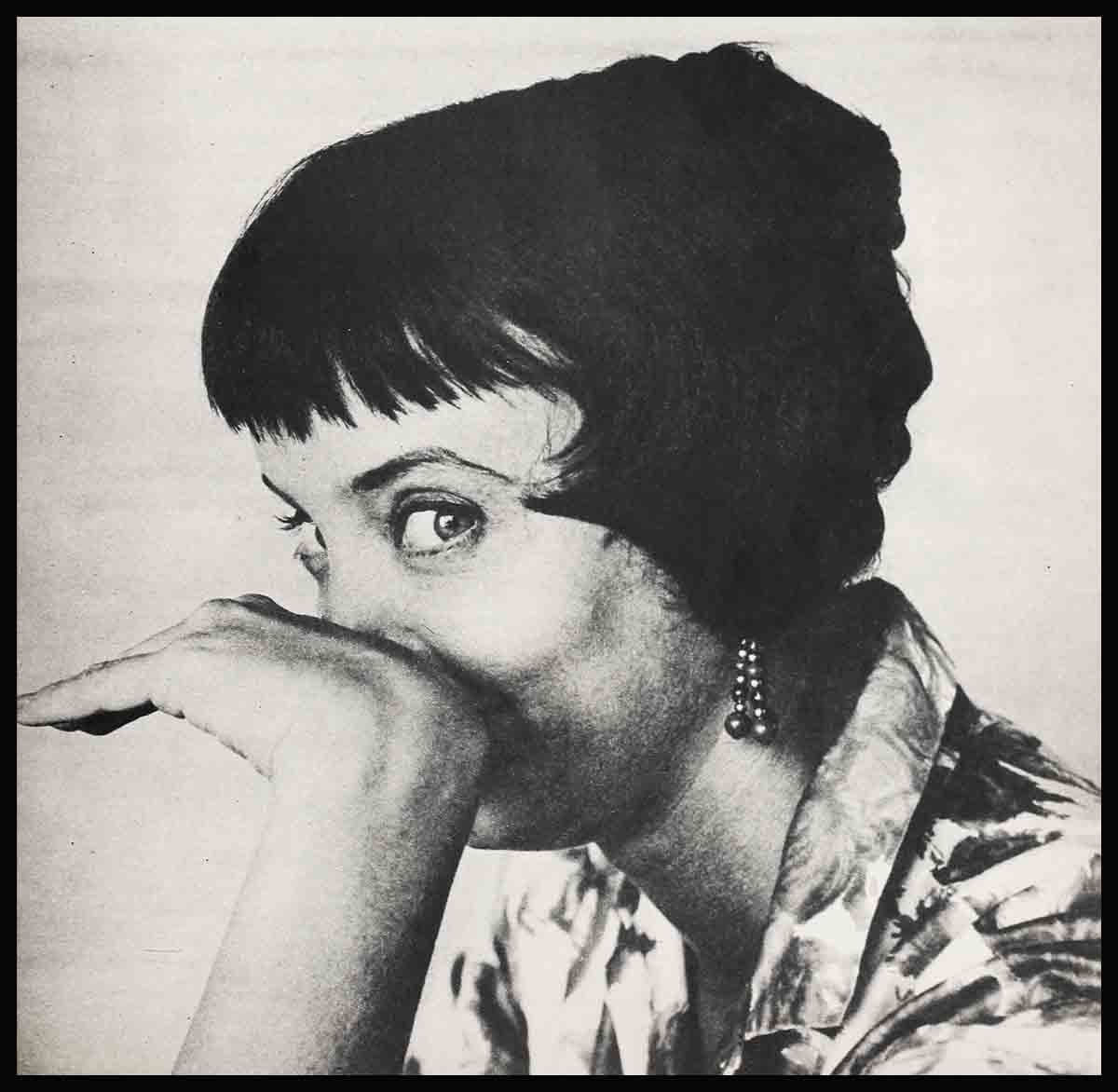

Along Came Carolyn Jones

Circumstances had conspired to give young and talented Aaron Spelling too good an opinion of himself and too poor an opinion about women. His outlook, B.C. (before Carolyn), is best described in his own unsparing words.

“When I was at Southern Methodist University in Dallas,” he grins. “I won a cup once for being the most selfish member of the student body. It was the MCBOC trophy—awarded to the Most Charming Bounder on Campus. Only it wasn’t pronounced bounder. People used to say to me, ‘You’re the most selfish, self-indulgent so-and-so I’ve ever known. I don’t know why we like you.’ ”

Part of that irresistible charm rubbed off on one of the SMU co-eds, and Aaron married her. With practice, she not only found out why she liked Aaron, she also discovered reasons—still vague to him—for disliking him and leaving him.

“She was a very wealthy girl,” Spelling says in extenuation of that abortive experiment in nuptial bliss. “I thought it would be very smart to marry her, since that seemed to be the easiest and fastest way to become familiar with the problems of social nobility.”

Intent upon making his mark in Hollywood, Aaron took his bride to lotus land by the sea. Having been a shining campus playwright—not to mention SMU’s irrepressible gridiron cheerleader—he expected Hollywood to fall dead at his feet. Something less than that happened. He failed acquaintance with the problems of social nobility, but his wife, unhappily, became acquainted with the problems of destitution. Aaron’s vaunted charm, six months after they said their vows, lacked sufficient glue power to keep their marriage from coming unstuck.

“I went to an interview for a job selling tickets for American Airlines, and when I got home she was gone. Her father had sent her a plane ticket to take her back to Texas. That killed what little sense of security I had. I was stuck here, lonely and broke. I was terribly hurt.”

His wife’s sudden exodus, sanctified soon thereafter by divorce, some how left Aaron with a jaundiced view of the opposite sex.

“It was an awakening period,” he recalls archly. “I found that girls can be vain, stupid, narrow-minded and bigoted. I learned that I’d been a shnook and decided to attack life.”

His method of attack was oblique. He loved to meet women who gave him the slightest excuse to hate their innards.”

“I had a tremendous chip on my shoulder,” he candidly admits. “I wasn’t in a very receptive mood to the considerateness of other people, women in particular.”

Then along came Jones. Carolyn Jones.

This was a pre-titian Jones. She was an undulating blonde at the time, with clinging dresses and cloying eyes, trying to set off sexpot reactions in Hollywood. She, too, was fresh out of Texas. No one in the film world had heard of her, and Spelling was willing to do his bit to perpetuate her obscurity.

Through a comedy of errors related at other times, she ended up acting in a little theater presentation Aaron was directing, drawing upon his unabated acting enthusiasm in college. The thing he liked about Jones was that there wasn’t a thing about her he liked. He also appreciated the fact that his hostility was cordially returned.

“I didn’t like her at all,” he affirms wryly, “and she hated me. I thought she was a pretty smart-alecky kid.”

Aaron came by this impression when his leading lady eloped two days before the show was scheduled to open. Carolyn volunteered to fill the breach. He handed her a script to read. She tossed it aside disdainfully, and proceeded to go through the whole part from memory. Spelling was more irritated with her than impressed.

“Why didn’t you tell me you had done the play before?” he snapped.

“I didn’t do it before,” she replied dryly.

“Then when did you learn the script?”

“Last night,” she drawled, “when I decided I should do it.”

She got the part, but made no conquest.

“I used to detest this girl!” Spelling exclaims. “Oh, how we used to fight! I’d tell her to do a scene a certain way and she’d say, ‘If you want it done that way I’ll do it, but I don’t think it’s right.’ I could have strangled her.”

Carolyn fed his bitterness before she quelled it.

One night after the play opened, they helped make up a foursome—Carolyn and an actor in the cast, and Aaron with another actress—at a coffee shop near the theater. The three performers fell to discussing the possibilities of being discovered by a producer or a director, and daydreamed of TV and motion picture breaks that might come out of the show.

“Then out of a clear blue sky,” Aaron still enshrines the moment, “Carolyn looked at me and blurted out, ‘Jeepers, what could you get out of it?’ We’d been fighting tooth and nail, and then that! I realized that her concern was not because it was me. It just didn’t seem fair to Carolyn.”

That unexpected shaft of integrity—if not tenderness—about took all the fight out of Aaron. From that point on, Jones wasn’t just moseying into his life. She was galloping.

Before the night was over the sworn enemies gave up swearing for endearments. Carolyn’s date and Aaron’s date had early calls, so she dropped them off first. As she started to take Spelling home in her car, he asked if she would mind stopping by at the drugstore at Sunset and Vine so he could get some pipe tobacco.

“We started going home,” he picks it up from there, “and got to talking. We drove and drove, and finally we were at the beach. It was the first time I saw it because I’d never had a car that would drive that far. We took off our shoes, and sat on the sand, and just talked. Before we knew it, it was 6:30 in the morning! We talked about everything—dreams, families, our innermost thoughts. I’d never talked to anyone like that.”

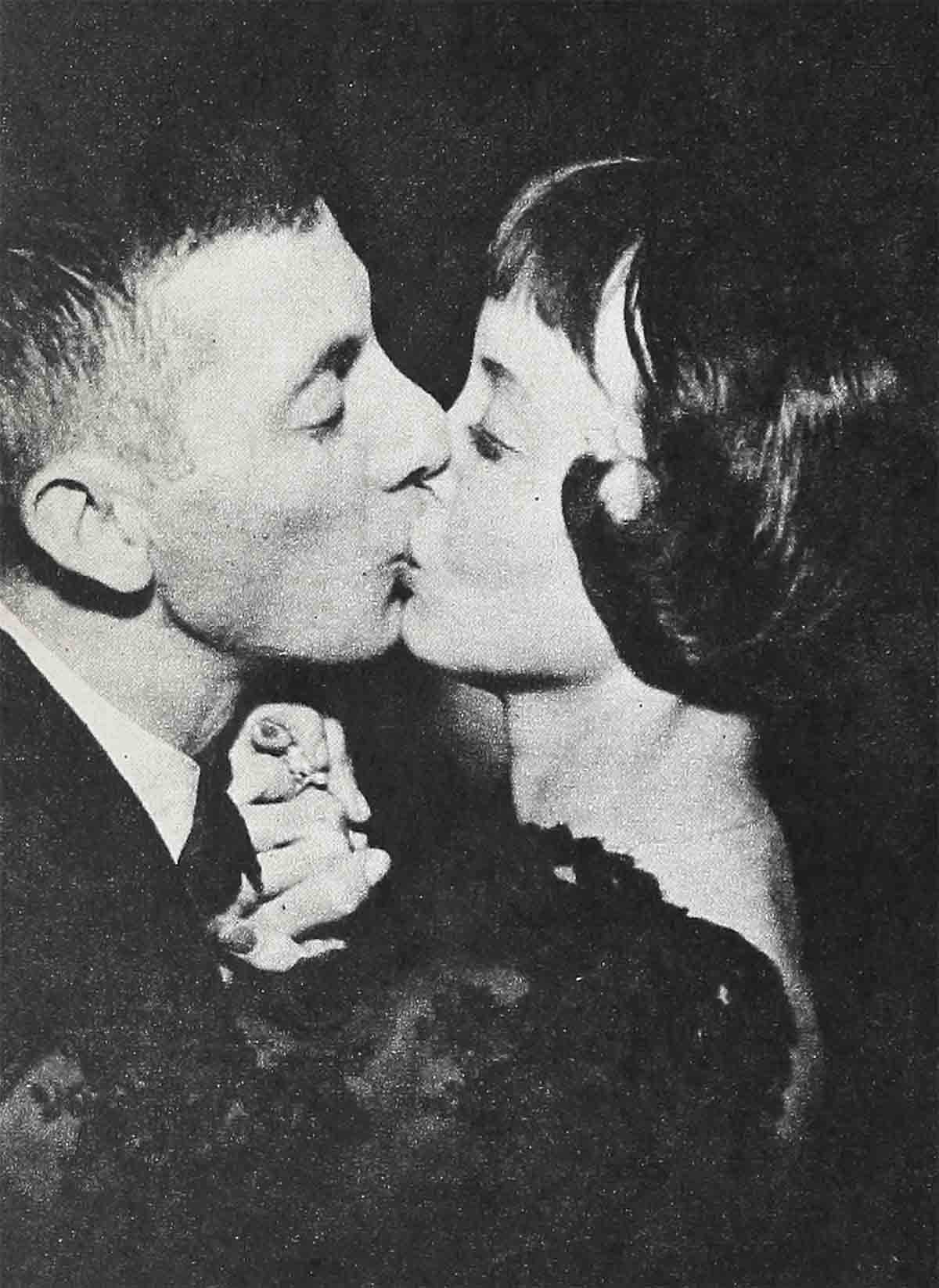

Outside his place, Aaron got out of Carolyn’s car and said, “You know something? I think I’m going to marry you.”

“You want to know something?” Carolyn said very seriously. “I think you will.”

And so—without a cent to their collective name or a nickel’s worth of future—they were married. They parlayed their love and their talent from a tiny bachelor honeymoon flat to their present brand new $133,000 mansion in Royal Oaks, which Aaron proudly quotes Carolyn describing as “Grecian modern furnished in early American money, with wall-to-wall scripts.” But what has happened to Aaron Spelling since Jones came along cannot be measured in mere real estate.

At SMU Aaron was the only American college student outside of Eugene O’Neill ever to win the Harvard One-Act Play Award for two years running. However, after the Dallas Morning News refused him a job as a college reviewer and Hollywood exhibited a disturbing determination to struggle along without his works, Aaron had despaired of earning his living that way. Carolyn restored his birthright as a writer.

Until Jones came along, he wasn’t even too sure about his manhood. His unsettling first experience in marriage certainly didn’t help. On top of that, a good puff of wind would whiff him off to Bagdad. As the writer and producer of the highly-touted new CBS-TV series, “Johnny Ringo”, Aaron has emerged a Hollywood heavyweight. But physically he’s a featherweight. He still has the appearance of a college boy roaming around Hollywood between classes. He is a soft-spoken, crew-cutted wisp of a man who looks like an upended broomstick. in Brooks Brothers clothing. On his sparse frame is mounted a twinkling-eyed owl face from which he radiates warmth, wit, wisdom and wellbeing. To hear him tell it—and he tells it eagerly and well—it was not always thus.

“Carolyn is a woman who makes a man feel masculine,” he enthuses. “Even if he weighs only 118 pounds, like me. I think this is the greatest gift a woman can have. It must be a gift. Carolyn has the gift of making you feel like the most masculine man in the world.”

To feel masculine, a man has to feel loved. To feel loved, he has to feel cared about. She cared about him as much when they didn’t know where their next meal was coming from as she does now when they don’t know where their next near-million is coming from. She not only cares about everything Aaron does; she is part of everything Aaron does. There are no separate compartments in their lives—not her acting nor Aaron’s writing and producing. Aaron prides himself upon the extent to which he has leaned on Carolyn in bringing “Johnny Ringo” to life. When I asked if she influenced him in his work, he shrugged:

“Not any more than God does!”

In his college days, Spelling was a self-contained dynamo. Along came Jones, and that was changed. Now he glories in sharing every experience with her.

“I wouldn’t pick a tie without asking Carolyn,” he declares happily. “We’ve had the strongest relationship. By the same token, Carolyn wouldn’t think of doing a picture or reading a script without me. She held up rushes on ‘Guns Of The Timberland’ for five minutes at Warners because she wouldn’t let them start until I got there. That’s unheard of!”

Carolyn was out of town when Warners wanted her for the feminine lead in “Ice Palace”. The studio got hold of Spelling and asked if he could get the script to her. He did better than that. He called her long distance, and for an hour and a half read passages to her over the phone.

“I think we ought to do it,” Carolyn said at last. “Don’t you?”

“Yes,” Aaron grinned. “I already told them you would.”

If Carolyn doesn’t influence Aaron any more than God, the same may be said of his influence on her. Aaron practically bludgeoned her into playing the existentialist in “Bachelor Party”—and she emerged an Oscar-nominated star.

“I think you have to love someone very much to know what’s right for them,” Aaron points out. “When Carolyn didn’t want to do ‘Bachelor Party’ that was our first fight. I thought she’d just explode in it, and she did. I made her do it.”

He and Caroline have taken the yawns out of togetherness.

“It’s so much fun that way,” Aaron insists. “If I go on location, she goes. If I can’t go, she won’t do the picture, and vice versa.”

Their togetherness is not a moral pose. It was forged in the early years of their marriage. There was no middle ground. Having each other had to be enough or too little. There was nothing else. The erstwhile college playwright was an intimidated writer, a sometimes drama coach and director, and a starving bit actor.

Along came Jones—and they starved together. It was better that way.

“Our wedding party,” Spelling chuckles, “was the worst of all. Our only friends were other starving actors. Eight people, including Paul Richards and his wife, were at the ceremony. We went to Paul’s bachelor apartment, where our wedding gift was a bottle of champagne. All ten of us drank up the wedding present, and then we went home—to our own bachelor apartment.”

Aaron no sooner carried his bride across the threshold than he got a long distance call telling him that his father was dying. The honeymoon was interrupted by a frantic effort to scrape up plane fare to get Aaron to his father’s bedside.

“We didn’t have a nickel,” he recalls. “We had no car. Paul Richards loaned us $25. Carolyn’s agent loaned us $25. Carolyn was about to leave on a personal appearance tour for ‘House Of Wax’, and she got Warners to advance her $200 expense money. So I went. My father recovered, and everything ended happily.”

Fortunately, hard times were not a sudden post-marriage shock. Aaron and Carolyn were bloody broke, but unbowed throughout their spartan courtship.

“When I met Carolyn,” he smiles, “I was directing a show for Preston Sturges for $100 a month—‘Live Wire’ it was called. Carolyn was working backstage at the Players Ring for nothing. Her father was dead, and her mother was in Hollywood working and raising Carolyn and her kid sister. When we got married, I got me a big job. I taught at Ben Bard’s for $150 a month. Carolyn’s mother took ill and went home to Texas. On $150 a month we were married and also raising Carolyn’s sister, Bette.”

Once Jones came along, the bitterness began to drain out of Aaron Spelling. He looks back on those lean days with affectionate amusement rather than rancor.

“We used to go to Rand’s. Round-Up where you eat all you want for $1.50,” he laughs appreciatively. “We would save up for it. I remember when $1.50 was the whole world. Carolyn still has a hangover from those days. She still gathers up all our loose change and rolls the coins in nickle, dime, penny and quarter wrappers. She does it even when she’s dead tired. She can have a five o’clock call, and she’ll be wrapping her pennies. We used to save all our change. We figured that once we got below a half-dollar our money was all gone anyway.”

Aaron and Carolyn warm themselves with remembrances of their poverty. It sharpens their appreciation of their present good fortune. For Aaron, it underscores his esteem for the girl he married.

“Once we had a car and we couldn’t keep up the payments of $36 a month,” he adds to their saga. “Paul Richards needed a car to get to the studio, so he used it and made the payments. Those hard times were the best thing that ever happened to us. Every little thing we get now we realize we’re very lucky.”

Aaron Spelling would be hard put to pick the greatest benefaction bestowed by Carolyn Jones. Certainly not the least is the fact that today he is one of Hollywood’s most successful and prolific writers. When he was fresh out of college, and already stale with failure, he was defeated as a writer.

Along came Jones, and she changed all that, too. One day Carolyn read the two award-winning plays Aaron had written at SMU, and she put a slamming halt to his career as a bit actor grubbing grocery money by playing dirty, ancient Arabs in burlap sacks, crying, “Alms for the love of Allah.”

“I don’t want you to act again,.” Carolyn was outraged at the shocking waste of talent. “Genius like yours should not be forced to traffic in fertilizer as a bit player. You have to write. This is where your future is going to be. That’s what you were put here for.”

Carolyn did not express an idle conviction for she put her deeds where her mouth was.

“Carolyn took bit parts herself so I could stay home and write,” Aaron shakes his head, still incredulous at the way she backed faith with sacrifice. “At restaurants she picked up every check during the time we were engaged to the time we were married, and most of the time after that. Never in the most fierce argument we’ve ever had has she said, ‘I paid for this’ or ‘I did this.’ She may not he perfect. There may be some things wrong with her, but not as far as I’m concerned.”

That is not a surprising bias. Carolyn was doing fairly well in television, although by no means had she attained stardom, when she had an opportunity to be represented by the powerful William Morris Agency.

“I wouldn’t think of signing with you unless you also handled my husband,” she slapped them with an ultimatum. “He just happens to be one of the finest young writers in Hollywood.”

Aaron still is overwhelmed by the enormity of the gesture.

“I don’t know if you realize what a gamble she took,” he says. “MCA had turned her down, and she tells William Morris they must take her husband! They believed her because Carolyn herself believed so much in me. The next day Stan Kamin, of the William Morris Agency, called me and said, ‘Have you ever written a Western? I think we could sell it for you.’ ”

Aaron, of course, didn’t want to let Carolyn down.

“I went home that night and wrote a Western,” he says simply. “I’d never written a Western in my life. All the movies I’d ever seen about the West looked awfully dry to me, so I wrote a Western called ‘A Crying Need For Water’. It was the first thing I ever sold! A week later I was introduced to a guy named Dick Powell. I found myself writing Westerns for Zane Grey Theater, and there it was.”

There is no doubt in Spelling’s mind about the full size of Carolyn’s contribution to his present dazzling eminence as a Hollywood screen writer.

“I don’t think I’d ever have written anything without Carolyn,” he agrees without the slightest prodding.

Aaron still was teaching for Ben Bard at $150 a month when Carolyn began getting parts at Revue Productions, and earned $250 about once every two months.

“What would it take to make you feel secure?” Carolyn asked one night.

“If we only had $500 in the bank,” he sighed deeply.

They managed to save $360. Meanwhile, Spelling had a terrifying premonition that he never would see his parents again. He wanted desperately to fly to Dallas to visit them, but he didn’t have the money. He tried, unavailingly, to put the disturbing fear out of his mind. Then one day Carolyn asked Aaron would he mind driving her to the airport.

“I’ve got a friend coming in from Milwaukee,” she explained.

“When I got there,” Spelling has to struggle to keep the mist out of his eyes when he tells it, “there was no friend from Milwaukee. My folks came off the plane! Carolyn had sent them two tickets she bought with the $360 we had saved!”

Aaron says he had no idea what compassion meant until Jones came along. He recounts another story about the time, recently, when she got a letter from a woman in Winnetka, Illinois, asking her to send an autographed picture to her ailing 19-year-old daughter, who was unaware that she was dying of cancer. The girl felt they had so much in common because her name, too, was Carolyn Jones.

“Carolyn just broke up.” Aaron relates. “She went to great pains to get the girl’s phone number, and talked to her for 45 minutes. In the course of conversation. the girl said she hoped some day to hear Carolyn sing. The next day Carolyn rented a studio. Don Durant, the star of ‘Johnny Ringo’, accompanied her on the guitar. She dubbed a record singing ‘Black Is The Color Of My True Love’s Hair’ and sent it to the girl.”

Aaron Spelling is witty and urbane. But when he speaks about his wife, he is overcome with emotion.

“Maybe this is too intimate for you to use,” he says softly, “but we go to bed at night, turn out the lights as people do, and we talk. Like last night, Carolyn said, “How can people who love each other leave each other? They many memories. Everything they see they’re going to be reminded. Suppose the girl is with another man, and they pass a dog on the street, and he says, ‘Look at that little poochie. Wouldn’t you be reminded?’ You see, one of Carolyn’s nicknames for me is Poochie.”

He never ceases to marvel over his wife.

“The depth of this girl is unbelievable,” he attests. “Most people think she’s flip. She cries at jai lai games!

Carolyn inspires him to endless wonders.

“You pick the right subject when you ask me to talk about her,” Aaron Spelling smiles. “I could go on forever. The trouble is—how are you going to stop me?”

Once upon a time in Hollywood there was a saddened, embittered young man. Then along came Jones.

THE END

—BY BILL TUSHER

It is a quote. SCREENLAND MAGAZINE MAY 1960