Mature Mood

When the rave reviews started coming in on “Kiss of Death,” Victor Mature, who still hadn’t seen the picture, had one notable comment. “I’m in!” he said. “Now I can move to a smaller house.”

Which of course would be impossible, considering the veteran and his wife and the three dogs who are living with him in the six-room place he has now.

Vic, not overly impressed with the unfamiliar adjectives critics used, was still unprepared for the sudden gain in stature he’d achieved.

AUDIO BOOK

Otherwise he would have been better prepared the day a studious reporter rang his doorbell with a solemn pencil extended ready to let the world in on the new “matured” Mature, who had made peace with his public at last. The door opened to a loud blast of “Alexander’s Ragtime Band,” two onrushing dogs and a jitterbugging Mature who wore bathing trunks, moccasins and robe, a miracle medal his mother had just sent him and a genuinely startled look.

Usually punctilious about business appointments, Vic had completely forgotten the interview. This w as the fourteenth wedding anniversary of his ex-Coast Guard pal, Bud Evans, and his cute wife Ella, who live with him, and Vic—who has a deep reverence for matrimony—particularly fourteen years of it—was observing it with them. He was most contrite.

Although if he had known what the interviewer had in mind, he would probably have appeared bearing a spear in one hand and the Encyclopedia Britannica in the other. And justly so. For a man of Vic’s intelligence could hardly be sympathetic with the sudden discovery of a possible I.Q., or as he puts it, “Look— he can talk!” And adds grinning, “I could always talk, I just said the wrong things.”

It was on a bond tour during wartime that Vic began concentrating on making a “Kiss of Death.” He saw the handwriting on the screen in the veiled looks of people he met; the contemptuous expressions of hotel cashiers, elevator boys, the man in the barbershop. These were average American people. They didn’t like this character Mature. And it hurt. It was then that Vic pledged himself when the “big show” was over, to make pictures that would erase those looks.

By Mature’s reasoning, one can hardly plumb one’s dramatic depths from behind a Technicolor chorus of lovelies, or as a cave man wearing a bearskin rug. For once, in “Kiss of Death,” he had lines to say—and he said them; a real role to play—and he played it.

And, if you know him well, you recognize in this picture the real Vic—sans stripes of course—earthy, genuine, sensitive, a realist with sentiment, emotionally equipped to give that poignant portrayal of Nick Bianco.

Mature has always been much too modest to connect himself seriously with the star. To Vic that character on the screen is entirely apart from him, a commodity to be sold, and he has gone about merchandising that Mature as objectively as the candy bars he used to sell back in Louisville. The “hunk-of-man” wasn’t a brand he liked; he cringed every time he heard it. But, since Hollywood had started selling it. . . .

Few stars can match the determination he displayed when he landed in Hollywood with eleven cents, set up housekeeping in a tent in a family’s back yard in Pasadena and got jobs mowing lawns, walking dogs and polishing the floor of the Y.M.C.A. to help pay his tuition at the Playhouse. But from his first break as the lead in “One Million B.C.,” Mature-the-screen-star was strictly a cinema commodity to Vic.

When his first picture was premiered in Louisville, Jules Seltzer, Hal Roach publicity man, had to lock him in his hotel room to keep Vic from running off to duck making a speech. This was his home, he argued, these were people he’d ground knives for and to whom he’d sold candy. They wouldn’t sit and listen to him make any speech. “They’ll all walk out,” he said. But they applauded and remained.

Even now Vic seldom sees his rushes and gets restless watching his pictures on the screen. He saw “Kiss of Death” twice (which alone is significant of his quiet pride in it), once in a studio projection room and again at the Carthay Circle Theatre, at the insistence of a pal who wanted him to go along. During the course of the picture the last time, he ate two bags of popcorn, went out three times for a drink of water and finally fell fast asleep.

Vic got out of the Coast Guard with $800, a boat, and no place to live, and v/as bunking in his studio dressing room when opportunity knocked with the revolutionary role of the gun-toting consumptive, Doc Holliday, in “My Darling Clementine.” He will always be grateful to Darryl Zanuck and to Director John Ford for taking him that seriously.

His association with the great Irish director, which turned out so successfully, had a strange beginning, yet one typical of Ford’s probing, analytical approach and of Vic’s forthrightness. He was very flattered when the director asked him to drop by his office, but his face changed when Ford intimated immediately that he had heard much about him . . . much of it not good That Mature threw his rank on a set, for instance, that he ordered the crew around. “Mr. Ford, I may be a character,” Vic exploded, “but so help me I’ve never stepped on any human being, up or down. That’s one thing I don’t do.”

Usually even-tempered by disposition, Vic has often said, “The only people I actually dislike are those who belittle other people.”

Today, Vic speaks of Ford with exclamatory enthusiasm as “the greatest director, the greatest Irishman, the greatest human being . . .” and defends a battered green felt hat that he wears with, “It has character. . . . I stole it out of Jack Ford’s dressing room.”

Notwithstanding all of which, Vic I isn’t wearing his new professional dignity where it shows. Hollywood without Maturisms would be a dismal thought and an equally unnecessary one. Vic hasn’t taken even a wisp of the veil.

Having often stated, “I’m not exactly allergic to publicity—all I want out of life is the front cover,” he backed it up by arriving in New York on location for “Kiss of Death” wearing a huge cream-colored polo coat, a natty black Homburg hat, and carrying his old sea bag slung over his shoulder. On the same trip he signed autographs for the prisoners at Sing Sing with a flourishing, “This entitles you to a three-day pass.” And once while visiting a friend at Doctors’ Hospital, he donned an interne’s uniform and made the rounds, giving the patients a big laugh but worrying one doctor who thought a feminine patient must be having a relapse when she insisted Victor Mature had just been there feeling her pulse.

Nothing would surprise the citizens of his own community out beyond Twentieth Century-Fox studios, since the day they saw him mowing his lawn attired in tails. He had few clothes when he got out of the service, Vic explained, but he did have two pairs of tails, “and I’ve got to get the good out of them some way.”

His home is a simple bungalow distinguished from the others by a silver lame curtain fluttering in the garage window, converted to an apartment for his Coast Guard pal, a blue parasol on the roof, and an occasional pair of half-chewed shoes in the front yard, the latter being the Creative contribution of his German Shepherd, “Nicky,” who’s always making new acquaintances who ring the doorbell bearing a wounded shoe or a football and the same question, “Is this your dog?”

Making up the balance of Mature’s immediate family of evictees are Bud and Ella Evans, their cocker spaniel “Blackie” and Vic’s beloved “Genius,” the big boxer he bought with a grand gesture from Tim Holt when Tim had no place to keep him . . . and Vic was living in a dressing room.

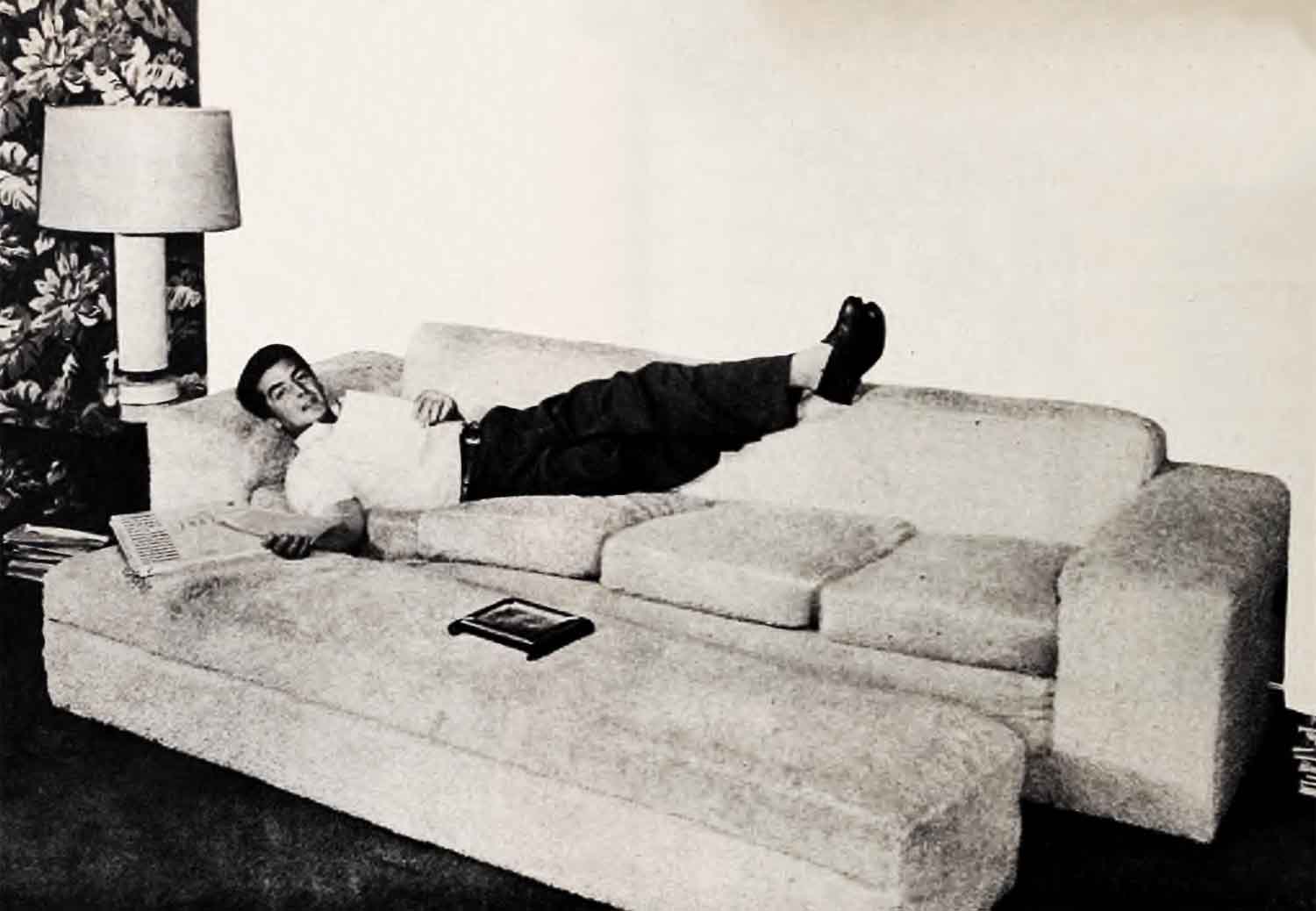

As might be expected, Vic’s home is the house of tomorrow today. Modern “Maturistic” in motif, it’s done with a large and lavish hand and with colorful charm throughout, from the den with its massive gray upholstered divans to Vic’s bedroom which features an oversize white bed and turquoise and maroon wallpaper with a Nubian slave design, which Vic says “looks loud but is really restful.”

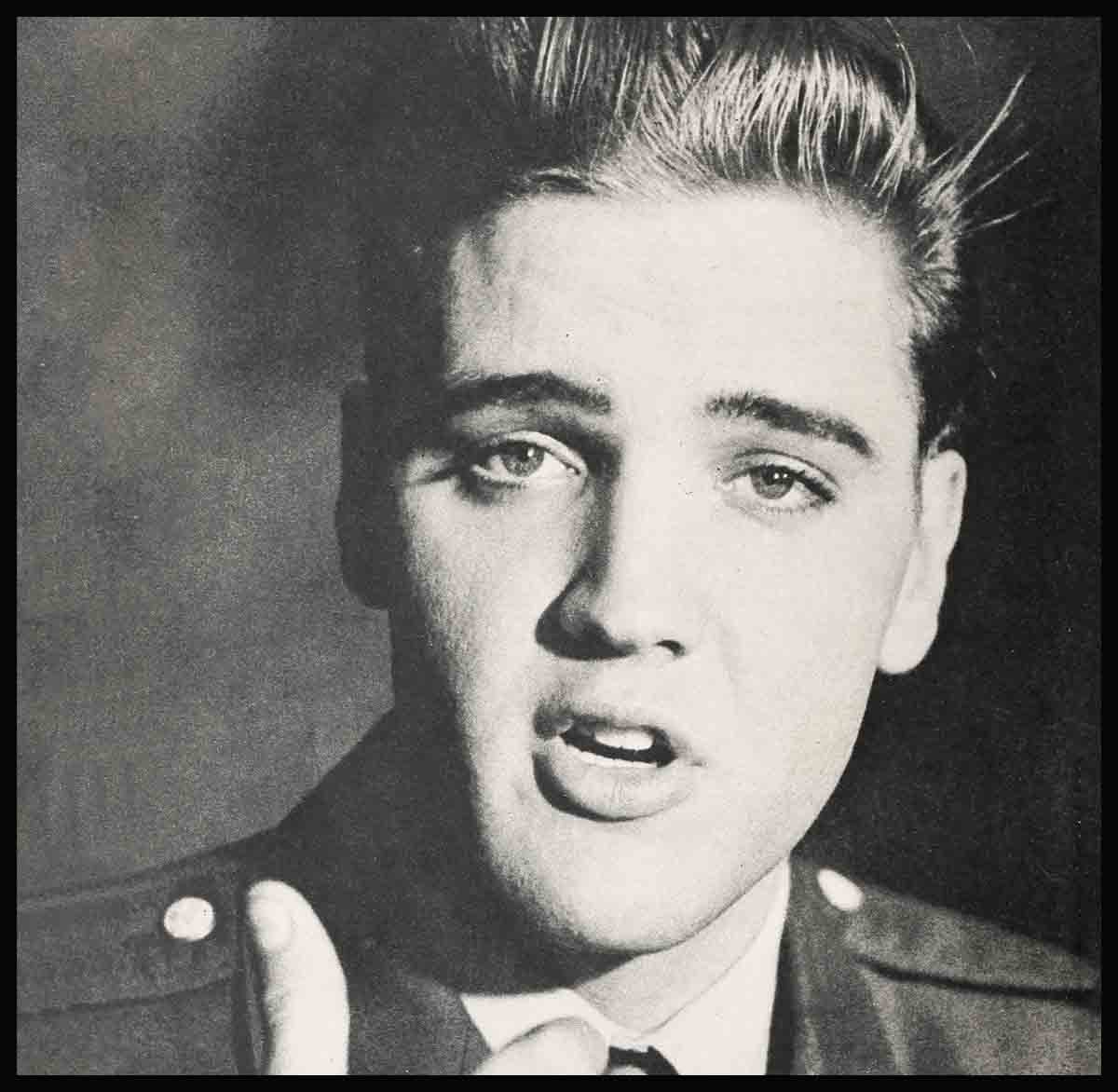

With his dark good looks, Vic is often mistaken for various extractions but calls himself “strictly a mongrel Austrian, French-Swiss, Irish, Greek and Italian, you name it.” He’s thirty-three, six feet three, weighs 220 pounds and sums himself up as the “happiest lonesome man in Hollywood,” which when you know him is an accurate description of Mature.

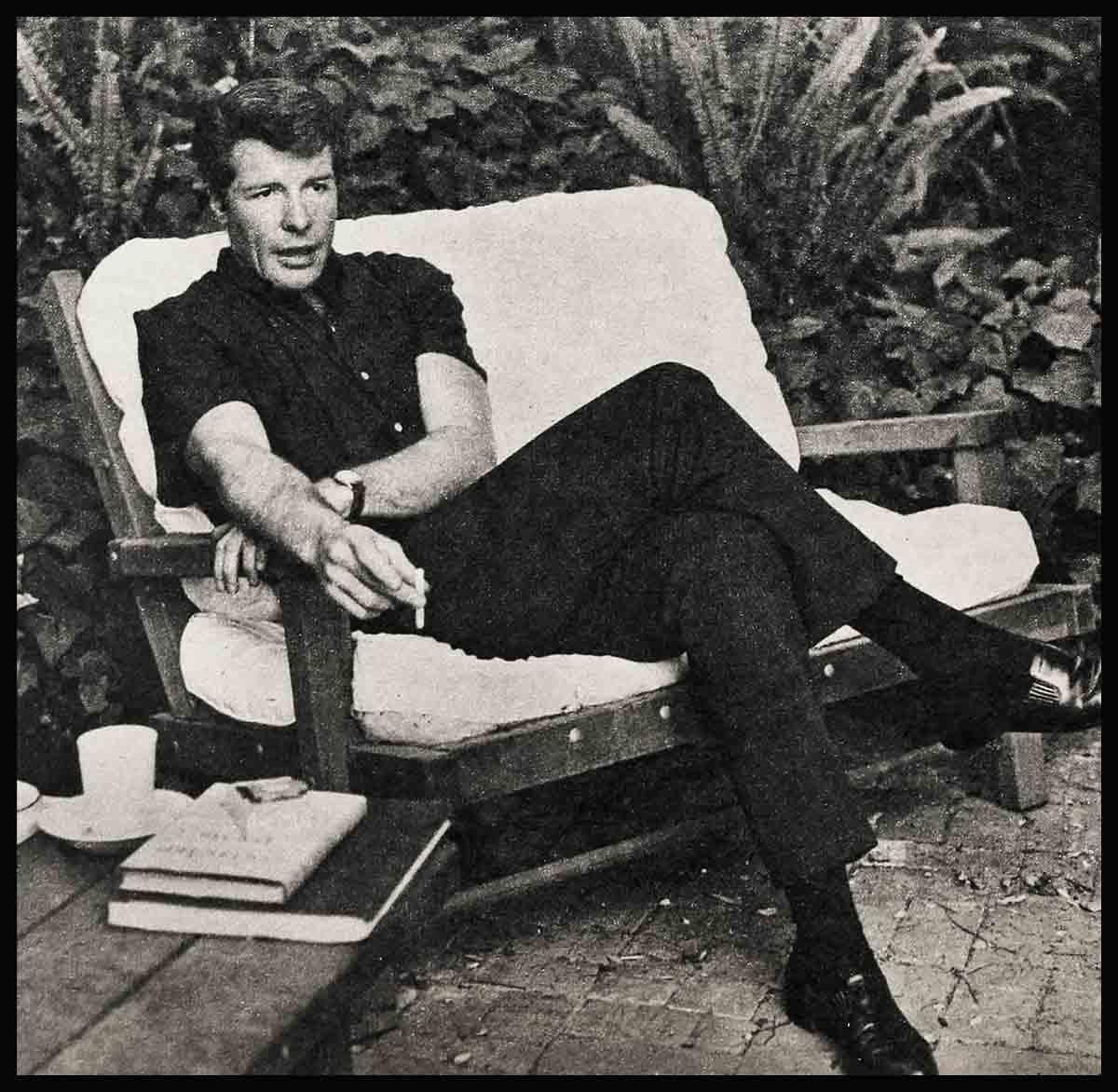

Vic doesn’t like to be alone. He’s happiest when surrounded by crowds of people and chatter, when the joint is really lumping, everybody having fun. He’s quick to sense any unhappiness in others around him, and may break loose with a spirited jitterbug solo to change their mood.

He enters any room like a friendly tornado, sweeping all present into a warm circle around him. As a host he is always concerning himself over the comfort of his guests, putting a prop under foot, moving an ash tray nearer and never letting a glass go dry.

His friends are a mixed and stimulating assortment of doctors, lawyers, publicity personnel, writers, and many ex-Servicemen, who may just watch a ball game on his new television machine or get involved in a widely divergent discussion of world economics or philosophy.

Vic’s dates number both motion picture and non-professionals, but at present he’s confusing commentators with his revived v romance with Rita Hayworth. This is causing some serious speculation among his friends, who well remember that years ago when she needed it most, Vic taught Rita to laugh again—and quit laughing himself . . . inside.

Intermittently, he fancies himself quite a gourmet. He improvises on proven recipes, makes his hot cakes with whipped cream, puts canned peaches on his baked hams instead of the more conventional pineapple, and throws everything but a leftover house guest into the seasoning tor some special sauce.

He’s equally generous with long distance telephone calls, particularly at odd hours, and his mother in Louisville, to whom Mature is deeply devoted, is never surprised to pick up the phone and hear his vigorous, “Hi Ya Sweetie,” his Standard greeting for the opposite sex, including Bud Evans’s four-year-old daughter.

From all indications there will be no more bearskin rugs or glamorous gams for Vic to hide behind, for which he thanks Darryl Zanuck, who kept his word to give him something he could really “tear into.” He has a new four-year deal without options and with a substantial raise that’s indicative of a studio quote on Vic’s future.

Henry Hathaway, noted director of “Kiss of Death,” says emphatically that rugged realism is Mature’s forte. When asked for his own serious comment on that picture, Vic is very apt to say he only regrets that the neighborhood grouch back in Louisville who’d always predicted “that Mature boy will wind up in prison some day” didn’t live to see it.

But break him down and he will admit. “It gives me such a wonderful feeling inside—such a good feeling, I can’t explain it—but you know.”

As to what the “new” Mature wants to do from now on, he says, “Anything down-to-earth. I should never do the other things, not with these sad spaniel eyes of mine and this sad droopy looking puss. At least my friends think it’s sad, he shrugs, “others just think I’m smelling something.”

And, shrug as he may, it’s the sweet smell of success, the kiss of life to a screen Vic, “matured.”

THE END

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE JANUARY 1948

AUDIO BOOK

No Comments