Profile In Courage

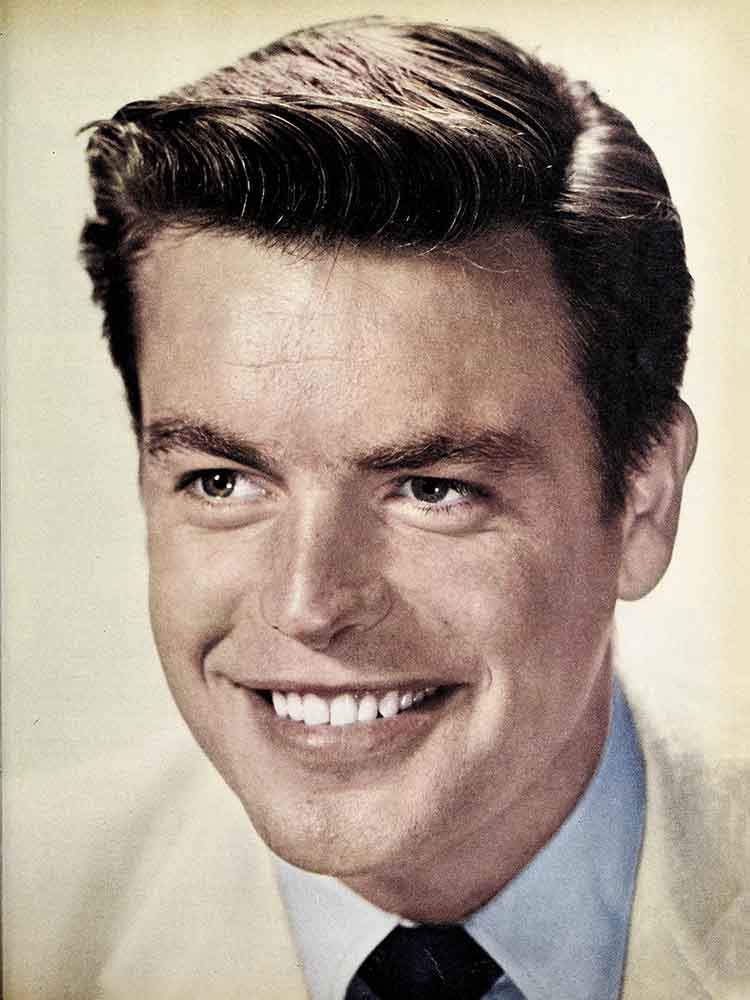

Robert John Wagner, Jr., a 26-year-old film player of “feature” stature in the minds of the industry, but a star in the eyes of the public, reached his studio dressing room one day in the semi-darkness of early evening. He was edgy, voluble and apparently suffering from mild exhaustion. The apparel he was wearing was part sports and part Western, including boots. He was-not altogether happy.

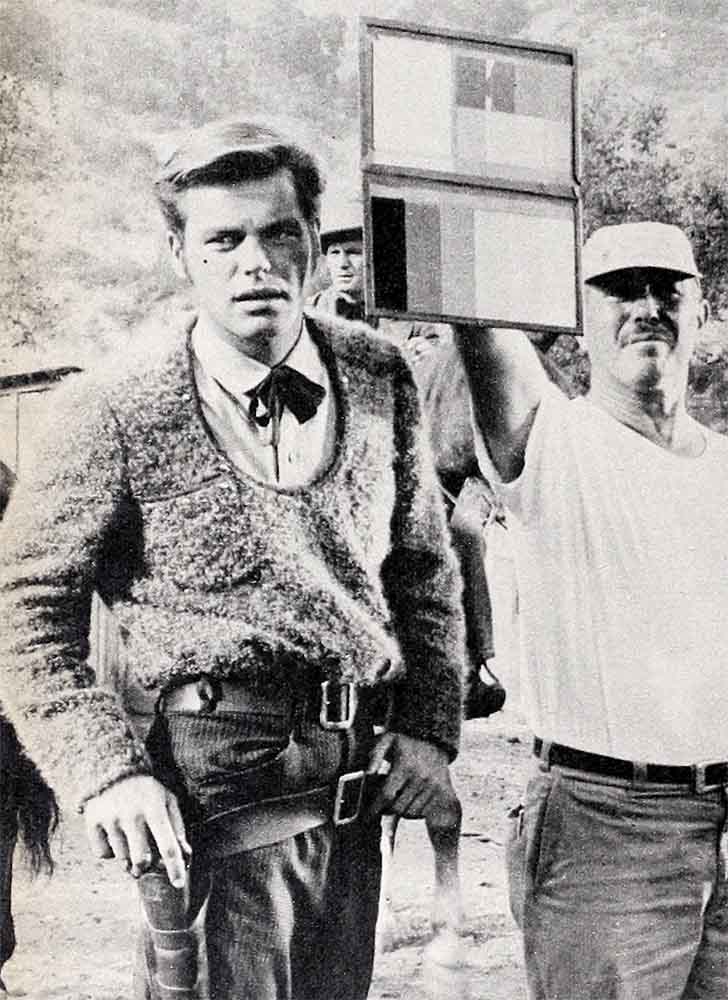

Bob Wagner had spent most of the day “looping,” a term that in Hollywood has nothing to do with exuberant celebration, but means dubbing lines to his own lips in scenes where exterior noises have made them unintelligible during outdoor shooting. It is a difficult and exacting business, and in this instance especially so, since Wagner had had to re-enact the gasping, broken words of a badly wounded man—himself, as Jesse James. Now, however, it was over and, from a bar on one side of the room, he poured himself a fair-sized Scotch and water. “You can call it a Coke if you want,” he said to a visitor. “But you don’t have to. How I’m sick of that Coke bit. ‘For recreation, Bob likes nothing better than an early movie and a Coke,’ ” he said with a rather bitter overtone. “I think maybe we’ve outgrown that.”

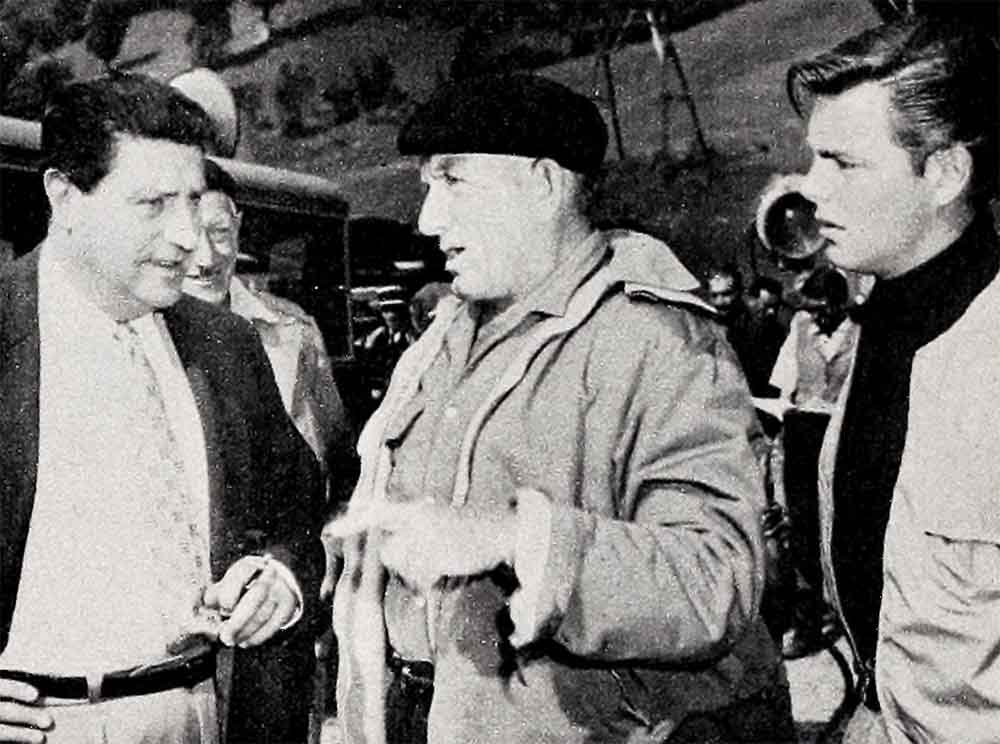

AUDIO BOOK

“Dressing room” as a description of the studio quarters of an actor of Wagner’s professional rank is both a misnomer and an understatement. Situated on a second-floor level directly across from the 20th Century-Fox commissary, the setup is more properly a suite or even an apartment: a kind of office in the front, behind it a living room, complete with hi-fi and the bar and a lavatory. Wagner’s retreat is also something of a social center, and now, in the cold twilight, several people were present a writer-director named Richard Sale; a man with cropped, sparse white hair and a musical voice whom everyone called Duke; Barbara Rush, a young actress; Nena Wills, Wagner’s secretary, and the casual visitor. Wagner sank heavily into a swivel chair and regarded Miss Rush with something between friendly admiration and mock ecstasy.

“You doll!” he said. “You gorgeous doll!”

Miss Rush grinned at him. “I know,” she said.

“You absolute doll!” said Wagner. “Wait a minute.” He swiveled around to the phone and dialed a number. “Mr. Wagner, Sr.?” he said. “Wagner, Jr., here. I’m going to be tied up just a little. Keep everything hot, will you? Thanks, Dad.” When he swung back, his face had become moody, and for a moment his vague gesture seemed to groom the protruding forelock of hair that characterizes his screen appearance. It is like the hair of the small child who lives next to Dagwood Bumstead in the comic strip. Wagner never brushes it back; he appears to encourage it. “A phase,” he said. “It’s time I came out of a phase. Earnest Robert Wagner, God’s gift to the soda fountain, is not long for this earth. You suppose Jesse James ever had a soda?”

“You can’t be a juvenile forever,” someone said.

“I already have been,” said Wagner. “What’s another eternity going to matter? It’s a funny thing. Somebody says you’re a star. Then somebody else says so. It’s wonderful how everyone agrees to it. There’s only one thing wrong: You’re not a star. You know it. The technicians know it. But it’s too late. The brand is there. You’re in the deep water now. But you haven’t found out whether you can swim. Now I’m learning to swim. So what’s the next phase? I need a phase, I’m not kidding.”

“Movie stars have it the greatest,” the same person said, smiling.

“You’re quoting from my fan mail,” said Wagner. “Just the same, there’s something to it. Any one of us who beefs should be shot. I see people waiting for buses, this time of night, which is real creepy. And I’m doing the only thing I love to do. Plus the salary. No problems.” He looked at his glass as though he expected it to answer him. “No problems,” he repeated.

A man burst through the door. He wore an expensive blue suit; indeed, he looked expensive from top to bottom. He sat down on a sofa next to Wagner with an air of almost violent assertion, and launched without preamble into what was unmistakably an agent’s directive. It was his opinion that Wagner should appear, in a non-speaking capacity, on a certain television show. It was Wagner’s foreboding that by so doing he would antagonize a powerful columnist who also had a television show. Wagner sat, irresolute and worried. Presently he rose and mixed another drink. “About the other thing . . .”

“The other thing” evolved into a request from a famed comedian that Wagner join his improvised troupe on a visit to a far north military base.

The man in the blue suit was of no two minds about this either. “Five thousand dollars!” he said. “You know, he’ll get a television show out of it. Why should you work for nothing? But you ought to go. I’m not talking about patriotism.”

“They don’t want to see me,” said Wagner tiredly. “Why should men in uniform want to see a young jerk like me? What can I do? They want to be entertained. They want to see dames.”

“Don’t let it get you,” said the expensive man. “But don’t forget the money. I happen to know Jayne could have had $10,000 for going. But she couldn’t make it.”

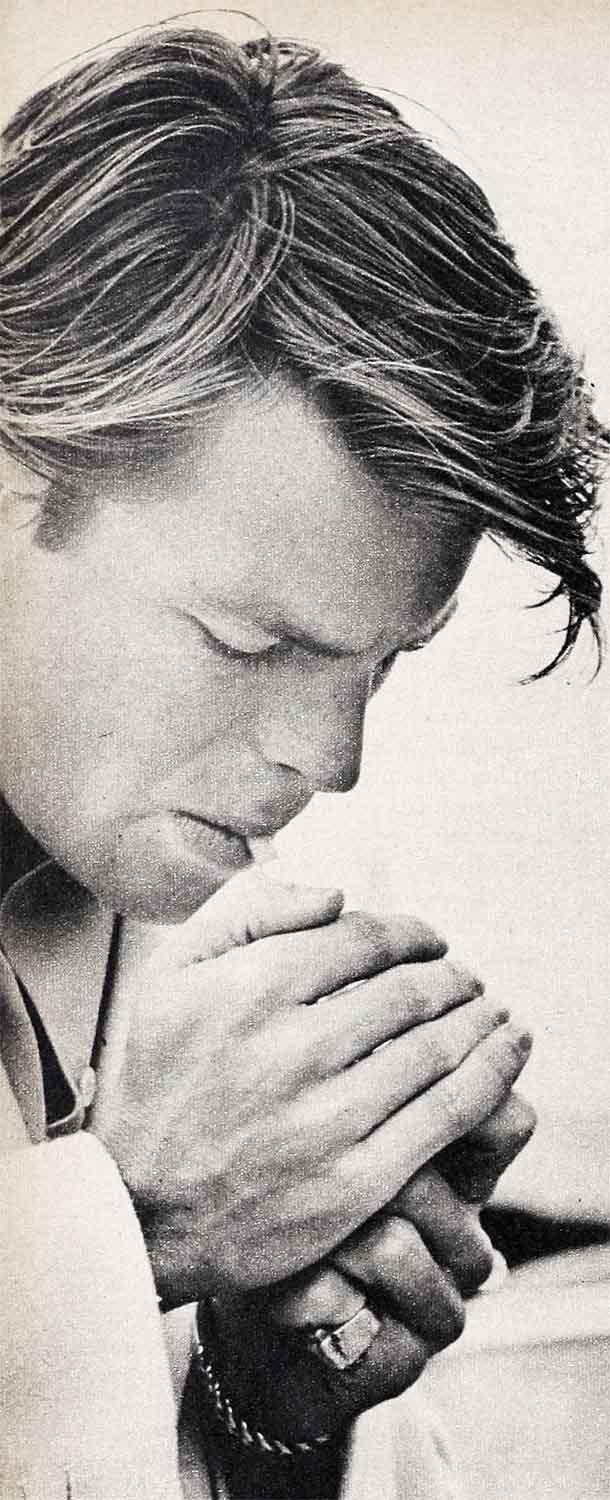

For some minutes more he delivered himself of hoarse, categorical judgments while Wagner sat with his head resting on one hand. When the man left, nothing had been settled. Wagner picked up the phone again. “Wagner, Jr., once more,” he said into it. “You’d better go ahead without me. Sorry.”

The hour was moving past seven; the darkness outside had become absolute. Miss Rush, having proceeded from astrology through certain schools of acting to how young Bob Cummings looked, had taken her departure. But the others waited in the outer office. Wagner’s day, which had begun in the darkness of pre-dawn, was not going to end even in the darkness of post-dusk. He rose and looked out a window, down to the studio’s main street. A movie lot is achingly lonely and desolate after the day’s work. Wagner shivered a little and turned back to the lights of his living room.

“No, we don’t have problems,” he said sardonically. “That’s not true. Being phony-famous and drawing a salary doesn’t make you immune to the problems, and I have a few of my own. I don’t know just what’s going to happen. But if I can just have six years—just six years more—I’ll have it made. Then I’ll have leveled off into a solid character and actor, or at least I’ll have it in the bank. But I don’t know. A lot of very big shots have had this dressing room before me and a lot more’ll have it when nobody remembers or gives a hoot who Bob Wagner was. This is just a tenancy, and sometimes they won’t let you forget it.”

He spoke with a sudden rush. “There was that ‘Lord Vanity’ business.” It was a period picture, scheduled for Wagner, that never got around to being made. Wagner alleges financial difficulties. “After that, I was hung up for eleven months. Word even got around Ne w York that I was begging newspapers and magazines to do stories on me. It wasn’t true. But I guess it made a conversation piece. Then I had this really great picture, ‘Broken Lance.’ Great for me, anyway. And what happened afterward? Next picture they wanted me to do was one of those nine-day B’s. Why? ‘A Kiss Before Dying’—Boy, am I a dirty dog of a warped killer in that one!—should have been something. I still like it. But it’s falling on its face. How do you ever know? That’s what I can’t figure.”

The greatest brains in the business can’t figure such things, somebody remarked.

“But the way I look at it, Spence Tracy’s come along and saved me,” Wagner said. “ ‘The Mountain.’ He asked for me, you know. Gave me star billing with him, right across the top of the picture. And it’s good. A lot of the older players have gone out of their way to give me a lift. Clifton Webb. Barbara Stanwyck. You feel it’d take you a thousand years to get into their class. Or if you work real hard, 995. Gable was another one. He got me going. I used to caddy for him.”

This was not surprising. When Robert Wagner decided, at the improbable age of five, that to be a movie star was an ambition to his liking, he set about it with the singleminded purposefulness of a salmon working its way upstream to spawn. Assuming quite correctly, when the Wagner family had arrived in Los Angeles, that to know the right people wouldn’t hurt, he arranged for himself a paper route in star-studded Beverly Hills. He asked for advice from his clients, and carried golf clubs many miles for film folk of discernment and influence. To mitigate this pushiness, however, it is also obviously true that he has been hardworking and ambitious. As a result, as regards his dramatic talents, he has turned out to be an actor of real distinction.

“Outside of the star part,” Wagner said now, “most of that’s true. You must have been reading newspapers and magazines. But so much of what has been said just isn’t so. Maybe I should go along with it, but it’s just not true. Dad’s no pauper, but I wasn’t born with any golden spoon in my mouth either. Then all those pieces on what I think about women; they must make people just a little nauseous. What do I know about women, for Pete’s sake, and if I do have opinions, who cares? I like women very much. Some of my best friends are women. But my ideas on them aren’t going to shove the Suez Canal back to page two.”

He shrugged sadly at his visitor. “Then like I said, this juvenile bit. I don’t think I’m exactly a creep, but I’m not the distillation of the All-American boy either. I have a fault or two, maybe seventeen. You’ve heard me talk, you know it’s so much malarkey. So go ahead and say I said so. There’ll be no more guff about early dates and ice cream sodas either, I can tell you that. It isn’t me. But on the other end of the range, neither is all this nightclub scuttlebutt. It’s just a fact that I don’t especially go for them.”

Slowly Wagner was divesting himself of a painstakingly developed public personality, and he was doing so without any great reticence. Terry Moore, a friend, a year or so ago read an infatuated account of Bob’s forthright and guileless naivete; she burst into helpless laughter. Like most people, Terry likes Bob; but Wagner is infinitely more understandable as himself than he is in the role of a distortion or a journalistic convenience. His manner is knowing and incisive and precocious, his wit somewhat hard and edged, his social and professional maturity much more glib and advanced than is normal to his age. And his approach to his career these days is a long way from the boy-next-door attitude.

“What I need now,” he said tiredly, as the last visible studio lights began to go out, “is parts opposite these sex jobs. I want to act with them. Jane Russell. Jayne Mansfield. Sure, Jayne Mansfield. I’ve been dating her. That gives the columns a little something for them to chew on. Besides, Jayne is very much on the right side. Then there’ll be somebody else. I’ll keep going. Just get me that six years, that’s all.”

There were lifted eyebrows here and there among the visitors in the dressing room. Wagner nodded. “Sure. Somebody said the other day I was a careerist. So is there anybody in this business who isn’t? I don’t want to sound too cynical, but if you don’t watch every angle, you’re a gone pigeon. Besides, anything’s better than the phony business. The ice cream sodas and the gee-whiz juvenile. There’ll be no more of it. I won’t say there’s a ‘new’ Bob Wagner, but we can absolutely kiss the old one goodbye, whoever he was. Nobody I knew very well, I’m sure.”

It didn’t sound cynical, especially, the visitor remarked. But it might take guts to do.

“For better or worse,” Bob Wagner said, “I’ll go it on my own from here on in. It’s been seven years now, all told. I need that phase; I wasn’t fooling. Whether they like it or not, I’m not a boy. I’m a man. . . . And one more Scotch isn’t going to kill me.”

Now the volume of business out in the office had increased. Late workers were stopping in on Robert Wagner. Some crewmen, who as a group like him very much. An agent with something on his mind. Two publicists with something on theirs. A wardrobe attache. A little man who evidently was bent mainly on a drink.

“It gets like this sometimes,” said Wagner gently. He passed a hand across his forehead and for a brief moment looked intolerably weary. Then his features reassembled themselves and again he wore his curious air of baffled confidence. “Do you mind a lot?” he said. “I’ve got an early call, and I’d like to get dinner before I hit the sack. If I can. If I ever get to the sack.”

He escorted his casual visitor to the top of the several wooden stairs that descended to where a spectacular Cadillac was waiting. In it, Nena Wills, the secretary, would drive the visitor back to the parking lot.

For a second, Wagner stood uncertain, puzzled. “This was anything?” he asked the visitor.

“I think so.”

“You learned something?”

“It seems to me.”

He shook his head, and indicated the half open door of the office. “Wanna swap?”

“I’ll take your salary.”

He laughed without a terrible lot of amusement and walked back inside. Nena Wills drove the visitor to his car. The hour was close to nine; the visitor’s dinner was cold and his wife was irritated. Behind him, the studio lot wrapped its lonely self about Robert Wagner’s bright and noisy dressing room.

A phase was in the making.

THE END

YOU’LL SEE: Robert Wagner in 20th Century-Fox’s “The True Story of Jesse James.”

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE MARCH 1957

AUDIO BOOK