-on part in a Mickey Rooney comedy. She found herself in front of the broom when the studio Swept out a lot of young hopefuls at the end of the year, and, disheartened, she went back home. Not long after, she was given a role in So Young, So Bad, a film about juvenile delinquency that was made in New York. On the strength of her work in it she was brought to 20th.

It was, of course, the turning point in Anne’s life. Her mother came to Hollywood with her and stayed for almost a year, during which time the mother-and-daughter team was swamped with pitiful letters from Mr. Francis, inquiring how to make an omelette and what herbs to put in a stew. After nine months Mrs. Francis felt that Anne was well enough established in her new home and went back to take over the kitchen in East Rockaway, much to her husband’s relief.

Neither parent felt any qualms about leaving Anne on her own. They would miss her, certainly, but from the first they had known that Anne was destined for a career and would one day want to leave the nest. They had every reason for confidence in their daughter. Anne was set to work in pictures immediately, and took the whole thing with a serenity that surprised Hollywood. No one knowing Anne’s background, however, could expect her to be non-plussed. She had behind her years of experience in every medium of show business, and neither cameras nor fame were unknown to her.

Anne has made a great many friends in Hollywood, but, unlike most newcomers, she hasn’t attached herself to one of the social cliques of the town. Her friends are mostly actors and actresses who are struggling along without contracts. They’re all around Anne’s age, and they are people who understand her, friends with whom she feels comfortable.

Before she met Bam, she was perfectly content to be by herself of an evening, reading, painting, or playing the piano. She’s a quiet, self contained person, and there’s never been the urge for her, as there is with must people, to always be with others. Sometimes she would eat out alone at a Westwood restaurant where she knew the piano player and the waitresses. Customers often turned to look at the attractive blonde sitting by herself in a corner and wonder, and Anne looked and wondered right back.

Now all that has changed. Anne and Bam (a family surname) were introduced for the first time by mutual friends last August. Later, when Anne moved to Westwood, she discovered that Bam had an apartment right next door. She also found out they had much in common, and they used to sit for hours discussing their ideas about life and work.

Bam, who’s studying for a Ph.D. in motion picture production, wants eventually to teach in the field of educational films. He is currently writing, producing and directing a short documentary on the evil effects of dope, and Anne is serving as his assistant director and producer. The two spent a recent week end scouting locations for the film near Lancaster, and finally discovering an ideal spot—a Joshua tree and cactus stretch that resembles the country around the Mexican border.

At the moment they are living in one apartment and using Bam’s as a studio and workroom. But they hope soon to find a larger place, perhaps a small bungalow house.

For an actress who has been in Hollywood such a short time, Anne seems to have her life well in hand. She knows what she wants, and if she is still a bit self-conscious in a crowded room, she is confident before the cameras. She is serious about her work and her marriage, and she is constantly seeking self-improvement.

THE END

—BY JANE WILKIE

It is a quote. MODERN SCREEN MAGAZINE SEPTEMBER 1952

No Comments