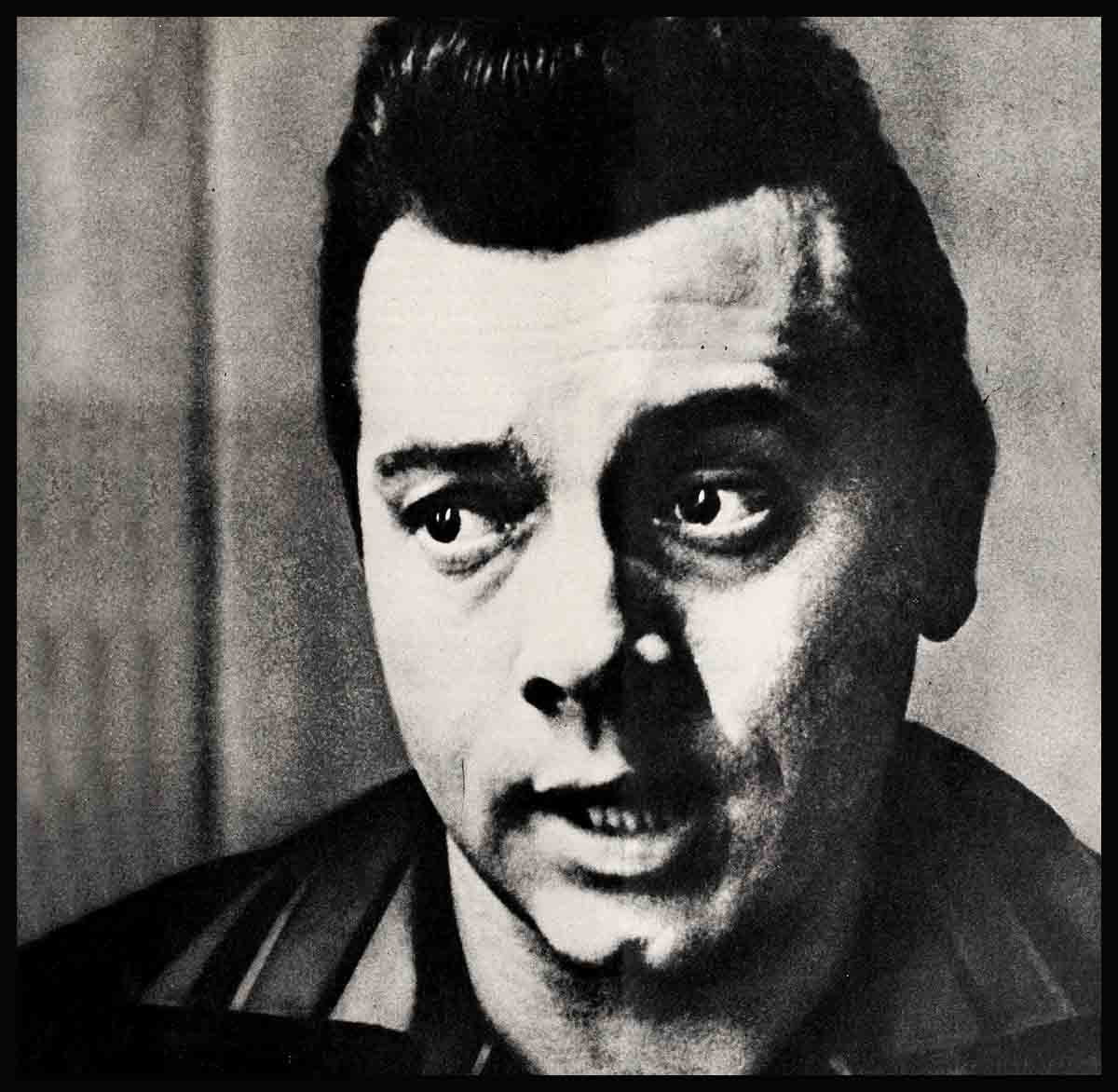

Mario Lanza Answers Back!

You’ve read many times and in many places how impossible and temperamental and big-headed Mario Lanza has become. He won’t work, he won’t report to the studio, won’t do this, won’t do that, they report. Everyone has had his say but Mario. Now here is his story.

But before I begin, I must go back several months to New Jersey, where Ray Fasano lay dying. She was ten years old. And there wasn’t much to distinguish her from thousands of other little girls except that she was suffering from an incurable disease, and she loved a movie star and he returned that love. He called her regularly; sang to her over long-distance; entertained her in Hollywood with her mother and a nurse. But she was puzzled. She read so much criticism about her idol. “Why,” she repeatedly asked him, “do people write such bad things about you?”

He could not explain; and for this child an explanation wasn’t really necessary. When Ray died, she was clutching a photograph of Mario Lanza, and it was buried with her. In Hollywood, the brawny battling tenor received the news and wept.

I write of this incident because it is pertinent to my story of Mario, who for over a year has been the mystery man of Hollywood. During that time, I’ve traveled extensively; everywhere I’ve gone people have wanted to know what was happening to Lanza. Why would he not answer the whacky stories and charges made against him? Was he having a nervous collapse? Had he gone high hat? Most of all, his fans wanted to know when Mario would sing again?

Last winter, for example, I was walking along a street in Mexico City, thinking I was incognito, when a native stopped me and said, “You’re Mario Lanza’s friend. Can’t you persuade him to return to the screen and sing for us again?” I told him I’d try.

Frankly I was puzzled too, because Mario had been a confiding friend long before he landed in pictures. He even put himself on the spot with other Hollywood reporters by publicly naming me as one of the three people responsible for his movie success. But when I thought he needed help most, he wouldn’t answer my telephone calls. I wanted to tell his side of a story that had assumed more ugly angles than a centipede has legs. I got flowers from him, yes, and notes too. But not one shred of information did he give me about his fight with Metro.

Finally I gave up. His fans didn’t. Letters asking about Lanza continued to pour into my office. The most touching came from invalids, who depend much on radio for enjoyment. They simply couldn’t understand why they were being deprived of the pleasure of hearing the Lanza program.

There were some tragic cases. A mother wrote that her small daughter had lost the use of her hands, but wouldn’t exercise them to get the strength back. So she had to resort to a heartbreaking device. The child worshipped Mario; and just before Lanza went on the air, a radio, with the volume turned down very low, was moved near her bed. To hear Lanza, the child had to use her hands to turn the dial, bringing the sound up.

Well, you can’t skip or ignore a guy with influence for good like that. Finally I got Mario on the telephone and said, “Listen you big lummox, I’m getting hundreds of letters from people who are really concerned about you. They need their faith in you reaffirmed. You owe it to them.”

That did it. “Hedda,” he said, “why don’t you come on out to my house? I’ll tell you anything you want to know.”

I didn’t waste any time in getting out to his beautiful Bel Air home. It’s on a quiet street, which is necessary because Mario’s a light sleeper. He averages about five hours of slumber a night under the best conditions. According to his wife, Betty, loss of sleep caused by traffic noises so exhausted Mario that he couldn’t start “The Student Prince” on schedule. But the new home, built on a hillside, is as quiet as a country meadow.

Upon entering the house I noticed a ribbon bearing this inscription: “The lion is dead. Long live the tiger,” and asked the meaning of it. Mario roared with laughter. “Don’t you get it?” he said. “Leo’s the lion. I’m the tiger. The ribbon came off a wreath of flowers a friend sent me the day Metro fired me—that is, to put it legally, terminated my contract.”

He led me into the living room, where Betty, his wife, and Constantine Callinicos, his accompanist and conductor, were waiting for us.

Mario was in a happy bubbly mood that veered to half-mocking anger only when a person he loathed was mentioned. His face was completely relaxed. He was overweight, but this appearance was partially an illusion. Because of his rather short height; his huge chest and broad shoulders make him look heavier than he actually is. But he has developed a pouch, and I said, “Too much red wine, my boy.”

“No, Hedda, food,” he declared. “And speaking of food . . .” As if on cue a maid entered with a huge tray of hors d’oeuvres.

“You idiot!” I screamed. “I told you I was on a diet and not to tempt me.”

“I got it all for you,” he howled, “and only the best—caviar, paté de foie gras, cheese, shrimp. Come on. Let’s live it up a little. I’m going into strict training for a concert tour. I’ll be gone eight weeks. And wouldn’t you know it? I picked July and August, the hottest months of the year.”

“Why didn’t you go to England for the Coronation?” I asked.

“T thought,” he said, “it was more important to sell myself back to my own country first. I’ve taken a lot on the chin, but I feel that I owe lots to people who’ve remained loyal to me through all this trouble. I had a fabulous offer from England—$300,000 to sing there during Coronation week. You must bear in mind that I’m not humble about myself, but also I’m very honest. I don’t believe in the malarkey of a person’s being modest about his career. I’ve spent thousands of dollars to find out how valuable I am at the boxoffice. I want to show you something.”

He left the room and returned with an armload of magazines from various countries. “I buy these every day and study them to see what my pictures are doing everywhere. If I don’t deserve what I ask for, I don’t want to lay claim to it. I’m not worth $300,000 offered to me to sing a week in England; and I told the bidder so. I took that lesson from Caruso. When he was asked to sing for several times his average salary, he always declined, saying he wasn’t worth it.

“But I do know what my pictures have done. It was flattering when Metro sued me for $13,500,000. That was what they figured that my pictures would have made during my suspension. Did you know that ‘The Great Caruso’ brought in $19,000,000 the first year of its release? I’ve got the facts; and the four pictures I’ve done took in $40,000,000. I don’t maintain that I’m the greatest star; but I’m among the first three top draws in every country.”

“Come now, let’s get down to facts. What was your trouble with Metro?” I asked.

“For a year I screamed about not wanting to do ‘Because You’re Mine,’ and delayed it as long as possible. In it I was made a little boy and something of an idiot. It was not the kind of picture to follow ‘Caruso’ and foisting it on the public wasn’t fair. I was right. Critics the world over said, ‘This is no vehicle for Lanza.’ I personally got ‘The Lord’s Prayer’ number into the film. And that I think gave it some dignity and helped save it.

“My biggest beef with Metro was that the studio wanted to be commercial, and I wanted artistic betterment. Put them together; they don’t mix. I rebelled because of my sincerity to the public and my career. I believe I’m qualified to speak. While we were making ‘Caruso,’ most of the big brass at Metro thought I had no chance of making a success with it. They said it had no exploitation value. Doing that picture was an inspiration and all through it, we worked under pressure. The picture was shot in thirty-one days. I was in all but twelve minutes of the film. If I could do that, I figured I was qualified to speak out my views. I wanted to follow ‘Caruso’ with another big artistic picture with boxoffice value. But the front office didn’t dig my angle. I was told, ‘You were successful the last time out. So just keep on being successful. Just keep doing pictures.’

“But, Hedda, of all the millions of people in the world, God gave this voice to me. Let’s say it’s not really mine. I’m just the keeper of it. And to the keeper goes the responsibility, which is not easy to shoulder. I love smoking and wine, for instance, but I had to give them up because they affected the voice. My thrill is in performing. When I sing I like to think that tired people are transported into a world of illusion, for a little while escape reality.”

I was beginning to understand Mario. I saw him as a man who would sacrifice a fortune battling the heads of a powerful studio for the sake of artistic integrity. Yet, he was the same fellow who used his God-given voice to sing, without pay, for a dying child. And for the first time I noticed that he never said “my voice.” It was always “the voice.” It was as though he considered “the voice” something apart from the man.

“Why didn’t you do ‘The Student Prince’?” I asked.

“I loved the script,” he said. “Usually one is allowed twelve to fourteen weeks for the musical recordings alone. We made them in two weeks. Most every number was done in just one ‘take.’ That had never happened before. Ask Costa.” (This is his nickname for Callinicos.)

“It was the greatest thing Mario ever did,” said Costa.

“Metro wanted to make a few bucks, and I wanted to make a good picture,” said Mario. “The worst thing that can happen to a man is that those in control of his destiny fail to believe in him. I say, ‘Take back your money, but believe in me.’ The producers used to listen to my advice. But when I became a big star, they said, ‘We’ll take the reins in on this so-and-so.’ Did you know that no technical adviser was going to be used on the picture until I got hold of Costa myself?

“Then I was asked to play the part as a Prussian. Such a character didn’t match the voice. You don’t just toss a song in a picture. You sing to what’s later going to appear on the screen. But the studio couldn’t see it that way. Call me immodest. But I felt that I was being treated cheaply when I was boxoffice Tiffany.”

“Why did you keep silent and refuse to be interviewed all this while?” I asked.

Because I had nothing to defend,” Mario said. “If I’m honest, I don’t defend. Had I made a statement, it would have confused people even further. Even now, I can’t tell the entire truth because so many things are still in litigation. Haskins and Sells, one of the best auditing firms in America, is now going over my business records. It says that they’re the most mixed-up accounts the firm’s ever seen. But what was I to say? I’ve not been tied up in any scandals. I don’t go to night clubs. Primarily I’m a family man.”

“Well, what have you been doing with your time the past year?” I asked.

“Putting together one of the greatest repertoires you’ve ever heard,” he said. “Let Costa tell you about it.”

“Most people in the operatic field sing mostly well-known numbers,” said Costa. “But in masterpieces, there are pages and pages of unknown and wonderful material. Somebody has to be interested enough to find it. You can’t buy the music, but many libraries have these selections. Mario has an instinct for looking through music and recognizing the great but unfamiliar material. Most famous singers wouldn’t dare take a chance on these numbers. But Mario, with his following, can. Wasn’t he the guy that sold an aria from ‘Aida’ to the bobby-soxers?”

“If I find something wonderful that a man has written, isn’t it my duty to present it to the public?” asked Mario. “We’ve spent a whole year putting a concert program together. The work, my children, and of course Betty, have kept me from going off my rocker during all this trouble.”

“Okay,” said I, “let me hear what you’ve done with the voice. Go on, sing.” After a mild protest, he pawed through a stack of music, selected “Call Me Fool” and “If You Were Mine”; and then with Costa at the piano cut loose as only Mario can. I was amazed. The voice was better than ever. The whole room shook with the vibrations from it.

When he had finished, Lanza turned to me, looking like a little boy faking coyness over a job well done.

“Why, you big baboon!” I exclaimed. “Your voice has the quality of Caruso’s—plus an added element, excitement.”

Mario flopped to a chair and said, “For those kind words what should I do for you? Drop dead?” Then continuing on a serious note he added, “I wanted you to hear me sing and tell my side of the story so that you would understand what I’ve been fighting for. Mannie Sachs (vice-president of RCA records) dropped by here the other day. He thought he knew me rather well, but he hadn’t heard me sing in a year. So I sang for him. The guy cried. He seemed to be at a loss for words. All he kept saying was, ‘Why, you so-and- so,’ which is cleaning it up, because Mannie never cusses. Now let’s have some pink champagne.”

“No champagne,” I said. “I thought you weren’t drinking.”

“But this is a special occasion,” he argued. “We started this thing together. Remember, way back in 1943 you were yelling about me and opera. You gave me a magnificent challenge by writing in your column that I could do ‘Caruso.’ And I did. Now we’re starting over again together. We’ve got to toast the occasion.”

I relented. We clinked glasses. Mario started playing back the score from “The Student Prince.” “These are only working records, which I was to use in helping synchronize my singing with my acting. But listen, and you’ll hear that each of them starts with ‘Take one.’ Then you’ll believe that we made all the recordings in a single try.”

He seemed to be completely familiar with every detail of the picture. Before each record, he would explain the scene, graphically and warmly, that led up to the singing. Often, as if thinking I didn’t quite believe him, he would turn to his conductor, “Wasn’t that right, Costa?” Always Costa nodded his agreement.

The music seemed to transport Mario to another world. I don’t think he cared whose voice he was listening to, so long as it was good. But the voice happened to be his own. Frequently he would point out something especially beautiful in the lyrics, or at some especially good note raise his fist to gesture subconsciously victorious achievement. Suddenly he yelled, “We’ve got caviar, champagne, friendship, music. Who needs anything else?”

His mood was infectious. We got to shouting “Bravo” and applauding each record. “Now comes a number called ‘Serenade,’” said Lanza. “Ann Blyth and I held hands while we did it. You see the boy and girl are in a boat. I sing softly at first, but I can get louder later.”

“That I can guarantee,” said I, which touched off another storm of laughter in Mario. “Girl, you do dig me!” he exclaimed. “And they wanted me to play an arrogant Prussian to this kind of music!

“Curt Bernhardt (who was to have directed the film) told me to be more restrained—less emotional. But it’s the only way I can sing,” said Mario.

“That’s the secret of Mario’s great appeal,” said Costa. “He’s a romantic, unrestrained singer. Did you ever hear a Caruso record without a sob in it? I defy you to name one.”

“You appreciate the lyrics as well as the music,” I said to Mario.

“I live by words,” he said. “A song must be a happy marriage between the lyrics and music. My job is to tell the story of the words. Caruso is a legend because he sang every word. A critic once wrote about me: ‘He sings every word as if it were his last on earth.’ And I can’t do otherwise.”

“When are you returning to pictures?” I asked.

“I’ve got to get back on the road and meet the people again first. I’ll do only two concerts a week. So I’ll have as much time to talk with reporters as they wish. This time,” he said glowering at some memory, “the press won’t be handpicked for me. I’ll talk to everybody and answer any question that I’m able to at the time.

“I’ll be back in Hollywood in September. That’s when I think everything will start popping. All of our legal trouble should be straightened out. I want to start my radio show then and get back to pictures. I love pictures because they reach the greatest number of people. I’ve been offered ‘The Vagabond King’ at Paramount; ‘Serenade’ at Warners; and another musical at Universal-International. But the concert tour comes first. I’ve got to go out and show the public what I can do. When I sell myself to live audiences, I’ll be ready to return to films.

“So far I’ve been working in silence. You have no idea how many albums of records I send out to hospitals each month. I’m going to give one concert in the memory of Ray Fasano. You spoke to her on the phone just before she died. The cute little monkey with the big brown eyes and questions that came at you as fast as machine-gun bullets. Hodgkins disease, which killed her, is a form of blood cancer. So I’m going to give the money I’ll raise at the concert to the Damon Runyon Cancer Fund in her name.”

“What about a career in opera?” I asked. “You always said that was what you were aiming for.”

“If you’ve seen Cinerama, you’ll know that its greatest scene is that done by the La Scala Opera Company. It gave me an idea. I’d like to do an opera in its entirety in that medium, using subtitles or good English translations of the lyrics so that everybody can understand the words. You could do that in Cinerama, eliminating the usual repetitions of opera.

“I think I could sell such an opera, because I’m the first classical singer who ever sold a million copies of one record—and the first singer of any type to sell a million album records. We all had the same crack at the market. Finally, I want you to understand that my quarrel has not been with artists, but with executives who try to make you perform according to their way of thinking. I can sing to people only when they believe in me. You always have; and I hope you won’t change. An artist needs the faith of his audience.”

I closed my notebook and was preparing to go when Betty said, “Hedda, you can’t leave without saying hello to our little girls. They’ve been waiting to see you.”

Colleen and Elisa, dressed primly in organdy and with red ribbons in their hair, were ushered in. Elisa, aged three, immediately went into a ballet dance. “She’s a tough one,” Mario said. “Listen to what a deep voice she has. Say, ‘Be quiet,’ to Aunt Hedda, Elisa.” The child replied. And hearing the deep voice coming from such a tiny little girl broke Mario up. She kissed her father and resumed her ballet step, whirling about the room with her hands held over her head.

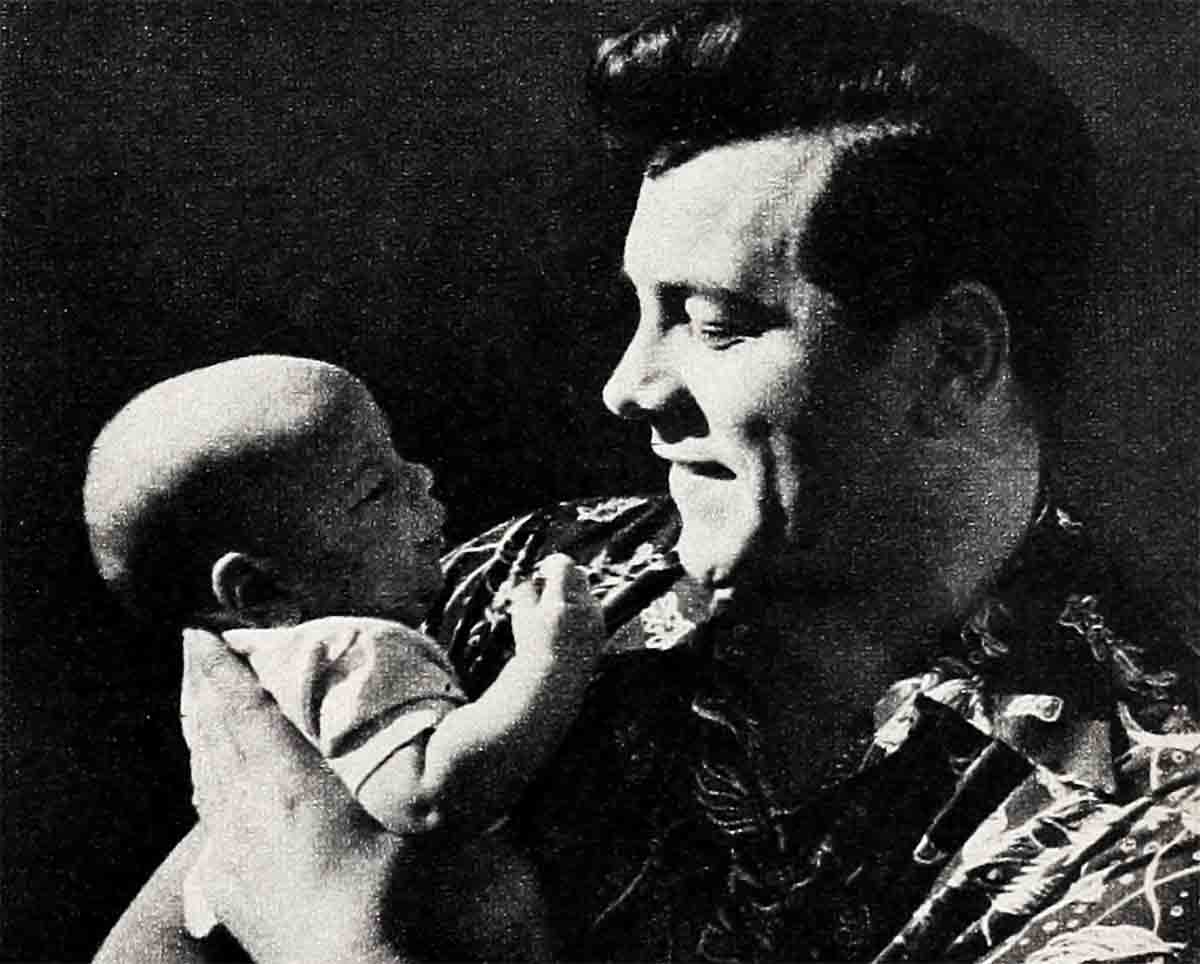

Then Betty brought in their newest, the son and heir, Damon. “He’s already wearing clothes made for two-year-olds,” said Mario proudly. “And look at that back—strong as steel. His life is already dedicated to being an executive hunter. But instead of Africa, he’ll do his hunting in Culver City.

“Now I’ve got to show you one thing more,” he continued. “Come down to the garden with me.” I followed him down a flight of steps to his gym. Weights, dumbbells and other exercise equipment were stacked everywhere. Mario ducked into the boxing ring and pointed out that the ropes were made of white velvet. “We go all the way,” he laughed.

The whole family followed me to my car. Betty was carrying the baby. The two little girls waved. The California sun was sinking low over the scene; but for all its brilliance, it was not as bright as the smile on Mario’s face. And my own heart was smiling too.

“They got him down for a spell, but didn’t lick him,” I thought. “He’ll have his turbulent moments always, because he’s a highly emotional guy; otherwise he couldn’t sing as he does. He’s learned his lessons the hard, expensive way. But he’s gained a new integrity. Hollywood will never be able to destroy him; he’ll be back bigger and better than ever.”

He puts goose flesh up and down your arms and gives a tingle to your spine when he sings, and those top notes are no longer strained. As I drove down the hill toward home, I wished that little Ray Fasano had lived to glory in his future, which I feel will be far greater than anything he’s done in the past.

THE END

—HEDDA HOPPER

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE SEPTEMBER 1953