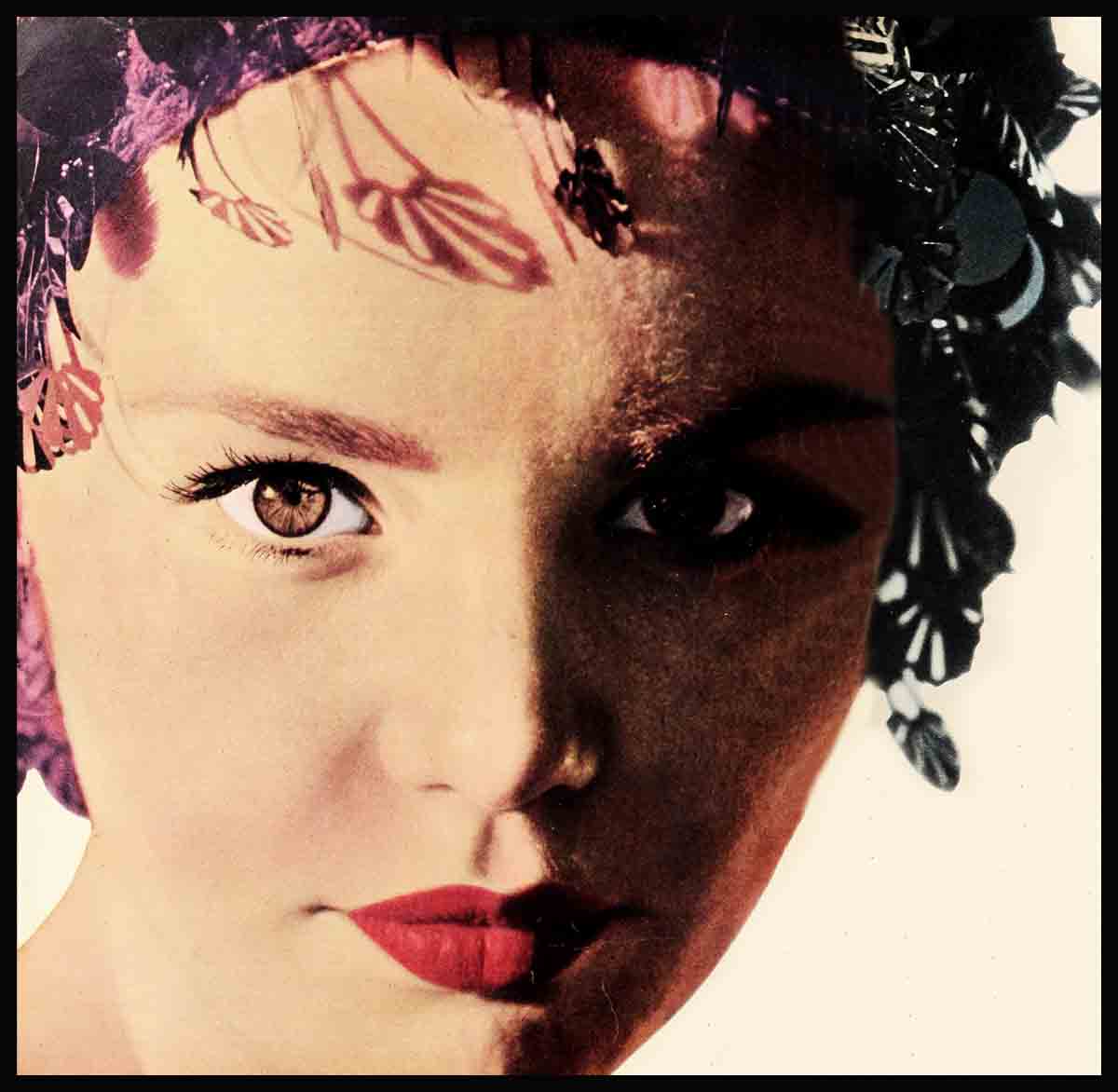

At 16 I Know I’ll Never Have A Husband Or Children—Tuesday Weld

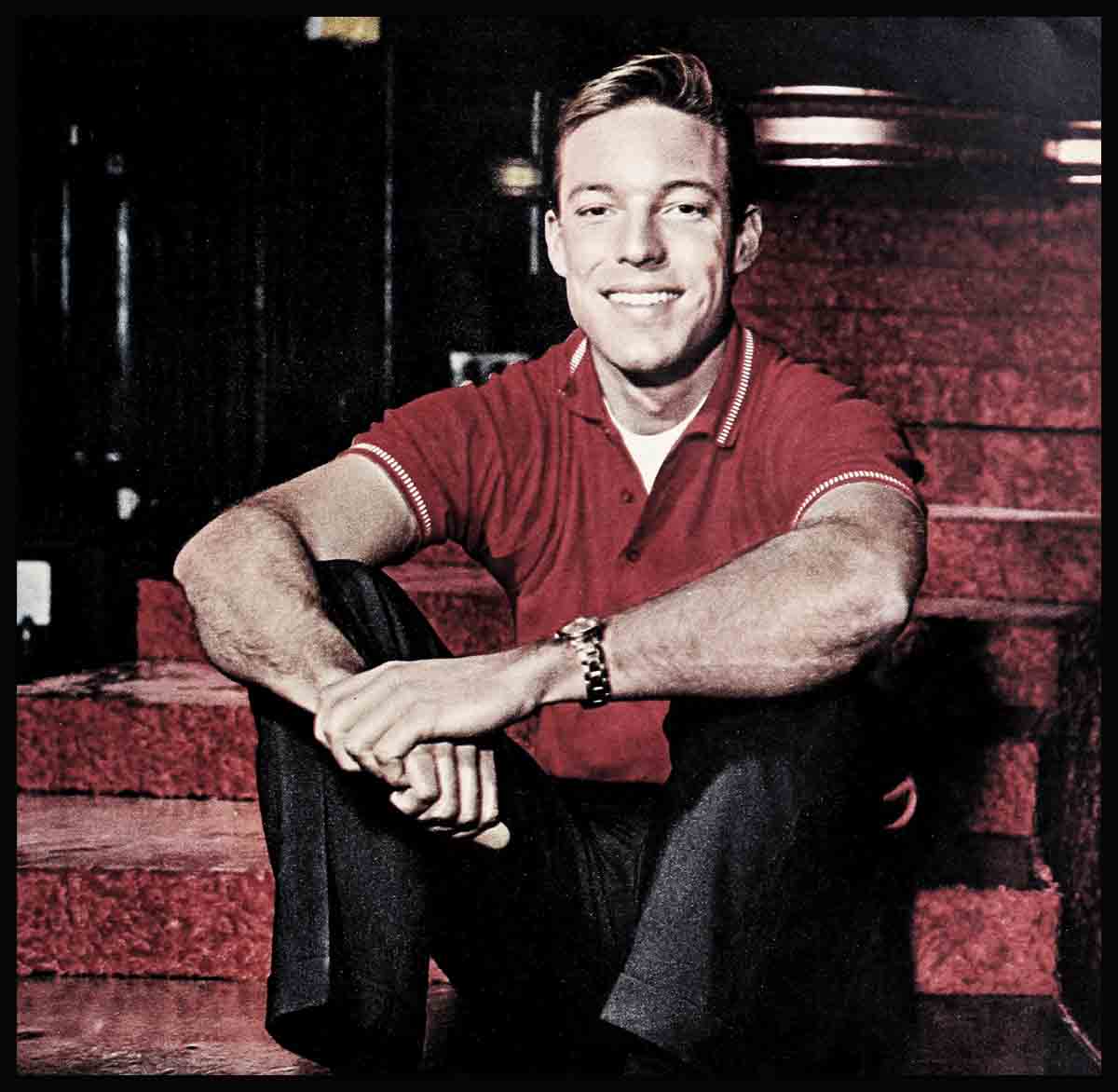

Actually, Tuesday and John met on the set of Spartacus at U-I Studios. Tuesday, wearing one of her famous beatnik outfits that day, levis, sweat shirt, sandals and mix-master wig, was visiting the set with a friend, Marsha. John, in the picture, was doing takes on a scene with Kirk Douglas and Laurence Olivier. The introduction was made between a pair of takes by Marsha, who had known John for several years.

It was a very uneventful-seeming introduction, short and sweet.

John said hello, Tuesday said hi, John turned to talk to : Marsha for a few minutes, and then he went back to work. As he did, Tuesday sighed. “He’s the ultimate,” she said, “the absolute ultimate.”

“Lots of women’ll agree with you on that,” said Marsha.

“Who is he?” Tuesday asked. “I mean, he’s got me all with a pepped-up heart and everything already.”

Marsha gave her a quick run-down on the tall, rugged-looking, strangely-attractive actor. John Ireland, she said, had the reputation of being (one) a hyper-individualist and (two) a ladies’ man. Regarding the former, Marsha said: “He’s a free-thinking, free-talking guy, very salty, very sophisticated, very wild, who does exactly what he pleases, when he pleases.” Regarding the ladies—“He’s been married twice,” Marsha said. “But there’ve been lots of other loves. Just last year it was Kim Novak. They were crazy about each other. But her studio didn’t like it and one day—he was visiting her on the set, you see, and he’d been warned to keep away—and on this particular day two men actually picked him up from under the armpits and threw him out, right onto the sidewalk on Gower Street. John got up and said, ‘No woman is worth this.’ And that was the end of that love affair.”

Tuesday giggled.

“He sounds wonderful,” she said.

Marsha nodded. “He is,” she said. “Also—I forgot to tell you—he’s forty-five years old.”

“Oh yes?” Tuesday said, looking away from her friend and back at the action on the set. . . .

To the bitter end

It was two hours later—about 7:00 p-m.—when he came walking over to where she was standing.

“You still here?” John asked.

“Yes,” Tuesday said. “Marsha had an appointment and had to go. But I—I felt like staying, to the bitter end.”

“We’re going to be shooting till midnight,” John said.

“That’s good,” said Tuesday. “I mean, midnight would be the perfect time for us to meet—really meet—alone.”

“What?” John asked.

“Would you come home with me after you’re finished?” Tuesday asked. “I’d like to be with you. To talk to you . . . You see, you fascinate me. And I hear we’re quite kindred in spirit—just like one another.”

John cleared his throat.

“How old are you, Tuesday?” he asked.

“Fifteen,” she said. “—Sixteen in August.”

“Do you know,” John said, “that I have a son—let’s see—six months older than you.

“Well, how about that!” Tuesday said. Then: “Will you come?”

John looked at her, incredulously, for a moment.

The next moment, he was laughing.

“You’re quite a little character,” he said.

“I guess I am,” Tuesday said, not laughing. “But at least I’m an honest one.”

Then she asked again:

“Will you come? I’d like you to come home with me, for just a little while, tonight.”

John found himself nodding.

“Yes, I’ll come,” he said. . . .

“My own place”

“I can scream, play hi-fi as loud as I want, do anything. It’s the first time I’ve had my own place,” Tuesday said as she showed John around the new Hollywood Hills apartment. “It’s a divine feeling.”

“You live alone?” John asked.

“Practically,” Tuesday said. “That is, my mother has an apartment upstairs. But she lets this be my place. . . . And we get along better this way. We usually get along okay. But we fight sometimes about some of the boys I date, my smoking . . . things.”

She walked over to a small bar to pour John a drink.

John, meanwhile, sat on a long couch and picked up a scrap-book from the coffee table in front of him.

It was titled Me! and was crammed with newspaper and magazine articles on Tuesday, all written since her arrival in Hollywood only a few months earlier.

John was scanning the fourth or fifth article when Tuesday walked over to him, handed him his drink and sat alongside him.

She looked down at the book and pointed to a line that read: Says director Rod Amateau—Tuesday Weld has been around for centuries. That’s why she knows so much. She cut Samson’s hair and kept running.

She smiled. “That’s cute,” she said, “isn’t it?”

“Yeah, sure is,” said John, taking a swallow from his drink. Tuesday reached over and took the book from him and turned the page.

“I think this is cute, too,” she said, pointing to something else. She read aloud: “ ‘I know it looks like I bite my fingernails,’ says Tuesday Weld. ‘But it’s not true. Actually, I have someone come in and bite them for me.’ ”

“Did you actually say that, all by yourself?” John asked.

“Yes, I did,” Tuesday said.

John began to laugh.

Tuesday looked at him, quizzically.

“Are you teasing me?” she asked.

“A little,” “Now let’s get back to this publicity folder of yours. . . . else do you think is cute?”

“Well,” said Tuesday, turning another page, “this, what Sheilah Graham wrote: Tuesday has a Saturday sophistication. I like that.”

She turned still another page.

“But this,” she said, “She’s a combination of Shirley Temple and Jezebel—I don’t care much for that.”

She turned more pages, continuing to read aloud from here and there and smiling as she did:

“ ‘I hate clothes, Tuesday Weld will tell you. ‘I’d never wear underwear if I didn’t have to—and sometimes I don’t.’

“ ‘I’m a kleptomaniac. I like to take things—not big things, little things.’

“ ‘I’ve been dating since I was twelve. Now that I’m fifteen, I guess I know a lot more about men and boys than most girls my age.’

“Quoth the wild Miss Weld: ‘I haven’t read “Lolita” yet. But everyone keeps mentioning her to me.’

“ ‘I’m part little girl— bigger part woman.’

“ ‘Everybody’s trying to make me dignified—and I’m rebelling. My motto is: Obey your impulses!’ ”

A nice sip of scotch

She looked up from the scrap-book and over at John.

“My impulse right now,” she said, “is to have a nice sip of your Scotch.”

John shifted the glass he was holding into his other hand, away from her.

“No, ma’am,” he said.

“Why not?” Tuesday asked.

“Because you’re a child,” John said. “And children don’t drink Scotch.”

“A child?” Tuesday asked, the smile that had been on her face disappearing.

“A child?”

John nodded, and shrugged.

Tuesday reached forward onto the table and lifted a cigarette from a box that sat there, and lit it and took a long drag.

“I am not a child, I am not normal, my life has not been like that of the average girl,” she said then, her voice even, almost hard. “It so happens that I’ve known mature responsibilities since I was a child of three. when I started modeling. . . . That’s right, at three.”

She took another drag on the cigarette.

Her face began to flush.

“I began modeling at three.” Tuesday said, “because we needed the money. Because my father was dead and my mother has three children to bring up and because we never knew from one month to another if we could even pay the rent on that stinking cold water flat we had to live in. So I was pretty and I went to work. At three. And that’s the way it’s been ever since. Working. Working. Getting up for assignments at seven, growing up at ten, eleven—”

She stopped and shook her head.

She looked as if she might begin to cry, suddenly.

“My life has never been like the average girl’s.” she whispered. “And I am not a child.”

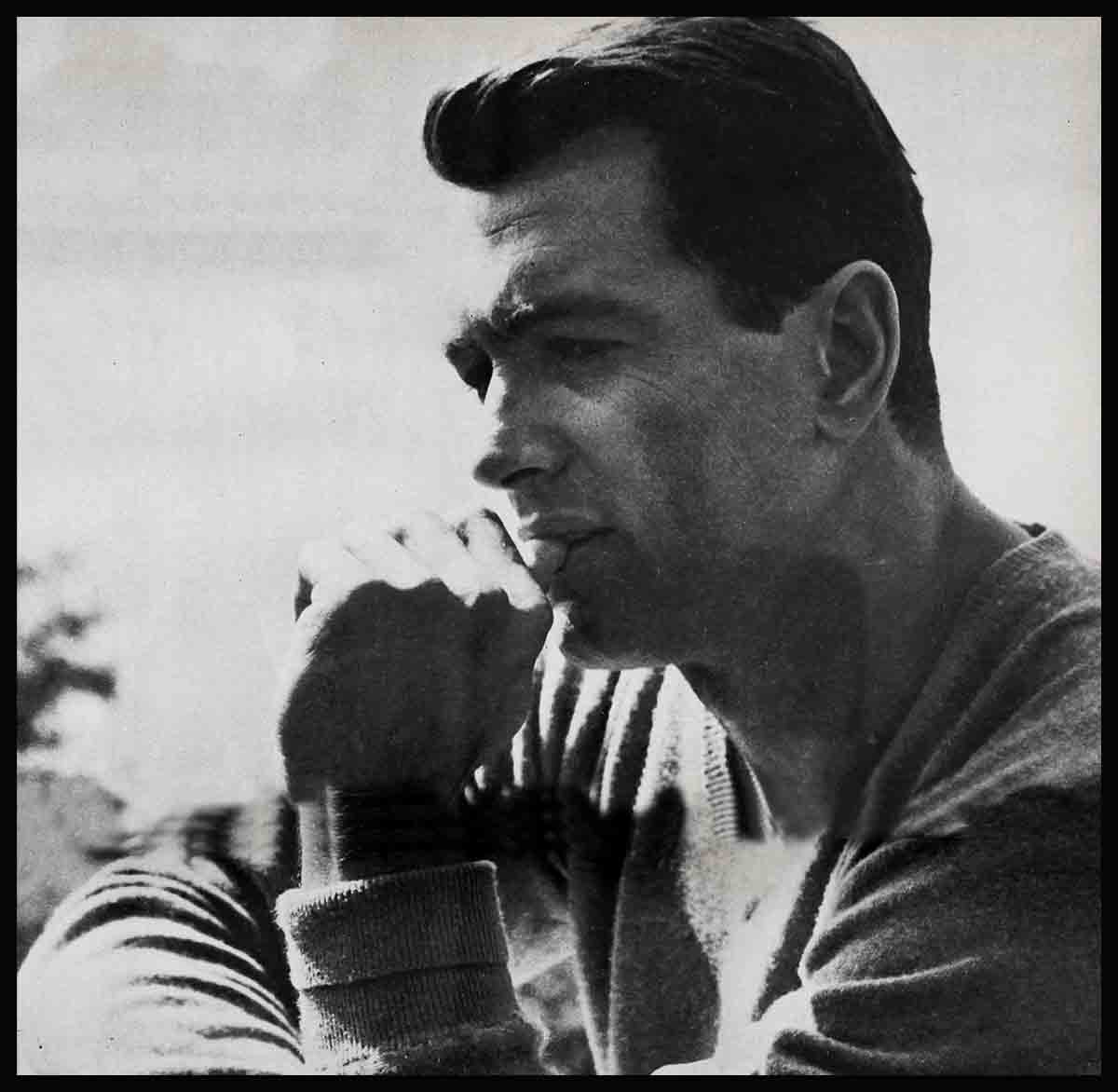

John sat for a moment, staring at her.

He put his hand on her shoulder.

And then he removed it and he put down his half-empty glass and he rose.

“I’ve got to go now, Tuesday.” he said, gently. “It’s getting late.”

“Yes, I guess it is,” Tuesday said, rising too.

She tried to smile again.

“I hope I haven’t ruined your evening,” she said. “I get like this every once in a while. . . . I’m sorry.

“You haven’t ruined anything,” said John.

Tuesday walked him to the door.

“Will I see you again, John?” she asked, as he was about to leave.

“I don’t think so,” said John.

“Whatever you say, Tuesday told him. . . .

Some sort of spell

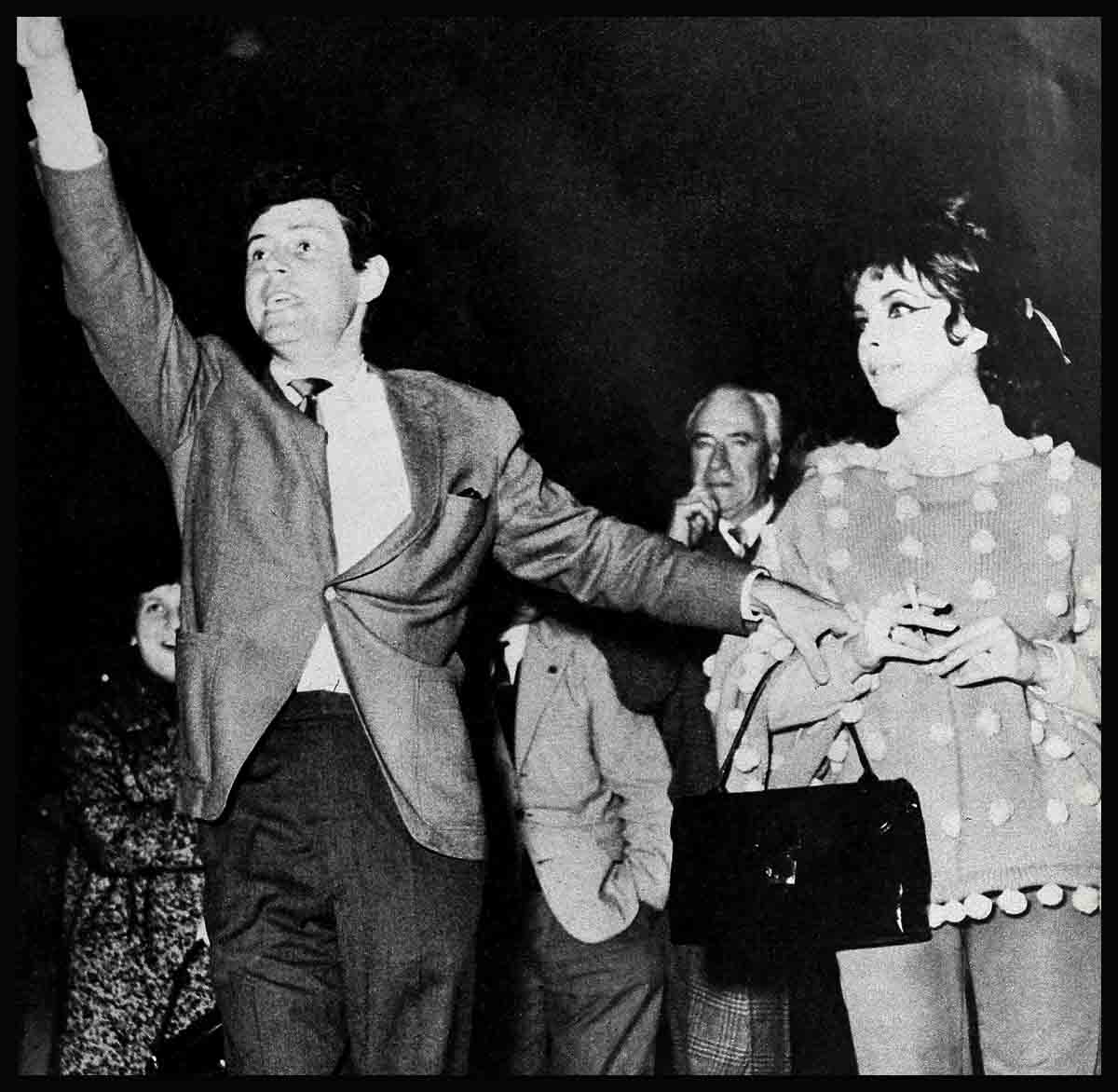

“He phoned her two days later,” say friend of John’s. “It was as if Tuesday had cast some sort of spell on him, and he hadn’t been able to shake it. Anyway he phoned and she invited him over is dinner—chili con carne and salad—and they spent the rest of the evening sitting out in the garden, talking.

“The next day. John told me: ‘It’s unbelievable. This girl is so sharp. so brilliant. I think she’s the most fascinating person in Hollywood today. She loves life. and she has the guis to be herself. She’s lots brighter than lots of women I know two and three times her age.’

“It was obvious to anyone who ever saw them together that Tuesday was wild about John. I, for one, think that by the time summer came around (Tuesday was sixteen by now), John was in love with her, too.

“Their fling was a surprisingly secret thing for a while. Actually quiet might be a better word. Except for a few friends and the inevitable under-the-counter gossip set who find out all, there were relatively few people who knew what was going on between them. During this period, Tuesday and John were two supremely happy people.

“For Tuesday, the girl who had loved to brag about her early dating, her constant dating, this was the first real romance of her life. She convinced herself that it would be first, last and forever. She idolized John—his looks, his brain, his spirit. My thought is that in John she had found not only the one man in the world with all the strong physical attractions and the powerful individual personality that she could so easily fall in love with—but that she had found, too, unconsciously, the father who had been taken from her as a child, whom she’d always been seeking.

“As for John during this period, well, he was having fun again, for the first time in a long time Career-wise, finance-wise, things hadn’t been going too well for him these past few years, and he’d been depressed. Now, in Tuesday, he’d found a girl who could stimulate him, cheer him up. She was, very often, full of mischief, full of kooky ideas—and John went along with them, happily. He learned how it felt to really laugh again. He began to get the same kick out of life that he’d thought had gone from it, for good. For this reason alone, an observer could see how he might easily have fallen in love with Tuesday.

Interestingly, Tuesday’s mother, Mrs. Aileen Weld, was fully aware of what was going on between her daughter and John, and she gave her unqualified approval.

“John’s very protective,” she said. “He’s the kind of a man a young girl like Tuesday can look up to. He’s enough like her so that she can feel as though he’s one of her own—yet he’s old enough to know how to handle her.”

And so it went, all happy and well for all concerned, right through the spring and summer of last year.

Swipes at Tuesday

But then, in September, the whole thing was ended suddenly—by John.

“He did it to protect Tuesday,” says one friend. “You can’t keep a relationship like theirs under wraps forever—and gradually word of them began to get into the papers. The writers all seemed to think that John’s position was ‘amusing,’ but they all took swipes at Tuesday. (A typical bit of reportage: Tuesday Weld is becoming a name in the American Cinema. She seems to have everything it takes to make it big on modern Hollywood standards—good drinker, lives it up and is only sixteen. Now if the kid can only get in a real good scandal, she’ll be one of our great stars.) John didn’t want to see her career wrecked. He knew how basically important it was to her, this girl who’d known little else but work since the time she was a baby. So he decided to get out of her life—pronto.”

“It dawned on John one day,” says another friend, “that much as he loved Tuesday, the thirty-year difference in their ages was too great a difference. There was a time he’d talked of marrying the girl, the hell what anybody might say.

“But now he realized that it probably wouldn’t be that easy in the long run-for either of them.”

Some people insist that John didn’t eve say good-bye to Tuesday.

Others will tell you that he phoned started to tell her that he’d decided to go to Europe—immediately, and that he hun-up on her when she started to cry and plead with him to let her see him again.

At any rate, he left.

And everyone waited to see how Tuesday would take the shock of his leaving. . . .

That television interview

It was two nights later when, a few minutes before program time, she showed up at the television studio.

Paul Coates, the interviewer, looked a her once, and then again.

The girl was barefoot, her hair was uncombed, she wore a low-cut dress that has since been described as a “burlap nightie”; she appeared to be lost, as if in a trance of some kind.

“Miss Weld?” Coates asked.

“Yes,” said Tuesday.

“Is this a joke?” asked Coates.

“What do you mean?” Tuesday asked.

“Do you always dress this way for TV appearances?”

Tuesday shook her head, slowly. “No,” she said. “I was home. It got late. This is what I was wearing. This is the way I decided to come . . . You look upset. You are. I hope it’s not my fault. . . .”

On the air, a little while later, Tuesday upset Coates even more.

She stuck a piece of hard candy in her mouth as the program began, and she sucked on it throughout.

She fiddled endlessly with the straps and hem of her dress.

She spoke softly, mumbled her answers and, more than once she took up to a full minute to decide that “I really didn’t understand that question.”

At one point, when Tuesday did understand the question, the dialogue went like this:

COATES—“Would you ever like to settle down and get married?”

TUESDAY—“No.”

COATES—“Why not? Don’t you want to have children someday?”

TUESDAY—“Huh-uh. I don’t want kids. I don’t like them. Not me.”

And Tuesday began to smile strangely . . . for deep in her heart she knew she was telling the truth, that somewhere along the line something had happened to her that had destroyed the basic instinct of womanhood for a mate and children. She knew, in her heart, that whatever else—whatever kicks were in store for her—she would always remain unfulfilled.

THE END

Tuesday’s seen in BECAUSE THEY’RE YOUNG, Columbia, and THE PRIVATE LIVES OF ADAM AND EVE, U-I.

It is a quote. MODERN SCREEN MAGAZINE FEBRUARY 1960

No Comments