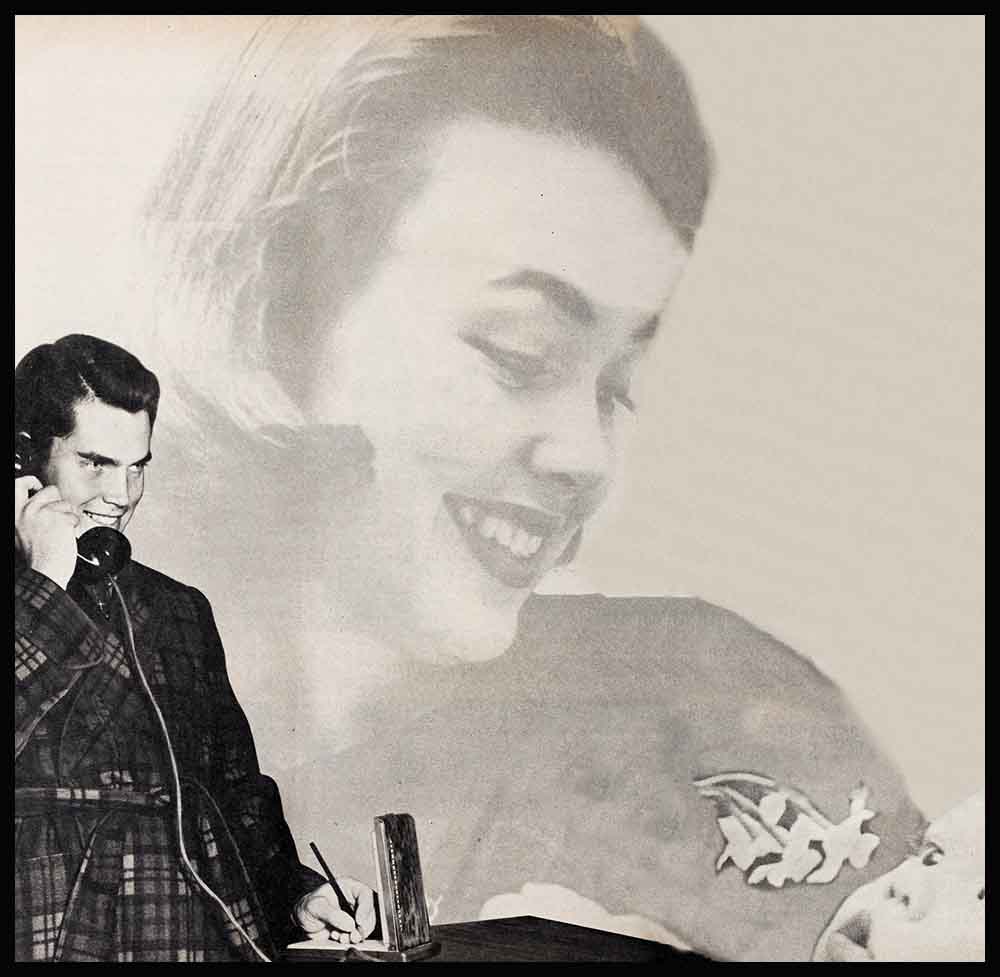

“Darling, Wish You Were Here . . .”

Jeff Hunter received the news with what is known inadequately as “mixed emotions.” Twentieth Century-Fox had cast him in the starring male role of “Sailor of the King,” an adventure yarn to be shot in London and on the island of Malta over a four-month period. It meant star billing after six years of preparation, prayer, and hard work. It was the break for which any other young hopeful at the studio would have given an inconspicuous tooth.

Yet there stood Mr. Hunter with laurels on his brow and a lump in his throat. He was about to become a father for the first time. If he left Los Angeles as scheduled, he wouldn’t catch so much as a glimpse of the stork’s approaching shadow.

That was one dilemma. Another was that Jeff and Barbara Rush had filed a sheaf of bright dreams marked “for future use.” Among them was the plan to complete the furnishing of the cozy Westwood Village apartment into which they had moved as bride and groom. They liked to shop together for their household equipment.

Another intention had been to rent or buy a cottage as soon as the baby was old enough to need a yard in which to play; that would require at least a year of research.

AUDIO BOOK

Or, if both careers had thrived to the benefit of the joint Hunter bank account, they might buy a lot high on a panoramic hill and build a cottage in which to place their early American furniture. There would have to be a swimming pool in a sheltered patio, of course, so a perfect site would have to be chosen. And then, with a family launched and a home established, Jeff and Barbara—as they had told one another so many times during the wonderful evenings they spent side by side before a fireplace in which bright flames snapped gay fingers in approval, they would make the grand tour of Europe: Paris and the Champs Elysees, Rome and St. Peter’s, Venice and the quaint glass shops, England and the Shakespeare country.

With a touch of golden luck, they said, they might be cast in the same picture, turning another dream into reality.

All this ran through the confused head of Jeff Hunter when he heard about “Sailor of the King.”

What would you have done?

If you were as wise as Jeff and Barbara, you would have done exactly what Jeff did. He asked the studio for a slight delay in departure date and was accommodated with an extra week. He began to send up smoke signals to the stork reading, “I’m not a bird watcher by hobby, but I’m really looking for you.” Finally, he made plans to send Europe to Barbara, since he couldn’t take Barbara to Europe on this trip. He bought a carton of film for his camera, he studied histories and guide books, he marked passages of interest. Barbara, who speaks French rather well, coached her husband in a few useful phrases.

The stork received Jeff’s message and proved to be indulgent. Just five days before final deadline, Christopher Merrill McKinnies (Jeff’s legal name, as you probably know, is Henry H. McKinnies, Jr., and he is called Hank by his family and close friends) came bounding into the world. He was a beautiful baby weighing eight pounds.

“Now there’s nothing to worry about,” Barbara said as she kissed her husband goodbye. “I’m fine, the baby’s fine. You’re all set to go to work with a free mind. No more worrying.”

Before he took off from New York, he phoned. “ I’ll remember everything,” he told Barbara. “And I’ll make plenty of notes so you and I can repeat this adventure step by step! And don’t you worry about me,” he said. “Everything is fine.”

This was only partly true. Jeff had the scare of one man’s life when the London-bound plane developed engine trouble shortly after it had taken off from Gander, Newfoundland, headed into the trackless skies above the steel-gray Atlantic. The pilot swung around and returned to Gander where, nine hours later, it was believed that essential engine repairs had been completed.

Jeff cabled Barbara to explain the delay, which was a good thing because Jeff’s mother (in Milwaukee) waited two hours after the plane was to have arrived in London, then telephoned Barbara in Hollywood to ask whether all was well.

Little did either of the waiting women realize that when the plane was finally taxied out for take-off, the pilot didn’t like the sound of the engine and returned to the airport for further repairs.

As advertised, though, London eventually shone out of the early evening rain and mist, the steady lights of city traffic moving busily in the wrong direction. Jeff wrote to Barbara: “Dearest Barby: You and I will descend on London at this same hour, some evening, and you’ll say—just as I thought—‘But everything is flowing against the tide.’ We’ll see the great gray snake of the Thames curled under its storied bridges, and you’ll say, ‘See, it isn’t falling down, no matter what we used to sing about London Bridge when we were children.’ ”

Jeff was met by Twentieth’s British representatives and whisked from airport to town with one stop—at a pub to give Jeff his first glimpse of one of England’s most famous institutions.

It was here that Jeff spotted an object that excited his covetousness. It was, he wrote to Barbara that night, entirely unique. “Exactly the sort of conversation piece we’ll need for the den we’re going to have in our house some day.”

This affair consisted of a solid brass box about ten inches long, six inches wide, and five inches deep. The top lid was divided into two sections. In one section there was a coin slit large enough to take a copper English penny (about the size of our half-dollar). In order to work the mechanism, one deposited two pennies, pushed a plunger which in turn unlocked and opened the second lid section. In days gone by, this was used in pubs as a cigar dispenser, a portable forerunner of today’s American cigarette vending machines.

“I don’t know how to go about getting one of these gadgets for us, but I’ll find out somehow. You’ll get a kick out of it. . . .” wrote the man who was reminded of his home by everything he saw.

He also wrote: “P. S. I’m getting better about picking up my clothes and hanging them on hangers. No more shirts over the backs of chairs. No more trousers draped over the sofa. For one thing, I think untidiness would horrify the maid in this posh hotel (yeah, ‘posh’ is the British for ‘swell’), but what is really important is that I’m trying to please you, even at a distance of six thousand miles. I don’t intend to turn our home into a seven-room clothes closet!”

Whenever possible, Jeff saw one of the plays current in London. He saw Flora Robson and Jeremy Spencer “who were terrifyingly good, even during a Saturday matinee” of “The Innocents.” He saw the Lunts in a “talky, intensely delightful” play entitled “Quadrille.” He brought his dreams for himself and Barbara up to date by writing, “I still think the time will come when you and I will be able to do a play together. Maybe it will be ‘little theatre,’ but it’s so important to us that it will have to come true. I think the Lunts have the perfect life for an acting team. Probably every husband and wife in the theatre think of the Lunt pattern wistfully, but perhaps you and I might have the luck to follow in their footsteps in a minor sort of way.”

Jeff managed to get to Paris over one weekend. He spent the hour’s flying time between London and Paris in writing another letter to Barbara.

He was met at the airport by Twentieth’s representatives. And while there was still a glint of Friday’s daylight left, he was taken by automobile from Sacre Coeur to the Place Pigalle. That evening, he went to the Folies Bergere and was awed by the magnificence of the production numbers.

He wrote to Barbara—near dawn—“Darling, Paris is incredible. Nothing one has read about it quite prepares the stranger for it. At least this is true of me, and I know it would be of you. Exciting as it is, I’d give a lot to be there in the apartment with you right now. And, honey, I wouldn’t say one single word if you had newspapers scattered from the front door to the kitchen steps. I’d be so glad to see those pages and to know that you had been reading them, and that you were in the next room checking to see how Chris was sleeping, that nothing else would matter. From now on, no kicks from me about your wading around through waves of morning news.”

On Saturday, Jeff went to the top of the Eiffel Tower . . . with the elevator acting as if it might drop, at any moment, to the bottom of the shaft like a buzzard struck by lightning.

Like all duly constituted tourists, Mr. Hunter wrote a series of cards from the observation platform. He told Barbara, “If I don’t make it down in that elevator, just remember that the view of Paris from this super crow’s nest was worth it.”

In the afternoon, having descended without incident, he visited Notre Dame Cat’hedral, strolled along the banks of the Seine, sat at a sidewalk cafe for coffee, kept in mind a plan. He asked his companion to guide him to the Rue St. Honore and a smart hat shop. “For the world’s most beautiful brunette, I want a hat that will announce ‘From Paris’ at a distance of forty feet.”

They found the hat in a window just off the famous street of fashion. For Jeff, represented love at first sight. The hat consisted of a black velvet cloche bound with black grosgrain ribbon. At the front of the cloche were three black velvet visors, each set slightly forward of the others, each bound in black grosgrain. Over this simple but elegant creation there was a small black nose veil.

Jeff wrote nothing to Barbara about she bonnet. An occasional surprise is also included in the Hunter design for living.

That night Jeff joined a group of Twentieth Century-Fox officials and visitors it an elaborate party given at The Pink Elephant, world-famed restaurant. Afterward he wrote to Barbara, “The floor show is the most amazing thing I have ever seen. Three Negroes, wearing stevedore-calypso, performed a series of savage Afro-ungle chants that would pull your hair but by the roots. I was marveling at the primitive rawness of such an act and wondering how on earth it found its way to Paris when the performers joined us at table as guests of Mr. Zanuek, who has signed them to work in Hollywood in picture. It turned out that one of the men is a lawyer, one is a doctor, the third is a successful businessman; all are French citizens of North African descent; all are gentlemen of culture who are seeking to record and perpetuate the musical forms of their forebears.”

And he added that he had a plan for Christopher: he wanted the Hunter heir know many people from many lands, to a true cosmopolite, enjoying the rich differences existing alongside of human similarities throughout the world.

“Of course I want our boy to attend Northwestern University, just as I did, and I want him to be a Phi Delt like me. Then I want him to travel before he on a career. I hope we’ll be able to take it possible for him, but if we can’t the tickets, I hope he’ll have guts though to do it on his own and work his around the world.”

As soon as Jeff returned to London, he some French linguaphone records started to bone up. He told Barbara glad he was that she had already the language. “Because when I get home you and I are going to become students in earnest. We’ll spend en tire evenings during which we won’t allow ourselves to speak to one another except in French. It’s a fascinating language; it floats over the ear like music.”

From London, the production company of “Sailor of the King” flew to Malta, Mediterranean base of the British fleet.. Jeff, who had read about the valor of Malta’s resistance during World War II, was excited about living on the island.

His first impression from plane-approach altitude was that of descending upon a mass of solid rock. As the plane neared the landing field, the rock walls separated and tiny gardens became visible. Then narrow streets winding through storybook villages appeared to wind through a landscape drawn by a child.

Once established, Jeff wrote, “This is a spot to be visited by two people in love. The Mediterranean is as blue as an angel’s eyes, warm, and so clear that you can watch the veiled tropical fish weaving around a thousand feet below the surface.”

He spent some time spear fishing, but most of Jeff’s leisure was invested in his future. He prowled the precise little shops for household equipment and bought exquisite handmade lace luncheon sets and aprons for his mother and for Barbara’s mother, as well as for the future Hunter home—and toys for the baby.

“Isn’t it remarkable,” he inquired of Barbara, “to realize that in these days it is possible for a baby, born in California, to grow up with toys bought for him by his father in Malta?”

When the Malta sequences were finished, Jeff made a fast trip by air to Rome and Naples, then back to England where he found that he had accumulated so much merchandise for the Hunter dream house and the Hunter family he couldn’t fly home with it all without bankrupting himself.

He booked passage on the sumptuous new United States—fastest ship afloat—cabled Barbara his anticipated arrival time, and dropped onto the bed in his stateroom, exhausted.

He was still catching his breath when a gale which had gradually gained intensity for hours, slammed the mighty liner against the docks, damaging it extensively enough to postpone sailing for twenty hours.

A rough start for the trip by air, a rough finish by sea.

Barbara and Jeff had made arrangements to rendezvous in Chicago on a split-second schedule, then go on to Milwaukee for Christmas with Jeff’s parents. As it worked out, Barbara was on her plane, ready to take off from Los Angeles International Airport when her mother, baby-sitting, received the cable from Jeff announcing his late arrival in New York. Mrs. Rush had Barbara paged, gave her the news. “Just so he’s safe,” said Barbara. “We have too many plans for anything to go wrong now.”

At the last minute, no one knew at which of Chicago’s seven railway terminals Jeff would arrive. Barbara and Jeff’s parents picked out the two most logical, considering train schedules, and while Jeff’s father met one train, Jeff’s mother and Barbara met the other. Barbara’s contingent hit the jackpot.

The first thing Jeff said, after that breathless, laughing, crying kiss was, “Oh, honey, I have so much to tell you . . .”

And so, with the new year bright as a penny in their pockets, they returned to Hollywood, to Christopher. (“Good night!” said Chris’s dad. “He looks ready to check out in a football uniform right now at four months of age,” and then, with real distress, “But, Honey, he doesn’t even know me!”) and to a life in which dreams are served with the morning coffee.

But the Hunters say it in French. For French, at the moment, is being spoken in the Hunter household. One must be prepared for a trip to Paris because who knows at what moment such a plan may come true.

That’s for sure. Or as the French say, “C’est vrai.”

THE END

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE MAY 1953

AUDIO BOOK

graliontorile

11 Ağustos 2023This is very interesting, You’re a very skilled blogger. I’ve joined your feed and look forward to seeking more of your magnificent post. Also, I have shared your web site in my social networks!