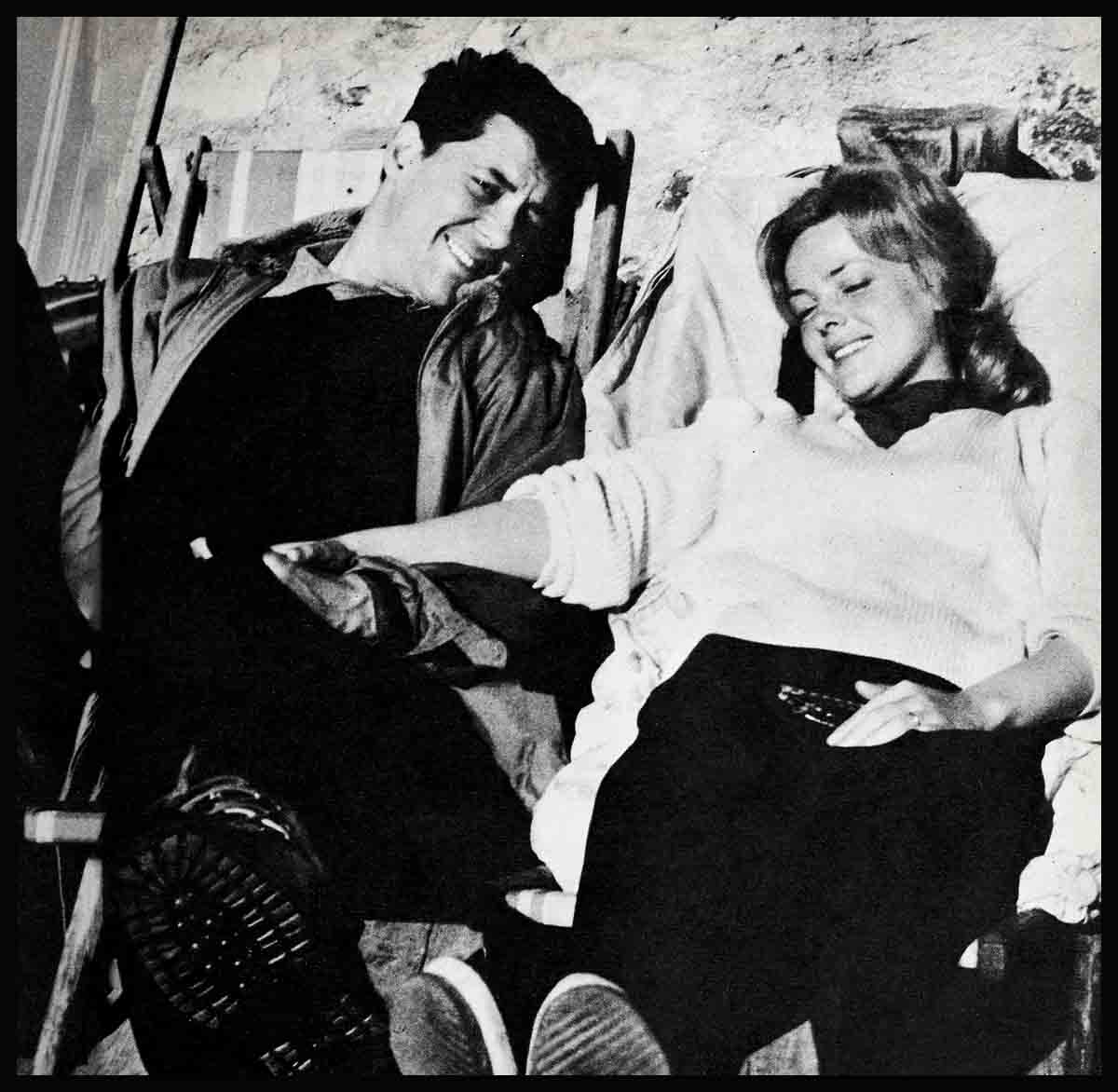

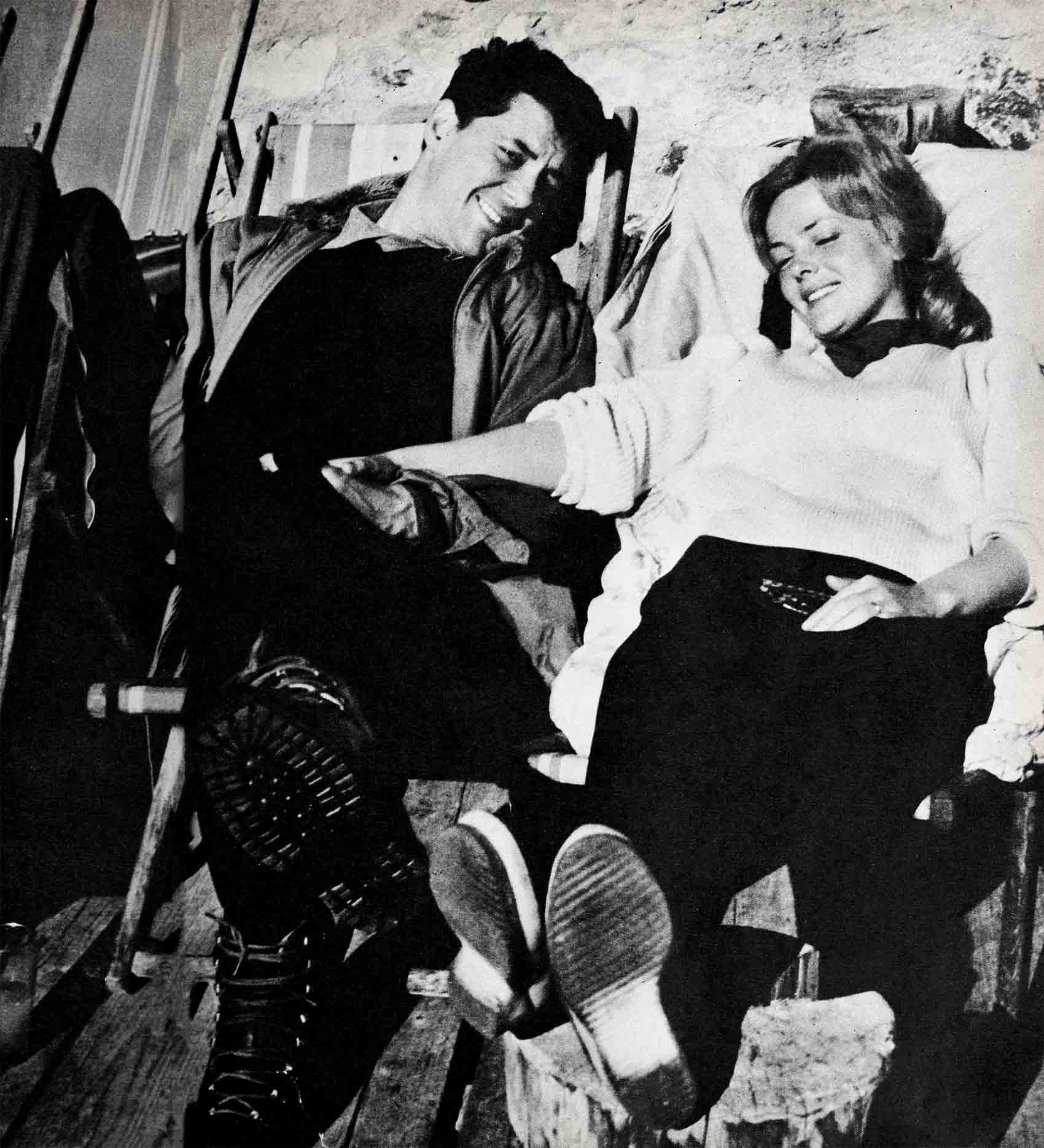

“I Want My Baby . . . I Want My Baby”—Christine Carère & Philippe Nicaud

The warmth of the sun felt good against my face, and, pushing up the sleeves of my heavy ski sweater to let its rays reach onto my arms, I relaxed back into a deep canvas chair. We were sitting—Philippe (my husband) and I—on the wooden sun-terrace of a ski lodge high in the French Alps. All about us we could hear the shouts and laughter of the skiers and if I lifted my head a little I could see them trudging up the snow-covered slopes and gliding down, time after time.

Then a crunching of snow just to the right caught my attention. A funny little two-year-old with a knitted bonnet came chugging by on a pair of baby skis. The pom-pom on the peak of the bonnet kept bouncing provocatively up and down as she went and suddenly I felt I wanted to cry.

Reaching out for Philippe’s hand, I turned towards him and as he felt my grasp he opened one eye sleepily and looked at me. “That . . . that little girl,” I said, pointing a finger towards the bouncing pom-pom, “She could have been . . .”

But Philippe wouldn’t let me finish my sentence, patting my hand gently and interrupting with, “It will be. It will be someday. You’ll see. The doctors were quite sure you could have another.”

I tried to smile but my lips were trembling. “But I want my baby . . . I want my baby now,” I whispered.

Philippe didn’t answer. There was nothing he could say. He just held my hand, understanding, I think, exactly how I felt as I watched the child chug onwards through the snow, stopping only for a second to call, “Maman! Maman!’ to a young woman who was standing talking with two other ladies a little further away.

I’d wanted so much to have a little girl or boy just like the one that had passed by. The slopes seemed vacant without my baby, as vacant as I felt. And, as I watched her disappear in the distance, I remembered, quite clearly, that day, the first time we had known for sure I was pregnant. . . .

It was a brisk day, windy and impatient, as Philippe and I, late as usual, hurried by taxi through the busy business section of Paris to keep our appointment with the doctor.

“Do you feel all right?” Philippe looked apprehensively at me, and I wanted to shake my head yes, but somehow I knew he knew.

“No,” I answered instead, wishing I could lie to him. “I’m sick. . . . I feel awful . . . I . . .”

“We’ll get out and walk the rest of the way. Maybe the fresh air will help,” suggested Philippe, calling to the driver to stop.

“Mmm. . . .” I agreed.

Philippe got out first and then helped me, kind and attentive and worried.

“I’m sure it’s not too bad. Maybe I’ll feel better tomorrow,” I told him. And he paid the man and took my arm as we began walking up the tree-lined boulevard. “Perhaps I’ve just been doing too much over Christmas.” I sounded confident enough but inside I was frightened. Because I couldn’t remember the last time I’d felt quite so sick.

“Do you think it might be a baby?” Philippe and I had already discussed this possibility, and now he must have been thinking it would cheer me up.

“That would be wonderful.” I smiled weakly as we walked on silently, Philippe holding onto my arm and guiding me gently along.

The doctor was very busy that day—and besides, had been called out on an slim, dark-haired young nurse asked if we’d mind waiting a while.

“That’s quite all right,” Philippe told her as she showed us into the reception room.

Picking up an old copy of “Elle” from a low table in the center of the room, I settled myself in a deep armchair while Philippe walked restlessly around for a few minutes, then also chose a magazine, and came to sit beside me.

I flipped through the pages but couldn’t concentrate, wondering all the time what was wrong. Was it a baby? Maybe. . . .

“What would we call it?” I asked Philippe, suddenly, as though he had been able to read my thoughts.

Looking up from his magazine, Philippe stared steadily ahead for a moment, then replied, “Yves is a nice name—if it’s a boy.”

“Yes,” I agreed, and then thought of it together with our last name which is Nicaud. “Yves Nicaud,” I said slowly. “That sounds quite musical. And what about Catherine, if it’s a girl.”

“Or Isabelle?”

And we found ourselves playing the name game that all young couples play when they first realize a new member of the family might be on the way.

“Philippe . . .? What if . . . what if I’m not . . .what if . . .”

“Darling, don’t worry.” He spoke very softly, reaching out to tuck a stray curl under my scarf and smiling the way he always does when I’m worried or frightened.

“I expect you’ll want the nursery blue and white,” he said lightly, evidently trying to lessen the tension.

I had to laugh. Ever since we first met and married three years ago while working on a film together, it had always been a big joke between us. “Blue and white I adore but I can’t stand green,” I had said.

“And it will have to be modern—we can’t have antique furniture like in the rest of the house,” I said.

“It’ll mean goodbye to our guest-room plans then,” Philippe concluded. “Anyway, that room will look much nicer as a nursery.”

“Oh—Philippe. A baby—how can you be so sure?”

I noticed Philippe glance up every now and then at the big grandfather clock by the wall and as the slender minute hand neared the half-hour mark Philippe closed his magazine and placed it back on the table.

“Darling . . .” he began. And I knew the rest.

“Go ahead, you can’t be late for the show—I’ll be all right,” I said quietly, knowing he had to make curtain-call on time. But suddenly I felt myself becoming terribly tense at the thought of being left all alone. I was afraid.

“You’ll call me at the theater as soon as you’ve seen him? Promise?”

“Yes, I promise.”

The room seemed very quiet without Philippe and my mind began forming all sorts of horrifying pictures. I’ve been afraid of being left alone since I was a small child in France during the war when I used to be terrified that the Germans would take me away.

Then, as I sat there all alone, flipping nervously through the shiny pages on my lap, I couldn’t help thinking of all the other women who must have waited in this very spot wondering and wondering . . . the things that I was wondering.

The door clicked open. I turned to look. It was the white-coated nurse, smiling, and saying, “Mme. Nicaud. Would you please come this way. The doctor will see you now.”

Getting up slowly, I left my magazine on the chair and turned to follow her out of the room, feeling my heart beat just a little faster than usual as we walked through the hall into the doctor’s office. Then I saw him, sitting behind his wide oak desk at the far end of the carpeted room.

He was a well-built man with greying hair and a relaxed expression that made me feel at ease almost at once.

“I’m sorry to have kept you waiting so long, Mme. Nicaud,” he said, getting up and coming around the desk to shake my hand.

Then began the questions and the examination and finally, finally . . . somehow the wonderful words he was saying seemed to be coming from very far away. . . . “Yes, Mme. Nicaud. There’s no doubt. You are pregnant.” Then he added, “But you are extremely run down and you must go straight home to bed at once and rest. The vitamin and iron shot I have just given you will build up your strength but you must promise to get rest and more rest.”

“Oh—I will, I will,” I assured him, twisting impatiently in the chair, anxious to call the theater and tell Philippe the news.

I think the doctor must have known what I was thinking because he laughed and said, “Go ahead. Use my phone. I know you won’t listen to a word I’m saying until you speak to your husband.”

My hands were trembling as I dialed the number and I must have been so excited that for a brief moment I couldn’t remember the last two figures. As I listened to the phone ring I looked down at my watch. It was 10:15. He should be offstage by now for it was almost intermission time.

“Ambassador Theater—stage door,” growled a voice at the other end.

I asked to speak to Philippe and it seemed an eternity before I heard that familiar “Hello” at the other end of the line.

Then he said “hello” again and then again. Because all of a sudden I just couldn’t speak. Somehow the words just wouldn’t come out. Finally I stuttered, “Philippe?”

“Yes, darling. What . . . what did he say?”

Philippe sounded so excited, so impatient to know.

“It’s true . . . I’m . . . I’m . . . really going to have a baby,” I blurted out and I could feel tears coming into my eyes.

Philippe’s parents were visiting us from their home in Jura, in Eastern France, at the time, and I couldn’t wait to get home to tell them the news—and also to call my own mother.

A taxi dropped me right at the door of our apartment house, and as I went up in the elevator I began thinking of how I would tell them, having a magnificent time rehearsing the scene to myself.

Taking the key from my handbag, I opened the door and walked inside. Philippe’s mother and father were sitting quietly in the living room and as I went in, they both looked up. Then, before I had a chance to say anything Philippe’s mother screamed, “You’re going to have a baby! That’s what the doctor said! I can see it written all over your face!”

She ran over to me and began hugging and kissing me and Philippe’s father came over to kiss me too.

Then she called out for Adele, the family cook who’s been with them since Philippe was five years old. “Adele, Adele!” She cried. “We’ve wonderful news. Christine’s going to have a baby.”

I still had my hat and coat on.

Adele, a large, plump woman, came waddling out of the kitchen and almost knocked me over in her shower of affection. “A baby!” she screamed. Then, hands on hips, she told me firmly, “You should have a girl. Girls are much easier to raise than boys and don’t get into so much mischief.”

“I’ll make sure it’s a girl just for you, Adele,” I promised, laughing.

“Now, I must call my mother,” I told them, maneuvering myself out of the excited group and walking towards the telephone which stood on a low table in the hall.

“Maman!” I said excitedly as I heard her voice. “I’m going to have a baby!”

“At last I’m going to be a grandmother!” she screamed, and, not letting me get another word in, continued, “Are you sure you’re all right? Should I come over right away?” She asked so many questions.

“No, Maman. I’m quite all right. I’ll see you first thing in the morning.”

Then as we hung up I heard her mumble, “Now where did I put my knitting needles.” She’s always so practical. And I knew how thrilled she must have been because she’d been placing all her hopes of being a grandmother on me, since my only brother is very much younger than I, and, of course, not yet married.

I heard a patter of paws behind me and turned to see Fortiche, our cocker spaniel, wagging his tail almost as if he, too, wanted to congratulate me. And he began running around and around in circles, confused, I think, by all the excitement.

I pointed a finger playfully at him. “Fortiche,” I said, “you’ll just have to get used to not being the center of attention anymore.” And from the way he whined as I spoke, one could really believe he’d understood.

I was actually a little worried about having him around with a baby in the house, but everyone assured me that cocker spaniels are angels with children.

Then the front door opened and it was Philippe. I ran to kiss him.

“So it wasn’t just wishful thinking,” he laughed.

“And we will have that blue and white nursery after all,” I said.

“With a blue and white crib, blue and white toys, blue and white . . .” We were laughing so much.

“And we’ll take him—or will it be her— to Hollywood with us. . . .”

“He’s got to spend some time in Paris, though . . .” As he said this, Philippe looked serious for a moment.

“And I’ll sew wonderful little things for the baby while we’re waiting . . . and stay with you here in Paris. . . .”

“You can even write that novel you’ve always talked about. . . .”

“And . . . and . . .” There was so much to say. . . .

“Christine! Christine!” Someone was shaking my arm and I was brought sharply back to the present. It was Philippe. “Do you know you’re laughing yourself?”

“Am I?” I said rather wistfully. Because now there was nothing to laugh about any more.

The shock that shattered all our dreams came about six days after that wonderful night when we’d first known I was pregnant. . . .

It was evening, cool and clear, and one of those nights when all Paris seemed to sparkle with excitement and life. From our apartment high in Montparnasse I could see over the rooftops and hear the cries of the people, happy people, in the streets.

I was resting in bed, chatting with my mother. Philippe was at the theater. Beside me on the quilt lay the patterns and pieces of fabric for a baby’s playsuit.

“Maman. I said. But as she picked up the spool from a round table beside her and held it out to me, I was suddenly struck by a sharp pain.

“Maman!” I cried out.

“What’s wrong?” she screamed, rushing to the bedside as I began to groan and twist.

“I . . . I . . .” But I couldn’t speak.

Then, still twisting from side to side in an effort to stop the agonizing pain inside of me, I watched my mother as she went over to a small table by the side of the bed and telephoned the doctor—without saying another word. She looked terrified. “He’s coming right over,” she said, finally.

I couldn’t stop turning and turning as though an inner sense told me that by moving I would lessen the pain. But it got worse and Mother had to call to Adele to help hold me still.

It seemed so long before the doctor arrived. He looked very grave, and, as he examined me, he kept nodding to himself in a way that made me very frightened.

“It’s not . . . I’m not . . . I’m not going to lose my baby,” I managed to whisper. I was so afraid.

He didn’t answer immediately. Then he said, “I can’t be too hopeful for you.”

I wanted to cry. And I think, for that one moment, I really wanted to die.

They carried me downstairs into an ambulance. The physical pain was terrible and all the while I kept thinking of Philippe and how at that moment he must have been such a happy man, enjoying the feeling that he would soon be a father. We couldn’t contact him immediately because he was onstage, so he didn’t know what was happening to me . . . so he didn’t know that all our plans seemed to be evaporating into mere dreams . . . that Fortiche might have to wait a long time for a new playmate . . . that there might now be no point in turning the guest room into a nursery.

Then all these thoughts became a jumble in my head until I must have fainted, because the next thing I remember was finding myself lying in a narrow hospital bed and opening my eyes to see Philippe standing by me.

He looked so solemn, so downcast, that despite his cheerful, “Hello. Did you sleep well?” I knew that what I’d dreaded most had happened. And I started to scream hysterically.

“I want my baby. . . . I want my baby,” I cried, and the tears came streaming down my face.

The doctor came to the bedside. He took my clenched fist in his hand and started speaking softly. “You mustn’t cry . . . you must be brave. . . Your husband is just as upset as you are, but he’s calm . . . you must be calm too. . . .” But I just went on crying. I couldn’t help it.

Then he changed his tone and became firm. “Think of the other patients in the hospital. Some of them are far worse off than you. It’s not fair to keep them awake by your screaming.”

So gradually I calmed down and stopped crying.

Philippe stayed with me all through the night, holding my hand tightly as I kept waking from a fitful sleep of nightmares.

“What if I can’t have any more?” I screamed out, time and time again.

And each time Philippe would answer softly, “You can. The doctor assured me you can.”

I tried to believe him. . . . I wanted to believe him but I was haunted with the idea that this miscarriage had done something to me so I couldn’t have another child. And I kept thinking about the baby I could have had, being tormented more and more each time I heard a baby cry down the hall. I envied their mothers.

“Philippe—you’re not angry with me?” I said at one point that night, feeling as though I’d let him down.

“Of course not. Take the idea right out of your head,” he scolded. But I couldn’t stop worrying.

They were the most anguished hours of my life. I could not reason with myself, my fears seeming to grow all out of proportion.

The next morning the doctor came to see me, and my mother was with him. He drew up a chair by my bed.

“I hear that you don’t think you can have any more children,” he said, kindly but firmly.

“Well . . .” I stuttered.

“Well, don’t worry,” he interrupted. “You’re quite all right. You’re just the unfortunate result of fatigue and excessive exertion before pregnancy—it happens every so often. But I want you to know you’re one of the healthiest specimens I’ve ever had the good fortune to treat. You were just physically run down and your body didn’t have time to get its strength back.”

I smiled but inside I felt vacant and lost. I wanted my baby now . . . not in the distant future. And in the back of my thoughts I could hear him droning on . . .

“You must take a long rest,” he was saying. “Try to go to the mountains for a few weeks when you get out of the hospital and in four months you can start thinking seriously of starting a family—with no qualms at all.”

Then he left me alone with my mother. Philippe had already gone home for a few hours to rest.

For one of the first times in my life I felt completely hopeless—almost dead, and could find nothing to say to my mother as she chattered to me.

There was nothing to plan for any more. . . .

A shiver ran right through my body. I opened my eyes and found that the sun had gone behind the snow-topped hills and that it was getting very cold. I looked up and saw there were only a few skiers left on the slopes.

I patted Philippe gently on the arm and he opened his eyes. “Wake up, darling,” I said. “Look at the time—it’s almost six.”

I pulled down the sleeves of my ski sweater and zipped up my top jacket.

“But I was having such a good dream,” grumbled Philippe, playfully, as he lifted himself reluctantly from the deck chair. I took his arm and we walked slowly back to the hotel . . . the two of us, alone.

After my vacation I should like to make another film. I’m going to Hollywood soon and with Philippe busy with his new play—the French version of “Reclining Figure”—the doctor’s time period should pass swiftly.

And then, perhaps, I won’t feel quite so sad.

THE END

—BY CHRISTINE CARERE

WATCH FOR CHRISTINE IN TWENTIETH’S “A PRIVATE’S AFFAIR.”

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE JUNE 1959