Johnny Levels With Us About

I met John Saxon in the lobby of a New York theater, on Forty-Sixth Street west of Broadway. This interview was the first since his return from Europe, where—the press had predicted cheerily—Vicki Thal was supposed to become Mrs. John Saxon, with an idyllic honeymoon on the Continent to follow. Instead, the romance had crumbled into nothing, and John had come home alone. A disappointing ending, it seemed.

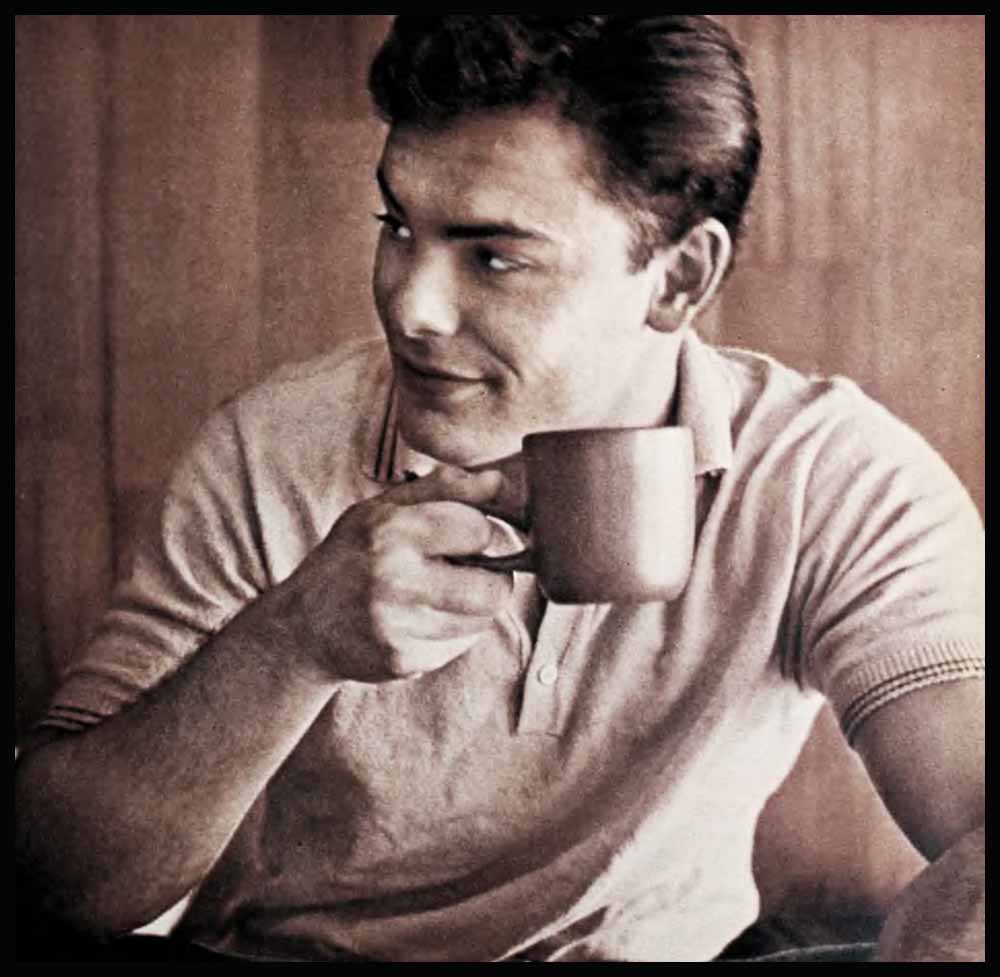

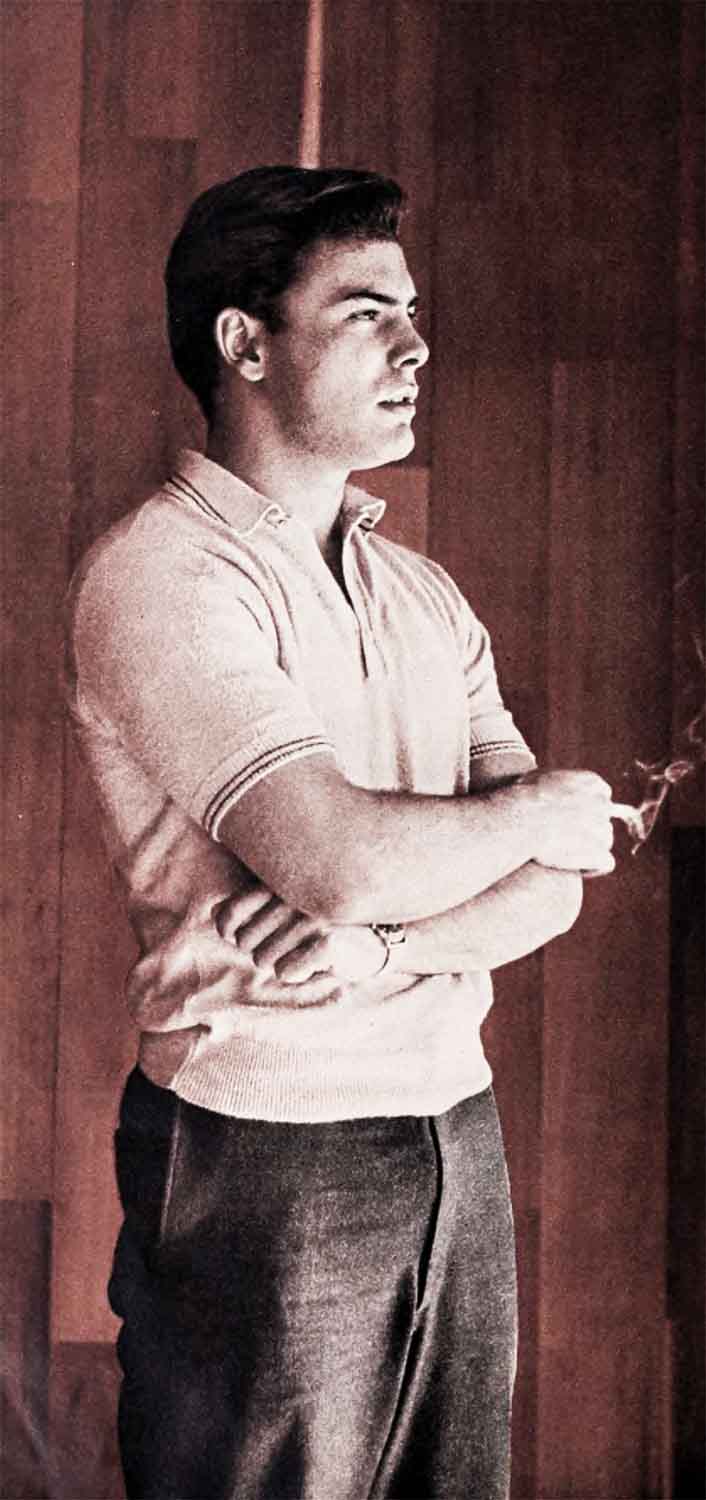

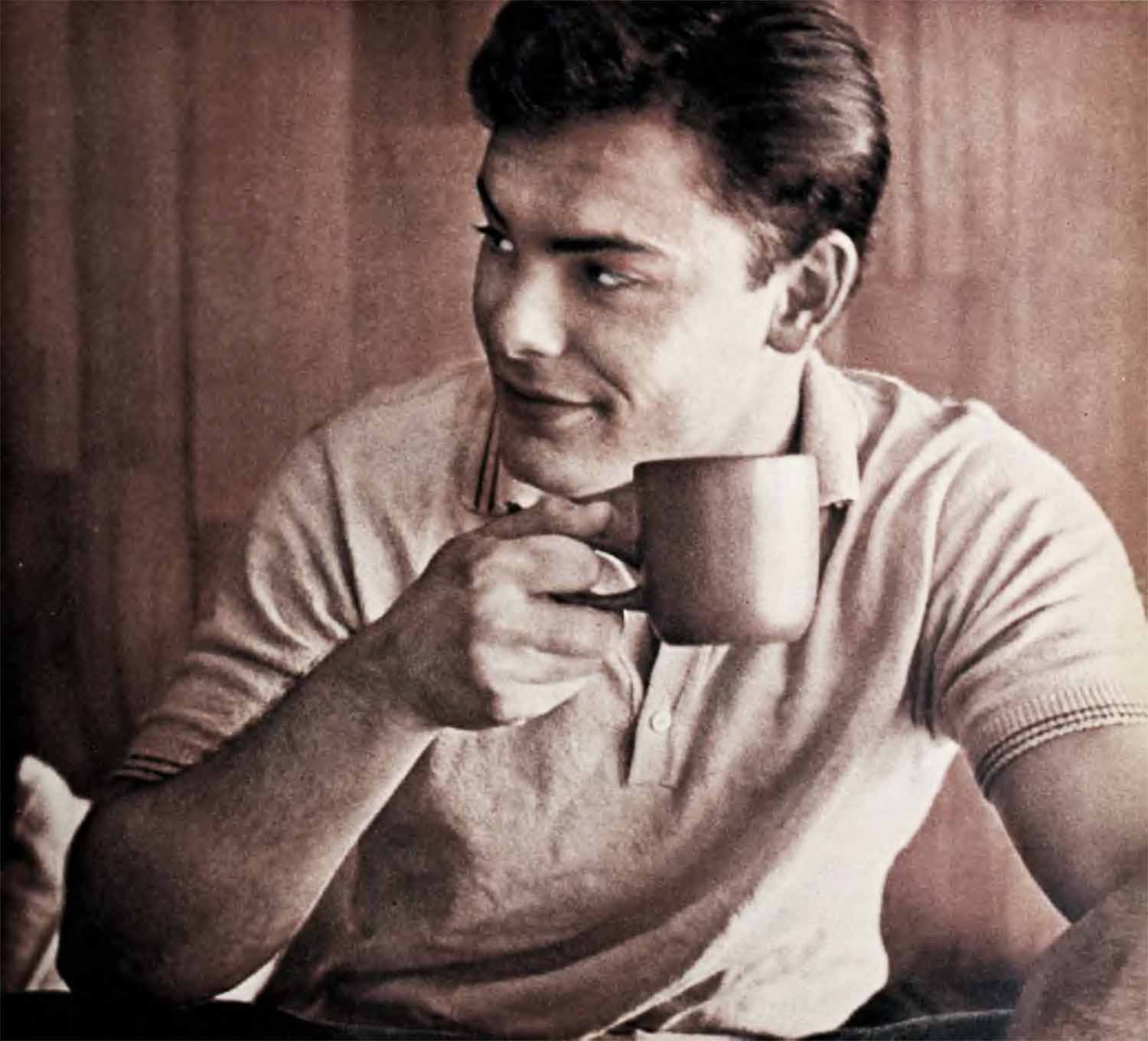

I was early; John was late. He had been absorbed in the play—Alfred Lunt and Lynn Fontanne in “The Visit”—and he was one of the last to leave the theater. He came through the doorway looking for me, lighting a cigarette. He wore a gray suit with a fine black pencil stripe, one of those new four-button jobs with hand-rolled seams and turned up cuffs. The flap of the jacket pocket was lined with a red paisley print; so were the cuffs. From above the doorway, hidden lighting picked up auburn glints in his dark hair, and his eyes shone as intensely as burning coals in an outdoor grill. People stopped to look at this young man.

Two well-dressed middle-aged women stared and whispered together—“John Saxon”—and stared again. Feeling their eyes on him, John seemed uneasy—strange reaction for a successful young movie actor.

But his face brightened as I introduced myself. “Hi!” he said, stubbing out his cigarette in the sand Container. “Let’s get out of here. The studio has a car waiting.”

He had no sooner left the theater than a chorus of shrieks rose above the taxi hoots. “It is! It is! Johnny! Johnneee!” From across the street, a group of girls darted through the crawling after-theater traffic and blocked his way to the U-I limousine. Utter panic flashed across John’s face.

The girls lined up, dancing eagerly. One of them got his autograph, then ran back to the end of the line, giggling and fumbling in her purse for another scrap of paper. When she reached the head of the line again and handed it to him, he looked at her and asked, “Didn’t I give you one before?”

“What difference does that make?” she said blandly. “Don’t you know it’s people like myself who make you a star?”

Genuinely upset, he signed the paper. “Now if you’ll excuse me,” he said. “I have to get to a radio show.” Through the car window, he waved at the fans as we inched away. When the car began moving faster, he settled back with a sigh of relief. “She’s right, I know. And I am grateful. It’s just the screaming that bothers me, that’s all . .

The car had turned east, and New York became a ghost city as it went through the deserted night-time streets of the garment district. ‘I’m glad we decided to talk in the car,” John said quietly, then lost himself in thought.

“Do you mind stopping by my house in Brooklyn?” he suddenly asked. “I don’t think it’s out of the way.”

As we drove, I asked him, “How did it feel the first time you returned to Brooklyn as John Saxon?”

John laughed quietly. “That seems like a long time ago. I was Carmen Orrico then. But I’d changed my name already. I was christened Carmine, and I guess I was thinking that Carmen Lombardo had done pretty well in show business. But ‘John Saxon’? Sometimes he seems like a stranger to me. He was born ready-made out in Hollywood, something out of somebody else’s imagination, without any background or tradition. To myself, I’m still Carmine Orrico, and he has a real, definite, solid background, all right. There it is, on the other side of the bridge.”

Brooklyn lay ahead. For a long while after Crossing the river, John was silent—not moodily, but rather alert to his surroundings. Eventually he straightened at sight of a school building and pointed. “St. Catherine’s of Alexandria,” he said.

“I guess the first day of school is a big day in everybody’s life. I certainly remember mine! I was five years old, and I’d been looking forward to it—something new and exciting. My mother brought me. I was holding on to her hand, and she said, ‘Sister, this is my boy Carmine,’ then she went away and left me.

“The sister must have smiled, but I don’t remember. I wasn’t looking at her face. I was just seeing those strange, long, black clothes and the white headdress. ‘Has she got any hair?’ I asked one of the other kids. And they all laughed at me. I didn’t know any of them.

“Of course, it was their first day, too, and they must have been as scared as I was. Later on, we got along all right. And the sister was a nice, kind woman, a good teacher. But from that day on, I never really liked school. It didn’t frighten me afterwards—just bored me, mostly. In high school, there was an English teacher who was a favorite of mine, though. He opened up a new world for me—gave me odd things to read, like The New Yorker.

“But math—did I hate that! The old woman who taught it had a special thing about me, it seemed in those days. She was sure to ask me questions she knew I couldn’t answer. So do you know what I did?” John turned toward me, suddenly wry. “I cheated! If there was a quiz Corning up, I’d look in the book and write the answers between my fingers.

“Would I do it today? I’d find better ways to cheat,” John laughed. “No. Seriously, I’d use that same time for studying, so I wouldn’t have to cheat. We do some pretty foolish things when we’re very young, don’t we?” A Street light flickered across his face, misted with thought and memory. “Like the time I had a crush on a girl for a whole year.”

John Saxon chuckled at the young Carmine Orrico. “I never said one word to her. I just looked and looked. She had red hair and a cute, turned-up nose, I remember. Once, when we were going through the hail, she caught me looking at her. She smiled, but what did I do? Nothing, except tum the color of a fire engine.

“I wasn’t shy with girls—no more than average, I mean. In fact, just before I finished high school, there was one girl I dated pretty steadily. I remember one Saturday night . . . we were supposed to go to a dance When I got to her house to pick her up, her mother told me she’d already gone out—with another boy. I couldn’t even pretend I’d just stopped by, because there I was, standing like a dope with a cellophane corsage box in my hand. ‘Carmen,’ I said to myself, ‘you have been jilted, boy.’ She broke my heart, I guess you’d say ”

His eyes contradicted his light tone. “I can laugh about it now, but it wasn’t very funny at the time. Anyhow, it didn’t make me bitter toward women. They’re just so hard to understand sometimes. . . . Another time, after I got out of school, there was a girl in my neighborhood who acted as if she was fond of me. I’d started to get modeling jobs by then, and she seemed to be really interested in my work. She went out of her way to tell me that she’d seen my picture in True Story. Well, we’d gone out together a few times, and one evening I was walking her home after the movies. It was a quiet Street like this—we’re getting close to my old neighborhood now. I slipped my arm around her and gave her a kiss—very gentle, not much more than just friendly. And she slapped me!”

He put his hand to his face as if he could still feel the hurt and surprise and bewilderment. “But I still wasn’t bitter.”

He had said that twice, I realized, and I wondered whether he was thinking only of two girls that he had known in Brooklyn days. A few moments later, I said softly, “Penny for your thoughts.”

“. . . What? Oh—I was just thinking about tomorrow. Tomorrow in general, I mean. It’s funny how many people you meet today, the places you go. Yet, when tomorrow comes, some of the people are gone and some of the places you’ll never see again. And you’re caught in the middle of it all.”

Some of the people are gone . . . “Like Vicki Thal?” I wondered silently; I didn’t want to ask just then.

He finally spoke, half to himself, as if genuinely trying to straighten out his thoughts by putting them into words. “Why do girls have to pretend so much? . . .

“When a girl is trying to push some quality forward for observation» I can usually tell. During my high school days, I saw so many of them take some sort of external thing from Marilyn Monroe or Elizabeth Taylor and try very hard to look and behave like them. Why do people always want to be somebody else? Why do people copy others?”

Suddenly, he laughed. “I’m a fine one to talk about pretending! See that church?” He pointed to a spire a block away, outlined against the New York sky that is never truly dark. “That’s where I did my first acting—only I didn’t know it. I was about eight or nine, and I was crazy about a comic-strip hero called The Phantom. Sitting at mass with my folks, I imagined The Phantom and me flying into the church together, swooping around and astonishing everybody. ‘Hey, look!’ they’d say. ‘Look at Carmine Orrico!’ And then the two of us would settle down into the family pew, and I’d just sit there, very offhanded, as if I did this kind of thing all the time. That was imaginative acting! . . . Stop!”

The driver pulled over to the curb. “Here?”

“Just for a minute.” We had paused beside a small ice-cream parlor, a perfectly ordinary neighborhood candy store. “This was my first hang-out,” John said. “I always liked to watch people. I’d peer into their faces here and try to understand them. I remember, I told my mother that if you look long enough into any woman’s face you’ll see beauty there. She had no idea what I meant, and it wasn’t really clear to me, either, when I was a boy. All right, driver. Let’s go on now.”

The car moved away from the candy store, but John turned his head, looking back toward his younger self and the lovely illusion in every woman’s face. “What I saw wasn’t beauty, I know now. It was a Symbol of beauty. Today, I see other symbols when I look into people’s faces: what they are; what they’ve struggled to be and aren’t. Through them, I try to understand myself, too. I want to shed my skin and see what’s underneath!”

Unwittingly, he was revealing a great deal about himself. Eager to learn more, I mentally noted the location of the candy store—Thirty-Eighth Street and Twelfth Avenue—and went back later to ask people who’d known John Saxon when he was Carmine or Carmen Orrico. “Funny thing about Carmen,” one young man told me. “If the bunch was crazy about some idea—he’d probably be cold on it. But he could have been the leader of our gang, if he’d been interested. That was because he could figure us out better than we could ourselves. In the corner poolroom, he used to win more money than any of the other guys. He wasn’t a particularly good player—he just knew who the good players were, better than they did themselves—so he’d bet on them.”

“Girls?” another boy said “With looks like his—sure, Carmen went out with the girls. Only, you’d never hear about it from him. The rest of the guys would stand around on the corner and—you know—compare notes on our dates. But he never told tales. I guess he figured his dates were something between the girl and himself.”

That explained a lot, I thought. John had talked to me frankly about girls he’d dated in Brooklyn—but they were unknown to me, and he had not mentioned their names or hinted at their identities in any way. When it came to Vicki Thal, however, here was a known person whose privacy must be guarded—and John Saxon still would not tell tales.

So I spoke very gently when I asked him, “Were you and Vicki married?”

In spite of my delicacy, a dark shadow contorted his features. “I’m not married! I haven’t been married. And I don’t know when I will get married! I’m not seeing Vicki any more. There’s nothing to it.”

He was silent for a moment. The car had stopped for a red light. The light went green, and I heard his muffled voice: “Nothing to it.” He faced toward me. “I’m just annoyed that everyone made such a mountain out of a molehill. Can’t anything ever be kept private?”

Again, he was silent for a time, until he pointed down the Street we were passing. “That’s where I was born— at home, not in a hospital.” A few blocks farther on, he said, “Would you slow down, please?” He was peering out of the cab at a house halfway along the block. “I want to see if my aunt’s looking out the window.”

“At this time of night?”

“What difference does time make? If she’s there, she’s there.”

But not a light shone on the sleeping block. “Turn left at this corner, and left again at the next one. . . . Here’s my house. Be out in a minute.”

It was one of a row of two-family brick houses, with iron fences enclosing the small front yards. John opened the gate. ran up a short flight of steps and went around to the back door, where the lights in the kitchen cast a cheery radiance on the neatly clipped grass. As he had promised, he was back a moment later, with a yellow Western Union envelope in his hand. “They said I’d gotten a wire.

“Nothing important.” He was reading the wire, and a special sort of smile curved his lips. “Just personal.”

I thought I’d better not ask any more questions. As he folded the wire and tucked it into his pocket, I made a harmless comment instead. “That’s a good looking suit, Johnny.”

He chuckled reminiscently. “When I first arrived in Hollywood, I only had two suits, and one of them was a terrible fit. Well, now I have four—and they all fit. I have a red MG, 1953 model and pretty scratched up, but still it’s an MG. I have a nice apartment, even if I do have trouble keeping it straight. Let’s face it—it’s pretty much of a shambles most of the time.

“I tell you what I’d like to find now I’ve been looking for a small house, real bachelor’s quarters, the kind I could close up and leave at a moment’s notice, in case I wanted to go back to Italy, for instance. That’s one of the most beautiful places in the world. I’d like my house to be very simply furnished—just enough for one person.”

Goodbye Vicki Thal, I thought. He sounded defiant, reckless, eager. Okay—let’s see what happens next! That sort of attitude.

John breathed out sharply and slapped his hands briskly on his knees. “I was named for my grandfather. He was a remarkable old man, but I never really understood or appreciated him until the time when I was new in Hollywood. It’s often that way. You have to get a long distance from a person or an experience before the whole meaning. the truth comes through to you. . . .

“Grandpa must have loved me very much. I know that now. But when I was a kid I didn’t really like him. Maybe he scared me a little. He was a hot-tempered old man, an individualist, with a lot of strong opinions. He made his living doing odd jobs around . . . Let’s see, where are we?” John glanced at a corner Street sign. “No, his neighborhood was back there, near where my people live. Grandpa died a few years ago, before I’d gotten anywhere. But I don’t think he’d have been at all impressed with a grandson who was a movie actor. He went to the movies just once, stayed in the theater five minutes and then stomped out. When we asked him what he thought of the show, he growled, ‘All nonsense!’ And he wouldn’t look at television. ‘Silly black box,’ he called it.

“At the time, that made me mad. I thought he was just being stubborn. But everything he said stayed with me somehow. We were talking about religion once, and I said, ‘I can’t help it. I just don’t believe—’

“ ‘Wait!’ my grandfather said. He put his hand on my arm. I can still see his eyes—dark and deep-set. ‘Don’t reject anything that fast,’ he told me. ‘Think. Learn. Maybe some time you’ll find out you can accept it.’ ”

John sighed. “I’m still thinking. And learning, I hope. I don’t believe, but I don’t disbelieve, either. I should have known from that talk that Grandpa wasn’t just a bullheaded old man. His ‘stubbornness’ was really integrity. Any opinions he had, no matter how unusual or unpopular they might have been, were his own, and he’d stand by them. all this came to me the first months in Hollywood.

“There were times when I felt overwhelmed and unimportant. Then I’d picture Grandpa, and that would stiffen my backbone. I’d think, ‘I can be an individual, too. I can stand up for my own opinions.’ That’s how I wound up talking back at the president of U-I!”

Shaking his head ironically, John asked, “Can you imagine a green kid doing a thing like that? Well, I’m not sorry. All I’d done in pictures was ‘Running Wild’—not much more than a bit—when they told me I was pretty well set for the part in ‘The Unguarded Moment,’ the psychopathic high school boy. I’d have to do a test first, they said. That made me happy, because the part sounded good, and I began studying and planning. Then I heard that the studio was testing six big name actors for the same part. And I hadn’t heard a word about my test.

“I blew my top! I barged over to the president’s office and demanded to see him. Of course, I was in no position to dictate terms to anybody. The secretary made me wait for an hour and an half. Believe me, by the time she said the president would see me I was boiling mad! I marched in and said, ‘I was given to understand that I’d at least be tested for “Unguarded Moment.” If you won’t do I that much, then there’s no future for me here. I may as well go back to New York.’

“The minute the words were out, the sound of them frightened me. But the president didn’t blow his stack. He just sat there looking at me quizzically. ‘All right, Johnny,’ he said. ‘Cool off. You’ll get your test.’ And I got it. Even if Grandpa thought the movie business was nonsense, I don’t think he’d have been ashamed of me that day.”

“He’d have been proud,” I said.

“Well, I don’t know. . . . Sometimes I don’t feel so sure of myself, even now.”

Around us, the houses had thinned out; across the open lots between them a wind blew gently off the bay. As the car turned in toward the big structure of the Town I and Country Club, from which the Barry Cray show is broadcast, John said, “Here we are. Oh, I’ll be all right when I’m on ‘ the air. That’s part of my work. But sometimes when I wake up in the morning, I have the most awful, helpless feeling. Soon as I step under the shower, it goes away. The water’s bouncing off me, and I think, ‘Okay—bring on another day! Make it something different—a tough job, a new challenge. I’m set for it!’ But for those first few moments after I open my eyes—” He hunched up his shoulders. “I wish I was off on a desert island.”

“By yourself?” I asked slily.

And then I regretted my attempt at humor, for John said slowly, “No. With my ex-girlfriend.”

However jauntily he carried it, John’s torch was showing.

THE END

JOHN STARS IN U-l’S “SUMMER LOVE” AND ‘the WONDERFUL YEARS.”

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE OCTOBER 1958