“Pardon My French”—Dennis Morgan

“Get down the French dictionary,” Dennis Morgan shouted, roaring through the front door, on an evening in June, 1947. “If we like this script,” he said, tossing a 3-pound document into Lillian’s lap, “your stay-at-home husband will travel this summer to Paris, France!”

Secretly, Dennis hoped he’d hate the story. He and Lillian and the three children had been looking forward to a summer of family fun.

But the script, To The Victor, turned out to be an exciting story, full of punch (an authentic picture of life in post-war France) and the role “such a departure from my usual assignments” (no singing) that Dennis said yes. Lillian agreed. The following week was spent filling out forms down at Los Angeles City Hall and at the French consulate—a passport and a French visa being required. Six days later, Dennis was on the train to New York, his luggage filled with soap, cigarettes and books on how to learn French in a hurry.

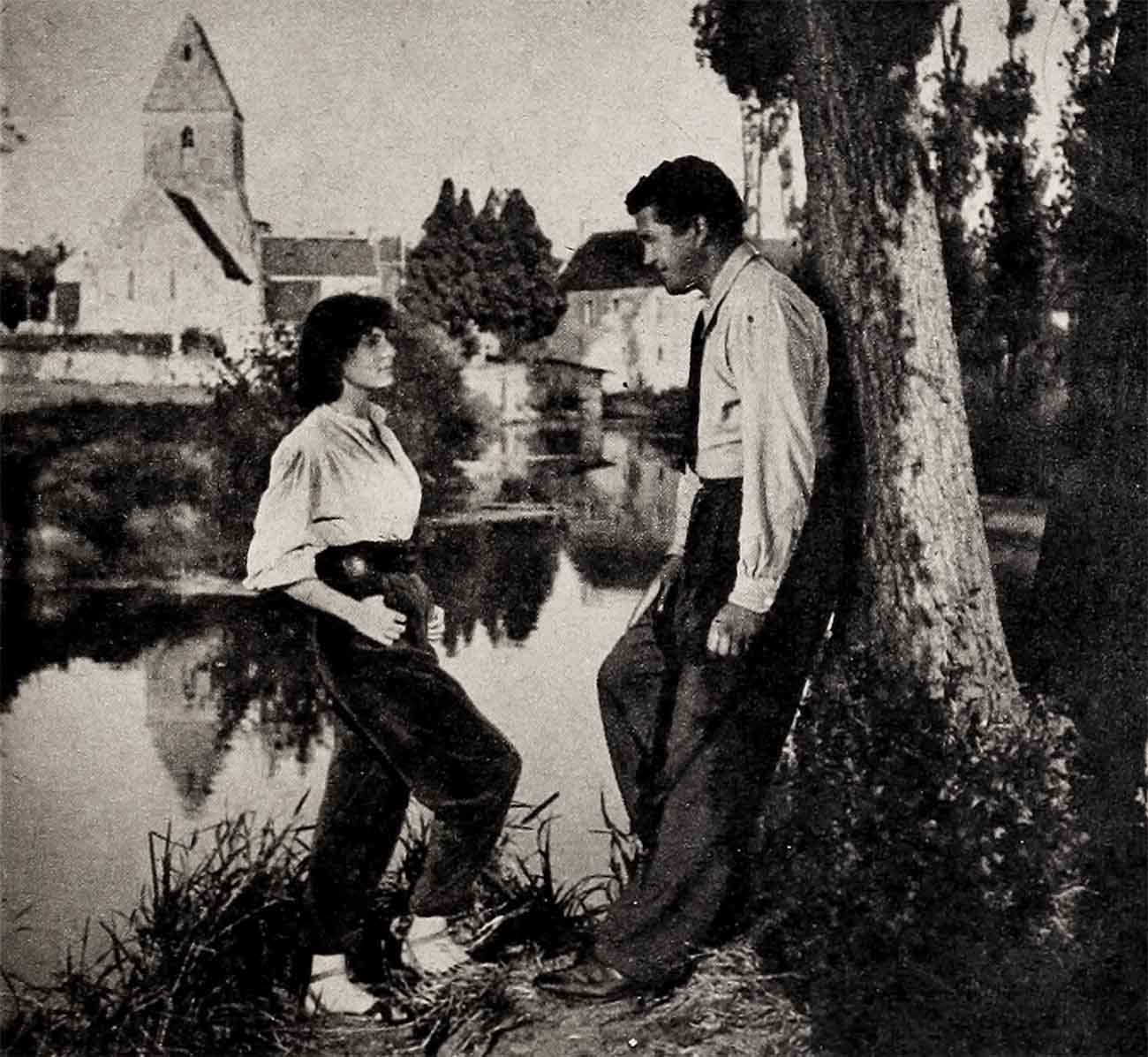

Director Delmer Daves and leading lady Viveca Lindfors—the new Swedish star—were already in Paris. The idea was to shoot all exteriors (about one-third of the movie) in France, and finish off the interiors, duplications of actual rooms in French buildings, on stage 16, Burbank, California.

In New York, Dennis caught a TWA plane. First stop, Newfoundland; second stop, Ireland; third stop, Paris. When the plane let down at the Paris airport, Dennis was still a “one-word-French-speaker,” despite the books in his luggage. (As a singer, he had learned to pronounce the language with authority, but that was the end of it.) Five minutes on French soil, and the Hollywood star found himself encircled by reporters from the Parisian dailies. They fired away and he listened hard, but this man who can sing the whole of Manon and Faust in French couldn’t make out what they were asking. “Je suis very dumb about French,” he was telling them, when a representative of the Warner Brothers’ Paris office came to the rescue.

They went directly to the hotel, the George V, which had housed Nazi officers during the occupation, and now is filled mainly with American travelers and a very few Parisians. The hotel prices are out of the reach of the normally well-off Frenchman. Dennis describes the hotel as “modern and swanky” but with certain odd features—his room was two floors above the elevator’s last stop. There was no soap in the bathrooms because there is virtually no soap in France. The only other inconvenience at the George V was the four-day dry period.

Dennis had come back to the hotel, weary and wilted, after a day of shooting in the Paris streets. The heat, 105 degrees with lots of humidity, had broken all records since the inception of the Paris weather bureau. Dennis threw off his clothes, got into the shower, turned on the spray. No water.

He called the hotel desk: “What’s up?”

A main had broken. Repairs might take several days because of material shortages. They were sorry. Dennis paced the floor for a few minutes. Then he called the porter. A short time later, a hot and grimy Delmer Daves strode in and found Morgan relaxing in a tub of six gallons of bottled water. A happy bath, even if it did cost Warner Brothers eight dollars. Daves trotted right back to his room and did likewise.

With this exception, the life of a foreign traveler in Paris was exceptionally comfortable, though expensive. In the top restaurants, meals were true to the many-course French tradition. And the wine was divine.. Back in Hollywood, Dennis had heard about European food shortages. “They’ve had a hard winter; the papers say more than half the wheat crop of France was ruined,” he told his boss, Jack Warner. “Won’t we be unwelcome, extra mouths to feed?”

Warner said no, and explained that before the war, American tourists had spent a lot of money in France, and were a large factor in her trade balance. France was now desperately short of dollars with which to buy food, fuel and raw materials in this country, and for this reason was actually anxious for tourists.

So Dennis ate his first French meal with a clear conscience. It was a fabulous meal at a fabulous price—3,000 francs ($25).

“That’s a typical price for a first-class restaurant meal these days,” says Dennis. “The ordinary Parisian can’t afford such prices since an average salary runs about 8,000 francs a week. There is practically no meat for sale in Paris except on the black market. We saw several horse meat stores, and people queued up in front of them.

The bread, people complained, was worse than. during the war—it had been taken off coupons, was back on again. Butter was rationed and wine had just been taken off in an effort to keep people’s minds off the poor bread.

Gas is rationed, even to taxis. Drivers work until their ration is exhausted. There were 20,000 taxis in Paris before the war; now there are 8,000. As a consequence, the drivers are apt to demand more than their meter reads. One night, coming home from riding roller coasters with Viveca in a Coney Island sort of spot in Montmartre, Dennis was charged three times what the meter registered. The actor paid up but as he walked toward the hotel, the driver came running after him with his hand out. “Service, monsieur, service! S’il vous plait.”

All he wanted now was a tip!

Dennis found Paris beautiful, but not gay. “You see that she has been through something.” The people are tired, worried about their second-rate position among nations. “There is not much happiness,” says Dennis. On the streets he saw little of the much-publicized extreme styles invented by the Paris couturiéres. He’s not the sort of fellow who’d be caught dead at a fashion show or even shopping for female apparel (his coming-home present for Lillian was perfume) and the only glimpses he had of long dresses was in fancy restaurants and hotels. Only the inflation-money class, and Americans, can afford “the new look.”

american in paris . . .

In his time off, Dennis was a typical tourist, although the heat was awful, the streets almost deserted. He bought flowers for his French friends from the outdoor stalls in the Place de la Madeleine, looked over the little bookshops along the quay by the Seine. They were selling “Forever Amber” there, as “L’Ambre,” for the outrageous price of 1,000 francs ($8).

In the burning sun, “a Van Gogh sun,” he walked through the Bois de Boulogne, down the Champs Elysées, stood in the Place de la Concorde, strolled on under the great chestnut trees in the Jardin des Tuileries. The dahlias were out, and there were geraniums and yellow fuchsias. Everywhere, the colors were wonderful; delicate, warm colors—reds, blues, whites and blacks—old, black stone walls around white houses, like the paintings of Utrillo.

In the rain one day, Dennis went to the Ile de St. Louis—a little island in the Seine—to admire the Cathedral of Notre Dame. “It was so exciting, at last, to see what I’d read about. To look up at the gargoyles, for instance, and suddenly discover they were there for more than just decoration—they stretched out from the towers spitting rain-water.”

He was awed by this church, and by the many other examples of Gothic and Renaissance architecture. “To think that men could build such terrific edifices without machines or even the help of steel!”

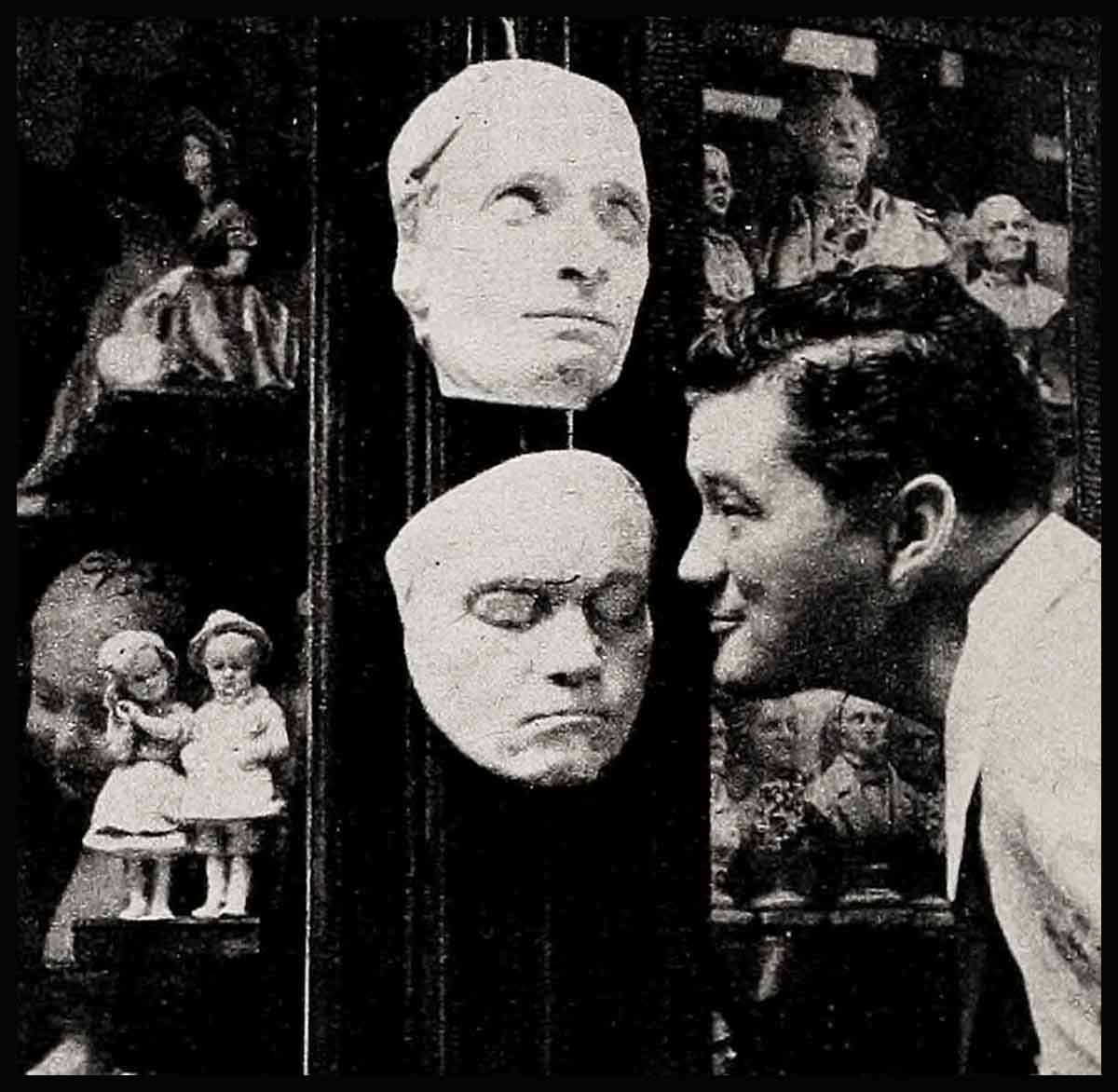

The first day’s shooting on Dennis’ picture took place in the Place des Vosges, “and old, old square—pink brickwork and pale blue shutters—built before 1600.” Dennis and Viveca spent most of the day getting in and out of a taxicab in front of the palace of Cardinal Richelieu, and great crowds gathered to watch.

Dennis spent a great many evenings with members of the French crew that worked on the picture. A good feeling developed, despite their difficulties with language, between the visiting Americans and the Frenchmen—most of the fun taking the form of not too hilarious practical jokes which were more easily understood than conversation. But Dennis was often homesick, and apparently there wasn’t anything more welcome than the sight of another American in Paris.

He saw Marlene Dietrich, Merle Oberon, a few Los Angeles businessmen; he and Paul Lukas (who was in Europe to work on another American movie) played some doubles with Marcel Bernard, the present tennis champion of France, and Toto Brugnon, one of the four great all-time French players. They played in the Bois at the Racing Club de France on those beautiful, brick-red en-tout-cas courts, surrounded by clumps of green trees. Dennis was paired with Bernard, but they lost. “I was nervous, to put it mildly.”

One night at the Café de Flore, meeting place of the literary world, he caught a glimpse of the most famous post-war Frenchman, Jean-Paul Sartre, playwright, magazine editor and founder of the philosophy called Existentialism. Their slogan: L’Etre et le neant (Being and nothing). Too deep for Dennis, he says.

It was not the season for theater or opera, but he heard a little story about one great French soprano, and it made him wish especially that he might hear her sing. The time was during the occupation. After a performance of the opera, a Nazi officer presented himself at the singer’s dressing room to pay his compliments. When the Nazi heiled Hitler in greeting, the opera star took a long wait, then made the sign of the cross!

How a citizen behaved toward the cupiers is still a matter of burning importance, Dennis found. Those who took the easy way and accepted favors have not only been politically purged, they have been purged artistically as well.

Dennis saw a good many people living in houses pockmarked by shells and rifle fire, and he saw railroad tracks with white patches in them everywhere—temporary patches made after the fighting was over. The French underground had been tremendously successful in sabotaging the railroads, but then, after the war, they had to suffer the awful problems of having almost no transportation system at all.

It was virtually impossible, for a long while, to get food distributed evenly, hence the days in 1944 and ’45 when people were reported to be burning butter to light their houses in Normandy, while in Paris, butter was selling on the black market at fantastic prices. Since then, a miraculous job has been done on the railroads which are running almost normally again.

Like all good tourists, Dennis devoted one evening to the Folies Bergére, a lavish spectacle with low comedy, torrid dances and beautiful girls clad only in plastic fig leaves. Dennis found the show less sizzling than its reputation. He was more impressed by the set designs than by the numbers and the music.

His favorite nite spot was the Monseigneur. The place seats about 75 customers, who are richly entertained by an orchestra of 38 ambulant strings—the players wandering among the tables.

Most impressive part of the trip, however, was the period of living in a small town in Normandy, and shooting on Omaha Beach, scene of the 1944 invasion. “One of the great sights of my life,” Dennis says. “It gave me a funny feeling inside.” Terrible reminders of the war are still there on the beach—mangled landing craft and German gun installations.

“When you look over the tremendous number of gun installations, made of five-foot-thick concrete walls and reinforced by pieces of iron, you wonder how our men ever, ever got through. Only a direct hit or a grenade could. knock them out. The great guns criss-crossing the beach, holding everything under their cover. In between, machine gun nests: Yet our men came in and went right up that hill! Makes you feel like you’re in church, a sacrilege if you don’t remove your hat.”

Just a few hundred yards from the beach, on the other side of the hill, he visited a small, well-kept cemetery. The hastily constructed sign stands there as it was originally written: “First American cematary in France, World War II.”

Twelve miles in from the coast, in the town of Treviers, Frenchmen like to point out a small church, partially destroyed by American shells. The clock on the steeple is intact but stopped—the hands standing at 6:30 (6:30 A.M., June 6, 1944). In the courtyard, a bronze statue of a French soldier, monument to Frenchmen killed in World War I, still stands.

peace comes to omaha beach . . .

Today, people swim among the landing wrecks on Omaha Beach, and the children play happily in the sand-filled pillboxes. The American tag has taken hold, the locals still call the spot Omaha Beach. There are even streets in Normandy named for GIs. When the troupe from Hollywood set up cameras and began shooting, crowds gathered and friendships were made despite the language barrier. Dennis met some of the F.F.I. resistance fighters, and gained a notion of their part in the invasion. Their code phrase, meaning the invasion at last is about to start, was “Nancy a le torticolis.” It means, “Nancy has a stiff neck.”

Dennis talked with a young resistance fighter who had been caught by the Germans and taken off to a concentration camp. He told of men being made to stand in the snow with no shoes, and how they worked carrying stones and of being made to put one finger on the floor and crawl round and round with the finger held in one place, pretending they were gramophones. The man, Dennis noticed, couldn’t move one of his feet.

When they returned to Paris, Dennis was more homesick than ever. Every glance at the photos of his family, which he’d stuck under the glass on his bureau at the George V, made it worse. Suddenly, one day, he turned to the phone and put in a call for home. He could hardly wait for the wonderful American sounds of his children. “Hi Dad,” they’d probably say. “What’s cookin’?” The wait was long. Finally he got through to them. His daughter, Kristin (aged 10), came on first.

“Bonjour Papa,” he heard, “comment ça va? Le chien est tombé dans la piscine, et moi, je l’ai sauvé.”

“Piscine, what’s piscine? You worry me,” he said.

“Oh Daddy,” she said, “how could you be so ignorant? Everybody knows that’s the swimming pool. Now listen! Reviens a la maison bientot—et apportes-nous beaucoup des cadeaux.”

A few hours later, he was remembering all this with a smile. Maybe, he thought, he’d better find out about cadeaux, so he searched around in his luggage for one of those books—and it’s a good thing he did, too, because he learned he had some shopping to do before he caught that plane for home.

THE END

—BY MARY MORRIS

It is a quote. MODERN SCREEN MAGAZINE JANUARY 1948