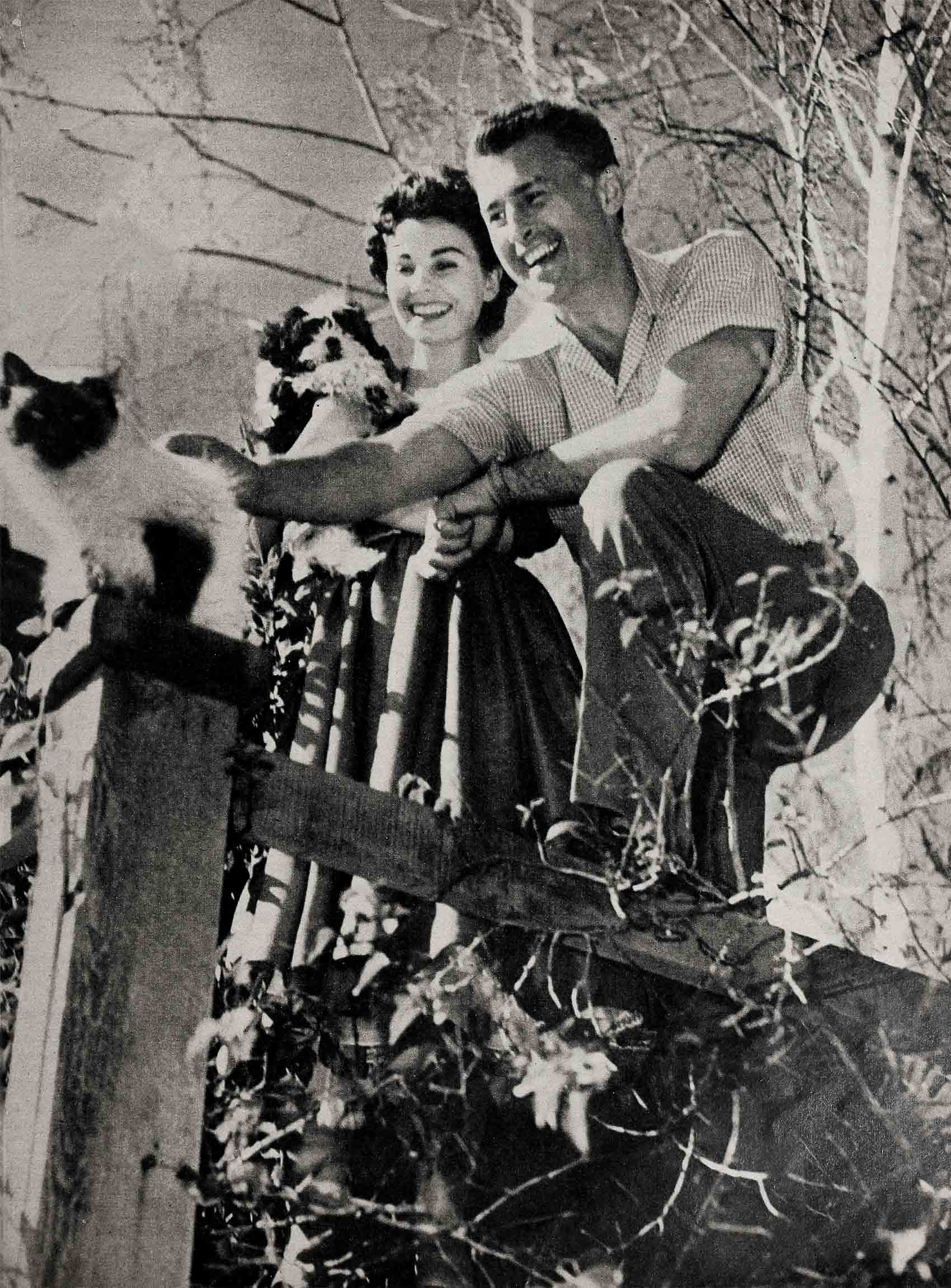

. . . And Baby Makes Five—Stewart Granger & Jean Simmons

His long legs outstretched, Granger took a look at his wife, tucked handily into a big chair opposite. He spoke with appreciation. “A model mother-to-be. Never a sick day out of her. Knock wood.”

“Except once,” Jean remembered. “Because I stuck my toothbrush too far down my throat.”

“Which in charity we’ll overlook.”

“And right noble of you, sir.”

“Think nothing of it.”

The room lay bathed in late morning sunlight. One windowed wall faced the grounds, where a gardener ministered to a new Chinese elm, maltreated in transit. To Granger, a tree is little less than sacred. His eyes kept traveling to the ailing elm and back.

Waiting for parenthood, Jean’s happy and relaxed. Jimmy’s happy and less relaxed. He of the logical mind finds logic forsaking him where the baby’s concerned. Candidly he admits himself superstitious. “It upset me that the news should have broken so soon. I’d rather have kept it quiet for two or three months.”

“Try keeping me quiet that long,” murmured Mrs. Granger, no whit abashed, though they both knew it was she who had broken the news. “But not to the columnists,” she explained, all innocence. “Just to fifteen or twenty friends. And in strictest confidence!”

As a rule, it’s Jimmy who’s the master-planner. For this occasion he refuses to make plans. “There’s a room ready. When the baby’s here, we’ll start decorating the room.” He won’t discuss possible names. Asked for his preference as to gender, he replies with finality: “I want a baby.”

“Me, too,” agrees Jean, and plunges cheerfully on where Jimmy fears to tread. “But I have a feeling it’s going to be a girl.”

Lindsay and Jamie own a special stake in the baby. “They rather think it’s coming,” says their father, “because they asked for it.” Last fall, their mother being ill, he brought the youngsters over to make their permanent home with him and Jean. At ten and not quite twelve, they still inhabit the semi-wonderland of childhood, where magic dwarfs reality and wishes, properly made, are bound to come true. “We’d like another little chap around the house,” they’d suggest at intervals, and feel gratified—though not greatly surprised—that the chap’s en route.

Actually, they may be wiser than they dream in claiming part of the credit. Jean of course has known them ever since she’s known her husband. They’ve crossed the sea on visits. Visiting and living, however, are two different things. During their few months in residence, they’ve wrapped themselves securely round her heart. “I grew to love them so much that I realized how dearly I wanted one of my own.”

Whatever their share in promoting a new baby, they’re wholly responsible for the new house. Or, more accurately, for the sale of the old one. “That eyrie,” says Granger, “was ideal for two bachelors. But suddenly we inherited two children and now at once the house becomes too small. There was also the cliff. Visions began to haunt me. I saw my lively progeny tumbling over the edge, tangling with poison oak and rattlesnakes, possibly breaking a small bone here and there. This didn’t conduce to restful slumber. It was then that I hatched a major inspiration. ‘How,’ I asked Jean, ‘would you like to live in Switzerland?’ ”

For so drastic a change, he had solid reasons to advance. Jean has a mother in England whom she loves. So has Jimmy, so have the children. From Switzerland, they’d be more accessible to one another. Switzerland teems with wonderful schools for kids. The plane service is superb. Two hours or less would take them to Rome or Vienna, to London or Paris. They could work in England or on the continent. They could fly back to Hollywood when Hollywood called.

Jean agreed, apparently without reservations, and departed for the New York premiere of Guys And Dolls. Jimmy stayed behind. The just-arrived children needed a parent with them. Besides, he had the house to sell. And the furniture with it.

Up the hill one day came a Texan, feminine. He showed her around. “I want it,” she said.

“I want so-much for it,” said he.

“I can’t possibly go that high.”

“Swell,” said Granger, on whose British tongue American slang still sounds strange to American ears, though not to his own. “Because I don’t want to sell it!”

Foiled on that front, she attacked from another. “Your cat seems to have scratched the furniture. It’s shabby.”

He went lordly on her. “Madame, if the furniture weren’t shabby, it would cost you twenty-five thousand more. Do you want it or don’t you?”

Even a Texan knows when she’s stymied. Out came the checkbook. Jimmy phoned Jean on a note of elation. “I’ve sold the house and all the beautiful furniture.”

From three thousand miles away came an audible gulp. “Oh,” she said. Hardly what he’d expected, but understandable. After all, the house had spelled happiness to them both and the end of anything strikes a melancholy chord in spite of yourself. “When you get back, we’ll take a trip to Switzerland. We’ll have a look-round for the right house and the right school for the children and everything will be fine.”

“Yes,” she said, sounding flatter than ever. Well, the poor dear was tired. Premiéres, with their attendant publicity, can be as exhausting as they’re exciting. But one thing he couldn’t understand. Why was his true love crawling back to him by train instead of flying as usual?

Arguing inside

On her return the mystery solved itself. He unfolded plans. She listened in silence, her silence louder than words if you know Jean as her husband does. “She never argues. Not the way other people do. She has her own way. If I say, ‘We’ll do this,’ and Jean says, ‘Good,’ then it’s good. If she says nothing at all, it’s no good. It means she’s arguing away like mad inside.”

That evening the more he talked, the more argumentative her silence. It stopped him cold. “All right, what’s the matter?”

“I can’t stand flying.”

“Since when?”

“Since this last flight east. I never really liked it but I didn’t loathe it till now. It was rough, Jimmy. I was terrified the whole time. It’s not worth being that frightened for the sake of flying. I’ll never fly again as long as I live.”

This revelation rocked Jimmy momentarily and knocked the props out of Switzerland for good. “The whole joy of it was, you could nip in and out at will. But suddenly your wife can’t abide planes, and you see yourself living your life entirely surrounded by mountains, which wasn’t the idea. On the other hand, you’ve got to get out of your house within two weeks, so what happens now? ‘I don’t know,’ says Jean, and does a bit of a weep. I make clucking noises. Next day starts a fantastic, hysterical househunt, with fourteen agents working for us. Meantime we require shelter, so we rent a place in Palm Springs, beginning December 10th. In Palm Springs we’ll have two lovely months of sunshine and peace. And fourteen agents should be able to find us a house.”

Their business manager found it in less than two weeks, and talked in riddles. “You mustn’t buy it, it’s far too expensive for you, but I’d like you to see it.”

“What for, if we can’t buy it?”

“Because it’s so beautiful.”

When the same bug bites the Grangers, a chemical reaction sets in. They call it perking. Already they’d seen a number of houses. Nice houses. Irreproachable houses. “Lovely,” said Jean. “Delightful,” said Jimmy. They’d look at each other and nothing happened. They didn’t want it.

The house in Bel-Air, designed by Allan Siple, proved another story. One glimpse of the outside, with its happy marriage of wood and mellow red brick, lifted their hearts. Inside,two warm and gracious high-ceilinged rooms formed the living area with just enough glass to balance enough burnished wood. By the time they’d inspected the sleeping quarters upstairs and a self-contained suite for the children on the other side, they were perking on all cylinders. Jean began figuring where she could put this and that. Jimmy began figuring how many pictures they’d have to make to cover the cost. The owner said little. They felt for her. They realized how it must hurt to part with this gem.

Back in the car Jimmy was first to speak. “What should we offer?

“You can’t afford it,” said the manager, Waiting to be coaxed. Jean’s green eyes coaxed him. “All right. Better a house you can’t afford with a good resale value than one you can aftord that nobody wants.”

They signed the escrow papers a few days later and discovered that a single misstep might have been fatal. The about-to-be-ex-owner smiled up at them, albeit sadly, “Had you found one fault with that house, I wouldn’t have sold it to you.”

Man proposes

Now for two carefree months at Palm Springs. Man proposes and the studio disposes. Three carefree days, and a call from MGM punctured the peace. Added scenes for Bhowani Junction would require Mr. Granger to fly to London on the 29th. Let him take it from there.

“I blow. I know I’m going. I know I have no choice. That’s why I blow. Two days more, and we come full circle with a call from Fox. Jean’s got to start Hilda Crane right after Christmas. Our holiday’s shot. We keep trekking into town for confabs and fittings. Jean looks doleful. She likes me around when she’s working, because then she can tell me how clever she was and how everybody loves her. For the literal-minded, this should be labeled a jest. Consider it so labeled. The fact of the matter is that I’m likely to get home from the studio, feeling low. ‘I was awful,’ I groan. To lift the gloom, she cocks her head like a cheeky sparrow. ‘I was rather good.’ Which makes me laugh, which is why she does it. Apart from which foolery, of course she wants me around. To coddle and make a fuss over her. That’s her right. Coming back to nothing after a tough day’s work is neither her idea of fun nor mine.”

A dog with two tails

Before he took off on Friday, the 29th, Jean let fall the suspicion that she might be pregnant. But casually and without too much conviction, since earlier suspicions had proven groundless. Nevertheless, she went to the doctor on Saturday and gave him a piece of priceless information. “On the way here I saw a dog with two tails.”

“You’re sure of that?”

“I could swear it.”

“We’ll make the test,” he said gravely, “though we don’t really need it. If you saw a dog with two tails, you’re pregnant.”

To Jimmy in London, on the last day of the year, a cable was delivered. “Wonderful news. You’re going to be a father!”

He stood staring. at it. “Stupidly,” he insists. “Thinking wonderful and again wonderful and how are we ever going to pay for the house?”

This is pure Grangerese. Translated, means that his head was knocking the stars but heaven forbid that his heart show up on his sleeve. He got Jean on the phone. He talked to the children.

“Jean told us first,” cried Lindsay.

“Being rather excited,” Jamie reported, “we socked her down on the floor and trampled her. But don’t worry, Dad. We’ll treat her very gently from now on.”

Dad mopped a suddenly damp brow. “See that you do!”

Two weeks later he was thankful to be flying home, so he could take the job over himself. No more separations. It was sufficiently outrageous that he shouldn’t have been with his wife when she learned about the baby. His plane landed three hours late. Jean seemed rather subdued. Apprehension clutched him. “What’s wrong?”

“I’m leaving for Reno at 6 tomorrow morning.” She patted his hand. “Not for a divorce, darling. Just on location.”

And now . . .

Hilda Crane’s finished now. Granger’s next film isn’t set. While he was in London and Jean at work, their secretary moved them into the new house.

They live quietly as always. Under the serene surface, however, you can’t but be conscious of an inner ferment, controlled yet apparent, focussed on a day in late August or early September. Call it waiting for baby. Or babies, as far as Lindsay and Jamie are concerned. Their initial plea granted, they’ve doubled their order. “We’d like twins. One apiece.”

“Make it triplets,” advises Jimmy. “Then at least we can have all the godparents we want.” They want three sets—the Bert Allenbergs, the Cary Grants, the Sam Zimbalists.

Thus, in spite of himself, Granger breaks his rule not to make plans. But only where he feels strongly. He feels strongly on the subject of nurses. “There will be a nanny. But she will be paid by us to do certain chores. So often the child turns for advice, comfort and warmth to the nanny, not to the parents. Then what are parents for? To provide food and shelter, to say good night and good morning? That way lies disaster. The child will know that it is ours. So will the nanny.”

For the most part, however, he’s taking it day by day, grateful for Jean’s wellbeing and good sense. She follows doctor’s orders, she’s not gaining too much weight, she does as the book says.

“With a couple of minor and forgivable lapses. Women are supposed to have these strange desires. Like larks’ tongues out of season. My wife’s desires are less ethereal.”

In the book it says you mustn’t eat fried foods. Jean adores fried bread. One morning she opened her eyes, sniffing. “I can smell fried bread.”

“You can smell nothing of the sort.”

She beamed hopefully. “I know. You’re going to surprise me.”

“I’m surprising you by giving you no fried bread.”

Next morning she awoke with the same plaintive cry, and the next. He marched himself to the kitchen. He fried bread. He took it to Jean. He stuffed her so full that she hasn’t been able to endure it since.

On another occasion she craved sausage and had some for breakfast. Also for lunch. “Not for dinner, too?” he gasped.

“I wonder what it means?” she mused, eating placidly away. “D’you suppose we’re going to have a little pig?”

Those young monkeys

Though he still sneaks into the kitchen when the mood’s on him, Jimmy’s no longer chef. Cooking for four becomes a complicated business, especially when the youngsters dine at 6 and their elders later. Otherwise, the household runs pretty well as it used to. Jamie and Lindsay, mannerly kids, don’t take over. They don’t, in their father’s phrase, “glump in and turn on TV, unless we’re prepared to watch it, too. I’m no believer in the school of total self-sacrifice, which stultifies the adult and smothers the child. In a few years they’ll be living lives of their own. We hope they’ll always want us in their lives, as we’ll want them in ours. To achieve that end, you hang on to your identity. Else you wind up a dreary millstone round your child’s neck.”

The principal change in their pattern is an inward one. “In the old days we shut that door on top of the hill and thought we were supremely happy all by ourselves.

“Yet somehow we’re happier now. Without those young monkeys and the funny little things they do, the place would seem quite empty. Unfunny things as well. Jamie fell ill not long ago, really ill with a fever of 104. When you’ve nursed a child through the night, when you’ve seen him utterly helpless and dependent on you—well, I don’t propose to flounder in sentiment, but something happens—”

“What happens,” said Jean, “is simple. It’s just nice to have them.”

In short, they’re the source not only of new warmth round the house, but of new laughter. Like most fathers of daughters, Granger’s already turning a jaundiced eye on Lindsay’s suitors-to-be. “I suspect she’s going to like all the ones I don’t like. The solid specimens I approve of she’ll blithely ignore. About Jamie I’m less concerned. He’s picked his first girl and she’s an absolute duck.”

He rose and moved to the window. Outside, the gardener was still at work on the elm. Granger’s face brightened. “You know, that tree’s going to be all right.”

We think everything will be. The transplanted tree. The transplanted children. The baby to come. Cherished by Jean and the boss, how can they miss?

THE END

—BY IDA ZEITLIN

It is a quote. MODERN SCREEN MAGAZINE JULY 1956