Call Your Friend Rory Calhoun At Hollywood 5-2027

Dear Buddy,

I never heard of you till yesterday. I don’t know where you are or what you do or if you’ll ever get to read this. I hope you do read it though, because it’s really a message to you from an old pal of yours—Rory Calhoun.

I was having lunch with Rory yesterday, a casual let’s-get-together lunch. We talked about lots of things. Rory’s a funny guy and we did a lot of laughing.

Then, somehow, we got to the subject of friends. We were still laughing, exchanging stories about goofy experiences we’d both had with friends in our lifetimes, when all of a sudden Rory put down his fork and stopped laughing and clammed up. For a minute, I thought he was a little sick. For another few minutes, I didn’t say a word. Rory was staring over my head now, looking out into the middle of the restaurant. It didn’t take me long to realize that Rory was thinking about something, thinking hard about something. I picked up my cup of coffee and took a sip. I was putting the cup down when, very softly, Rory said, “You know, I was just thinking about the first friend I ever had.” He smiled as he said that, the smile of a guy who was remembering something from long ago that was good and bathed in all the nicest things in life. “His name was Buddy,” he said. “Buddy D. . . .”

(Editor’s Note: In order to respect Buddy’s right to privacy, we’ve decided not to print his full name.) He may not wish to be bothered by friends calling him up and telling him to get in touch with Rory. However, we hope Buddy D. will read this story himself and contact his old pal.)

Rory shook his head. “How many years has it been now?” he half-asked himself. “Sixteen, maybe seventeen,” he half-answered. He was quiet for a few more minutes after that, Buddy. In those few minutes he was back, past all those years in between, with his first friend, with a tow-headed kid with straight blond hair and a pug nose and a couple of hundred freckles and scraped knees—with you, Buddy.

When he began to talk again, he was still kind of half lost in that childhood world you both shared up there in the town of Santa Cruz. “It’s funny how Id forgotten so many things,” he started to say. And then he began to remember. . . .

He told me how he was six or seven when he first met you. It was about midsummer. You’d just moved to Santa Cruz from a nearby town—Rory’s forgotten which one. You were from a pretty poor family, like Rory’s—and like most of the poor kids in Santa Cruz you used to have your summer lunches on the beach, courtesy of Mother Nature and the Pacific Ocean coming up with a couple of dozen clams.

Do you remember that particular day when Rory—a tall, gangling kid with curly black hair and sky-blue eyes—came up to you there on the beach that first time and said, “Look, if you’re gonna eat dinkys, you’ve gotta eat them right.”

Rory remembers how you looked up at him and said, “I eat dinkys anyway I want to eat them.” With that, Buddy, you squeezed open another clam with your penknife, brought it up to your mouth and swallowed it down.

“Look,” Rory said, kicking the clam out of your hand, “you’ve gotta eat them with lemon juice. That’s the way the Chinese people around here eat them. That’s the best way.”

“I don’t have any lemons,” you said.

Rory explained. “There’s an orchard up there where they grow lemons,” he said. “Come on. We’ll go get some. We don’t take the ones growing on the trees. We take the ones on the ground, but those ain’t rotten yet. Okay?”

“Okay,” you said.

Fifteen minutes later, you were both back on the beach, four pockets bulging. You waited for Rory to dig up his batch of dinkys from the mud and then you both sat down on the sand for lunch. Rory cut the first lemon and did the squirting, first on his dinky, then on yours.

“Pretty good,” you said.

“Pretty good?” Rory questioned.

“Very good,” you admitted.

With this, you both exchanged your first smile. Then, while he began to squirt his own dinkys, Rory asked you your name.

You told him yours and he told you his—his was Francis Timothy Durgin back then.

“You wanna be my friend?” Rory asked next.

“Yeah,” you said.

“And so it began,” Rory told me in the restaurant yesterday, remembering. “Buddy and me, the most live-it-up pair of kids you’ve ever seen. . . . We used to do everything together, everything. We made rafts and played Robinson Crusoe on ’em together. We stole milk bottles together. We pulled girls’ braids together. We were even in the same class in school together. School! Now there was a place Buddy and I really liked. We used to spend half our time wondering why they had them in the first place. And we used to spend the rest of the time talking about how we could have been out fishing and digging for dinkys and running around and swimming. And sometimes we did.”

There are two days in your lives together, Buddy, that Rory remembers more than any of the others. Both of them stand out because they were days you got sore at each other, real sore.

The first crisis happened when you were both nine. It centered around Rose-Rose. Remember Rose-Rose? She was the pretty blonde Polish girl in your school—all of eight years old, at the time—and it was her birthday and another girl from school was having a party for her. Both you and Rory were invited to the party. Both you and Rory had a crush on Rose-Rose and both of you very gallantly asked her if you could pick her up at her house the day of the party and walk her to her girlfriend’s. Rose-Rose probably liked both of you very much because even though you and Rory had asked her separately, she’d said yes to both. When you and Rory found out about this on the morning of the party, you both felt like hurt puppies but growled at each other like proud bulldogs.

“I asked her,” Rory said, giving you a poke.

“So did I,” you said, poking him back.

For a while there, it looked like there’d have to be a duel at dawn just to get things straightened out. And then—remember, Buddy?—Rose-Rose came down with whooping cough and the party had to be called off and nobody was going to get to take any pretty blonde to any birthday party. That afternoon, in case you’ve forgotten, you and Rory shook hands, swore off girls forever and went down to the beach to roast some potatoes.

The second crisis happened when you were both twelve or thirteen. It centered around the Santa Cruz Junior Yankees and its two leading batsmen. You and Rory played on the team—were the two leading batsmen, in fact. You called yourself Babe, after Ruth. Rory called himself Lou, after Gehrig. One day the kid who called himself Tony, after Lazzeri, began razzing the two of you about who the really better player was. You’d never thought much about it before this. But little Tony taunted on and on to the point where you found yourself saying:

“I’m am.”

Rory didn’t like this. So he upped and said “I am.”

Can you ever forget the game that afternoon, the batting duel to decide once and for all? And can you ever forget how both you and Rory went completely hitless that afternoon and how little Tony ended up getting two homers and a double and sticking out his tongue and declaring: “I am!”

The next few years went quickly and, before either you or Rory realized it, you were young men. You got a job out of the state at this time and left town. You promised to write to Rory and he to you. But neither of you did, because things happened.

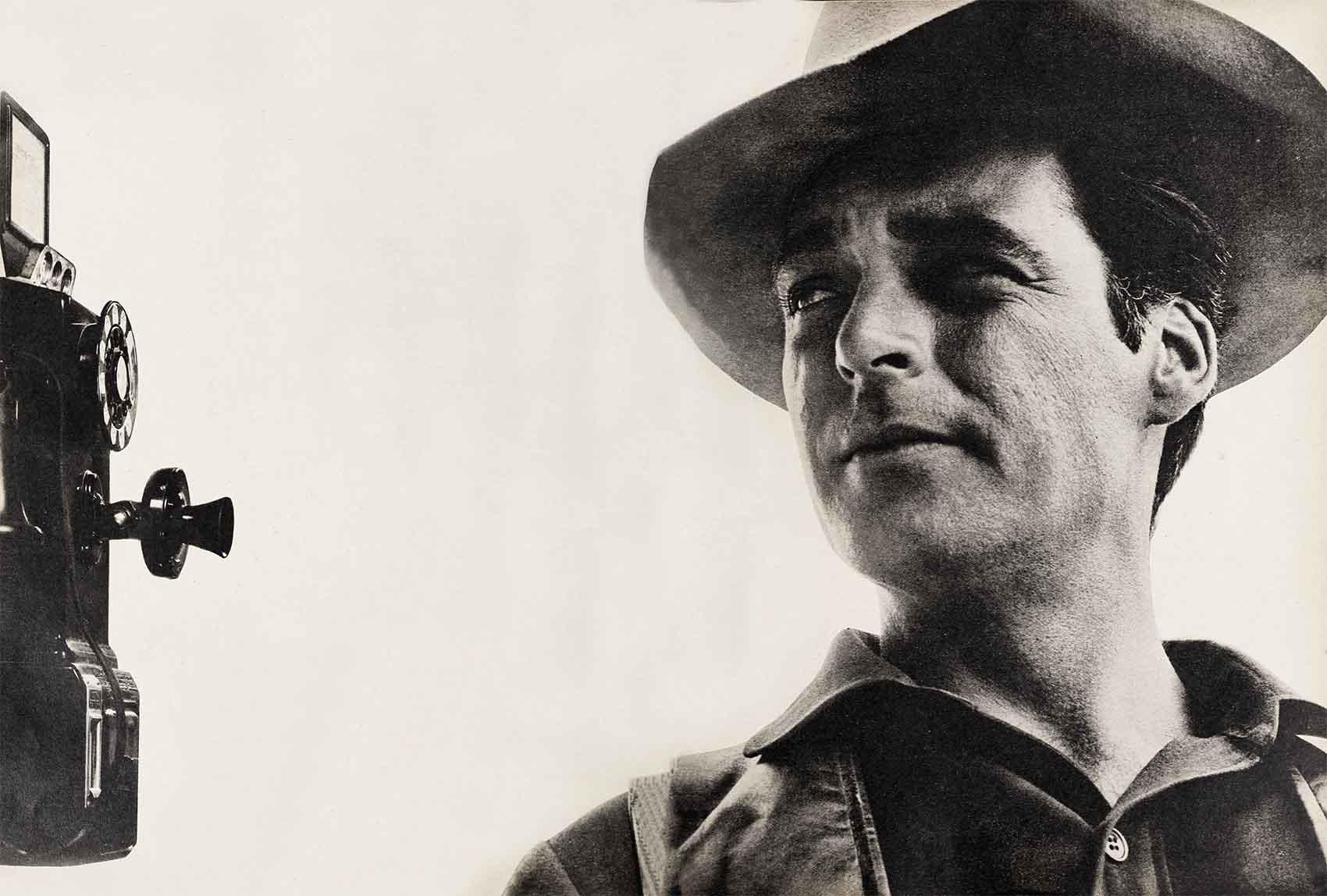

Rory doesn’t know what happened to you. He remembers what happened to him—the trouble he got into with the police and the months in jail; his talks with the kindly priest who helped him to leave the jail a new man. His visit to Hollywood and the chance meeting with Alan Ladd on a lonely horse trail, a meeting that eventually made him into the big movie star he is today.

You probably know the details of those few bad years Rory had before coming to Hollywood. Practically everyone who can read does. But just in case you think your old pal had it easy from the day he got here, that it took a single lucky break to get him riding on the pinnacle he’s riding today, listen to what he’s got to say about those first years here in movie town. And see if maybe you didn’t have problems like this when you left Santa Cruz for whatever life you decided to cut out for yourself.

“Alan Ladd and his wife thought I’d be good for pictures,” Rory will tell you, “and they helped me get my first job. I got a contract at TWENTIETH CENTURY-FOX through them. Most guys were off in the service at this time and they were putting anybody and everybody under contract. I started at $100 a week. Not bad, I thought. I’d certainly never seen that kind of money before. Except that what the studio forgot to tell me was that with this money I had to get me a whole batch of new suits and take a whole lot of starlets out so I could be seen. I just plumb couldn’t afford this kind of living, so to make some extra dough I drove a wrecking truck most nights and on Sundays I got a job at a gas station.

“And if this business of going out with starlets a couple of times a week at the beginning of a career sounds like jim-dandy fun, let me tell you this: It isn’t exactly hard work sitting at a restaurant table with a beautiful girl, no. But when all you want to do is talk about fishing and hunting and the things you love, and all they want to talk about is Shakespeare and the Russian method of acting as opposed to the Hollywood method—look out because it can get pretty dull. And it’s costing you a small fortune, to boot.”

You’ll be happy to know, Buddy, that Rory shoved all this would-be high-hat living aside once he got his first big break. And that he’s still the kind of guy who chooses his pals carefully, who can tell the square-shooters from the round kind, who knows a good guy when he meets one and who values a good guy the way most people value their very lives.

I asked Rory about some of these friends yesterday and here’s what he said:

“Ricardo Montalban. Here’s one of my best friends. He’s my compadre, too—my baby Cindy’s godfather, Ricardo’s a swell guy. He’s an all-the-time-the-same kind of guy, full of energy, always happy to see you. If you suggest something and he’s never done it, he goes after it with all kinds of intensity just to please you. This is a pretty admirable trait in anybody.

“Jim Webb’s another friend. I believe he’s called James Watson Webb Jr., if you want his full title. I met him when I first came to Hollywood. He’s a multi-millionaire who wanted to work and become a director some day and so he got a job at Fox, editing film. I was with FOX for one year at the beginning and a publicity girl was asking me all kinds of questions for the biography they were doing on me. When it came to hobbies, I said I liked hunting and fishing best. She said, ‘Oh, you should meet Jim Webb—so does he.’ We met and we’ve been friends ever since. Jim’s the kind of guy you don’t see in six months and yet you still feel free to call on. When you do, it’s like you saw him yesterday.

“Guy Madison’s another good pal of mine. He made an impression on me as a loyal-type fellow the first time I met him. That was when I was with Selznick, about twelve or thirteen years ago. Guy was in the Navy then. We started out by going on hunting and fishing trips together. We still do. Guy’s the one who got me interested in archery, by the way, and introduced me to Howard Hill, the greatest archer in the world and another pal of mine.”

And so Rory talked, Buddy, about his pals and the qualities in them that made them his pals. And then, as he had about an hour earlier—it was about 2:30 now and the restaurant was practically deserted—he stopped talking again and again he looked straight ahead and straight back into the past.

Finally, when he did speak, he said, “I wonder what Buddy would say if he could see my baby right now.” He smiled. “I know he’d be crazy about Lita,” he said. “Here’s a wife who’s always looking out for me. She’s for me, with me and backing me up all the time. Buddy would like her. Yeah, he’d like her fine.”

I asked Rory if he had any idea where you might have gone when you left Santa Cruz.

“No,” Rory said, “no idea. But I’d sure like to see him or hear from him again,” he added.

A waiter came over to our table now and asked if we wanted another cup of coffee or something. We said no thanks, and then decided it was time to go.

I was taking a cab back to my office and so I left Rory outside the restaurant. We shook hands, said good-by let’s get together soon or whatever we said. Then Rory walked up the sidewalk to the parking area alongside the restaurant where he’d left his car.

I watched him as he walked. He’s usually a pretty snappy walker. But yesterday, when we parted, he walked slowly, very slowly, his hands in his pockets, his eyes up in the sky somewhere. And I know that as he walked he was thinking about a little blond kid and about dinkys with lemon juice and about Rose-Rose and a birthday party and about the Santa Cruz Junior Yankees and about how he’d like to hear from the little blond kid again and re-live all of those memories for just a little while.

In case you ever get to read this, Buddy, why don’t you give Rory a ring? He’d like that. His number is Hollywood 5-2027.

Sincerely,

Ed Ritta

Watch for Rory in U.A.’s Ride Out For Revenge, MGM’s The Hired Gun and Columbia’s Domino Kid.

It is a quote. MODERN SCREEN MAGAZINE AUGUST 1957