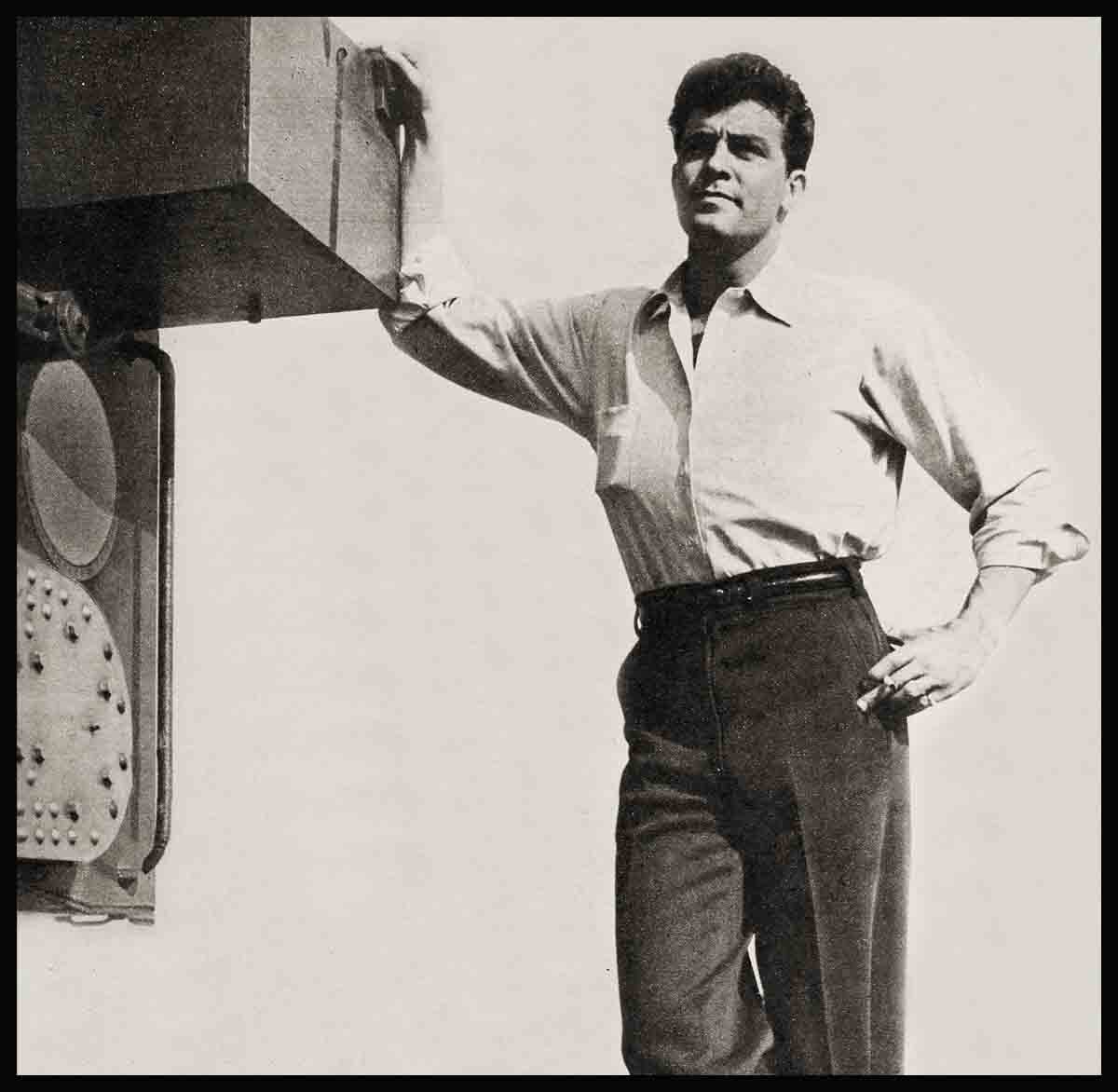

Dale Robertson: “Why I Pray”

My mother had fixed me a bed on the porch swing this hot Oklahoma night and then led me out to it. She helped me in and tried talking me into believing that it was nice and cool out there—as mothers will. As if I cared. I didn’t care and I didn’t answer because I was a ten-year-old boy panicked into dumb suffering. I knew my silence frightened her, made her feel helpless, and I knew it frightened my two older brothers, Roxy and Chet. Their awe and their dread came through in the way they tip-toed around and hushed their voices. But I couldn’t help it. That afternoon, my whole happy, carefree world . . . the bright sun, my mother’s face, had turned a dirty, puffy grey. I was blind.

The old swing creaked as it always did. The crickets chirped. The street buzzed, and the film thickened steadily. I knew I was becoming isolated from those around me. I was only ten but I was growing older fast, old enough to know that there could be no help from those who were trying to help me, old enough to lie out on the porch, feeling my mother’s troubled touch and trying to keep from crying. That would have been childish, and there was no use being a child any longer.

Then I heard someone coming up our wooden porch-steps and a man’s voice asked, “Where is he?” I recognized him as the pastor of the Christian Missionary Alliance Church which we attended sometimes. I heard him walk up to me and then address me quietly.

“Dale, you know me, don’t you?”

“Yes,” I replied.

“Dale, do you believe in God?” he asked.

“Yes.”

“Do you think God can make you see, Dale?” he went on.

“Yes,” I told him.

“Then I’ll pray,” he said. “And I won’t quit until you can see . . .”

Whenever anyone asks me if I believe, or for that matter whenever an evening out here in Hollywood fails to cool off and is a little humid like the summer nights we have out in Oklahoma, my mind goes back to that scene. I remember his praying words, and then how a patch of the grey darkened after awhile and became the silhouette of his head against the lighted living room window . . . and I knew my ordeal was over and I knew I was not going to be cut off from the glory and the color of the outer world. Yes, I believe. Even as that night I knew I was going to see again, I also knew that I would always believe; whatever happened from then on, for the better or the worse, it would never change that.

Many things have happened. But this I have always had to hold on to . . . my belief. This, again and again, and nothing but this. This has given me my philosophy of looking for the good rather than spending any time regretting the bad—in the past or in the future, the bad which has come or the bad which might come. This has made me say about my fate, “If it is right for you, you will get it; and if you don’t get it, it wasn’t right for you.” This I have told others (to a little actress just the other day when she revealed how worried she was about getting a good part) and have seen it give them comfort.

When I started to work in the studios I was so scared, so self-conscious that I simply could not speak or move normally. I would keep wondering what people on the set were thinking of me—the other actors, the grips, the technicians. One day I went back to my dressing room and directed a simple prayer: “Oh, Lord, let me be myself and do my job.”

When I was called back for the next scene, I didn’t wonder whether my prayers would be answered. I knew there would be some results if it was meant that I should continue to be an actor. As I neared the set I noticed how busy everyone was; each man had a job to do and was concerned with it.

“They’re not thinking of me!” I told myself. “How could I have been so self-engrossed as to think that? Why, they would laugh if they knew it.”

That was it. How prayers work out sometimes is not always easy to comprehend, but if your faith is real and your heart deserving . . . they work out. This I know.

Many things have happened but always my belief has held me up. As a boy struck by fever or as a soldier struck by enemy mortar fire, this was the big difference. As a young man trying to make a place for himself or as a young father worried about his wife and child in a first birth, this was the big lift. I would not be without it. I would not want anyone else to be without it. I don’t know how it comes to them. I don’t believe any one religion or church is right and all the others are therefore wrong. I feel the channels to goodness are many and that with belief they all lead to God. I do not have to question whether this is true or not. When you believe, you are past the question. And because I have been past it for a long time I have been happy for a long time.

When General Patton dashed across France and southern Germany and Czechoslovakia after the invasion of Europe, I was a soldier in his famous Third Army. One day he issued an order which frightened the pants off a lot of his men including this Oklahoma boy who was at that moment trying to look the part of a second lieutenant in the 322nd Combat Engineers. The order read: “Hereafter engineers will not stop to remove mine fields during the advance but run through them and suffer the casualties.”

Man . . . it sounded awful! If there was such a thing as soldiers voting for or against their general, our general would have been impeached right then. You could hear the grousing on every side. Why? Did he just want to kill us off quicker? Why not remove the mines? Why run through them and get blown to confetti? Why? Why? Why? How this military directive was going to bother me particularly developed the next day in the form of a suspicious-looking road. An advance group in which I was the ranking officer came up to it and stopped cold. I drove to the head of the line in my jeep, saw that they were all looking at me. I knew instantly what they were thinking. The road was probably mined. What about the new order? Would I follow it and order them on through . . . or would I respect their fears and send a detail out to search and remove mines?

I wasn’t thinking. I was praying. And I was awfully glad that I could pray with confidence. I knew what I had to do. In the army you are not supposed to ask for volunteers for any job that you wouldn’t do yourself. This was that kind of job. While they watched I waved to them to take cover and then I drove ahead and down the road myself. The 23rd Psalm flashed into my head and as I sped along I kept repeating it, or rather two lines from it: “Yea, though I walk through the valley of the shadow of death, I will fear no evil. . . .”

To this day I don’t know what follows after these lines, but these two were enough to do the job. I got to the end of the road where it broke. into a clear area and then turned around and returned to the men. They knew now the road wasn’t mined and started streaming ahead happily without waiting for a word from me. My heart was filled with a wonderful feeling that I had gotten from my prayers, for hadn’t they lifted a load from the hearts of my men as well?

I prayed during the war and I was with men who prayed . . . loud and clear. I had a jeep driver, Donald Granlund, who made no bones about it. One afternoon we were making a reconnaissance along a river and had started back when we ran into trouble. The road ran through a clearing in some woods and the Germans had let our jeep through without firing, in the hope, probably, that other Americans were behind us whom they could also trap. But when we stuck our nose into the clearing on our way back, the devil’s own racket broke loose. Donald threw the jeep into reverse and we just pulled back into the safety of the woods in time.

“What are we going to do?” he asked.

The situation was a simple—and hasty—one. We could wait until dark and make a dash for it, provided the Germans didn’t come after us . . . which they certainly would. Or we could take a chance and try to crash through right then. I explained this to Donald.

“What do you think?” He asked.

“Because they’re sure to come hunting us anyway, I and make it now,” I told him. “But I won’t order it if you would rather not.”

“Let’s go,” he said.

I had him back the jeep up until we would have a sufficient run to insure top speed by the time we got to the clearing. Then we rested a few minutes to get our breaths—our last ones maybe—and during this respite I told Donald how the 23rd Psalm had helped me before.

“It’s good enough for me,” he said.

“Okay . . . let her fly,” I ordered.

He did. He shifted through the gears fast and we-hit the open patch and came out into it like a loose bullet—even ricocheting like one as we bounced and sliced along the ruts in the road. If you’ve ever seen newsreel shots of jeeps being tested hurtling along like horses over the jumps you’ll know how we looked. Only it wasn’t funny. Death was screaming in sharp whines all around us. I saw three tracer bullets flash by between my eyes and the windshield. The jeep had a wire catcher in front to cut wires or ropes the Germans sometimes stretched across highways just throat high. One second I saw the wire catcher . . . the next it had pinged off. But above all the noise of the bullets and the roaring motor and the car’s jouncing I heard something else—a man yelling at the top of his voice. And then I realized it was Donald screaming out the 23rd Psalm and making sure he was heard. He was. Or I was . . . for my prayers were just as fervent.

As long as I live I can never forget the simple, abiding faith with which the people of those war-torn countries faced their tragedies. They succored their wounded, buried their dead and went their way quietly. They didn’t need your shoulder to cry on and pretty soon you found out it was because they had Someone else’s. It had an effect on us. We felt we were all one people. In a bombed-out French village we found a two-and-a-half-year-old French girl whose whole family had been killed. There were 163 men in our outfit, and without a word of discussion we immediately all became 163 uncles of little Anna Marie David.

It would seem we did a lot for her when we adopted Anna Marie and kept her with us for nearly three weeks. But it was the other way around. Actually, this little moppet brought a glow of warmth to our hearts. It was as if every man yearned to counterbalance the killing he had to do by helping to preserve a life. The bright spot of the day was when you saw Anna Marie smiling over some present or playing about headquarters contentedly. It made us remember that we were men of families, born of love and with those who loved us waiting at home—and this was something we wanted to remember.

Everyone has heard that old saying that there are no atheists in the foxholes. I don’t know. In my outfit most of the boys were Italian, devout Catholics. There were a few men who never attended services of any kind and it was assumed by some that they were atheists. I still can’t speak for them. But if devotion is holy, then there were no atheists . . . because there wasn’t a single man among us who wasn’t devoted to Anna Marie and whose heart wasn’t wrenched when we finally had to leave her with a Belgium family.

Before I finish, let me get back, in all fairness to his memory, to that order of General Patton’s about advancing right through mine fields. Within a week after the order was posted it began to be apparent to us in the engineer corps that the general made sense. It was true that when we ran through a mine field without clearing it we lost men. But when we took count we found we lost fewer men this way than we had before! The reason was that as many men were killed by enemy sharpshooters and mobile artillery as they squatted around removing the mines, as by the mines themselves. By rushing ahead and either taking the German positions, or diverting their full attention to defending themselves, the whole area was made secure and the mines could then be attended to in comparative safety.

“Why didn’t the big brass explain all this?” a GI as one day wi all come to realize this.

“The ways of women and generals are inscrutable,” a buddy of his answered.

“Yeah, I know,” grumbled the first GI. “But you can’t make love to a general—and that’s another thing I’ve got against them!”

My main reaction to the way things worked out with General Patton’s order has to do with prayer. As I have said, the men were sore when it first was issued, and, I happen to know, a lot of them prayed that it wouldn’t result in their death. What impressed me was that these prayers had already been answered. The general had known what he was doing in the first place. I feel that he, too, must have prayed that he would be right. And he was.

THE END

—BY DALE ROBERTSON

It is a quote. MODERN SCREEN MAGAZINE NOVEMBER 1952

Maria A Perez

4 Nisan 2024Thank you for sharing this history of Dale Roberson and his team and knowing that he believed in God thru Psalm 23 and as his refuge. The Lord is my Shepherd and I shall not want..