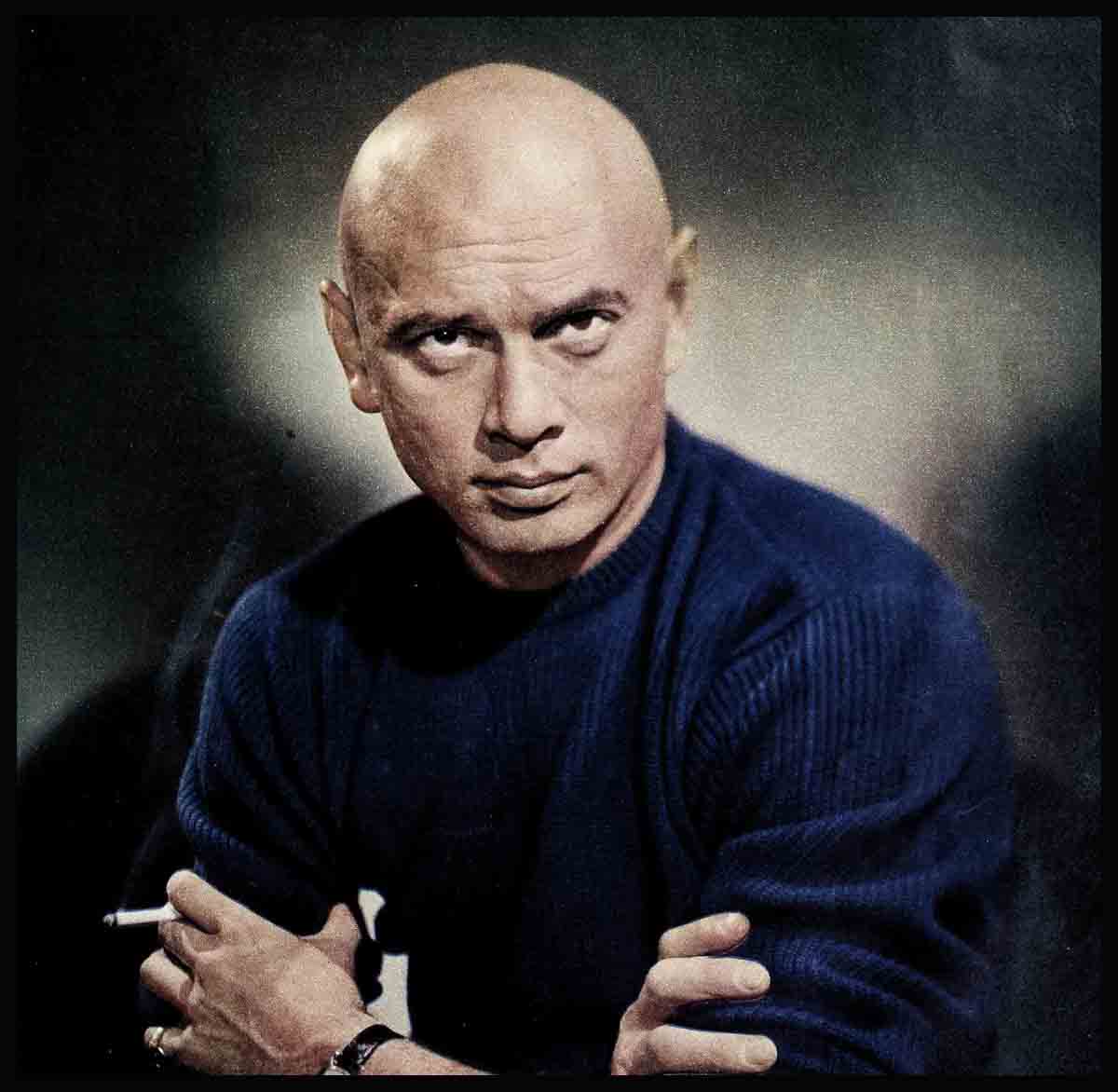

The King And Me—Yul Brynner

One hot summer night in August, 1952, I appeared backstage of the theater where the stage version of “The King and I” was playing. For more than a year I had been acting as understudy for the boy who was playing the part of the Crown Prince but I had never had a chance to go on for him. Now he was leaving for his vacation and I was taking over his role for the first time that night.

Despite the fact that this was my big opportunity—or maybe because of it—I was scared. For one thing, I was only thirteen years old and had been in only one production before. For another, I would be playing with Yul Brynner, and though I had never met him, there was something about the man that terrified me.

I had seen “The King and I” several times from the audience, I had watched Yul from the wings for over a year. He was so very stern as the King with his Oriental makeup, his broad, unrestrained gestures, his very loud voice, that I thought he must be that way off the stage too. I had heard he had a good sense of humor but I couldn’t believe it. I couldn’t see how anyone who played the King as ruthlessly as Yul Brunner, could have a sense of humor!

Looking back, I don’t know why I should have been so afraid of him, because there was nothing frightening in his offstage manner at all. When he came into the wings, he’d wave and nod to me just as he did to everyone else—but he’d never speak. I’m sure it was my own fault. I was so shy of him, so completely awed, that I never dared approach him, though I very much wanted to. But now that I had to play opposite him, I was more afraid of the man than ever.

To play the role of the Prince I had to wear Oriental makeup, and I didn’t know how to apply it. I knew Don Lawson, Mr. Brynner’s makeup man, and I went to him for help.

“Why don’t you ask Mr. B.?” (Don always calls Mr. Brynner this.) “Since he’s part Mongolian himself, he knows more about Oriental makeup than I do.”

I hesitated about taking the suggestion. An important actor like Mr. Brynner wouldn’t want to be bothered with such trifles as telling a thirteen-year-old kid how to put on greasepaint. But there was no one else to go to. Finally I summoned up the courage to go to Mr. Brynner’s dressing room. My knees literally shook. I waited for a long time before I knocked at his door.

“Come in,” he called. Trembling, I opened the door. When he saw me, he said, “Why, hiya, Sal. Come in, feller.”

He knew my name and I was floored. I had a very polite, apologetic speech all planned but I forgot every word I wanted to say.

“I hear you are going on tonight,” he said.

That made it easier for me to tell him why I had come.

“I don’t know how to apply Oriental makeup,” I said. “Mr. Lawson told me I could ask your help since you know more about it than he does. I want my makeup to be right.”

Immediately he rose from the bench where he was applying his own makeup. With the broad gestures he used as the King, he pointed to the seat he had just vacated. “Sit down. I’ll tell you how to put the makeup on but I won’t do it for you. You must learn to do it yourself.” He put a strong hand on my shoulder (a favorite gesture of his, I learned later) and, with a tongue-in-cheek manner, added teasingly, “Frankly, I don’t see how makeup can help you.” He laughed and I laughed, too.

He handed me a pan-stick (a form of greasepaint) and stuck a large mirror in front of me. “Put the pan-stick on and then rub it in,” he instructed. He gave me a pencil and showed me how to fix my eyes. When he didn’t like the result of my efforts, he made me take it off and do it over again. When it came to the eyebrows, he penciled them on for me himself, demonstrating exactly how he was doing it. Then he handed me a small bottle of body makeup, which he told me to apply in my own dressing room, and gave me a list of the stuff I was to buy. From now on, I was informed, I was to apply the makeup myself.

“Okay, feller,” Yul said when the fine job was finished. “Have fun!”

The next time I saw Yul Brynner was on stage that night. “Relax, kid,” he whispered.

All I remember of that performance was that his voice was so loud, so clear, and carried so far, that it made my own voice seem very small. After the show, he was the first to shake my hand. “Nice job,” he said. That was all.

During the weeks I played the part of the Crown Prince with King Yul, I got to know him well. Every night, we would meet in the wings before we went on, and he would talk to a thirteen-year-old boy as an equal. We discussed acting for one thing. Once, he presented me with a couple of books on acting. We talked a lot about water skiing, one of his favorite pastimes. When he asked me if I liked it, I told him I liked the water and knew how to swim, but didn’t know a thing about water skiing.

One night Mr. Brynner called me into his dressing room to show me some skis he had made himself. He’s wonderfully skillful with his hands. When I admired them, he said, “They’re yours.” I was so overcome by his kindness, I couldn’t find words to thank him. “Oh, beat it,” he snapped good-naturedly, waving his arms.

If you’ve seen “The King and I” either on the stage or in the movies, you’ll recall the scene at the very end where the King is dying and is giving final instructions to his son. The King lies on a divan and the two keep on whispering to each other, while other stage business is going on. To make it appear that he really was giving me final instructions before his death, the King began telling jokes one night. I felt it was my turn to tell one. It proved to be terribly corny. Yul groaned and said, “Oh, no.” Sometimes he’d repeat it to others, just to tease me and to prove to me how awful it was.

When the jokes began to pall, he started to play “knock-knock” for several evenings and it sure kept me on my toes. In the midst of my grief at seeing my “father” in his death throes, I had to think up a good “knock-knock.” It’s a wonder we ever kept sad faces.

Though at first I was completely thrown by his sense of humor, I had to use every acting trick at my command. Soon I realized there was method to his madness. This was Yul’s rather unconventional way of teaching poise and balance. It was tough to take but I learned to laugh at it, since it proved invaluable experience.

At one point during the play’s run, I was beginning to have trouble with my part. It was getting mechanical and I wasn’t getting what I thought were enough laughs. One night, I told the King about it. He might have said, “Oh, you are, too; you’re just imagining it.” He didn’t. He said, “You aren’t playing the part straight enough.” Though it wasn’t his job, he suggested that we get together and rehearse it again. Immediately, I began getting laughs.

I was very grateful to him for his frankness but there are some people who don’t like it. I’ve heard him telling others who came to him for criticism exactly what he thought was wrong. It was easy to see he had hurt their feelings.

I’d heard that he has a terrible temper, but I never saw evidences of it. Maybe he got the reputation by being so frank and direct in his criticism when he was asked for it, and from the habit he has of stamping his feet and using broad gestures when he’s emphasizing a point.

His bluntness takes many forms. If you tell him a joke which he likes, he laughs uproariously. If you tell him one he doesn’t like, he tells you it’s awful.” If he doesn’t like you, he simply tries to avoid you. If he likes you, he goes all out for you. He liked all the kids in the cast. On holidays, he had lovely gifts for all of us, and presented them with as little show as possible. He remembered all of our birthdays and dutifully ate the cake provided, even when he didn’t feel like having it. I think deep down he’s sentimental and his bluntness is a weapon he uses to cover it up.

One day he gave me the thrill of my life in such a direct way that I was completely floored. Out of the blue, without any hints or preparation, he said to me, “I’d like you to come up to our place in Connecticut for the weekend. You’ve or skis. I’ll teach you how to water-ski.

At first I thought he was joking. When I realized he meant it, I was bowled over. Imagine how a thirteen-year-old kid feels when a great star of a hit show invites him to his home! “What would you rather do?” Yul asked. “Come up with me after the Saturday night performance and stay overnight, or take the train up on Sunday and have me meet you at the station?”

There was no doubt in my mind as to what I’d rather do. I wanted to go up on Saturday night.

“Suppose we call your mother,” Yul said, “and see what she thinks about it.”

My mother was as floored as I had been. “He may stay overnight,” she told Mr. Brynner, “if it won’t put you out too much.”

Yul roared. “Put me out? We’ve got about forty bedrooms there.” I guess there must really have been six or seven.

I went around in a happy daze, grinning from ear to ear, feeling terribly important, not daring to say a word about it to the other kids in the cast, who hadn’t been invited yet. Their turn was coming later, I learned.

I think Yul’s friends are the best proof that there’s no chi-chi about him. After the Saturday night performance, Yul drove a carful of guests up to the Connecticut house he had rented for the summer. His friends, as varied and fascinating as he is, are another reliable clue to the kind of person he is. Among those with us were Don Lawson, Mrs. Lawson, an artist friend and a private detective. They’d all known Yul for years—long before he became famous. Once you’re Yul Brynner’s friend, no matter who or what you are, the friendship lasts forever.

It was about midnight when we arrived. Mrs. Brynner had already retired for the night, so Yul got to work scrambling eggs for all of us.

The next morning at six o’clock, Don wakened me by knocking at my door, and asking me to let him in. When I did, he suggested that I get into my bathing trunks. “We’re going skiing after breakfast,” he told me.

The weather was wonderful. A huge breakfast was served out-of-doors on a patio. The other guests were already assembled out there. So were the host, dressed in denims and blue shirt, and Mrs. Brynner, whom I met for the first time. She shook hands with me and asked, “Would you like to call your mother?”

If you want to know what Yul Brynner is really like, you have to see him on water-skis. He loves the sport intensely and is wonderful at it. It relaxes him completely. Not only can he ski forwards, but backwards too, and he doesn’t know the meaning of the word “fear.” He’s the sort that can take it. While he was skiing along, he suddenly fell into the water. One of the skis hit him across his cheekbone, making a nasty cut. He excused himself, drove himself to a doctor, got a couple of stitches in his cheek, and came right back to continue where he left off. He never even mentioned the accident, and made so light of it when we showed concern, that soon it was forgotten.

Though he loves to water-ski and spends hours at it, he took time out to teach me. Perfectionist that he is in everything he undertakes, he stayed with me, patiently coaching until he felt I had caught on to it. All the while he watched me carefully to see that I wouldn’t get hurt. He was so afraid that I might get hurt that he kept the motorboat going at a very slow pace. I remember yelling to him, “Faster, faster.”

Mrs. Brynner, too, is a rugged, healthy, sports-loving person with a swell sense of humor. There was no outward show of affection between them, but you had to see the way they looked at each other and laughed together, to know there’s real rapport between them. I never did get to know her well but I had the feeling that she understands her husband very well. I guess she felt we were his guests and that she’d be in the way if she hung around us.

I saw a great deal of their son Rocky, who was seven years old at the time. Yul takes real delight in the boy, who is the spit and image of him. But, though his father loves him devotedly, he doesn’t spoil him.

“I want him to be rough and tough,” he said. Yet he won’t subject the boy to anything he feels he cannot do. While I was their guest, I heard Rocky say he wanted to water-ski, too. Yul wouldn’t let him and said so in no uncertain terms. But he didn’t want to let him down completely so he carried the little boy in his arms while he skied, to give him the feel of the skis. “He’s too young to ski yet,” his father said.

After dinner, we sat around the garden. Next to water-skiing, Yul loves photography, and he took what seemed like a million shots of us. Later in the week, he took pleasure in showing them to me.

We went back to New York on Monday afternoon. It was the most delightful weekend I had ever spent but I never dreamed I would be asked again. To my amazement, Yul commented, “You need another lesson in water-skiing. Come out with me again next Saturday night.”

The guests were the same, but the weather wasn’t. It rained practically all the time. We spent most of our time in the basement, where Yul makes and keeps his water skis. Patiently, he showed me how to make them, and how to wax them.

When the boy whose place I’d taken as the Crown Prince in “The King and I” came back from vacation, I left the cast. But it was by no means the end of my association with Yul Brynner.

You probably know that he’s a wonderful director as well as a fine actor. When I heard that he had been assigned to direct a television script for “Omnibus,” in which I was to appear as a Mexican bullfighter, I was delighted. Yul, as a director, gives the actor a feeling of security. You just know you’re going to be good if he’s guiding you.

It was typical of him not to compliment an actor while he was directing him. Once, after rehearsing a scene in which I thought I had done a darned good job, he said coolly, “It’s good.” After the show was over, he told me I was wonderful. Thanks to his direction, I received many compliments on my performance.

Our friendship became stronger. Even my family got into the act. Once, while I was still in “The King and I,” I happened to mention to Mr. Brynner that my father, who is a carpenter by profession and who now makes coffins by hand, could supply the wood for his skis. Yul immediaitely accepted the offer. So Dad used to deliver the wood backstage and chat with

Mr. Brynner about carpentry. Yul liked to make cracks about my father’s coffin-making prowess, which seemed to strike him as being very funny. “Fahnstahstic!” he would say, a favorite word.

Some months after “The King and I” closed, Yul went to Hollywood, and later I, too, was signed to do a picture. We telephoned each other to try to make a date to go water-skiing together but somehow we were both so busy we could never arrange it.

Then we both happened to be in the East. My mother, who is an excellent cook and an expert on Italian dishes, thought Yul might like to sample some. He accepted her invitation with pleasure but, unfortunately, he was called back to Hollywood that very day to make another picture and he couldn’t keep the date. He called to explain the situation to my mother and apologized profusely. “But I’ll take a rain check,” he noted.

I was thrilled to learn that Yul had won an Oscar for his role in “Anastasia.” It didn’t surprise me, because I always felt he would be very big some day. I sent him a telegram of congratulations. He acknowledged it by sending me an enlargement of one of the snapshots he had taken of me backstage. While he was visiting Mexico, he sent me a postal card. All he had written on it was “knock-knock.” It was unsigned, but there was no doubt as to who had sent it.

Yul Brynner is my idol. I admit it unashamedly. He taught me technique; he taught me how to play comedy and how to listen. I’ve tried to apply what he taught me, when making my two most recent films, “Dino,” for Allied Artists, and “The Young Don’t Cry,” for Columbia. Above all, he taught me that you can be a big star and a human being.

—By Sal Mineo

THE END

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE OCTOBER 1957