You’re On, Kids!—Betty Hutton & Charles O’Curran

One rainy afternoon last May, while sitting in her dressing room at the Palace Theatre in New York where she was appearing in her own stage show, Betty Hutton suddenly rebelled at the course of her career. She was at the top of her professional life, having earned almost two million dollars before she was 31, but she had come to the shocking realization that all her fame failed to add one whit to her security and that of her husband and children. She had kept thinking it was crazy, a tricky, economic slip-up that would be straightened out. But it wasn’t being straightened out, and she couldn’t wait any longer.

Only a few weeks before this, right after her marriage to Charles O’Curran, this depressing truth had been made clear to her again. Like a new bride will, she had been musing contentedly on their future together. “Just think,” she speculated once, “if I wanted to—which I don’t!—I could give up the screen and stage and just be a wife. After all, you have a good job. We could get along.”

“We could not only get along,” Charlie assured her, “but we would have just about as much left, after taxes, as if you were working.”

Since Betty was then getting $5,000 a week (and had been for seven years), she patted his head consolingly and said she was sure he would feel better in the morning. “It must be something you married that’s disagreeing with you,” she told him. But Charlie found a pencil and proceeded to prove his point. Even though, as a dance director, he made only a fifth as much as Betty, their combined income put them into such a high tax bracket that they would have practically as much for themselves just living on his salary.

Betty was hypnotized by his figures. “What’s it all about then?” she asked. “I’ve worked ever since I was a kid. All those years fighting to get somewhere and . . . and it’s just glory? If I keep on like this, I won’t have an extra cent to chip in for us or to use to safeguard my children? Nothing but a big whoop-de-do I couldn’t exchange for a loaf of bread?”

“Nothing,” Charlie had answered. “So just be a wife and let the old man bring in the money.”

“But . . . but I can’t!” she had exclaimed. “You know I love to work. I’ve got to work. It’s in me and has to come out. Yet it should mean something to us. It ought not to come to nothing.”

Betty kept dwelling on this talk. Then she got the idea of Charlie producing a stage show around her to be booked at the Palace. “Don’t!” everyone warned her. “You cant follow Judy Garland.” But as if she were bound to test herself (and she was), Betty went ahead. Waiting for the opening in May was like holding her breath. Then . . . a smash success. Yet, even this didn’t change the basic situation and now, on this afternoon backstage between shows, Betty could not contain herself any longer.

She phoned her agent, Abe Lastfogel of the William Morris office, and, dressed in an old pair of slacks, went out to meet him in a small delicatessen store near the stage entrance. When he got there, she was at a table staring moodily at a 40 cent sandwich she had ordered but apparently couldn’t eat. She tried to control herself as she talked, but the tears came before two words were out. She announced broken-heartedly that she could no longer go on in Hollywood as a studio star. She must strike out for herself.

They talked for an hour. “All I own to my name today,” she told him, “is the house we live in. After all my years of struggling! . . . and I would have lost that if my show at the Palace had flopped.

He knew what she meant. Despite her high earnings, Betty had not had enough clear money of her own to organize the stage company and had to pledge all she owned to swing the financing. But he also knew that Betty had always been a victim of the performer’s inborn fear of being “at liberty” i.e., unsigned and without a steady income. She had had her days with “short meals,” her weeks of pinching nickels, sometimes borrowed nickels. He reminded her of it.

“If you want to be independent and go into business for yourself, that’s fine,” he said. “For taking the financial risks involved. you are permitted to profit more. That’s business. But these are touchy times. If you win . . . great. But if you don’t . . . you can sink everything.”

“I don’t care,” she cried. “At least I won’t have to be ordered to sing such and such a song or do this or that picture. I’ve been in show business all my life and I am full of ideas and feelings on what I want to do. When I want to do them now, I am told to forget about them.”

“It’s up to you,” he replied. “But make sure.”

Betty went to Charlie. What she wanted to do was form separate companies for the presentation of their own pictures, stage shows and television productions. “We’re a perfect husband and wife team,” she pointed out. “You could produce and direct the show. Would you be willing to gamble?”

It was a gamble for Charlie because he had six years of his contract left. Besides, since he was not an actor and did not have to work in front of the camera, advancing age would not lessen his value to the studio to any appreciable extent. He could look forward to a good salary as a director as long as his knowledge of showmanship stayed with him. But his answer was, “It’s all right with me.”

When Betty made her Honolulu trip to rest up from her New York showing, and her USO trek to Korea which preceded it, she worried about her decision to leave the studio and go on her own. Then she got a wire from Charlie: “Dear Maw, you’re on,” and knew that it was too late to turn back. The wire meant Charlie had booked her to appear with her own company at the Palladium Theatre in London in September. It would be the start of the new venture. There remained before them only the task of settling their contracts with the studio and they were off.

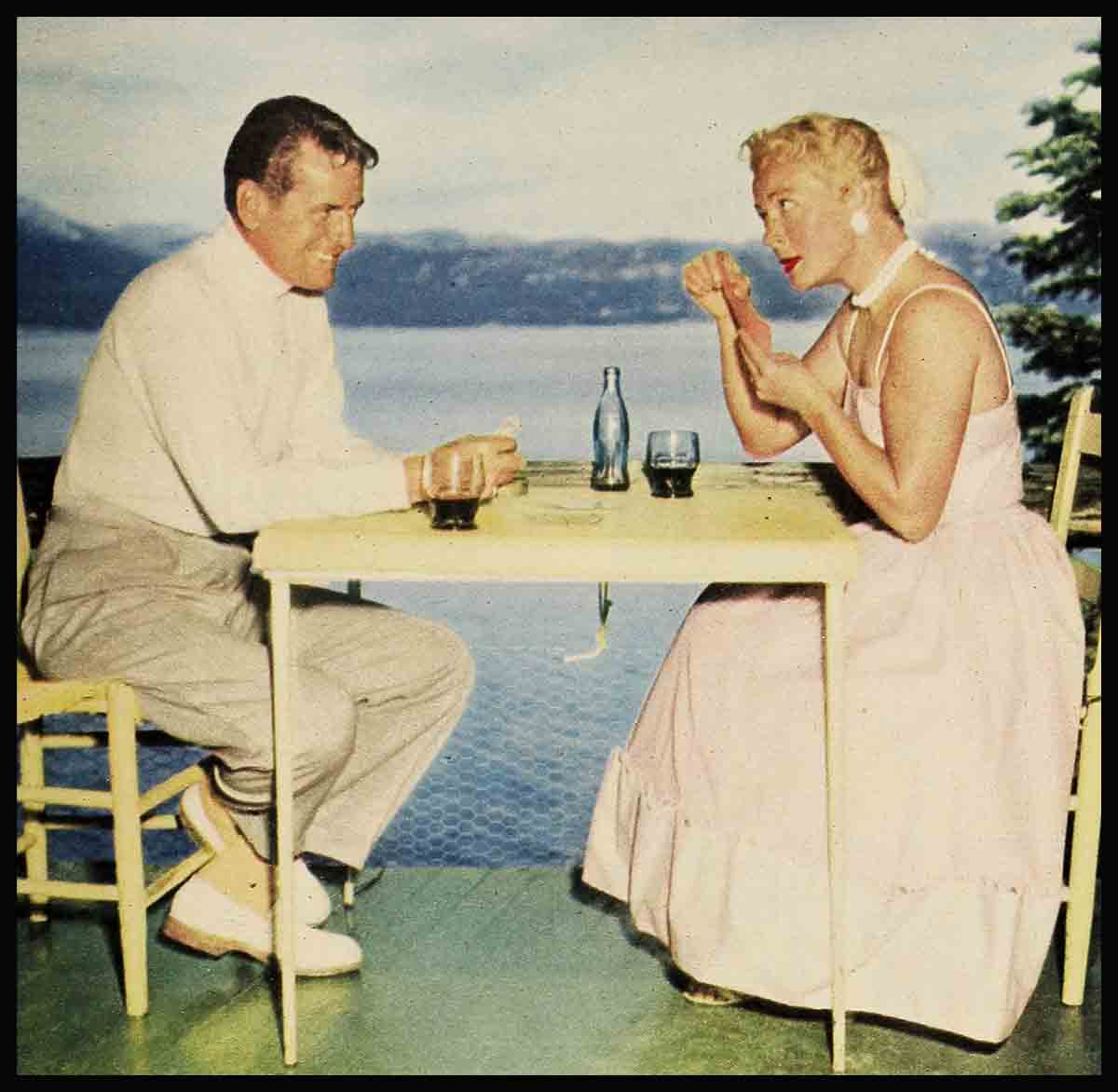

On her return from Korea, and with Charlie free of picture obligations, they decided to take their long-delayed honeymoon at Lake Tahoe.

The first two weeks there, they were alone in a small mountain cottage. Betty insisted on doing her own cooking and cleaning. It was a wonderful honeymoon, but also one which found them doing some serious thinking at times, because they had chosen to take it when their whole future was up in the air.

Some days they felt they were getting too concerned for their own good so they’d decide to forget about it, relax and have fun. They got to know their vacationing neighbors, Tom and Betty Dwyer, a San Francisco couple, and accepted their dare to take up water-skiing. When they got down to the lake’s edge, Charlie felt the icy water and announced that he wouldn’t even put his foot into it, let alone try to water-ski over it. Yet after only a few attempts they were both flying across the water like professionals. “You know, I’m awfully glad we learned, instead of quitting,” Betty said to Charlie once. “It gives me confidence for what’s ahead of us.”

Nights when Betty felt like playing the lady, they would dress up and dine at the Cal-Neva Lodge, ordering everything plus the trimmings. The next night she would be back in the cabin trying to do something to a stew to make it taste as good as the steaks of the evening before. Occasionally, Charlie would assure her she had succeeded.

One night Betty achieved new fame—as a card dealer. They were out with some new friends and chanced to find themselves in a gambling room on the Nevada side of the state line. Betty was invited to deal the blackjack game. For the next ten minutes, not a player lost. She handled the deck so that the hole-card was always visible, plus most of the other cards as well. One player needed an eight to win a big bet. Betty fanned the deck to find him one while the gambling manager tore his hair and made frantic signs at her over the heads of the players that such solicitude was not required of a dealer.

They had their fun. They also had their scares. Betty’s cook brought her two little daughters, Lindsay and Candy, along with her and one afternoon when Charlie was chasing Candy he suddenly tripped and went down.

Betty ran up and the expression on his face was so tense that she thought he had broken his leg. He shook his head and said he thought it was just a sprained ankle. “But,” he added, in a worried tone, “the last time I had a sprained ankle I was on crutches for three months.”

Suddenly she knew what he meant. The rehearsals for the Palladium . . . their first show as independents! These all depended on Charlie . . . on a Charlie who could move about and demonstrate exactly what he wanted.

They called a doctor and, after he had examined the ankle, he diagnosed it as a sprain but not a serious one. Charlie would be as nimble as ever in a week or so. They both heaved a sigh of relief, and they realized they were beginning to learn what it means to be completely on your own.

Then Betty’s throat began to bother her again. It was a recurrence of an old complaint. A year before she had been operated on for removal of what the doctors termed “singer’s nodules” on her vocal cords. There was a chance now that some minute growths had been overlooked. When they got back to town, this was confirmed, and Betty decided to go through another operation.

Betty came out of the ether a little too soon for her own peace of mind. Her doctors were still in the room, unaware that she had regained consciousness, and she heard the anesthetist congratulate the surgeon. “Frankly, I didn’t think you would be able to get those tiny cores of the nodules,” he was saying. “It was such delicate going.” She closed her eyes. “Oh, murder!” she thought, realizing that only a small fraction of time ago all the remaining song and music within her could have been permanently dammed up by the slightest deviation of the scalpel in the surgeon’s hand.

By the time she was out of the hospital her plans had become known and she and Charlie began to get reactions. Some people feared for her. But the two opinions she valued the most came, respectively, from her hairdresser and from Alan Ladd.

“Now you won’t have to live like a Prussian general,” said the hairdresser. “Getting up, eating, working, rushing, all on a schedule for the benefit of others.” And Alan sent word, “There is nothing else a Betty Hutton could have done.”

As this is being read, Betty should be finishing her English tour. When she gets back to Hollywood she is going to star in Some Of These Days, a picture based on the life of Sophie Tucker. Six years ago, when Sophie wrote her autobiography with this same title, she came to Betty and insisted that she was the only one to play her on the screen.

Betty had demurred. “You’re too vital,” she had told Sophie. “What right do I have to impersonate you?”

“You’re crazy!” was the blunt Sophie’s reply. “It’s you or nobody else.”

It will be Betty. And it will be Betty in a lot of other presentations she and Charlie are cooking up. They work together always. They work together so much that often their business talk gets mixed up with their more personal conversations. For instance, one night before they sailed for England, Charlie looked into Betty’s brown eyes and asked, “Are you glad you married me?”

She flung a pair of arms around him with the gusto that is typically Betty Hutton’s. “If you hadn’t married me, I would have had to hire you!” she told him.

THE END

—BY LOUIS POLLOCK

(Betty Hutton can be seen in Paramount’s Somebody Loves Me.)

It is a quote. MODERN SCREEN MAGAZINE NOVEMBER 1952

No Comments