“To Teddy, With Love”—Betty Hutton

Our Buttercup’s nine months old, and we’re going to have another baby in April. And another one after that, only we don’t mind waiting a while for the third. But I promised Ted we’d have the first two close together. For companionship, and so Buttercup won’t be spoiled.

I hope the next is a boy. That’s what I said before, but this time I mean it. No guy could be goofier over his daughter than Ted is, but we have our girl now and show me the man who’s not crazy to have a son.

I remember the day we dropped in at a friend’s, and Larry Adler’s little boy was there. He had one of those gimmicks you drag around that makes music, only it wouldn’t work. The minute he spies Ted, over he trots, because with kids my husband goes the Pied Piper one better, he doesn’t even need the pipes.

“This is supposed to play,” little Peter says. “Will you fix it for me?”

I left them together, and next time I looked, the kid has his arms wrapped around Ted’s long legs, and there they stand, six-foot-two and no-bigger ’n-a-minute, smiling at each other with the lovelight in their eyes.

On the way home Teddy was still in a dream. “Wouldn’t it be wonderful to have a son?”

“Honey, here’s news for you. Sometimes you get two daughters in a row—”

“I’ll buy that, too. But there’s always the chance she might decide to be a boy—”

What about your career, people used to say, when I’d talk about wanting another child right away. Peachy, I’d tell them, but my home and my marriage have come to be twice as important. They’d look at me cross-eyed, and I can’t say I blame them. That line’s pulled so often around here and then, six months later, zip! goes another marriage. But the lovely part is, I don’t have to prove it to anyone. Ted knows it’s true, I know it’s true, and the rest doesn’t matter.

I didn’t always feel this way. It was something I had to learn, but I learned it good, and my husband taught me. In Dream Girl—that’s a plug, which is the least I can do for Paramount—they tell me you see a new Betty Hutton, so new you could sit through a scene or two and not know her. Well, that’s how it is with me, Betty Hutton Briskin. Looking back at the girl I used to be, she’s like somebody else. I was getting tough. There was something inside of me getting bitter and hard. Whatever the thing was, it was making me sick.

“What’s wrong with you, Betty?” Mother used to say. “You act like you can’t stand yourself.” hard to please . . .

No kid could have been more career-crazy than I was, and the career was healthy, so I should’ve been riding high. Instead, I was tied into so many knots they could have used me for a fishnet. For one thing, I was always frightened. If the last picture was good, maybe the next wouldn’t be. If I crossed the lot and ‘somebody didn’t say hello, I’d go home and brood. If people were nice, that didn’t suit me, either. They don’t give a darn about you, I’d say, they’re only nice because you’re doing okay. All I trusted was the career, so I hung on to that with hot little hands and knew if I lost it, I’d lose my mind. But having it didn’t make me happy.

Then I met Ted and we fell in love and married. On the surface we were nothing alike. I was the whirlwind, he was the quiet one. Yet with all his quietness, he’d stick to what he believed and come out on top.

For instance, the first day I worked after we were married, he said: “I’ll drive you to the studio.”

Well, I kicked. Not that I didn’t want his company, but he was busy getting his camera plant started, and the whole thing struck me as silly. Here I’d been on my own more or less from the age of 12, and now all of a sudden I had to be driven to work! For what?

He told me. “Look, Betty, you’re away from me all these hours in a different world. I don’t have to punch a timeclock. That makes us lucky. It gives us more chance to be together and talk. It helps make our marriage stronger.”

To me this was a new angle. One reason I was so mixed up, I never took time to sort out what I thought, just let my feelings run away with me. Teddy’s life chad been simpler, he was like the guy in the play, he knew what he wanted and his bean worked straight.

“If you’ll only remember that movies are a business,” he’d say. “Tough and cold like any business. Don’t expect them to love you for yourself, alone. As long as you’re making money, they’ll all say hello. Why should it hurt you? In their place, you’d do the same. So would I. We none of us have time for people who drop out of our world.”

“But I’d always be in your world, huh? If I flopped tomorrow, if I never made another picture?”

“When you love someone, Betty, that person is your world—”

So I got to know what my husband was really like, and the better I knew him, the better I loved him. Loving’s altogether different from falling in love. It’s got nothing to do with charm or good looks. It’s all mixed up with trust and respect and liking, and the best of it is how close it brings you together.

I began to see that no matter how different we were on top, down deep I wanted the same things he did, the things that lasted. And why I’d been frightened was because I didn’t have them. I’m more of an introvert than anyone will know except Teddy, but I’m not frightened now. With him you can’t be. He’s so at peace, with the world. I don’t think he’s ever hurt anyone or done a mean thing that he knows is mean. I have. But I must be improving. Even my mother says, “You’re a nicer girl, since you married Ted, than you’ve ever been.” And coming from my mother, who’s partial to me, that’s quite a statement.

dear little buttercup . . .

Well, then Buttercup arrives on the scene, and if I hadn’t been sold before, she’d have sold me. Here was this little thing with no axe to grind—wanting nothing from me but my hands and my love. That’s the biggest thrill of all—that. she needs me. You can have the most wonderful nurse in the world, and we have, but still the baby needs me. All the books say so, but you can tell it without the books; there’s some feeling of security children get from the mother that they don’t from anyone else.

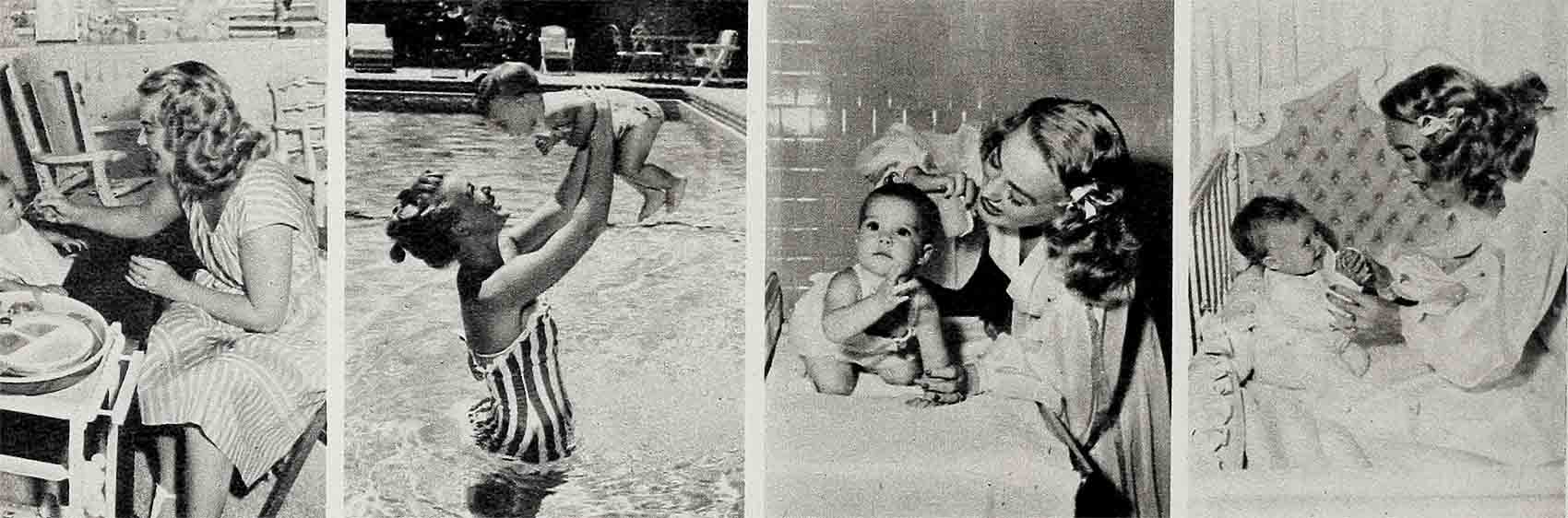

Up until Buttercup was four-and-a-half months old, I took care of her. I fed her and bathed her, the nurse just watched and helped. I wanted her to feel who her mother was. When I started working in Dream Girl, Teddy’d bring her down to the studio twice a week and she’d eat lunch in my dressing-room. If she was sleeping when I got home, I’d go in and kiss her on her little cheek, and I know she knew I was there.

Once she got sick—broke out in spots and couldn’t keep her food down. It was just before the 4th of July weekend. Our doctor was out of town, and it took a while to get hold of somebody else. While he was on his way, Buttercup let out a scream like something hurt her. Talk about knives through your heart! Teddy went white and he got right on the phone and called Chicago. That’s his home town. He started out wanting to be a doctor, so he has lots of doctor friends in Chicago.

“Who’s the best baby doctor out here?” he asked, and I stood waiting with a pencil to take it down. When he said the name, we both did a cave-in. It was the name of the man who was on his way up.

Well, he was wonderful—went. over her from stem to stern, called it something or other that wasn’t serious, and said she’d pull out of it in a couple of days. But you can’t keep calling the doctor every five minutes, especially at night, and that night was gruesome. She’d sleep for a while and you’d start breathing again, then she’d wake up with that awful scream. All that kept us sane was she didn’t run any fever.

Finally, I couldn’t stand it. “Okay,” I thought, “nobody knows what to do, Mommy’s taking over. What would I like if my stomach were upset, I’d like some hot tea—”

We gave her hot tea, and she kept it down. I sponged her and changed her sheets.and did all the things you’d do for a grownup who’s ill. She liked my arms. If I’d leave the room, she’d cry. Only time I left was when I’d feel a bawling fit coming on, then I’d hand her to the nurse and go out and bawl on Ted’s shoulder.

In the morning, I said: “Bet she’d like some milk toast. With a little salt on it.”

“Honey, you sure you’re all right?” That was Ted.

But the milk toast stayed down, and the doctor said, “Mrs. Briskin, you’re not a bad doctor, yourself.” Which is one of the sweetest compliments I ever got.

three’s a family . . .

That night, Teddy and I stood looking down at the baby. She was so skinny you could feel her ribs—golly, what two days’ sickness can do to a kid!—but she was sleeping easy, and the worst was over. Teddy put his arm around me, quiet and strong, and all of a sudden it came over me what they meant about husband and wife being one, because in those two days there wasn’t a thought or a fear we hadn’t shared. Standing there with my husband’s arm around me and our baby getting better, I felt so peaceful and thankful and happy, like coming home out of a storm or something. Here we were, the three of us, a family, loving each other, and whatever happened in a studio couldn’t touch that.

Now don’t get me wrong. I’m not running down my career. Far from it. To me it’s the most wonderful glamorous life there is, plus an education you could never get out of books. In fact, if Buttercup wanted to be an actress, nothing would please me more.

Of course there’d be no urging on my part. She’d have to want it the way I did. Something has to drive you inside, or it’s no good. I put on my first performance at the age of seven. Nobody asked me, nobody even wanted me to. If I’d been a millionaire’s daughter, I’d’ve still been in show business. I left $1000 a week in vaudeville for $50 a week in stock, because I couldn’t stand not to learn every angle of my trade.

What’s more, she’d have to do it the hard way, go barnstorming, learn what a great thing it is to lift yourself by your bootstraps and know when you get there you’ve done it all yourself. Then it means something. Then, her first night on Broadway, ready to go out, she’ll be scared stiff and shaking, with pinwheels and rockets going off in her head, but feeling that marvelous sense of aliveness down to her toes that nothing else on God’s earth can give her. And I’ll be out front like my own mother was, with the goosebumps a mile high—only Mom was alone, and I’ll be clutching hands with a distinguished-looking gent named Briskin, who’ll be trying to look cool and collected while his vest buttons pop—

That’s how it’ll be, maybe. And maybe not. Right now the young lady takes after her father. Likes to figure things out. Slips the strap off her chair and puts it back again. Wants to take light bulbs apart. Chances are we’ll have a lady Edison on our hands instead of a Duse. Better chance that she’ll just get married.

But you see how it is with me. I still get steamed up, thinking back to my own first night. Heck, I get steamed up thinking back to my last preview. But it’s not the same as at first. I’ve had it all. To make it now what it was to me then would be neurotic. There’s a fierceness when you start. Hang on to that, and you lose everything else. Your career means excitement. Your home means warmth and love. Comes a time when excitement isn’t enough—

first things first . . .

To prove it, there’s a deal on for me to do Born Yesterday, and I’m wild for the part, who wouldn’t be? But Buttercup’s brother comes first, and now that we know he’s on his way, Born Yesterday’ll have to wait, or go to somebody else. We’re going to have our babies when we want them, not when the shooting schedule permits. Then, when I start making baddies, which’ll finally happen, I’ll have something else very solid under my feet.

We live so normally now. Nobody tries to impress anybody. The other night Ted brought two fellows home from the plant. They’d been working late, and we fixed them a bite. A friend of mine was there.

“You know what?” I said. “In the old days I’d have taken you quietly aside and explained who these kids were, for fear you might think they didn’t hold their coffee cups fancy enough to associate with a Hutton—”

“And now?”

“Now you can like ’em or not, I don’t give a hoot.”

Whatever was making me bitter is gone. l’ve learned that the world doesn’t owe you happiness. Sometimes it slips through your hands because you don’t recognize it, or take it for granted. Sometimes it comes when you’re looking the other way. All I can say is I’m thankful I found mine and latched on to it, because life would have been empty without it. As a kid, you read fairytales and think every girl’s entitled to live happily ever after. Then you quit being a kid and find out different. But if ever a Prince Charming rode in on a white horse, my husband’s it. He loves me and that baby and his home like you read about in books. It even scares me. What did I ever do to deserve all this?

One of our favorite games is trying to remember what we talked about B.B.—Before Buttercup. Our evenings might seem monotonous to other people, but we think they’re divine. After the baby’s asleep, the nurse comes in and tells us what she did all day, in great detail. All through dinner we discuss what the nurse told us, in great detail. Then we go ride our bikes for a while. Then we come back and, if there’s a moon, you’ll see us pacing and measuring out front.

“The window ought to be here, Teddy, they’d have a better view.”

“Sure, except they’d be looking in, not out. Wait a minute, honey, till I get you turned around—”

That’s for the nursery we’re planning to build, big enough for three kids.

say it over and over again . . .

When we’re in bed, it starts from scratch. “Did I tell you Grandma said she’s the prettiest grandchild?”

Ted’s folks have all been out here except his grandmother, who’s too old to travel. So last August we took the baby to Chicago for a week. If I’ve told him once, I’ve told him fifty-nine times that Grandma said Buttercup was the prettiest grandchild. But he’s just as tickled as he was the first time.

“Bet she tells that to all the mothers—”

“Why not? She’s smart. Wasn’t it wonderful the baby took her first steps there?”

“I had all I could do to keep Dad from phoning the papers.”

“See that? Lucky we’re having another one right away. The child would be ruined.”

And so on into the night.

When the nurse is off Sundays, we take care of Buttercup together. If it’s warm, we whip her into the swimming-pool. Then I dress her up pretty in a pinafore and poke bonnet, and parade her round the neighborhood in her Taylor, Tot, and she waves at the trees because she thinks they’re waving at her. Meantime, Ted’s taking pictures. He looks terrible. All the things I used to couldn’t stand. If a guy wasn’t shaved, I wouldn’t speak to him. Id have no part of anyone who smoked a pipe. Now here he is, the man I love. Old, beaten-up clothes. No shave. Forever with the pipe.

Often, we’ll be sitting home of an evening, and I’ll look at him and some little scene’ll flash through my head—Ted rocking the baby to sleep or just walking around with that silly pipe in his mouth—and it’ll come over me in a rush how good and how wonderful and how sweet he is, and I’ll go running to him and kiss him.

He’ll be pleased, but puzzled. “What the Sam Hill happened to you?”

I’ll grab him and throttle him. “Oh Teddy, I love you so—”

“Do you, honey? That’s good.”

I let it go at that. Why involve him in explanations? He might get mixed up, and I don’t want him mixed up. I like him the way he is. Not perfect. But as darn close to it as you’d want a man to come. I have a special prayer now. Please, God, send us a son. Teddy wants one, and I’d like another guy like the guy I’ve got.

THE END

—BY BETTY HUTTON

It is a quote. MODERN SCREEN MAGAZINE DECEMBER 1947