Why The “Rebel” Craze Is Here To Stay?—From Brando To Presley

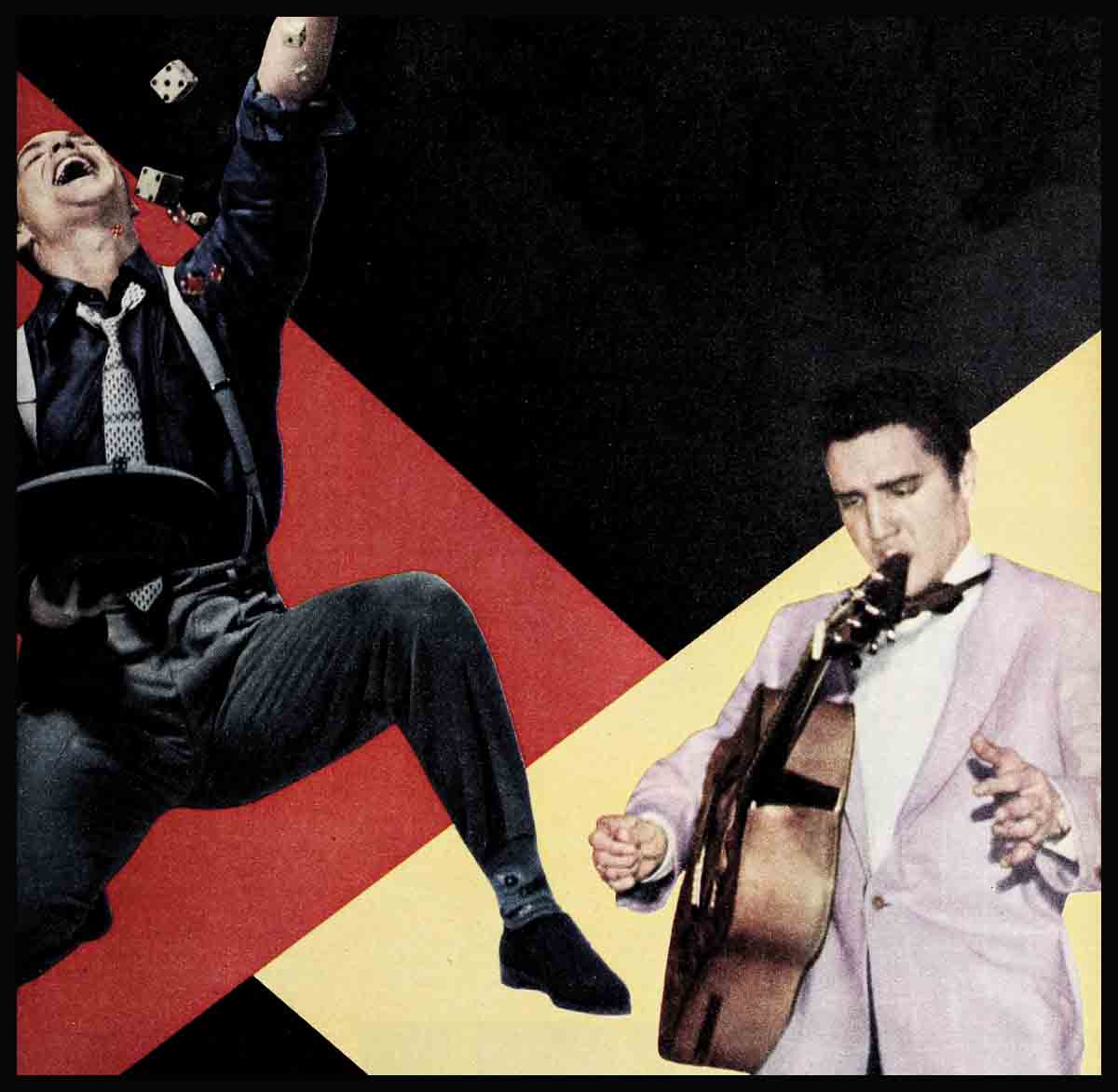

Back in 1947, a brilliantly talented young actor named Marlon Brando, appearing in the Broadway production of “A Streetcar Named Desire,” snarled and slouched his way to fame, stardom and riches in the role of Stanley Kowalski—and inaugurated a whole new “rebel” school of acting and actors. Today, this now-famous school stretches from Broadway to Hollywood and back again. Hollywood’s top-name stars have flocked to New York to study at the school which is credited with producing the most famous of the “rebel” actors. The Actors’ Studio, though Brando did not study there. And graduates of The Actors’ Studio have, in turn, been carefully, observed and screened for anyone even vaguely in the image of Brando or the late James Dean. Some of the roles Sal Mineo has portrayed—notably in “Rebel Without a Cause” and “Crime in the Streets” for the screen, as well as similar roles on TV—make the young New Yorker another prominent member of the group that appeals to the rebel instinct in young audiences. And, of course, the latest to wear the crown is that undisputed king of rock ’n’ roll, Elvis Presley, who is scheduled to make his first movie for 20th Century-Fox this year. People who have seen his screen test—professionals all—are already climbing aboard his bandwagon and predicting Elvis will be “another Jimmy Dean.”

Whether or not Elvis Presley will be another Jimmy Dean is open to question, but there is no doubt at all that he has given a whole new impetus to the rebel “craze” and given the older generation a whole new set of worries. The question that anxious parents are pondering is: “Why do our teenagers worship young stars who, in their movie roles at least, represent youth—and human nature—at its worst?”

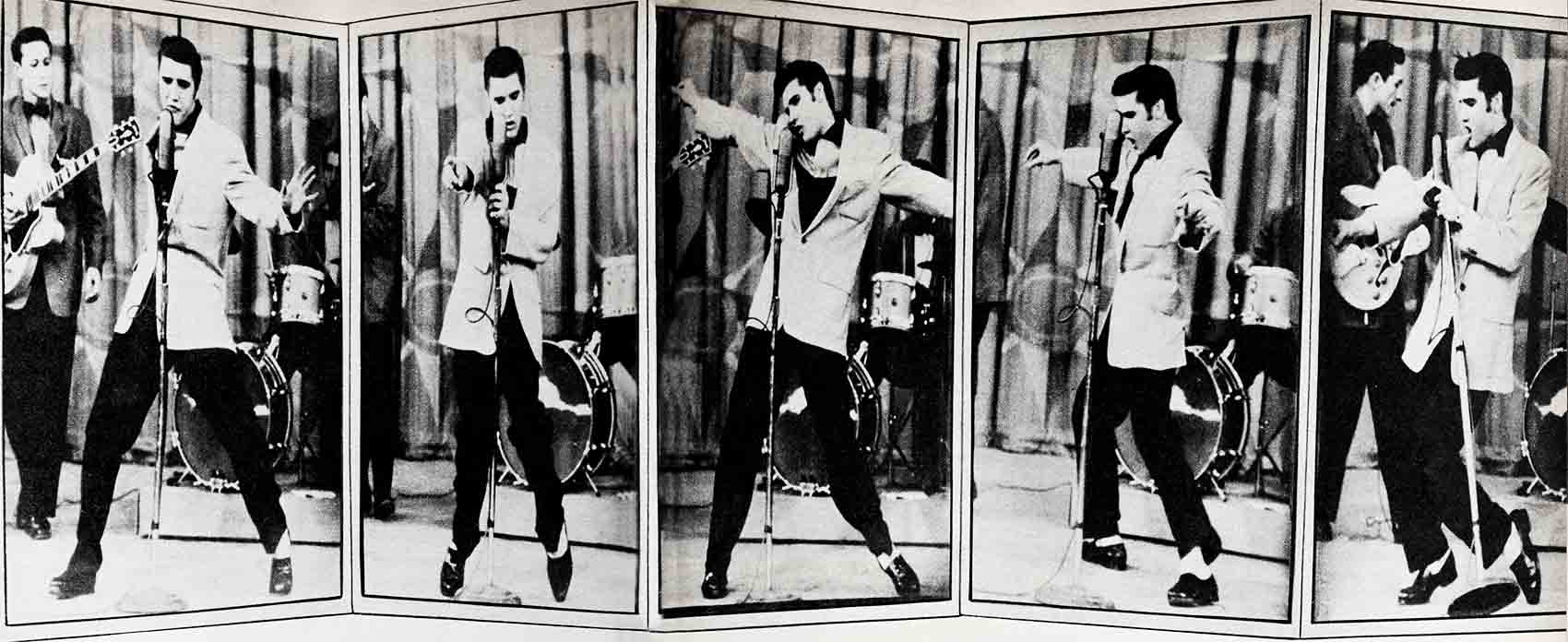

One young fan of Elvis Presley came up with part of the answer when she wrote to a newspaper columnist: “First and foremost, Elvis is like one of us. . . . He is a little frustrated, unsure, impulsive. . . . He is no child, yet he is still not an adult. . . . He’s sure about some things but confused about others, just as we are. To me, Elvis represents everything that’s uninhibited and un- conventional. He’s an outlet—an escape for our feelings. He demonstrates a wild, free emotion that we teenagers would like to express but can’t. . . .”

And the thousands of letters addressed to Jimmy Dean that still pour into the mail department of Warner Brothers’ studio have much the same thing to say: “You,” the fans write, as though he were still alive, “are one of us. When I watched you in ‘East of Eden’ and ‘Rebel Without a Cause’ I was seeing myself. . . .”

Marlon Brando got the same kind of response from teenagers. when he made “The Wild One.” One line of dialogue that was quoted and re-quoted in towns and cities and villages was his reply to the question, “Look, kid, what are you rebelling against?” Snarled Brando, “What have you got?”

The words found an echo in thou- sands of blindly rebellious teen-age hearts, just as did Jimmy Dean’s bewildered “Pa—why don’t you love me, Pa?” cry as he threw his arms about his father in one of the most poignant moments of “Eden.” Sal Mineo struck a similarly responsive chord in “Crime in the Streets.” Wanting love so desperately, feeling so guilty about hurting his parents, he was still totally unable to communicate his needs or understand theirs. And he turned away rom the father who was trying to help him with a confused, angry shout that has probably been heard in every house in which there is a teen-age son or daughter: “Aw, lemme alone, can’t you? Just lemme alone.”

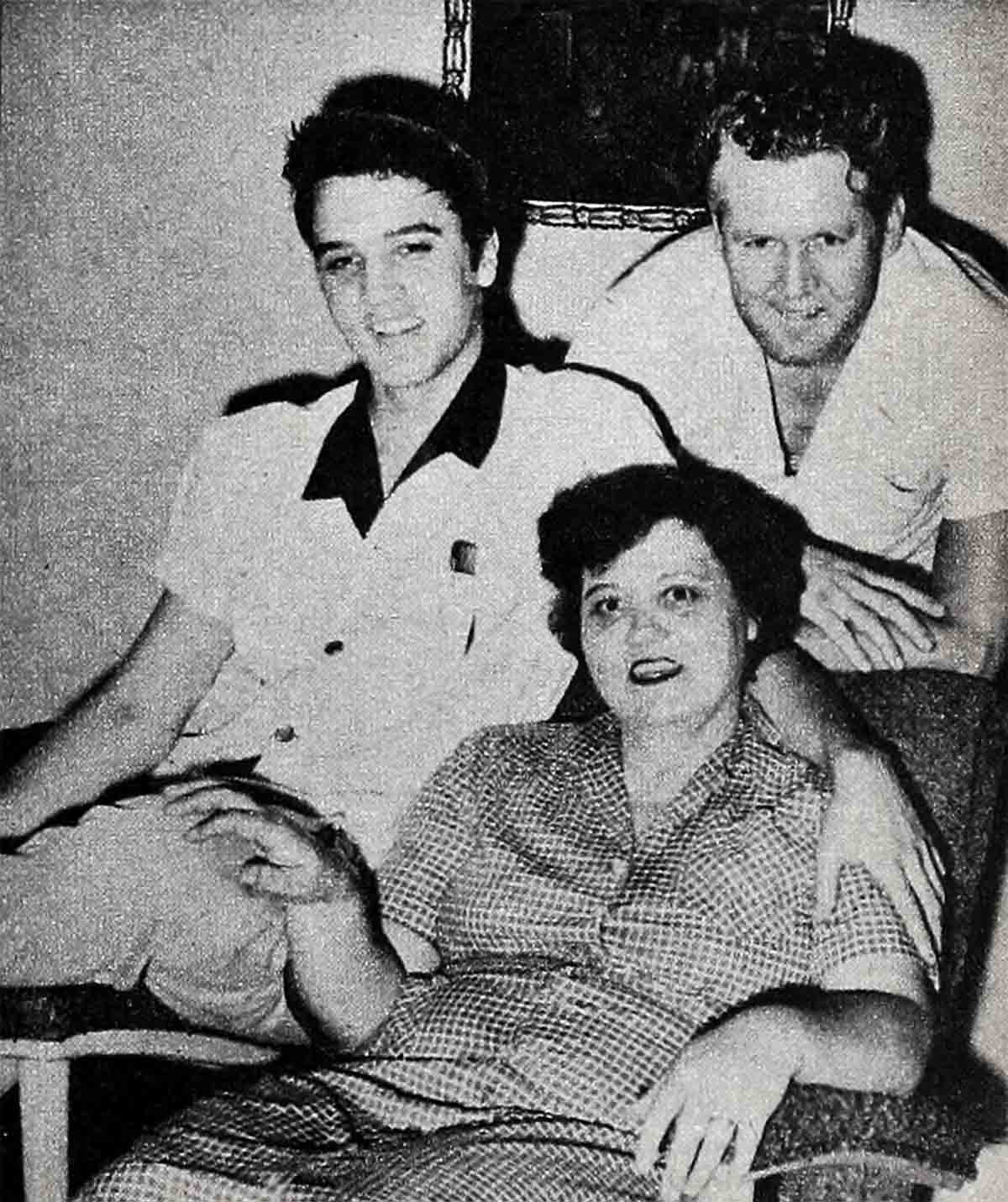

He lives with his parents when he’s in the East, raves about his mother’s cooking, says of his father, “He’s the kind of father I hope to be some day”

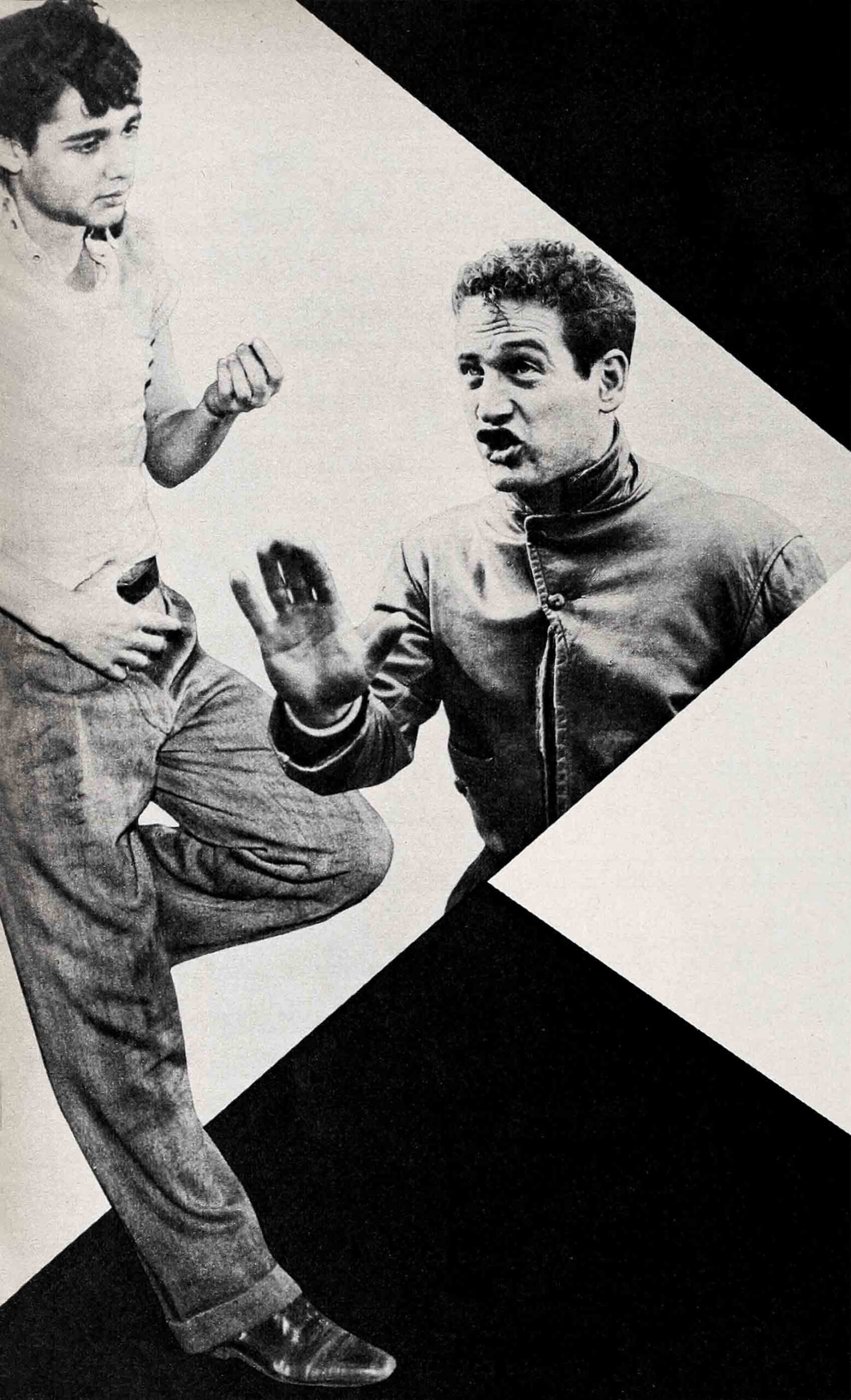

In “Somebody Up There Likes Me” Paul Newman, fighting the world with his fists in the role of Rocky Graziano, again gave teenagers someone with whom to identify. As a mixed-up juvenile delinquent, Rocky felt the world owed him a living and that he had a right to steal what he couldn’t get otherwise. Nobody loved him or understood him, so why should anyone expect him to love the world or anyone in it?

He wears T-shirts und shot to fame portraying tough-guy Rotky Grazano, but he’s a soft-spoken college grad whose life is work, wife, kids

From Brando to Presley, over a span of ten years, the demand for this type of actor has steadily grown, until today Presley represents the new type of screen lover. As Cary Grant once remarked thoughtfully in an interview that looked back over his own suave screen life, “Apparently, the way to get a girl to fall in love with you these days is to be insufferably rude, neglect to shave for days at a time, show up for a date wearing blue jeans and a leather jacket and take the young lady for a ride on the back of your motorcycle.”

First thing he did with his money was to buy his mother a car, parents a new home. Doesn’t drink or smoke, his big vice is dropping coins in jukeboxes

This trend has not only created a new kind of hero, it has made a legend of James Dean, it has provided Elvis Presley with enough money to buy a car for every day in the week, and it has apparently made a memory of the wholesome, clean-cut, well-scrubbed, all-American boy who respected his parents, went to church on Sunday and stood up when an older person entered the room.

What brought about the change? And does this new “heel worship”—this worship of all that is rebellious, unconventional, rude, even brutal—mean that this generation of teenagers is any worse than the teenagers of ten or twenty years ago?

The answer from one expert, psychoanalyst Robert Lindner, author of “Rebel Without a Cause,” is a flat and reassuring “Absolutely not.”

According to Doctor Lindner the need of the young to rebel is so fundamental as to be called an instinct. He goes on to say, in his book “Must You Conform?” that any scientist would be amazed to find it necessary to defend this instinct, any more than we should need to defend other instincts—such as the instincts to eat when we are hungry or to want to sleep when we are tired.

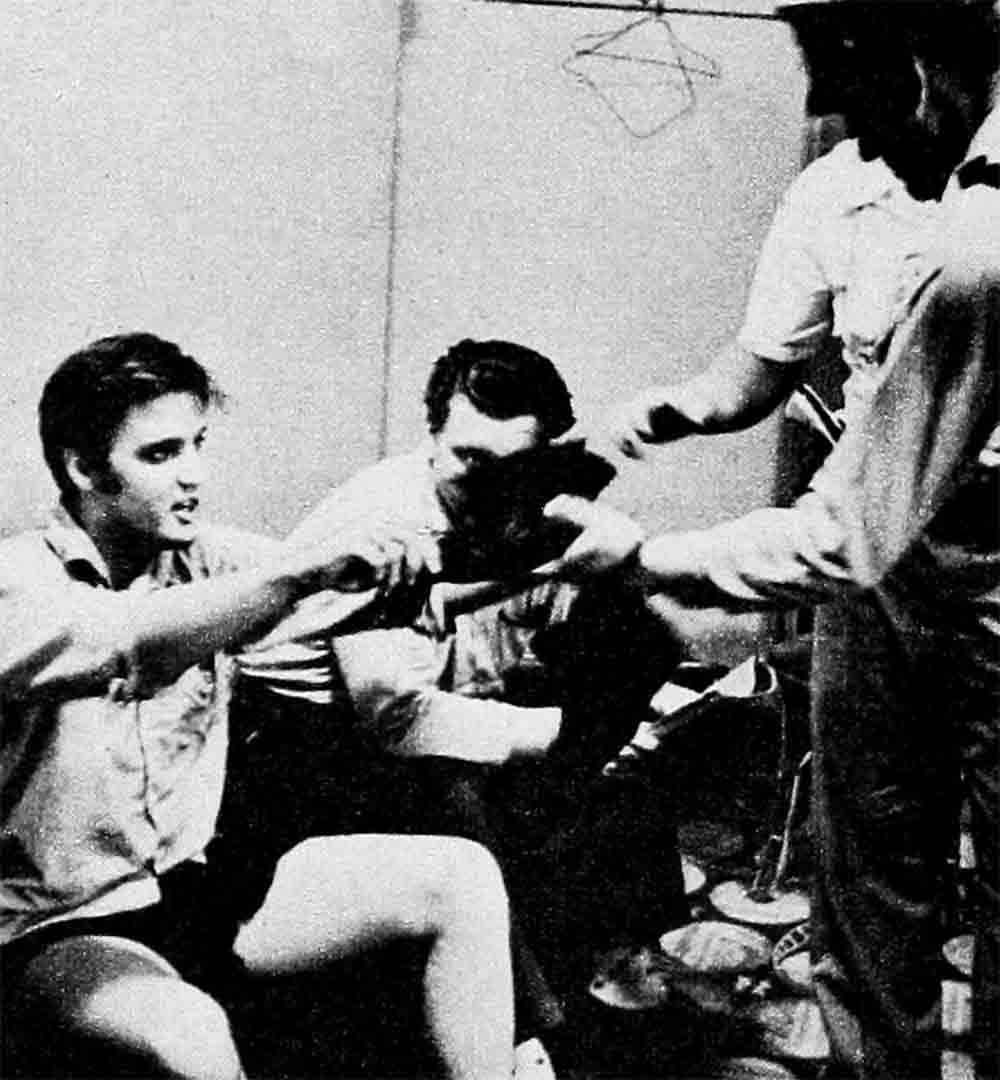

There are two ways in which this instinct, this need to rebel, is carried out by teenagers today. One is to act out their hostilities by acts of violence and delinquency; the other is to merge, herd-like, with a group and be directed by a group mind. This would certainly explain the hysterical frenzy of the crowds that greet Elvis Presley at every performance—a mass hysteria that reaches its peak by ripping off his clothes and, when he was in Miami Beach, Florida, for instance, by actually reaching up and pulling him bodily off the stage. As his young fan wrote in her letter, Presley is acting out the hostilities and the confusions which these teenagers all feel, and so he masterminds, so to speak, their mass rebellions, acts them out on a stage as they would like to do. Thus, he becomes their hero.

That Presley feels and is aware of the power this gives him is shown in one comment he made to an interviewer. Asked whether he minded the unfavorable publicity and critical remarks he often receives in the nation’s press, Elvis said gently, “Oh, I don’t mind. After all, they criticized Jesus Christ, too, didn’t they?’

Another secret of Presley’s fantastic success is the fact that the older generation is so violently opposed to him. The more they criticize him, the more his contemporaries are for him, especially since the criticism can’t hurt him. In other words, he can defy the authority of which they are the victims, and so they cheer him on. Despite all criticism, the demand—and the price—for his services goes on skyrocketing.

But the admirers of this whole school of young “rebels” overlook one fact: While Presley, Brando, Mineo, Dean and the others are idolized for appearing to fight against society and against authority, in their private lives every one of these young men is a complete conformist. They are hardworking, church-going and home-loving, ambitious for fame and success. In other words, in their personal lives the rebellious feelings which they share with all young people have taken the perfectly acceptable and even admirable form of working hard in order to become the masters rather than the victims of their environment. It is unlikely that any of them would ever be found in a screaming mob of young people, working themselves into a frenzy while reaching for a torn scrap of an idol’s clothing. Each one of these young men, in fact, has an amazingly deep sense of responsibility toward his family and friends, and their rude or shocking behavior is reserved strictly for the occasions when they are in front of a camera or a microphone.

In fact, the wife of the owner of the Crown Electric Company, where Elvis was employed after graduating from high school, says of him, “When I first saw him, with that wild hair and those sideburns, I wouldn’t even have given him an interview, much less a job, if a friend hadn’t warned me not to let his appearance fool me. Within a week, his good manners, his willingness—like his singing in the stock room—had won our hearts. Like everyone else, we loved that boy.” And now David Weisbart, famous as the producer of “Rebel Without a Cause,” is producing Presley’s first film, “Love Me Tender,” for 20th Century-Fox.

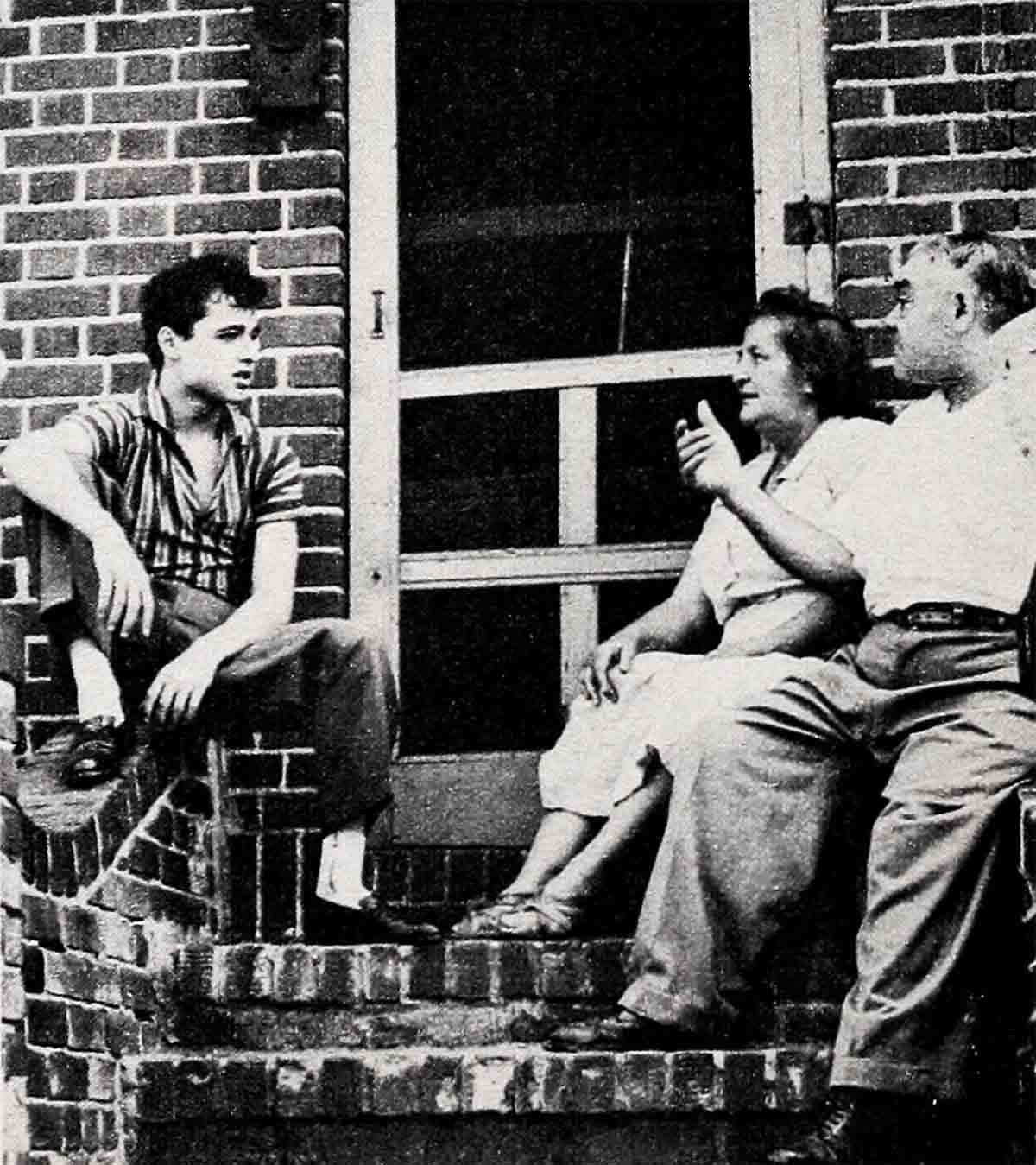

With the first important money he earned after fame struck, Elvis bought his mother a car and bought a new home for the family. He vowed they’d never want for anything again. He made his first radio appearances at night, after a full day’s work. His other evening hours were spent practicing, trying out new songs, contacting people who might be able to help him. He is a devoted son, and of his younger days his mother says, “He’d be content just to sit in front of the radio or play the phonograph, thumbing on the guitar we’d bought him, trying to learn the songs he heard. I never cared how many kids came over to the house, nor how much noise they made, as long as I knew they were all right—that they weren’t getting hurt or into any bad mischief.”

Young Sal Mineo comes from the same kind of closely knit, devoted family, and Sal’s mother, too, was strict in her insistence on knowing where her children were at all times and what they were doing. Like Presley’s mother, she encouraged Sal in his ambition to be an actor. Though his family was far from wealthy, there was money available for Sal’s dancing, voice and dramatic lessons. His family was never too busy to be interested in what he was doing and thinking, and that might offer some explanation as to why, in these young people, the instinct to rebel drove them on to fame and fortune.

Mr. Mineo, who is a carpenter and coffin-maker by trade, is very much the head of the house and of the family, and he refuses to accept any money from his famous son, even though Sal’s earnings are larger than his.

“That’s the kind of father I want to be some day,” Sal says, “and I hope my kids will look up to me the way we look up to him. Man, when he says something, he means it!”

As for vices, Sal’s only noticeable one is a healthy liking for second helpings of dessert. These he can put away with no appreciable effect on his slight but well-put-together frame. His favorite drink is milk, or Seven-Up with a lump of vanilla ice cream added to it.

Like some of the characters he portrays on the screen, Sal was raised in the shadow of the “El” in a crowded, teeming Bronx neighborhood. He shined shoes and sold newspapers for extra spending money, but he never had any time to waste hanging out with the gang on the street corner. He was nine years old when he had his first small part in the Broadway production of “The King and I,” playing one of the king’s children, and he’s been working and rehearsing every spare minute since. When he’s in the East for TV appearances or resting between movies, he lives at home with his parents, his brothers and sister. He never misses a Sunday mass at the neighborhood’s Catholic church. Although he has proved his ability to hold his own in the street fights all boys get into when they’re growing up, he is a soft-spoken, beautifully mannered young boy who stands when an older person enters the room and always gets to the car door ahead of his date to hold it open for her.

Paul Newman, who did such an outstanding job portraying Rocky Graziano in “Somebody Up There Likes Me,” is a college graduate who tried going into his father’s sporting-goods business before deciding on an acting career instead. He attended the Yale School of Drama, went into summer stock, played the lead in “The Desperate Hours” on Broadway and was then discovered and signed by Hollywood and Warner Brothers. The only signs of a “rebel” about Paul, a married man with two young children, are his liking for T-shirts and his refusal to give interviews on his personal life or to permit anyone to photograph him with his family at home. He lives on Long Island with his wife and children when he’s not making pictures. They never accompany him to Hollywood because “It’s important for kids to belong,” he says, “to be a part of a community.”

Off screen Paul still looks like a young college boy, appearing to be much younger than his thirty-one years. He doesn’t drink or smoke. He’s restless, tense and so eager to be pushing on to something else that he gives the impression of moving even when he’s standing still. He’s tolerant of almost any shortcoming except laziness. If you want to do something, according to Paul Newman, why, you just go ahead and do it, and there are few things you can’t achieve by plain hard work.

Paul’s first movie role in “The Silver Chalice” is something he prefers to forget. For a while after that it began to seem as though his remarkable resemblance to Marlon Brando would mean the end of his movie career. His role in “Somebody Up There Likes Me” also brought forth a few comments about the similarity between Brando’s acting and Paul’s, but there is so much about this promising newcomer which isn’t at all reminiscent of Brando that the comparison cannot really hurt him. Nor is it apt to last through another picture.

Speaking of that, Paul said, “I happen to be a great admirer of Brando’s, and if people want to compare me with him, it’s all right with me. But I think that all this ‘comparison’ stuff isa form of laziness. I mean, a writer can’t figure out how ‘to say what somebody has, so he just says, ‘He’s another Brando’ or ‘He’s another Jimmy Dean.’ Actually, no one’s another anything. Each of us has something peculiarly our own—and I think that’s what a writer ought to try to find out, and write about.”

What Paul Newman has that’s peculiarly his own is a sort of facial anonymity which will allow him to play a wider range of characters than most actors can handle. He doesn’t look like an actor. He could be the boy next door, the prosperous young businessman down the street, the kid home from college, the bully on the street corner, or the young Army officer, which last he portrays in his next movie, “The Rack.” Still studying at Actors Studio when he’s in New York, Paul is an outwardly gentle, soft-spoken young man, an inwardly intense, restless one. One of the waitresses in the little restaurant near the Studio said admiringly of him to a friend, “I just love that man. I’ve seen him coming in here from the time when he wasn’t anybody until now when he’s really famous, and he hasn’t changed a bit.”

Told about that, Paul smiled and said, “Well, if she means I haven’t gotten a new set of manners, she’s right. But, of course, I have changed. There’d be something wrong with me if I hadn’t. It’s just that I haven’t changed in any way that shows, and I don’t imagine I will.”

He still speaks in a soft voice, goes to small, out-of-the-way, inexpensive restaurants, fixes his own car and is scrupulously punctual for all appointments. Of the rebellious young hoodlum he portrays on the screen, Paul says, “He was just mixed up. From the time Rocky knew that somebody really liked him and cared about what happened to him, he tried to straighten himself out.”

Marlon Brando, who disliked his role in “The Wild One” and protested against playing that vicious a character, is one of the gentlest and kindest people in the world. It actually pains him to see anyone suffer, and he will go miles out of his way to help others. He tried several times to get close to Jimmy Dean, to talk to him, to try to help Dean understand himself a little better. Brando also held out a friendly hand to Mario Lanza when Lanza was fighting to make a comeback.

Like the other “rebels,” Brando was close to his family, adored his mother and has a warm and close relationship with his father, who is also his business manager. He is devoted and big-brotherly to his lovely sister, Jocelyn. While he got into trouble at school plenty of times and has shocked a good many people since then, Brando’s rebellion and shocking behavior —when it is shocking—is generally directed at people who are either rude or stupid or both. He avoids—along with interviews on his personal life—big parties, celebrity hunters and girls who feel a silence is something to be filled with talk, any talk. He asks fabulous sums of money for any and all professional appearances, but will work for nothing if his turn on a stage will help some down-and-out actor friend. His “vices” are a love of classical music, good books and cats. He doesn’t drink, and the only time he stays up all night is when he has found someone exciting to talk to.

Jimmy Dean, too, rebelled against many forms of conforming, but this was mostly in connection with himself as a movie star. He hated that part of himself, and of success. He wanted to be an actor, yes; he wanted to be a great actor. But he didn’t want to be stared at like a lion in the zoo or questioned about his taste in ties or women. His rebellion, too, took the form of competing, of determining to be better than anyone else at everything.

It is normal for youth to rebel, and it is normal for the ones who lack the courage to rebel themselves to cheer on the ones who do break the mold, those who appear to defy convention—and get away with it. But while they’re cheering on their rebel heroes it might be well for today’s teenagers to give a little thought to the private lives of these young men. They’re rebels, too—all of them. Rebels against failure, against laziness, against staying in the rut or the place or the job you happened to be born into. But in-stead of rebelling on street corners, where it doesn’t do any good, they rebelled by working nights as well as days, by refusing to accept the idea that they couldn’t be better than they were. The whole secret of their success can be summed up by something Jimmy Dean was fond of saying:

“When you fail, you try again, that’s all. You never let them lick you—never.”

Maybe, when the hysteria of the rebel craze dies down, there will be time to hear—and heed—words like those.

THE END

YOU’LL LOVE: Sal Mineo in “Giant”; Marlon Brando in “The Teahouse of the August Moon.”

—BY LAURA LANE

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE NOVEMBER 1956