Tina Turner Happy At Last

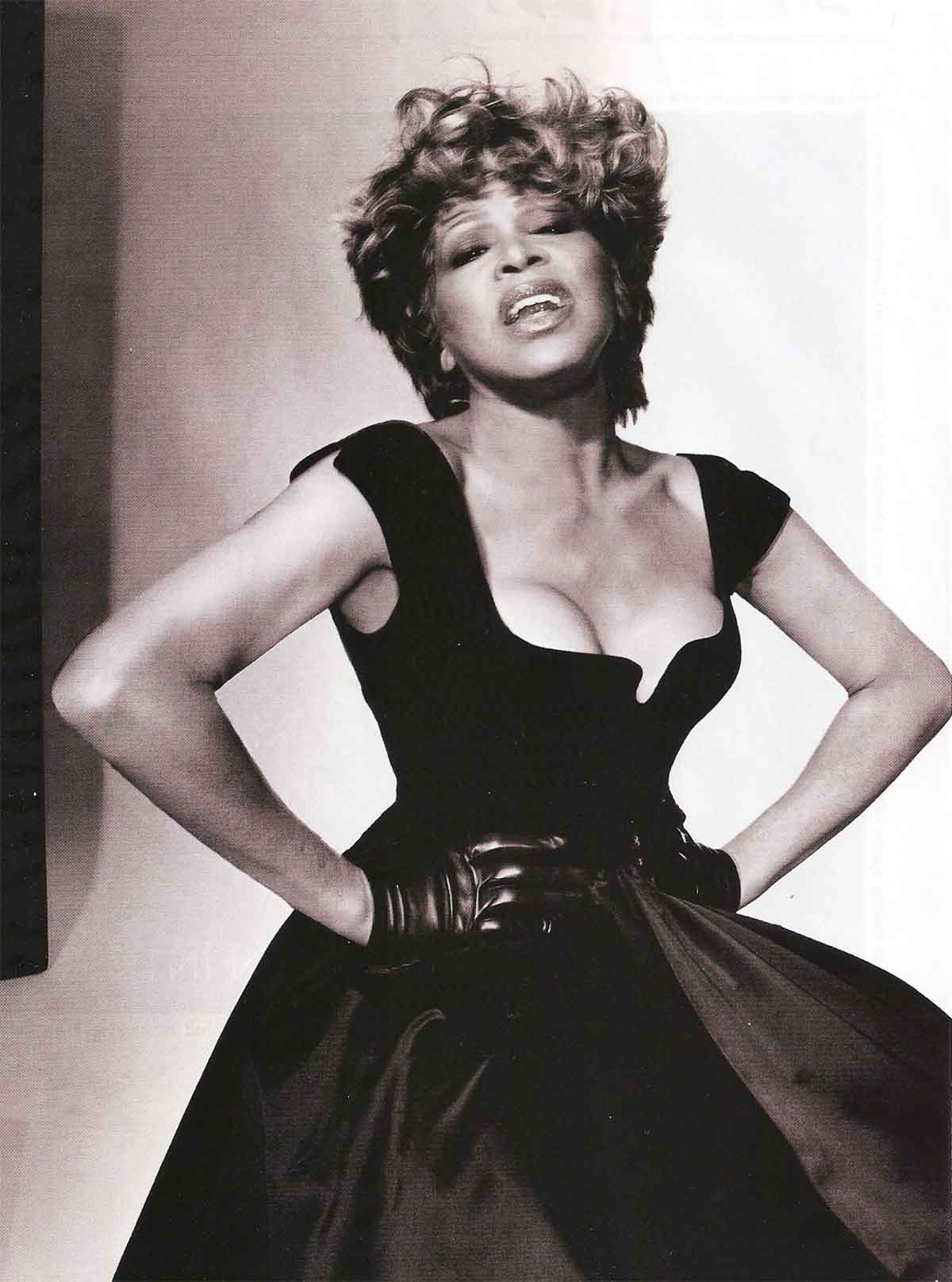

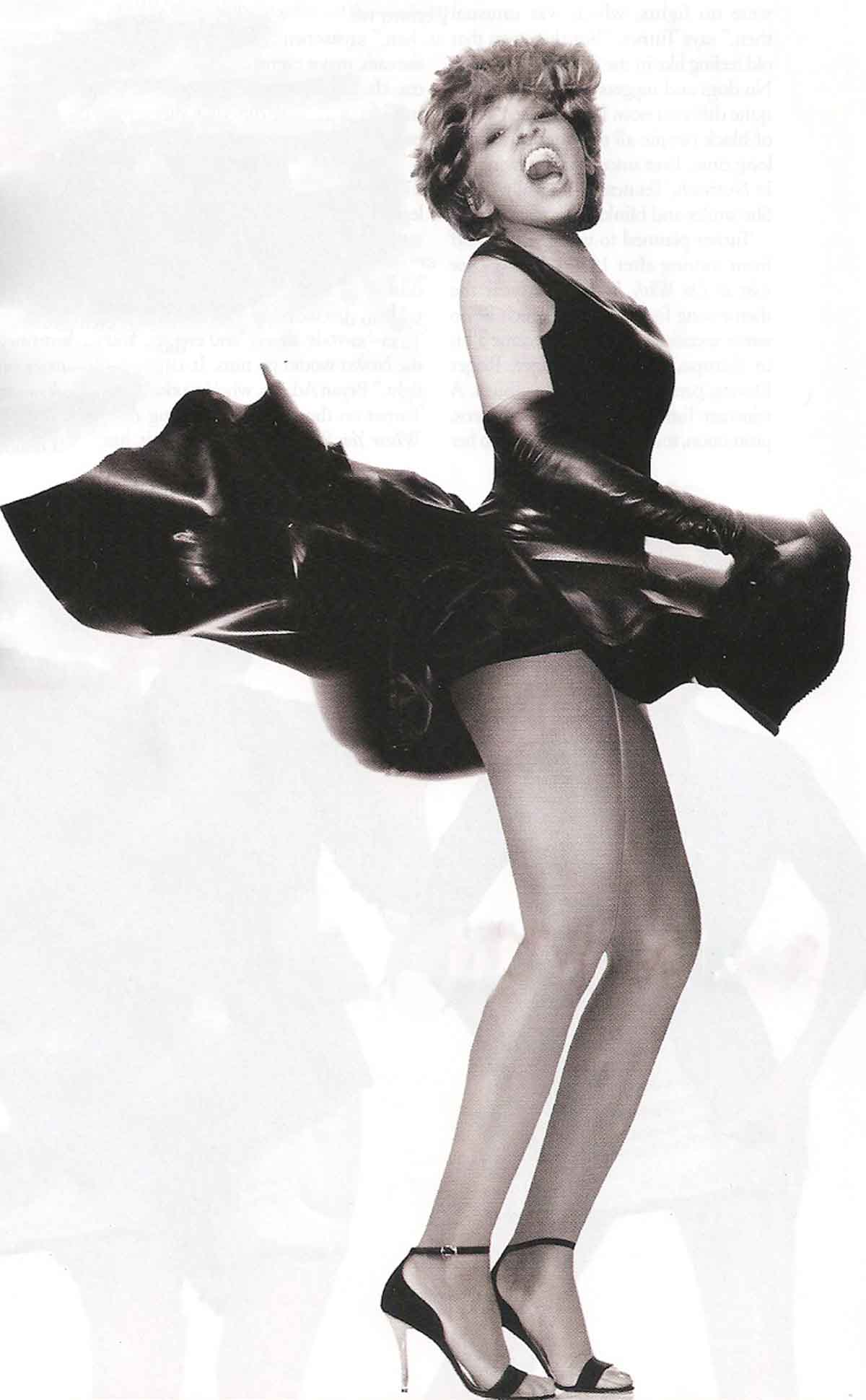

Outside, the streets are eerily empty, although it is just afternoon. The only thing moving on this day of rest in Cape Town, South Africa, is a restless autumn breeze that carries music drifting from an open window. Inside a white warehouse, deep into the beat, a woman sways her hips in a sexy figure eight, her arms snaking through the air. “Whatever you want me to do, I will do it for you . . .” She mouths the words, wets her lips, and arches her head back. An orgasmic chant.

A small audience stares, fixed on the private dancer. The photographer hungrily snaps away. The only rest she takes during the four-hour show is to change into different outfits, each one revealing a bit of something the last one didn’t. The dress she’s working now is a tight black-leather number cut down to there and up to here. A lesser woman couldn’t handle it.

Twirling, she flashes more than just a great pair of legs. A little smile. She knows you like the show. She loves that you do. Why do you think Tina Turner has been putting it on for nearly all of her fifty-seven years?

The photo session wraps and the singer slips out from under the lights and into something more comfortable—jeans and a T-shirt and a glass of Veuve Clicquot Ponsardin. (The French champagne was quickly imported from Turner’s stash at the hotel after it was discovered that cheap bubbly was going to be served at the shoot.) “Whenever I drink champagne, I either laugh or I cry,” Turner says, pulling the bottle from the ice bucket. “I get so emotional!”

Right now she can afford to laugh. Her fifth solo album, Wildest Dreams, which won’t be released until next month, already has two singles poised to take over the charts, and after years of turning down endorsement contracts, including Volkswagen and Sweet’n Low, she’s strutting hosiery for Hanes. The company is sponsoring part of Turner’s Wildest Dreams World Tour, which opened the night before at Newlands Cricket Stadium. Despite Turner’s criticisms—“The stage was blue-black! I couldn’t see anybody! Half the time I didn’t know where the dancers were entering from. I wasn’t centered in the eye for ‘Goldeneye.’ It was a nightmare!”—she gave South Africans their ’rands worth. “Sixteen years ago when I was here, I did quite well. I drew a mixed crowd and there were no fights, which was unusual then,” says Turner. “But there was that old feeling like in the South, in America: No dogs and niggers allowed. Well, it’s quite different now. I haven’t seen a race of black people all together in a long, long time. Ever since I was growing up in Nutbush, Tennessee. It’s really nice.” She smiles and blinks back tears.

Turner planned to take five years off from touring after 1993’s What’s Love Got to Do With It? but last year the theme song for Goldeneye (which Bono wrote specifically for Tina) became a hit in Europe, and her manager, Roger Davies, pressed her to do an album. A reluctant Turner knew the drill—“videos, promotion, tour. . . .” Three years into her vacation, she was back in the studio. “I’ve always wanted to fill stadiums, and if you get to the stage where you fill stadiums, what are you going to stay at home for?”

And why stay at home when you could be duetting with the likes of Antonio Banderas, who sings backup on Dreams’ European title track; or Sting, who can be heard on “On Silent Wings.” Like a siren’s song, Turner’s genius is such that when she calls, major talents drop everything. “I couldn’t say no,” says Sting. ”I went by the studio that same night, did it, and had a ball! Who could refuse Tina Turner?”

From her beginnings with Ike Turner, Tina’s collaborations with men have been legendary. She taught Mick Jagger how to dance and showed Mel Gibson a thing or two about attitude. “She used to come down to the set wearing the chain-mail negligee,” says her Mad Max Beyond Thunderdome co-star, “and everybody in the crowd would go nuts. It was a wild sight.” Bryan Adams, who’d worked with Turner on the Grammy-winning Back Where You Started, was, as he puts it, just a young “football hooligan” when they had their first encounter at the Commodore Ballroom in Vancouver, British Columbia. Turner was scratching out a living on the club circuit after walking out on Ike. (His abusiveness and her survival were chronicled in the 1993 film What’s Love Got to Do With It?) “This was way before her comeback,” Adams recalls. “I’d go see her and be dancing on the table by the end of the night. Afterwards, I thought, Fuck it, I’m gonna meet her because she blows my mind. I snuck backstage.” Turner was extremely ill and being helped out the back door. “I remember thinking, My God, she just sang the most brilliant set and she had the flu! And from that point on she was my standard for performers.”

In 1979, Roger Davies went to see Turner live for the first time at the Fairmont Hotel in San Francisco. “I was skeptical,” admits Davies, a strapping blond Australian who, at the time, managed Olivia Newton-John. “It was in the Venetian room with chandeliers and Tina came on wearing all these sequins, with a band in tuxedos, and I went, Oh my God. You know, people were sitting there having dinner. But by the end of the show she had the whole crowd on their feet. Her energy blew me away.”

And Turner was, as Davies puts it, “hungry. She said, ‘I want to get out of here and play rock venues.’ ” For the second time in her life, Turner put her career in a man’s hands. “Trying to get her a record deal was difficult because people in the industry were scared of Ike,” says Davies. “People weren’t aware they were divorced. We had to go to England to get a break.” Tina kept to the club circuit, while Davies went to work pulling in every favor owed him to put together what would become her first solo album. He laughs, as if to say, Those were the days. “When I first got in volved, she was in debt, and she had this amazing knack of going into shops and saying, ’Excuse me, I’ll take that dress’—they all knew who she was and just call my manager and he’ll send you a check.’ And she’d leave town! I’d get these phone calls and they’d say, ‘It’s Valentino, Tina just picked up a few dresses,’ and I’d say, ‘Fine.’ And they’d go, ‘$16,000.’ I’d ring her up and she’d say, ‘Well, I’ll make the money this week!’ All her life, Tina spent money before she made it.” Imagine Davies’s relief when Private Dancer sold over ten million copies.

“Let’s freshen up our glasses a bit,” says Turner, a gracious host even in her makeshift dressing room. ”I love champagne. I love it so much so that I collect glasses and I need a special glass.” Special being a fresh flute for every refill. “When a glass looks like that,” she says, wrinkling her nose at a smudged crystal specimen, “I’m ready for another one. I have more glasses in my house than I have pots and pans!”

When not on the road, Turner “putzes” around her house and garden in Gstaad, Switzerland, where she lives with her lover of ten years, Erwin Bach. The E.M.I. record-company executive is sixteen years younger than Turner. “Erwin says to me, ’If you ever took on someone your age, it wouldn’t last. Sometimes it gets hard for me!” When it comes to the opposite sex, Turner is drawn to “a good person from the soul, that’s number one. I like them cute, but not too pretty. . . .” And then she gets right down to it: “I watch hands and feet. More than anything else is a very deep masculinity. I cannot live with a weak man.

“I was, excuse the expression, pissed when the thing first came out about my life, and Ike, and everybody said, ‘You were a victim.’ And I said, ‘I was not a victim!’ I was totally in control of every single thing I was doing. I knew where I was! Do you understand?” She shakes her head, leans back, and runs a hand through her hair. Looking up at the ceiling she continues. “I cared about Ike. I was trying to help him. I had made a promise. But people still want to say at you were a victim of. There two ways of looking at that. Being a victim and being in control of being a victim. That’s what I’m trying to tell you I knew precisely what I was doing.

“I was in love with Ike once. And then I was not in love with him. But I was still trying to help a being that I cared about right to the very end. That’s me. Some people call it a weakness. I think it’s a strength.” (According to Davies, Ike tried to contact Tina after the success of Private Dancer: “He turned up at a show and freaked her out in L.A. and we got a few letters. But he’s remarried and making a comeback. So we haven’t heard from him for a long time.”)

As she sings in “Whatever You Want Me to Do” from the new album: “Time takes, but love heals.” The words testify to where she is now, but even after achieving independent success there were pieces of her history still too painful to revisit. ”She could have had a great acting career,” says George Miller, who directed Turner in Beyond Thunderdome. “Not long after the film, Steven Spielberg Purple, and to my shock, Tina turned it down. I called her at Steven’s behest and said, ‘You’re crazy! This is a great role!’ And she said, ‘Look, in order to play it, I have to dredge up all that was negative in my life. I don’t want to go back to that place.’ I admired her conviction. I know how much she wanted to act and I know how good she could have been. But to be so certain that she didn’t want to do something which under normal circumstances would be so seductive . . . I was really impressed.”

Turner is sent scripts and offered roles all the time, most of them as prostitutes. “A lot of people use those kinds of parts just to get in. I don’t have to because I have my career,” she says. “I like really good, clean, meaningful movies. I like the earlier films Sigourney Weaver did. Action things. And Thelma & Louise would have been a wonderful part for me and somebody.” She drinks from her glass and a little burp escapes her. “Excuse me! Bubbles!”

There is a knock on the door. Davies has been patiently waiting to take Tina back to her hotel. But now it’s late and he’s concerned that she hasn’t eaten yet. “Go away!” Turner yells. “We’re not done talking.” She winks and lowers her voice conspiratorially. “We’re not leaving until we finish the champagne. We don’t want to waste it!”

Much later in the evening, Turner’s black rented Mercedes finally pulls into the kitchen loading area of the Cape Sun Hotel. Turner steps from the car and, surrounded by Davies and several other men, is hustled through a back door, up a steep flight of stairs, and into an elevator. On the thirty-third floor her chef has already begun cooking the vegetables-and-pasta dish that has become a tour staple. While waiting, Turner signs CDs and sorts through boxes of T-shirt samples. She’s full of energy, despite the fact that she has hardly slept since arriving in Cape Town three days ago. Says Davies, who looks exhausted, “We’re doing this grueling tour for eighteen months. I doubt that acts twenty years younger could keep up this pace.”

Turner must be drinking Youth-Dew. After a recent physical, her doctor, according to Turner, pronounced that she had “organs of a woman ten years younger. The doctors were cheering.” Turner is convinced it’s because she grew up in the South, eating vegetables straight from the garden. “My body is strong!” she says, proudly poking it. “I never smoked. I didn’t break my body.” Beyond that, she is living proof of mind over matter. ”Here’s someone who, in every way, is highly evolved,” says Miller. “Spiritually, in terms of her pragmatic wisdom of the world, her childlike capacity for joy—all of that. I mean that life force is just fantastic.” The director’s first meeting with Turner haunts him. “I remember being ushered into her house and hearing this beautiful chanting, several rooms away. She was doing her meditation. It was very powerful.”

“I like how I’ve changed my life, practicing Buddhism,” Turner says. She’s one of the few people who can get away with the phrase, ”My wildest dream was to become one with myself and enjoy being alone. Just enjoying life and getting to a place of being.” (“She’s much more spiritually balanced than I am,” says Davies. “I’d love to meditate, but I’m always on the phone.”)

Miller points out that Tina got to this place the hard way, as opposed to “something glibly learned from a self-help book.” Turner concurs: “When you’re going through the learning process, you feel like, Oh, what an awful life! But when you get through it, you think, Damn it! I did pretty good! Nobody did it but me. I surrounded myself with people that helped me get there and I got there.”

And she takes care of those she loves, including her two sons. Sometimes she wonders if spreading the wealth has kept I was not in love a few from growing up. “I’ve got children sitting there just waiting for mother to do it. But if I was not able to, I know where they would be. Understand? That’s what I use money for. It comes into me and I pass it right through to family and to friends. I’m not used. I raise a little hell now and then, because there can be a dependence that they don’t even try to get on their feet and help themselves. But I do it out of joy. I’m happy that I can.”

Two nights later, on an outdoor stage in Durban, a rainstorm started before Tina Turner finished her first song. She was drenched. The dancers were drenched. And Davies was scared to death they’d all be electrocuted. But Tina kept on. “Two hours in the rain,” reports Davies. “And because she was working so hard the audience got into it even more—they thought it was great. They turned it into a party.”

What else? If anyone can turn a bad situation completely around, it’s the queen of karma. “I believe that I’m as happy as I’ll ever be,” Turner says. “I never felt sorry for myself. Once you start the self-pity, you’re dead—you’re in the box. I didn’t allow myself to go in that friggin’ box. That’s the message. Don’t accept it. Keep going.”

It is a quote. ELLE MAGAZINE 1996

No Comments