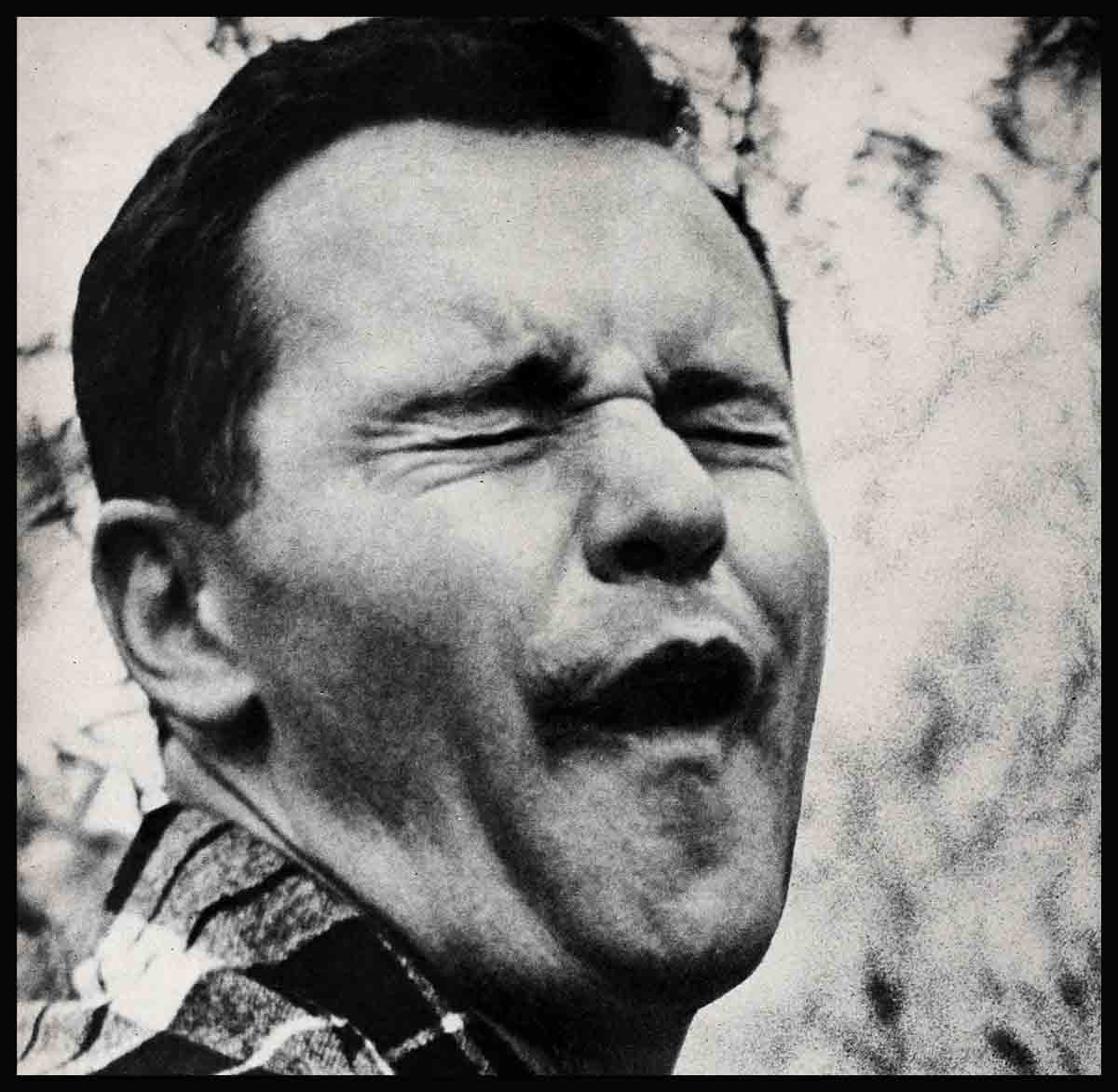

He Inherited The Mirth—Jack Lemmon

Jack Lemmon says, “I’m the luckiest guy in the world! I started out in Hollywood with six top parts in a row, top scripts, top co-stars and top producers and directors. I fell in love with a wonderful girl, Cynthia Stone. She fell in love with me. There was no problem. We were married. When we came to Hollywood, we immediately found the right home, our furniture from New York fitted into it perfectly. We wanted a baby. We got the most wonderful baby in the world, Christopher, an alert and handsome child.

“Not that I’ve had an enchanted life complete with halo,” Jack explained. “I’ve worked hard at my profession. It took a lot of courting before Cyn said ‘yes’ and she had a pretty rough time when Chris was born. But no matter how much ability, how much desire to do everything well, it always takes that extra quality—the right time at the right place and the right breaks. In other words, Lady Luck. As long as she’s in my corner, I’ve got sense enough to be plenty grateful for that!”

What Jack says is true. Luck can make or break a man, but it would be unfair not to consider his personality, determination and charm. All of which have a lot to do with his happy life. Another lady, Mildred Lemmon, was in Hollywood, too. Jack’s mother surely would be the one to ask just how lucky Lemmon was.

“Lucky?” echoed Jack’s vivacious mother one day in her borrowed Westwood apartment. A temporarily transplanted Bostonian, she was enjoying to the hilt the pleasure of her son’s success, renewing her friendship with Cynthia and getting acquainted with her one and only grandson, Chris. “Jack’s always looked for good points in people. Maybe that’s why he says he’s lucky. Since he was a baby, he’s expected the very best of people and places and it’s helped him to receive the best,” she ex-plained. His optimistic outlook on life has carried him over the rough spots, while his sensitivity toward others and curiosity didn’t leave much time for him to nurse his own introspective wounds. She stopped and smiled suddenly. “I sound prejudiced, don’t I? And I am—a little. For besides being Jack’s mother, I feel I am also his good friend. Our friendship is what makes this stage of our lives so much fuller than the usual mother-son relationship. Jack charmed me out of a swat to his impudent seat when he was two years old and his grin hasn’t changed in effect a bit. He’s still just as interesting.”

Mildred Lemmon’s blue eyes slowly left the present and started reflecting on the past, back to before the beginning. It all started in a Boston hospital elevator. Mildred Lemmon stood patiently next to her big handsome husband, John Uhler Lemmon II, while repairmen frantically tried dislodging their stuck elevator. It had stopped on its way to the delivery room. In an attempt to keep his wife calm, John Lemmon made near-hysterical jokes and told shaggy-dog stories for nearly an hour. The elevator was repaired just in time for Mildred to deliver her son, John Uhler Lemmon III, in the proper room. Perhaps the elevator was an omen. From that moment on, life for young Jack was a series of ups and downs.

“I guess Jack was lucky,” Mildred Lemmon mused again. “It all depends upon how you look at it, I suppose. If you call it lucky that he wasn’t dead before he was seven. That he didn’t have his foot cut off or wasn’t drowned in mud when he was five, or break his neck when he was four—all natural outgrowths of childhood curiosity—then yes, you could call him lucky!”

“I guess Jack was lucky,” Mildred Lemmon mused again. “It all depends upon how you look at it, I suppose. If you call it lucky that he wasn’t dead before he was seven. That he didn’t have his foot cut off or wasn’t drowned in mud when he was five, or break his neck when he was four—all natural outgrowths of childhood curiosity—then yes, you could call him lucky!”

Big Jack and Mildred found their little bundle of charm had the sensitive fingers of a safe cracker when he was ten months old. Later, they would be glad, for those fingers led to high accomplishment on the piano and a talent for composing. But that night they were only amazed at his dexterity. They took him along to spend the evening with another young married couple. Fortunately, their host had a crib—a white iron, old-fashioned one with heavy duty bars to keep Jack safe from harm. After appropriate admiring chucks under the chin, the two couples retired to the living room for the evening. Twenty minutes later a crashing cacophony of clashing iron, followed by a highly indignant howl, sent them racing to the bedroom. The bed had collapsed and in the center sat the roaring Jackie waving his fists in the air. He was holding tight to the nuts and bolts he so diligently had found and unscrewed!

“He was a little young to be taught the laws of gravity,” Mildred recalled, “so we made a mental note to watch his pioneering instinct more closely. But he was quick, thorough and quick. When he was a year and a half, we took him out to the rock garden to take his picture. He was very sweet about it and let us take some adorable pictures. Then we turned our backs. Fifteen minutes later we found him. Crawling through the shrubs to the driveway, he had discovered the tires on his uncle’s car—also the valve that let the air out. He managed to have all four tires completely flat before we caught him.

“Remember when ‘Chloe’ was the song? Big Jack and I had the record and we sang it a lot. Little Jack was two then. One day he was out playing. It got cold. He pounded on the door. No one heard him, so he kicked a pane of glass out of the door. That I heard. When I ran into the room, there was his little head sticking through the bottom of the door. He looked up at me and crooned with the most ingratiating charm, ‘Chloe.’ I couldn’t help it; I just opened the door for him and laughed until I cried. It was one of his first words and he used it at the right time in the right place. He was lucky that time.”

It was inevitable that Big Jack and Mildred’s senses of humor would rub off on their offspring. Big Jack is a jovial, dynamic past master of the art of storytelling and dialects. Then, as now, he loved the theatre and played benefits for fun. His soft-shoe dancing was often compared to Bert Williams’ and it wasn’t long before he had Little Jack working benefits with him. Mildred has a quick, impromptu kind of humor. She sees the funny side of most situations and imparted that ability to her son. Her only claim to theatrical ancestry was her mother’s half brother. He was a Frenchman named LaRue who took the stage name Jimmy O’Toole.

So it was understandable that before he was three, Jack had an uncanny knack for mimicry. When he was brought down for a nightly ‘hello’ and ‘goodbye’ with guests, his parents trembled between laughter and fear. Little Jack would look up solemnly at the guests, do his duty by Emily Post and then step behind them and do a devastatingly accurate aping of the Lemmons’ guests.

“He was so active then, I started tying him to a tree in the yard with a long rope. “But,” grinned Mildred, “I was told that it was cruelty to children, so we had a huge and very expensive fence built to keep him in. A few days after it was up, a neighbor called me in panic. She was watching Jack out the window. He had dug a hole under the fence and was crawling along a ledge two stories above the cement driveway next door. He was calling on Julie, the next-door baby. I grabbed a cookie and crept up the stairs. Very quietly I coaxed him, just as you would a puppy, ‘Come on, Jackie. Cookie—Cookie.’ He tossed me a surprised grin at the prospect of some food and nonchalantly crawled back around that two-inch ledge. When I got my hands on him I shook him until his teeth rattled.

“He never was afraid. He was always so interested in what was going on, he never thought of himself. When he was four and a half, an eighteen-year-old boy was chopping logs near our house. Jack went out to investigate. The eighteen-year-old dared him to put his foot on the log and let him come as close as he could with the axe. Little Jack promptly put his foot on the log and the eighteen-year-old swung with the axe. I’ll never forget that first scream of pain. Because his sneakers were too long for him, he lost only half of his middle toe and the end of the shoe. It easily could have been half his foot. There was no more practice of the soft-shoe dancing for a while in our house.”

Soon after that, little Jack’s life became a nightmare that eventually forced him to develop his other talents. It started with his insatiable curiosity. Mildred caught him with his head practically down the throat of a neighbor boy. His interest was clinical. He was watching the boy’s throat while he coughed. The boy had whooping cough. Jack caught it. It was a miracle that after three mastoid operations, Little Jack was alive and could hear. Five times, too, his adenoids were removed and five times they grew back.

“From the whooping cough on, it was more than luck; it was a miracle,” Mildred Lemmon said soberly. “He knew his first fear after that. The first time we took him to the ocean, he screamed himself into hysteria. He was the same when he heard a motorcycle. We finally understood that both sounded like the roaring in his ears that he experienced when he went under ether for his operations.

“Then he ran away from Mother’s house in Baltimore while we were visiting,” she smiled. “A motorcycle officer found him and he rode back majestically with no more fear of the roaring.

“He still wasn’t too strong, and baseball was about his only sport. We started giving him piano lessons at that time. It almost killed him to practice. He would sit there in his baseball cap with his bat beside him and struggle through the exercises. After two years he played ‘The Moonlight Sonata’ beautifully—by ear. He also started developing his natural talent for painting.”

The illness hadn’t restricted his sense of humor, however. He still mimicked everyone and played benefits with Big Jack. They took him to his first movie. He saw Mae West, a newsreel, and a short on snores. As the lights went up, Little Jack in deep concentration gave a loud stentorian snore. The laughter and craning of necks surprised and pleased him. After that Mae West, Mussolini, Hitler and a series of snores were added to his repertoire.

“He wasn’t always laughing and on the go,” she said, breaking her train of thought. “He was a deep thinker even as a little fellow—and sensitive and generous. He gave away toys; brought little boys and girls home. I remember one year when he was at Tabor Academy for the summer. We decided unexpectedly to take a cottage at Wolfeboro in New Hampshire. So I called and told him he could stay at Tabor’s or come to the cottage. He loved Wolfeboro so he decided to join us. ‘Min,’ he asked plaintively, ‘may I bring Jimmy home with me? He’s very poor and he can have his mother call you for an okay.’ I didn’t see how a poor boy could be at Tabor’s, but I said all right. The next day I received the call from the mother.

“ ‘What’s is all this about my son Jim spending the summer with you? I’ve just brought my other children back from Europe and Jim only now told me.’

“Poor little Jimmy O’Riley spent the summer with us just swimming in money.”

Incidentally, Jack called his mother Min from the day he discovered Andy Gump’s wife in the comics. Min she was and Min she is to Jack. On his first trip home from Phillips Andover Academy, he surprised and delighted her with a piano rendition of her favorite song, “Deep Purple,” replete with trills and frills (by ear). He was fourteen and beginning to take a serious pleasure in his music and his ability to paint. That year, Andover put two of his paintings on exhibition. One was an oil painting interpretation of Cole Porter’s “Night and Day.” The other a cartoon-type portrait of a big, roly-poly German. He had good offers on the paintings, but he saved them for Min.

“It was after doing Andover’s musical play that Jack decided once and for all to be an actor. During the summers after that he played in summer stock at Marblehead and in New Hampshire. His decision did not sway him from his practice of skimming through classes with barely high enough grades to go on to Harvard. But it won him his own personal masters degree in the art of enjoying to the fullest all of his extracurricular studies: music, drama, wrestling and track. He was too light for the football team, so he took over the management of the team. He was always so busy and -had so much energy it was hard to keep up with his activities. I think,” Mildred said thoughtfully, “if Jack ever lost his zest for living and learning, he’d just shrivel up.”

Next to acting, fishing was Jack’s greatest pastime. Wolfeboro, New Hampshire, memories come back to him as the best of “the good old days.” When he was thirteen, he and his best friend, Peter Lyon, got up at five every summer morning, bicycled to Moody’s Pond and gathered the biggest pond lilies in existence. By eight they were back in town selling the lilies at two for a nickel. By nine the teenage tycoons would take their haul of sixty cents and invest in fishing worms and spinners and spend the rest of the day fishing in the lazy New England waters.

The only time Jack wavered on his decision to be an actor was when he and Peter had a chance to become assistant game wardens in Wolfeboro. They were seventeen. It would have been a life of pure simple pleasure, with none of the gambling odds of the theatre. Peter signed up. Jack, reluctantly, stuck with his original decision. Pete is now happily married, a father many times over and the game warden.

Jack was always in a hurry. He received his BA degree at Harvard in two years and two months under the Navy’s V-12 program and had a commission in the Navy before he was twenty-one. His rush through Harvard didn’t stop his ambidextrous nature from enjoying, again, all the extras.

“I didn’t even know he was up for president of the Hasty Pudding Club or vice president of the Drama Club until it was all over. Jack knew me so well,” Mildred smiled, “he knew Id have it all over Boston before the vote. Although he was a dreamer, he had the patience to wait until an honor was a fact before he talked about it. Sometimes I could have shaken him when he’d toss them casually into a conversation, and wait for my double take. Like the time he mentioned nonchalantly that he was going to work with the Abbey Players in Boston during the summer. It took me two minutes to realize what he had said!

“Even while writing and directing the musical revue for the Hasty Pudding Club, Jack didn’t ignore the distaff side of the race. He was always popular and enjoyed dating,” Mildred explained. “While he was home from school, the phone rang constantly. He was never lonely. Sometimes it was difficult for him to find the aloneness that his deeper nature demanded. That’s when he would take off on a fishing trip.”

It was at Harvard that Jack found an alley just large enough for his Model A Ford. The police had had an uncomfortable habit of chasing his sputtering vehicle that sounded like the answer to an atomic blast. He admitted that the constant backfire might disturb the peace. He used the narrow alley as a tactical weapon. When the police cars started to converge, Jack would whip into the alley, where they couldn’t follow, splutter through every narrow street he could find and end up on the other side of town. However, the jalopy stood him in good stead in the dating department. Once he chased a girl all the way to Connecticut. Now he can’t remember her name, but he remembers the fun of it.

One of the few times Jack lost his temper was about a car. He was fourteen. He thought Min was out of the house, so he took her car and started driving up and down the street. She was home. As he pulled up in the driveway, she stepped out and suggested in firm tones that he would wait until he was sixteen to try driving again. She had startled him and he got mad. Being a clever mother she decided to ignore the ferocious muttering he did all over the driveway.

“When he was sixteen,” Mildred groaned, “we gave him my car. He turned my Ford couple into a collegiate nightmare—green wheels, red spokes, a devil thumbing his nose on the windshield—the works. He sold it suddenly for a fraction of its worth. He always got taken on money deals, but he was long on diplomacy. He sold it to the son of the cop who had been chasing him all over town!”

The Lemmons were again nonplussed when their offspring decided that opportunity was just around the corner—of 55th Street in New York—after graduating from Harvard. This lucky break was in the form of the Old Nick’s and it offered twenty-five dollars a week, plus the chance to write shows, m.c., sing, play piano and wait tables. To his surprised parents, he explained that he was having the ideal breaks—a chance to be lousy! Some nights he would lay an egg, other nights the customers would love him. He learned the intrinsic value of instinctive showmanship, quite often on an empty stomach.

“Big Jack, who is vice president of the Doughnut Corporation of America, took the entire national convention to the Old Nick’s to see his son. The management went crazy. They completely filled the place and Jack will never have a more appreciative audience. A few nights later my nephew went in to see Jack. He asked the hostess about Jack and she just groaned, ‘Oh, not another relative!’ He did learn a lot there, but he worked to learn it. One thing that nobody mentions about Jack,” said Mildred with justifiable pride, “is his writing ability. He’s written some beautiful things—not just music. When he was on Midway as an ensign, he wrote some of the most beautiful letters I’ve ever seen. I’ve kept them. Some day I think Jack will take the time to write—plays, scripts, and maybe a book.”

It would seem that Lady Luck has had quite a bit of help in making Jack Lemmon’s life a success. A myriad of natural talents, plus the innate desire to develop them, plus the ability to make things happen have given the Lady quite an assist.

“I guess you could say Jack was lucky,” Mildred said slowly. “He was lucky to have a good education and the right breaks in his personal life and career. Yet, looking back over the pattern of his life, I do feel his desire to work at everything, his joy in living and his boundless, busy curiosity and energy are the basis for his success. What’s the old saying? You can’t keep a good man down. That’s Jack. Luck or no luck, I think he’ll continue to work his way to happiness.”

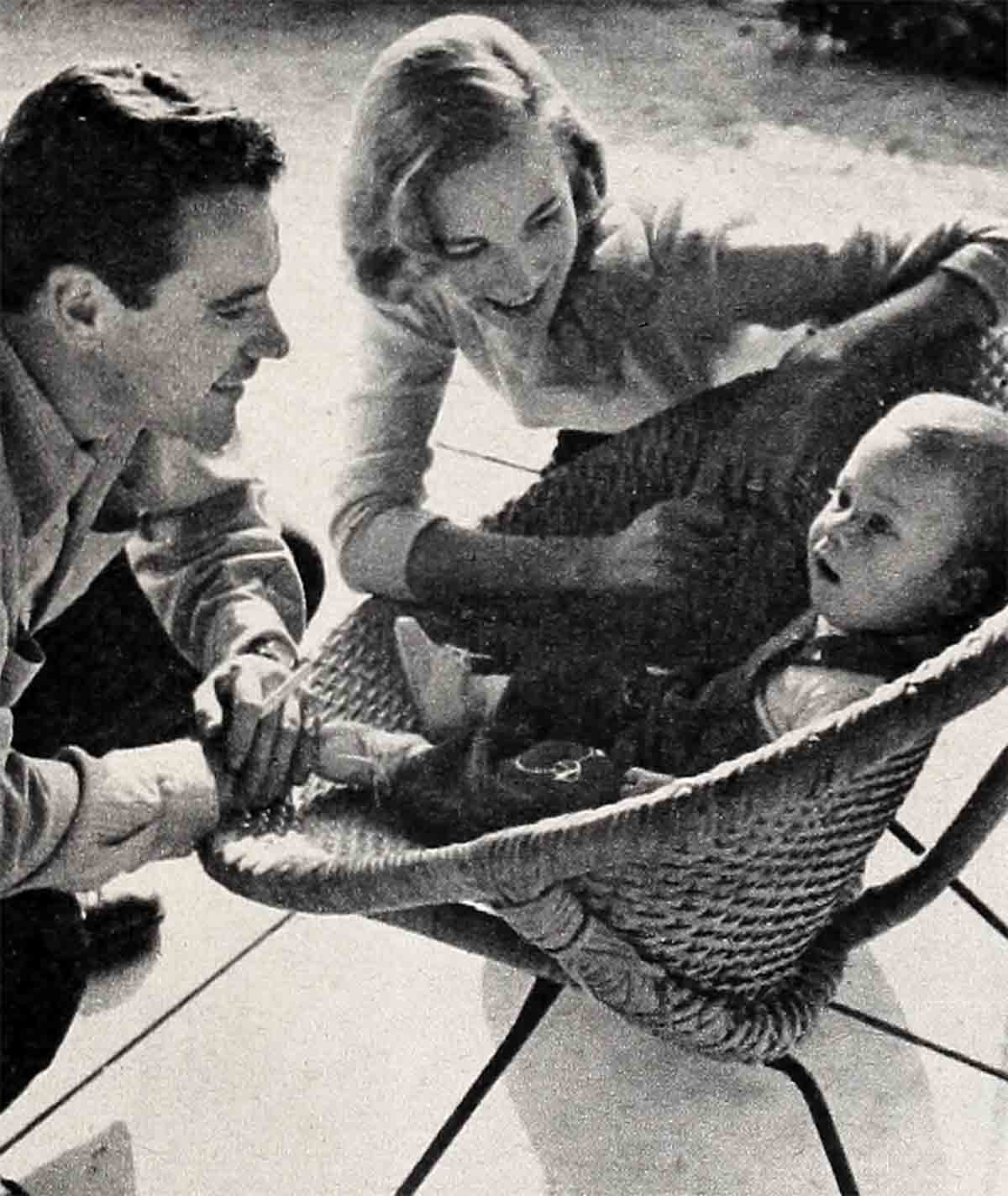

It is understandable that Jack feels he’s the luckiest guy in the world. He has a home full of love and fulfillment. Cynthia is not only a wonderful wife and mother, she is a part of his professional world. He is looking forward eagerly to her re-entrance into acting. They share the pleasures of parenthood as they watch Christopher do all the brilliant, adorable things that only your own child does. They also share an outgoing interest in others. Cynthia has been working with the Salvation Army Girls’ Club, conducting classes, first in charm and now drama. Jack has become interested, too, and they spend hours working with the girls and tape recorders. The girls eat it up and they are learning poise and self-assurance while they play.

Cynthia is a fine female foil for Jack. In his very rare tempers he has a habit of blithering and repeating and she has a habit of laughing at him. Aware that he is not at his best in a snit, her laughter brings him out of it fast. Her sensitive antennae can spot his rare moodiness and a wisecrack at the right time and right place lifts his occasional depression.

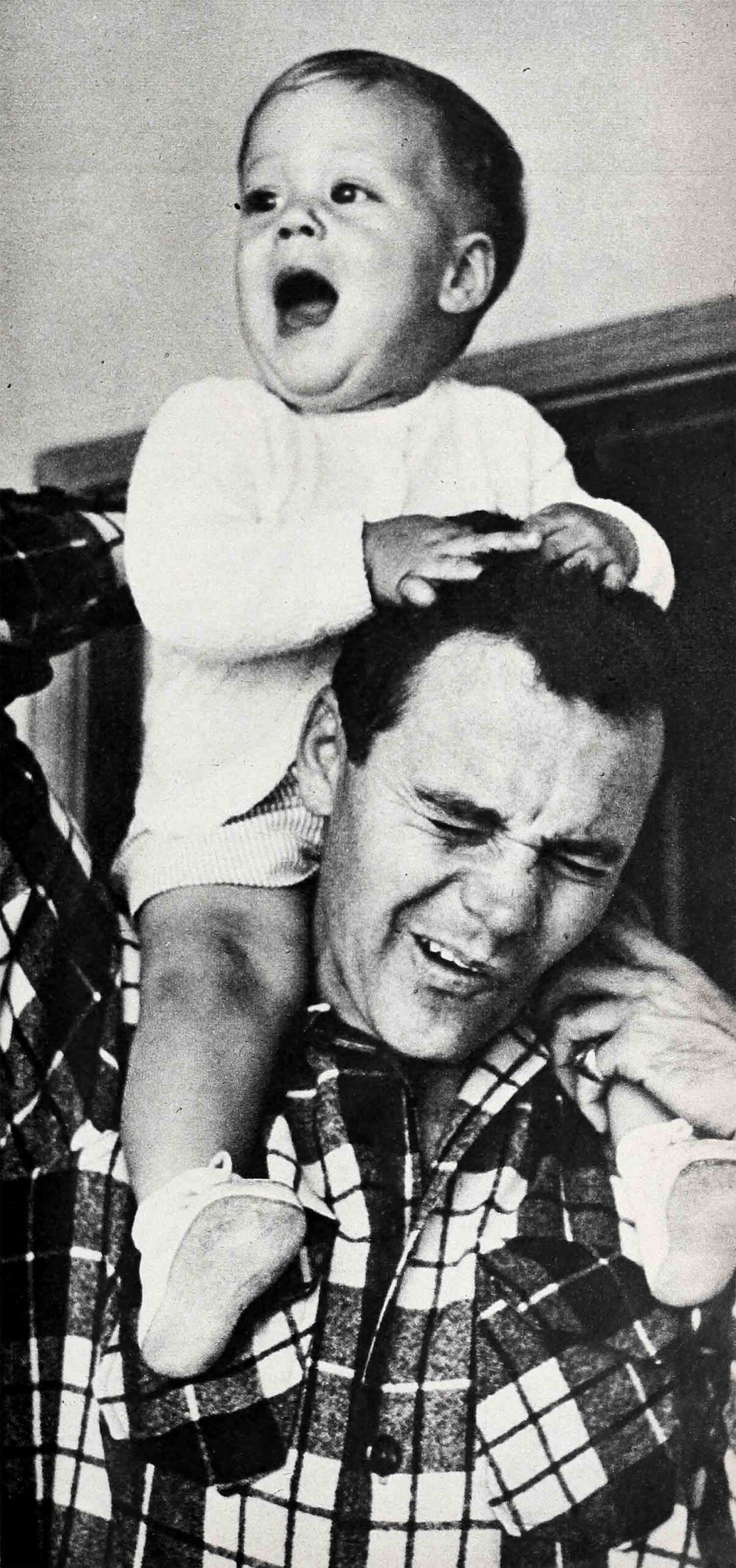

Chris, barely one, is already showing signs of his father’s insatiable curiosity and his mother’s good looks. He, too, is a busy, busy boy—and yet sensitive. An oil portrait of Cynthia as a little girl hangs in the hall. Chris loves it. He makes small talk with the little girl in the painting and probably has explained to her why his parents roar with laughter when he is wearing his Davy Crockett coonskin cap.

“I couldn’t have it any better on the home front,” Jack reiterated. “Career-wise, six comedies in a row make it only natural that I’d like to get my teeth into a good dramatic role now. I’ve been awfully lucky. I’ll stink one up eventually. Any actor who thinks he won’t is crazy. The better the actor, the more he louses when he does. I used to walk into the Players Club in New York and meander down the hall with the portraits of the great lining it. Under each portrait were the most stinking reviews on colossal flops imaginable. I’ve always remembered that he very best have goofed at least once.

“And I also remember,” Jack said seriously, “that there are at least fifty actors that I know personally, who could have done as good a job as Ensign Pulver in ‘Mister Roberts,’ as I did. They didn’t have that lucky break—timing. Being in the right place at the right time. I was there; I was lucky.

“ ‘Mister Roberts’ was my first away from Columbia. When it conflicted with Columbia’s ‘My Sister Eileen,’ the powers that be worked it out so I could do both. I couldn’t ask for any better breaks.”

Jack’s cautious appraisal of his performance in “Mister Roberts” is not abetted by the directors and co-stars with whom he worked. Turning in the most hilarious comedy performance to hit the screen to date, his co-workers give high praise to his talent—not his luck. Hollywood is fully aware that Jack is one of the big talents that will consistently ring the bell of stardom for a long, long, time, for he is an actor first and a star second. No one, except Jack Lemmon, feels he is Lucky Lemmon.

THE END

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE SEPTEMBER 1955